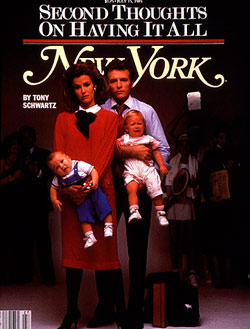

From the July 15, 1985 issue of New York Magazine.

Twice during the past month, colleagues approached 38-year-old Rebecca Murray* and volunteered identical assessments of her life: “You are the woman who has everything,” they told her. The notion staggered Rebecca. “I have never, ever thought of myself that way,” she says. But it’s not hard to see what her co-workers had in mind.

For the past eighteen years, Rebecca has been married to the same man—Robert, now 42—and their marriage remains strong. Their five-year-old daughter is pretty and bright. Rebecca works as a records manager for a large financial institution and earns $40,000 a year—with plenty of potential to move up. Robert makes $43,000 a year as the business manager for a publishing house. Free-lance writing brings in another $5,000 a year. He is a novelist, and although his advances have been small so far, that could change with a single success. The Murrays’ combined income of nearly $90,000 is more than four times the salary earned last year by Robert’s father, a construction supervisor in Florida, and a lot of money by nearly any standard. What’s more, they pay just $450 a month for a rent-stabilized apartment on a pretty street on the Upper West Side. Among other things, they can afford the $8,500 a year it costs to send their daughter to a private day-care center where the ratio of children to teachers is four to one.

But none of this compensates for what Rebecca feels is missing in her life. “Time,” she says. “I don’t have enough time for my child, I don’t have enough time for myself, and I never have enough time for my husband. He gets whatever I have left at the end of each day, and usually that’s nothing. I don’t want to leave my child in the mornings—and she doesn’t want me to go. I’m fine once I get to work, but once the day starts winding down, I get very anxious to rush to my kid. I can’t wait, I want to be there in a second, and sometimes the subway is interminable. At the same time, I’m aware that I’m looking at an evening that’s not going to be relaxing. Realistically, I’m facing three more hours of work—the child care—and I’ve already put in a full day at the office.”

Rebecca reached her breaking point on a subway during rush hour last summer. “I was standing on this miserable, crowded, hot train,” she remembers, “coming from a job that doesn’t give me all that much pleasure, to pick up my child, who’d been away from me the whole day, to go home to an apartment so small that my husband and I sleep in the living room on a futon mattress.” That night, Rebecca made a decision. “There’s such a thing as quality of life,” she told her husband, “and this isn’t it.”

Robert was inclined to agree. Although he’d vowed never to leave New York City, the birth of his daughter changed his mind. He worried that they were running harder just to stay in place. While they are scarcely materialistic—the Murrays almost never take vacations, rarely go out for dinner, and spend little on clothes—Robert found they barely met their expenses. “It’s been possible for us to get by with a certain amount of comfort,” he says, “but it hasn’t been possible to accumulate anything, to create a safety net, or even to afford a decent-size living space.”

Last fall, the Murrays began looking for houses outside the city. High prices drove them from Ridgewood, New Jersey, through Bergen County, up to Rockland, and finally into Orange County. They were determined to buy a house with space for a sum they could afford. In December, using a small inheritance, they put down $30,000 on a $90,000 house in Orange County and took out a mortgage for the remaining $60,000. Because they chose a town that was considered slightly beyond commuting distance and was largely undiscovered as a vacation retreat, the Murrays got a lot of house for their money: ten rooms overlooking a lake, just an hour and a half by car from midtown Manhattan.

But even then, the Murrays resisted moving there full-time; the change seemed too radical. Finally, driven by the need to settle on a kindergarten for their child, they made their decision last month. Rebecca gave notice at her job, and in August, after living for two decades in Manhattan, the Murrays will move to a blue-collar town in upstate New York with a population of under 10,000.

Rebecca and Robert are exhilarated by the prospect of more space and less stress. The new house also means they can consider having a second child, something they’ve put off while living in a three-room apartment. On the other hand, the move means that Robert now faces at least three hours of commuting each day; he finds that in itself oppressive. It also means less time for his child, his wife, and his writing. For Rebecca, the move means an uncertain employment future as well as adjustments to life in a small town. The Murrays do not yet own a car, and Rebecca doesn’t even know how to drive.

“We are setting up a life-style which we consciously fought against for years,” says Rebecca. “I’ll be at home, and my husband faces a long commute. But I look around me now, and I see that no matter what life-style people choose, there’s no way the pieces fit. You have to try to get the tightest fit you can, and that means sacrifices and compromises. I feel the way I assume a lot of men feel when they finally realize that they’ll never put on the Yankee pinstripes, never play major-league baseball. It’s devastating. But something had to give. You really can’t have everything.”

To most working parents, Rebecca Murray’s discovery is hardly news. Fully two thirds of two-career couples in the United States work because they must to get by. But mention the Murrays’ dilemma to any young professional parents in New York and you’ll strike a sympathetic chord. Virtually all of them will tell you that they’re preoccupied with the same problems, and that they have yet to find satisfactory solutions. Accustomed for years to having what they want—and addicted to what they have—the prospect of sacrifice is nothing short of terrifying.

Even couples with a great deal of money—enough to have household help, big apartments, and vacation homes—can buy only so much. Certainly their lives are easier, but money can’t buy unlimited time. Working parents at a variety of economic levels are discovering that having it all—two careers, two children, and the income necessary to live comfortably in New York—creates other costs. More and more, they feel overwhelmed by the stress of keeping it all together. They visit chiropractors and physical therapists to relieve their tensions, wake up at night making lists in their heads for the following day. They have too little time for their spouses and their friends. They feel cut off from any larger sense of community. They forget what it’s like to relax. When they slow down long enough to consider their lives, they find themselves wondering whether what they’re getting is worth what they’re giving up.

These couples are members of a babyboom generation that has been searching for answers for two decades now—skipping noisily from one new cause to another. The searching began in the sixties with a common cause: the counterculture taking on the Establishment. But the war finally ended, the enemy blurred, the economy constricted, and graduating college kids suddenly faced a new challenge: making a living. In the Me Decade that followed, the cause became personal growth, but the decade’s legacy has proved less than enduring. The human-potential movement, for all its eclectic forms, produced precious little enlightenment. Is there a zealot still about who extols the long-term values of est, Esalen, Rolfing, primal-scream therapy, or (besides John Travolta) Scientology? As for the flurry of sexual experimentation, its most lasting impact may have been to hasten the spread of herpes and AIDS—and to drive a final stake into countless already troubled relationships.

A new breed of chastened couples emerged from the shambles of the Me Decade. These couples embraced a more businesslike religion: success. There was no room for children. The women, liberated from traditional housebound roles, began making money instead of babies, building careers instead of sand castles. They married or moved in with men on the same path. Free of large financial obligations, these two-career couples had plenty of money. They put in long hours at work and rewarded themselves with designer clothes, meals at restaurants four or five nights a week and dinner parties for eight on the weekends, furniture and expensive trinkets for their apartments, Caribbean vacations in the winter, Hamptons houses in the summer, and Nautilus machines and aerobics classes year-round. They spent what they earned, and they didn’t worry. Save for what? The future was bright.

By the time these couples moved into their thirties, many had built successful careers and sampled most of what money could buy. But something was still missing. Their hunger was for children after all. And, biologically speaking, there wasn’t much time left. Nearly overnight, a second baby boom began. Its progenitors took up their new cause with characteristic passion—and innocence. Sure, having children would require some modifications in their lives, might cut into vacations and nights out, but those were minor inconveniences. The high of having kids would more than compensate. The result, in fact, would be the best of two worlds: family and career.

The women, unlike their mothers, would take brief maternity leaves and return to their careers. To do otherwise would mean sacrificing all they’d worked so hard to achieve—for themselves, and for women in general. What’s more, many of these women were appalled by the prospect of staying home all day with infants. The men would ease the burden by taking an active role in child rearing. These pioneer couples would be better parents in the process, they explained—the father simply for being there, the mother for providing a positive working role model.

For a while, it seemed to work. The sacrifices weren’t all that bad. Going out to the movies gave way to VCR’s and video clubs. Restaurant dinners gave way to gourmet takeout and deliveries of Chinese food. There were some new costs—child care, for example, ran to at least $10,000 a year for full-time help. But that could be endured: After all, mom and dad had careers on the rise.

But then something started to change. It happened first to the women, who discovered that being away from their young children made them feel both guilty and sad. “Quality time” somehow didn’t compensate for “quantity time”—particularly not when the women came home to their children, exhausted from long days at work.

“I remember the first week I went back to work,” says Mary Simms*, a 34-year-old doctor whose child is now twenty months old. “I thought it was a piece of cake. By the third week, it was a disaster. The nanny was with the baby 50 hours a week, my husband worked at home, and I was convinced I’d be number three with my child. I went to my boss and told him I’d like to work four days a week. He said, Sure, no problem. It was ridiculous, of course. I still had the same amount of work. For the past year, I’ve worked six days and been paid for four. I was too embarrassed to go back to my boss. I would love to work a three-day week. The catch is that I’m in competition for tenure with a lot of people who are working full-time. My child, it turns out, is a great, calm kid. The problem is with me. I miss my baby terribly.”

Call it the working-mother blues. By temperament, Phyllis Harlem, 37, is ebullient and energetic. But these days, she frequently dissolves in tears at the frustration of trying to combine a career with a family. A lawyer who works for the city enforcing housing codes, Phyllis is deeply committed to her work. As a result, she gets home at seven or 7:30 each night, feeling exhausted. The long hours at work make time with her two-year-old daughter, Jessica, more precious. “I just want to give, give, give,” she says. “I adore her so, and I feel so much guilt at being away that I’m probably too intense when I’m with her.”

“Quality time” can’t really replace “quantity time.”

Jessica rarely goes to sleep before 9:30 or 10 P.M.—and Phyllis rarely manages to stay up past eleven. That leaves little time for anything else—including her husband. “We never sit and just talk,” she says. “We’re just too tired.” In order to steal a few moments for herself, Phyllis takes the local subway home from work—instead of the express.

Phyllis’s husband, Jerry Siegel, feels just as overwhelmed. A 42-year-old accountant who often works later than his wife, Jerry is, by nature, low key. “It used to be when I got home from my job, it was over,” he says. “Now I go from one demand to another. It never lets up.” Nearly every night, Jerry falls asleep early, only to wake up at 2 A.M., worrying about work or money, or brooding about an argument with Phyllis born of their mutual exhaustion. It’s a vicious cycle: Frequently he doesn’t fall back to sleep until six, only to awake again at seven to face another day.

For Jerry, one of the compensations of working hard has been the opportunity to get away in the summer. He and Phyllis cannot afford to rent a house on their own—in part because they have large mortgage and maintenance payments on the Upper West Side co-op they bought as insiders five years ago. For many years, they’ve taken summer shares with other couples in various houses on Fire Island. This summer, they are in a four-bedroom house, sharing one bedroom with Jessica. The three other bedrooms are occupied by couples who are sharing with their young children. With so many people living in such limited space, weekends are more of the same.

So why try to keep it up at all? “Sometimes,” sighs Phyllis, sinking back in her living-room couch, “I fantasize about retiring, buying a farm, moving to fresh air and space.”

“We wouldn’t buy a farm, Phyllis,” retorts Jerry. “We don’t like farms.”

Phyllis nods sadly. “I guess I’m addicted to New York. You walk down Broadway and it’s a scene, an event. I find it exciting—and I love the idea that Jessica is exposed to so many different people and experiences. I don’t want to deprive her.” She shakes her head. “I’m stupid. We’re struggling, and I want to have another kid. I’m not willing to give up anything. I’m spoiled; I know it. We have so much more than most people. It’s just I didn’t expect it to turn out this way. I work so hard, come home, see my kid for a couple of hours, fall asleep, and then it starts again. Where’s the fun?”

Working part-time is an appealing alternative for Phyllis, but even if her employer agreed, she and Jerry feel they couldn’t afford to sacrifice her income. Joan Breibart, 44, mother of two sons, 7 and 4, shares many of Phyllis’s conflicts but has never considered working part-time. Money isn’t a problem. Her husband, Doug Bittenbender, 44, is a successful businessman whose income would be enough to support the family.

“To me, working—paying half the bills—is part of my obligation in this marriage,” explains Joan. Until recently, she was an executive in a company that runs hair salons, and now she’s a consultant to health clubs. “This is a city built around work,” adds Joan. “Your whole identity is tied up in it.”

Joan gets satisfaction from what she does, and her family lives comfortably in a sprawling apartment overlooking the Hudson. They keep their BMW parked in a nearby garage and drive on weekends to their country home in the Berkshires. Both of the boys attend private schools, and the family has a live-in housekeeper. But even with all this, Joan finds there is much that she gives up.

“It’s a treadmill,” she says. “Marriage becomes all business, no romance. The only thing you talk about is who’s going to pick up the child, who’s going to call to get the refrigerator fixed, who’s going to make the dentist appointment. At one point, during a very tense period, I realized I hadn’t really talked to my husband in two months. We ended up taking a hotel room for two nights, just so we could be alone. I know it’s taken a tremendous toll, that the quality of time with the children isn’t as good as it should be. But you can’t stop, because that would be worse; you’d never be able to catch up. In my mind, I should be able to do it all, so I try. You don’t have time to think about the whys.”

Indeed, too much introspection can be fatal. “I find that the mothers who feel ambivalent about working versus staying home are deteriorating rapidly,” says Susan Weissman, executive director of Park Center for Pre-Schoolers, which operates three private day-care centers in Manhattan. “The parents who do best are those who have a very positive outlook on working, which they impart to their kids. But they also have to become super-organized. Most have a system—putting out clothes at night, a ritual for bedtime, a plan for everything that never varies. If it did, there’d be chaos.”

The head of another Manhattan day-care center takes a sharper view. “Many of these parents become robots,” says this observer, who requested anonymity. “They bring their kids to school at 8 A.M. and return at 6 P.M. schlepping boxes of diapers. I don’t know how they do it, but I understand why they don’t get too reflective. They’re scared of what they’d find: ‘I have these kids, but I hardly see them. I have this job I work very hard at, but what does it really mean? I manage to get it all done, but I never stop running.’ Those are scary thoughts.”

The scariest thought for many is change. “We’re talking about the need for people to make realistic choices,” says Felice N. Schwartz, president of Catalyst, a nonprofit organization that works to encourage flexible approaches to career and family. “The problem is that people haven’t yet absorbed the necessity for trade-offs,” she says. “It’s not realistic for women—or for men—to think that they can pursue high-level careers and be primary players in their children’s lives and have time for their spouses and themselves and play a role in their communities.”

In the past, of course, roles in marriages were more clearly separated—and no one was expected to do it all. At its annual award dinner, in March, for example, Catalyst honored four women who’d excelled in corporations. The male chief executives of the companies—who handed out the awards—had fourteen children among them, each raised by a wife who stayed at home. Among the four women honored, only one was married, and only one had a child. “The explanation is simple,” says Schwartz. “These women didn’t have wives at home to raise their children. They sacrificed family to have their careers.”

The opposite choice is being made by an increasing number of women who spent the past ten or fifteen years building careers—but now find their priorities shifting. Prompted by an unexpectedly powerful desire to spend more time with their children, more and more women who can afford to—and who can convince their employers to go along—are cutting back.

At the Park Center on West 86th Street, for example, nearly all of the sixteen mothers of this year’s class for four-year-olds worked full-time before their children were born—and returned to their jobs after brief maternity leaves. Today, fewer than half of these mothers still have full-time jobs. Of the mothers of children at the Park Center on West 82nd Street, 25 percent work part-time. In turn, their children now attend part-time.

This phenomenon, however, may be more characteristic of the West Side. At the Park Center at 35th Street near Madison, nearly all the mothers continue to work full-time. The same is true at Seton Day Care Center, located in the New York Foundling Hospital on Third Avenue at 68th Street, and at the Children’s All Day School on 60th Street at Lexington Avenue, where all but one of approximately 80 mothers work fulltime.

But that doesn’t mean these parents are immune to the pressures. “I think nearly every one of them would rather work three days a week than five,” says Joy McCormack, director of Children’s All Day. “But in addition to the economic impact that would have, I think they’re afraid they’d lose control of their jobs. And the truth is, they probably would.”

Those concerns haven’t deterred other women. “I just felt this intense, instinctive, biological longing to be with my child,” says Ellen Richards*, 32, an East Side psychiatrist who has a year-old baby. Ellen became pregnant not long after beginning a challenging job as the assistant director of an outpatient clinic in a Manhattan hospital. By then, she’d already invested ten years in her training: four in medical school, one as an intern, two in a specialty she later decided to leave, and three as a psychiatric resident. After the birth of her baby and a four-month maternity leave, Ellen returned to work, reluctant from the start to leave her child but eager to pursue her career. The conflict quickly became intolerable. “My heart would break every time I went to work,” she says. “The only time I could work well was when I was busy. Otherwise, I just felt longing.”

To be alone, one couple spent two nights in a hotel.

Last month, she decided to cut back to three days a week—retaining her hospital affiliation but giving up her management responsibilities. The choice was bittersweet. Economically, it meant a loss of at least $10,000 a year—perhaps as much as $20,000. The psychological impact was even stronger.

“Within days, I became a second-class citizen at the hospital,” Ellen explains. “They moved me out of a big office into a horrible back office. My job had been 100 percent supervisory—and suddenly I was told I would have to see a number of hospital patients each week. I lost power and status in a job where I had a lot of room to rise. I am also convinced it will be hard to step back in after several years away.” Still, Ellen feels she made the right decision. “I am definitely torn, but when I think about having a second kid—which I want to do—the handwriting’s on the wall. I’ll want to be home.”

Betty Jane Jacobs, a Park Center mother working part-time, cut back shortly after the birth of her son, Joe, now three. She had been working full-time for Legal Aid. Now she works three days a week for her husband’s firm. The other two days she spends with her son.

“I’m aware that I was lucky to even have the choice,” says Betty Jane. “The hardest part of cutting back for me was giving up the ambition. I never wanted to be rich, but I did want to be famous. You’ll never get famous doing law part-time.” For now, Betty Jane is surprised at how happy she is with her decision. “The truth is, I don’t miss what I gave up so much anymore. I find being Joe’s mother to be very rewarding. It fills me up.”

Betty Jane belongs to a group of working mothers that meets regularly. There are seven lawyers, and all but one of them have either cut back or switched into less demanding jobs since having children. Among them is Jennifer Patton*, who works for the state and had her second child last year. Now she works half-time. “I switched from a visible, high-pressure job into a much lower-profile, lower-pressure job in a different bureau,” she says. “I’ve gone off the track, but at this point I don’t care. I’m much happier now. I always felt women should not take it as a goal to be like men. Women have their nurturing side more in place. To me, the point of women’s liberation is to be able to do what you want to do.”

Some women, though, are more ambivalent about cutting back—and resentful that men don’t seem to face the same dilemma. “At my hospital,” says Mary Simms, “the women physicians who have children nearly all hold the less high-powered jobs. They’ve taken those jobs by choice—so they can be home—but the result is a huge difference in prestige and in income. I’m talking about $35,000 versus $200,000 in some cases. Because to build a private practice, you need to be available when more senior people don’t want to work—and that means being on call all the time. Women with children are much more reluctant to do that than men.”

Though many couples seem to be returning to traditional roles, Felice Schwartz of Catalyst argues that this is just a transitional stage. “Already women are entering every field and achieving at the same rate or higher rates than men for the first five or six years,” says Schwartz. “But then, when the clock begins to tick, the women have children, and socialization seems to set in. As a society, we still believe deeply that nobody can love a child the way a mother can, and therefore that mothers should be home when their children are small. That is compounded by the inequality in pay—the man usually earns more, and there’s an economic motive to follow his paycheck.

“But all of that is changing. Sixteen percent of women now earn more than their husbands. By the end of the decade, more than 50 percent of the work force will be women. And more and more, men are discovering the rewards of parenting—right from birth, when they coach their wives through delivery. When parenting truly becomes interchangeable, both men and women will have more flexibility—at home and at work.”

Schwartz uses her own life as an example. The mother of three children (among them, me), she stopped working in 1951 and stayed home for eight years until we were all in school. My father, a scientist, worked long hours and was rarely home. “We never chose our roles,” says my mother. “They were determined for us. But in retrospect, I think it would have been better if I had continued to work. I was intensely goal-oriented. If it had been socially acceptable, your father, who is wonderfully nurturing, probably would have been happier to spend more time at home. The whole family would have benefited.”

There is little question that many men are more involved as parents than their fathers were. “I don’t think there’s a woman around more torn than I am about career versus being with my child,” says Robert Murray, who will soon begin his three-hour commute. “I truly miss my daughter when I don’t see her. I feel resentful that society still isn’t flexible enough to allow me to structure a life where I can earn a reasonable income and still have a reasonable family life. What I mean is that to have a full-time career and earn, say, $50,000 takes a great deal of time. My ideal would be to share a job with my wife—both of us work half-time for $25,000—and both be home half-time. But who would let us do that?”

A growing number of New Yorkers who vowed they’d never move to the suburbs are beginning to reconsider now that they have children. And like the Murrays, most of them feel great misgivings about the choice.

In the fifties, the suburbs were still the promised land. Young parents, many of whom came of age in the Depression, moved there enthusiastically. The suburbs were viewed as an ideal place to raise children. But those children, who grew up in the sixties, are today’s parents. They may wistfully recall the space and material comforts of their childhood—particularly if they now live in tiny Manhattan apartments. But they often remember the suburbs as bland and arid. They aren’t so quick to accept that the suburbs are better for themselves or for their children.

Martin Asher, 40, and his wife, Judy, 39, recently bought a house in Westport, Connecticut. But they remain ambivalent about moving from their four-room rental apartment in Manhattan, where they live with two children, seven and four. Both the Ashers grew up in New York, and both work in the city. Martin is the director of the Quality Paperback Book Club, and Judy teaches tumbling to kids at Judy’s Gym on West 81st Street.

For more than two years, the Ashers circled ads in the Sunday Times real-estate section and trooped around with brokers looking for an affordable New York apartment with at least one additional room. The search proved fruitless. Then one day last fall, they had lunch with a friend who lives happily in Westport. The Ashers drove up and bought the first house they saw. To pay for it, they sold a weekend house they owned upstate in Hudson—two and a half hours from the city.

“We’re going to try living in Westport this summer as an experiment,” says Martin. “I’ve never commuted in my life. I feel like it’s a matter of trade-offs: the convenience of being able to walk to work and have everything nearby versus things like fresh air and space. You just have to decide what’s most important to you.”

There’s one small hitch. “We can’t decide,” says Martin. “A lot of things are important to us, and on any given day it might be one instead of another. It used to be you moved to the suburbs for the children. But on some level, we still think of ourselves as children. As for my children, as much as they love the backyard, they also love the energy and excitement of New York. We were in Westport the other day, and I said to my son, ‘Would you like to live here?’ And he said, ‘Yes, I’d like it very much. But can I still go to my school in the city?’ It even occurred to us—why not let him do that? I would commute with my son, drop him off at school, let my wife’s mother pick him up, and then commute back together when I finish work. We may even end up with some kind of modified double residency—weekdays in Westport, weekends in New York. We’re trying to keep all the options open.”

Judy Asher puts the problem more succinctly: “So far, we haven’t been able to give up anything.”

“The other night,” says Martin, “I walked out of the house in Westport, and it was warm but so foggy you could hardly see. I found myself thinking, ‘This is really beautiful.’ But then I thought, ‘If the same thing happened in January, and I’d just gotten off the train at the end of a long commute, would I still find the poetry in it?’ “

The answer of course, is that moving to the suburbs is a trade-off. Jody Gaylin, 33, moved two years ago from the Upper East Side to Hastings before the birth of her third child. Her husband, a network news producer, commutes.

“For me, the city is more fun, more exciting, less isolating,” says Jody, a freelance writer who thinks of herself foremost as a mother. “But finally, I just had to face facts. I was getting awfully tired of sitting on benches in playgrounds, supervising kids who didn’t need my supervision, and paying ridiculous amounts of money so my children could be taken on a bus to baseball fields many miles away.”

Jody thinks the sacrifices have been worth it. “I was dragged from the city kicking and screaming,” she says, “but now I couldn’t be happier. It’s fantastic to be here with kids.”

Not everyone feels such equanimity. Like the Ashers, Richard Simon*, 37, and his wife, Patricia, 35, bought the first house they looked at in Westchester. But then they got cold feet and tried to sublet the house while they reconsidered leaving the cramped New York apartment they shared with their five-year-old and their newborn. There were no takers on the house, however, and they could not carry the costs of two homes. In December, they sublet the New York apartment and moved to Westchester.

Cutting back on the job can sink a promising career.

“Maybe it’s that I just don’t have enough inner repose to be out here gardening and enjoying nature,” says Patricia. “I want action and excitement, and this place just doesn’t have it. I’m not even convinced it’s such a great place to raise kids. I went to visit the public school, which is supposed to be good, and the kids were all lying on the floor giving each other noogies. Then the teacher started reading a letter to the class from their pen pal in Argentina. It began, ‘We are ruled by generals.’ The teacher never even mentioned that there’s been a changeover to a democracy in Argentina.” Most parents probably don’t worry about such political distinctions when it comes to five-year-olds. Patricia did.

“I was horrified,” she says. “That alone was enough to turn me off to the school.” The Simons would be happiest if they could send their daughter to Brearley, but they’ve decided commuting to Manhattan is simply too far. Instead, they’ve compromised on a private school in Riverdale.

By contrast, there are a growing number of New York parents who are having second thoughts about sending their children to private schools. The cost—$6,000 a year and up—is one factor, but so is the fierce competition for admission, in which even four- and five-year-olds are subjected to tests and interviews.

“We refused to put our daughter through it,” says Robert Murray, who will be sending his daughter to a public school upstate this fall. “It just seemed like inordinate stress, and I wasn’t comfortable with the whole atmosphere of elitism.”

Elaine Cohen, 39, who last month moved from Manhattan to Katonah with her husband and two-year-old son, feels enormous relief that she now needn’t face the private-school process. “I began to worry that I’d turn into something I didn’t want to, that I’d start to feel competitive for my child to get into one of three or four schools, and that I wouldn’t like myself for it,” she says. “I didn’t want to feel the pressure. And I didn’t want my son to feel the pressure. There’s plenty of time for that. The key to success and happiness is not necessarily going to Dalton.”

Audrey and Lee Manners learned that lesson painfully. After their five-year-old daughter tested well last fall, they made applications to four top private schools. All four put her on their waiting lists. That solved the Mannerses’ ambivalence about the suburbs: In the fall, they will move from their Upper West Side co-op to their new home in Ridgewood, New Jersey.

Martin and Judy Asher went through the private-school application process once for their son, but decided once was enough. This spring, looking for alternatives, they visited P.S. 87, a public school on 78th Street near Amsterdam Avenue. For several years, the school’s principal, Naomi Hill, has successfully recruited the children of parents who might not otherwise have considered public school. The Ashers—who fit Hill’s profile—were impressed both by the mix of the student body and the unexpected richness of the school’s resources. They have enrolled their four-year-old for the fall.

In the end, all of these second thoughts—public versus private schools, the suburbs versus the city, careers versus family—are merely expressions of something deeper. Even the most driven working parents are recognizing that the costs of having it all may be too high. Rethinking where to live, or how to balance kids and work, sometimes makes these couples feel another, less tangible hunger—one they can’t always define precisely.

That hunger helps explain why, when they see the movie Witness, they respond so passionately to the scene in which a community of Amish men, women, and children come together to build a barn for a neighbor. Or why many young parents felt uncharacteristic—sometimes even uncomfortable—stirrings of patriotism as they watched the Olympics last summer. Or why they latched on so quickly to Gary Hart’s presidential candidacy last year, when he seemed to be appealing to their best and brightest instincts—pragmatic and ambitious, but also caring and concerned. And why they fled from Hart when he came to represent the side of themselves they liked least—a willingness to put success ahead of principle, ambition ahead of compassion.

“For several years now, this generation has been preoccupied with getting ahead, with winning, with success,” says Florence Skelly, president of Yankelovich, Skelly and White, a research firm that monitors social change. “They haven’t had any compelling ideological goals or moral concerns, and I think that’s created a void. These same people who led us into this strategic, competitive age will, I think, lead us into the next wave. And I think that wave will have a much more moral, ideological cast.”

Indeed, Patrick Caddell, the pollster, argued recently that baby boomers retain “a powerful, deeply embedded instinct for community, for activism, and for change.”

“I love what I do,” says Laura Popper, a 39-year-old East Side pediatrician with two daughters of her own, “but I can’t stand what it does to me.” Recently, she attended the funeral of a family friend. Her parents came, and so did scores of their friends. “I realized that my parents have this incredible, extended social and political network,” says Popper. “The women nurtured these relationships. Many didn’t have full-time jobs, so they had time. And they worked together on causes. They became connected through the meaning in their lives. Where’s the time for me to do that? I see my friends by giving their children the last appointment on my calendar. My whole life was focused on being a doctor. I’m about to turn 40, and I’ve been working all these years, and my kids are starting to experience all this stuff, and I’m saying, ‘Hey, wait, I wanna be there, too.’ I go to all the school plays and functions, but that’s not enough. I want to be there when they don’t care if I’m there.”

For James Atlas, 36, A writer, the hunger is to be freed from devoting so much time and energy merely to getting by. Atlas is married, has a two-year-old daughter, and lives in the West Seventies.

“You think you have the freedom to choose, only to discover, living in New York, that certain values choose you,” he says. “Sometimes I feel almost imprisoned by their ubiquity in the culture—that I have come to want things just for the sake of wanting them. It scares me to work so hard, buy so little, and yet have nothing. Not to play this game would be a tremendous achievement.”

Carol and Howard Kirsch are trying to do just that. They live now with their two daughters in Washington Heights, near the Cloisters, at the northern tip of Manhattan. They have a large river-view apartment that they were able to buy three years ago for the same price they got for their tiny dark apartment on Central Park West. The move seemed to solve their key problem: space.

But during the past several months, Carol, 37, who works in employee relations at Time Inc., and Howard, 40, who works as a technical manager for NBC News, have been reconsidering their priorities—again.

“I want to have more time,” says Howard, “more time to listen to music, be with my kids, to do housework, which I happen to enjoy, to play racquetball.” Carol, too, would like more time to be with her children and with her husband. She also yearns to live in a community where she could feel more involved. Carol is motivated by what she sees happening to her eight-year-old daughter, Rebecca, who attends Hunter, one of the city’s most prestigious public schools.

“The atmosphere is so competitive that my daughter feels she’s not smart,” Carol explains. “And she’s on a track so filled with things to do that she has no time to play. Childhood is too short for that.”

The Kirsches doubt the suburbs are the solution. Howard has no interest in commuting. Carol sees little likelihood that she’ll find the sense of community she seeks in a suburban bedroom community.

For the short term, the family is considering a three-month European trip with the children. But Carol’s long-term hope is that she can convince Howard to move to a small town—say Burlington, Vermont—even if it means a substantial loss of income.

“I’m ready for a real life change,” says Carol.

The Kirsches aren’t out to lead a movement from the fast lane back to the calm of the country. They’re looking for alternatives, not answers, and they’re willing to give up some things in order to gain others.

But perhaps that’s the new wave—the notion, as Rebecca Murray puts it, that the pieces don’t all fit. Perhaps the best hope is figuring out what really matters most, factoring in some sacrifice and compromise, and finding solace in the fact that there’s no law against living a life that blends the selfless and the selfish.

Making that accommodation, however, would force a generation of baby boomers to accept a prosaic fact of life they have skillfully managed to resist for nearly twenty years. It can be summed up in two words: growing up.

Test Your Staying Power

Part 1: Are You Addicted to the Fast Lane?

(Unless otherwise noted, score 1 point for each yes answer.)

1. Do you read the ads in the Sunday Times real-estate section every week, even though you can’t possibly afford a bigger apartment? (Add 1 point if you read the real-estate section before the front page; add 1 point if you also read the “Luxury Homes” ads in the Times Magazine and the “Town & Country Properties” in New York Magazine.)

2. Do you complain constantly that you don’t have enough time for anything, but rationalize that there is no way out?

3. Is sex mostly a fond memory? (Add 1 point if you can’t remember; subtract 1 point if you do have a memory but it isn’t fond.)

4. Did you make applications for your child to more than six private schools? (Add 1 point if they included at least three of the following: Dalton, Trinity, Brearley, Chapin, Horace Mann, Collegiate, Nightingale-Bamford, Spence.)

5. Are real-estate prices and private schools the two most frequent topics of conversation when you attend dinner parties or take your children to the park? (Add 1 point if the third most frequent topic is the difficulty of finding good help.)

6. Have you suffered, for no apparent reason, from any of the following ailments during the past six months: insomnia, lower-back pain, upper-back pain, stomach problems, dizziness, hives, migraine headaches? (Add 1 point for each ailment; add 1 point if you’ve seen a chiropractor, masseuse, or reflexologist six or more times in the past six months.)

7. When people ask why you stay in Manhattan, have you ever answered, “I didn’t move to New York in order to live in Brooklyn (or Queens) (or the Bronx)”?

8. Do you spend every dollar that you earn, even though your earnings have increased beyond anything that seemed possible ten years ago?

9. Do you consider three or more of the following items necessities: take-out Chinese food, a VCR and membership in a video club, a health-club membership, a car and garage, full-time child care, a housecleaner, a summer-vacation getaway? (Add 2 points for either of the following: a mobile phone for your car, weekend child-care help.)

10. During the past two years, have you exaggerated your income in order to qualify for a mortgage or any other form of credit? (Add 1 point if your mortgage and maintenance payments or your rent exceeds 40 percent of your gross income.)

11. Are you afraid to leave New York because you’d miss the cultural diversity (even though the closest you’ve come to a cultural experience in the past year was stopping to listen to a guitarist in Central Park sing songs from the sixties)?

12. (Replaces question 11 for those who have moved out of the city) Do you still do one or more of the following: return to the city at least two weekends a month, keep your child enrolled in a New York City school or day-care center, bring dinner back from the city more than four times a month?

Scoring

20 or more points: You are an excellent candidate for hospitalization for nervous exhaustion. Immediately take a one-month vacation on a distant island with no phone. If you must, rationalize the time off as a business investment. You will be cooling off an engine that you’ve been running too hard.

15-19: Danger of overdose. Take a three-day weekend.

10-14: You are in the swing category—moving very fast but probably wondering about the direction.

6-9: You have managed to resist trying to have it all. Either you are very rich or very independent.

5 or fewer: You have long since left New York City.

Part 2: Are You Having Second Thoughts?

1. Do you feel embarrassed that you answered yes to so many of the questions above—or stretched the truth outrageously in order to answer no?

2. Do you feel guilty about how little time you spend with your children, and/or your spouse, and/or your friends, and/or on social causes? (No credit if you feel free-floating guilt.)

3. Have you given up reading the Sunday Times co-op ads—and turned instead to homes in the suburbs? (Add 1 point if you’ve looked at ads for homes more than 75 miles from New York City.)

4. Have you visited the public school in your area and seriously considered sending your child there? (If you answered yes but were referring to Hunter College High School, subtract 1 point. Hunter is strictly fast track—and you know it. If you are actually sending your child to public school, add 2 points.)

5. If you hear one more conversation about real estate, schools, or the difficulty of finding good help, is there a reasonable likelihood that you’ll throw up?

6. Have you done any of the following in the past six months: consciously decided to stop working nights and/or weekends; given up jogging, Nautilus machines, or weight lifting; taken up walking, swimming, and/or yoga? (Add 1 point for each.)

7. Have you found yourself fantasizing about the advantages of moving to the suburbs? (Add 1 point only if this is something you vowed you’d never do.)

8. Have you consciously resisted buying something you wanted during the past year, simply in order to sock away some money for the future? (Subtract 1 point if you are saving for a Jaguar.)

9. As part of your new resolve, is this the last issue of New York Magazine you will ever read?

Scoring

15 or more points: Maybe you’ve gone too far. In all likelihood, you’ll lead a new wave back to New York in the next five years.

10-14: You are on the cusp of a life change. You’ll probably feel better if you make it.

5-9: It is just beginning to dawn on you that something’s not right. But you’re not yet ready to do anything about it.

4 or fewer: See Scoring for Part 1, 15 and above.

—T.S.

* The names of couples denoted by an asterisk have been changed at their request.