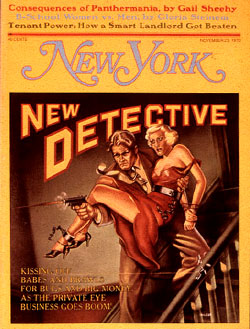

From the November 23, 1970 issue of New York Magazine.

A whimpering, tortured, dull-witted black was led into a Connecticut bog last year and there took a bullet in his head. Implicated in his death was Bobby Seale, chairman of the Black Panther Party, who is scheduled to stand trial this week in New Haven. In this second of a two-part series, Miss Sheehy examines the onset and the pathology of the revolutionary fever—and the paranoia—that gripped the Panther movement and led directly to the destruction of the party in Connecticut and nationwide raids, trials and more deaths.

New Haven, the Model City. New Haven, bellwether for the nation in urban redevelopment. New Haven, where poor black folks sat quiet on their porches while white liberals spoke for them and black bourgeois families walked in a flank to the white pocket-book Congregational Church and where the brush fires of black militancy—thanks to God and Yale—were banked and under control. So went the propaganda as America’s war on urban blight bumbled through the sixties.

Warren Kimbro was a good black burgher of New Haven. Until 1969, when he caught revolutionary fever—Panthermania—and killed a man, Warren Kimbro was in the black middle.

Imagine, now—to catch the schizoid pull on Warren Kimbro over the past ten years—that you are standing with one foot in each of New Haven’s two worlds:

One foot is on Yale Green. You are in the castle garden encircled by garret tops and gargoyles leaping off the turrets of a great university. Mighty gates curl back benevolently, beckoning … yes, you … into courtyards of autonomous Oxonian colleges. (But you are dark-skinned and never finished high school.) The people all around are young and vanilla with raspberry cheeks and the tell-tale moles of high breeding.

The other foot is in Congoland. In the bathroom of a rooming house. This is one of the shooting galleries along Congress Avenue and you are chipping a little heroin under the skin of your knee. It doesn’t show there.

Congoland is a wedge of streets which form the core of New Haven’s seven inner-city neighborhoods. It is near Yale. But on each of these corners the brothers of college age, unemployed, stand around in little clots, their young muscles bumping up through short-sleeved shirts, with nothing to do but rap. And rap some more, or hustle, or sip a little vodka, or shoot. Across the street from the shooting gallery sags an apartment house, long ago condemned by the Redevelopment Agency. Paste-ups of old Panther newspapers hang off its brick face. Like dead skin off sunburn. The famous Bobby Seale cover is there. You would recognize it as the drawing made of Chairman Seale being transported from the Chicago conspiracy trial to the New Haven murder trial. Bobby is strapped into an electric chair. His eyes bulge over the headline: THE FASCISTS HAVE ALREADY DECIDED IN ADVANCE TO MURDER CHAIRMAN BOBBY SEALE IN THE ELECTRIC CHAIR But you are too busy to absorb local color. Police have these shooting galleries staked out. You keep one eye on the exit. This is a constant about being black. It goes for the “distinguished colored gentleman” who serves at Yale club tables as well as the addict. One eye must always be kept on the exit.

Warren Kimbro passed 36 years picking his way between these two extremes. For the well-behaved Negro he was right on schedule.

Quit high school to follow his brother into the Air Force. Came out of the service in 1956—two years after the Supreme Court insisted, finally, on integrated schools. But Warren was already 22 and running on the old black schedule. Not quite certain what could be done with his life. His assets were small: a handsome face, gentle eyes, evangelical urges and the GI Bill. He was also wiry and tense, but not one to complain out loud. Warren trained as a clothes spotter. That put him in the dry cleaning business for the next six years. Still on schedule, he switched to making pastries in the Hostess cupcake factory.

“There was no colored, I mean, no black foremen of that time,” recalls a black co-worker, Jerry Nelson. “Warren’s function was, he was a fruitmaker. Like me. The first community activity Warren got involved in was Residential Youth Center. That wasn’t till 1966. But to me, he’s always been an extremist.” To Jerry Nelson, as to most black New Haveners, “extremist” means anyone willing to act on what he believes—all the time.

Black Panthers in New Haven? Too absurd to consider, even in 1968. The Panther Party was still a mysterious aberration of California-style nut politics. Black New Haven read about such things while white New Haven earnestly bulldozed. Bulldozers were the great weapon in the war on urban blight. Bulldozers ate up the ugliness and plowed under the obvious. City fathers ran their bulldozers over New Haven’s inner-city neighborhoods for twelve years. By the time black folks woke up, downtown New Haven was gone. Removed. To be renewed. Dust soup.

Five thousand living units were demolished between 1954 and 1966. A scant 1,500 units replaced them. Of these 1,500 (according to architectural scholar Vincent Scully), only twelve public-housing units were designed for low-income people, 793 were luxury housing and the rest went to middle-income and elderly New Haveners.

Where lives and tacky bars and derelict frame houses went down, a new architect’s supermarket went up. Former Mayor Richard Lee, working with Yale for political mileage, sought the biggest names in architecture. The city lavished design excellence on such (humanist?) projects as Eero Saarinen’s giant parking garage … a Knights of Columbus building by Kevin Roche … a rubber company headquarters by Marcel Breuer … Philip Johnson’s new Epidemiology Lab for Yale.

It was a fair example of urban redevelopment in America, to quote the scornful Mr. Scully—”Cataclysmic, automotive and suburban.”

Forty per cent of black New Haveners were affected by re-development. They began to catch on. Politicians were playing the old game. The way they were spending federal renewal funds to finance capital improvement projects amounted to socialism for the middle class; the poor had to get along on free enterprise.

New Haven emerged with its nose powdered—a “model city.” A shopping mall, graced by the Park Plaza Hotel and a Macy’s branch, encloses the sounds and smells of modern commerce. The air is washed in cosmetic perfumes and essence of Muzak.

New Haven’s new downtown is dedicated to drivers: to docile black families who drive stubby Mercuries and to the farmers who roll in from the Naugatuck Valley to shop every Saturday. Above it all soars the basilica of Saarinen’s cathedral for cars. Yes, another St. Peter’s for an American Model City.

“… Panthers in New Haven? Too absurd. In 1968 they were still a mysterious aberration of California-style nut politics …”

Waiting … Warren Kimbro kept waiting for an opening in community work. Married to a pretty New Haven girl, father of a son and daughter, he went back to pass the high school equivalency test. When the Development Agency took shape in 1963, he applied to be a housing inspector. “High school diploma required.” Friends advised Warren to lie about how he got his diploma. Not me, Warren said, these things have a way of catching up with a man. “Application denied.”

To appease the finest black families, architect John Johansen was commissioned to do a new Dixwell Avenue Congregational Church. Something about it—the hidden windows?—makes white people hurry past. A big circular fortress, the church backs off the street into a dust lot. Secretive, defensive. Every window is hidden behind a gusset of concrete. It’s as though the architect’s hand was guided by news accounts of the future to design a refuge from the urban race war.

While New Haven’s so-called redevelopment was going forward, disturbances tripled in the inner city. Rioting bent the city to its knees in the summer of 1967. The Irish and Italian shore towns are still nervous with the memory. A gun by the bedside goes without saying.

But community groups had been quietly organizing a politicized black citizenry for some time. The riot only blew the whistle on shocked white liberals. It signaled the beginning of real fights to make poverty programs work for people, of empty churches being reborn as teenage soul centers, and of rising expectations.

Passing thirty, Warren Kimbro broke away from the security of making fruit pies. He volunteered as a youth counselor for Community Progress Inc., supported by federal funds. He loved kids and worked conscientiously. CPI promoted him to Community Coordinator in his own neighborhood. Things were happening, but slowly.

By 1969 a strong Black Coalition got itself together. Combining the forces of some 40 local groups, it began to turn the tide. Residents of the inner city insisted on manning their own redevelopment offices. The “community advocate” became a recognized figure in negotiations between black citizens, the mayor and Yale.

Into this climate of fragile, hard-won hope burst the Panthers.

To be exact it all started in January, 1969, with one Panther sister, Ericka Huggins. She was the wife of a New Haven favorite son, John Huggins, who strayed to UCLA and rose to Panther leadership in Southern California. He died a revolutionary martyr in a shootout with rival black militants. After Christmas, when John Huggins’ body came home to New Haven, the widow Ericka came with it.

From the moment Ericka hit town, little tremors fanned out and quickly grew into barbaric rumors.

Had Ericka brought any of those crazy California Panthers back to Connecticut? The Hugginses wouldn’t talk. Inquirers dialed a knowledgeable and sympathetic white man to ask about the girl.

“Ericka was described to me quite frankly by a young black community leader,” the white man began, confidentially speaking, “as a black Ilse Koch …” letting this penetrate … “Koshh, you know, the Nazi. Of course the black community here is in terror of the Panthers. And frankly, I am told by some young militant black men that the Panther women are uncontrollably aggressive. Man-haters. They take it out through the Panther movement, you see.”

“Ericka Huggins? Let’s put it this way,” said a white attorney. “If you invite Ericka to a party she’ll bring the boards and you supply the nails. A born martyr.”

An appreciative black Yalie, though highly skeptical of the Panthers, looked at Ericka differently. “We’ve had Erickas all our life. If it weren’t for the toughness of black women, black men would all be like buffaloes. Extinct.”

Early February, 1969. Showdown between Ericka and the Hugginses. The elderly couple wanted Ericka to do right by John’s baby, their granddaughter—a tiny precious chip off their son and only three weeks old. Her name was Mai.

“We’ve got plenty of room for you and the baby. You won’t even have to buy food.”

Ericka insisted on her own place.

Then why didn’t she leave New Haven, forget the Panthers and raise John’s baby safe!

The Hugginses baptized Mai but lost the showdown. Baby and mother vanished into downtown New Haven.

Ericka Huggins and Warren Kimbro? Their names were linked through the rumor pump, though the connection was unclear. An affair? The rumor pump ran it through again: It’s Ericka’s way of pulling men into the Black Panthers. First she seduces them, then she ridicules them.

In this form the rumor reached Betty Kimbro Osborne, Warren’s older sister. At the same time Ericka Huggins tried to contact Betty Osborne. A clash between the two women was inevitable.

Ericka was taller than John. Of all her imposing characteristics, Ericka’s tallness was paramount. Rising five feet, eleven inches, slender and firm, energetically 22, she strode around town in a denim work suit, legs cutting along like flashing scissors—and very soon unmistakable.

This is Ericka Huggins, Connecticut Panther, Party Minister of Political Education, is how she announced herself. Not always fiercely, sometimes with the disarming breathlessness of a little girl. She had a little-girl face. When the occasion called for softness, Ericka’s face melted into caramel smiles and she could preside over meetings with the composure of a Rose Bowl queen.

New Haven had never seen anything like her. People wanted to mourn for John Huggins’ brave widow. Ericka Huggins wanted to wake them up.

Betty Kimbro Osborne is no less beautiful or direct than Ericka, but older. Forty. Tense. A feet-on-the-ground realist. She is in the black middle as a Yale faculty wife and not about to apologize for it. From a family of eight, with all her sisters living unremarkably in Ansonia, Derby, New Haven and one brother on the Miami police force, Betty alone married up.

Ernest Osborne, her husband, is director of community affairs for Yale. Name any project working between New Haven’s town and gown segments and Ernest Osborne’s name is on it. Though probably in fine print. Modest and principled, reflective behind his horn rims, Ernest Osborne has the quiet man’s touch. His name is respected in all circles. In fact, Ernest Osborne is one of the best hopes New Haven has in the wings for a black mayor. Or was.

Ericka avoided confronting Mrs. Osborne on her own turf. Too alien. Together Betty and Ernie Osborne answer the door of their Olde Connecticut Colonial in matching dashikis, designed by Betty. It’s a mixed block with black children and white fuzz and backyard barbecues. Somehow the Osbornes and their two high-spirited teenage children are more New York. (Ernie went to Benjamin Franklin High School and attended Long Island University.)

The house is heavy on imports from East 57th Street in Manhattan: Design Research pillows and Mexican prints and Scandinavian serving bowls, all culled from conference trips. Form is important to Betty Osborne. But so are people. She has worked seven years for New Haven’s Redevelopment Agency. (What the Panthers would call “a housefolk gig.”) She also belongs to Black Women for Progress.

One would not like to be the enemy of either of these women. Betty Osborne combines the high carriage of an Essence model and the tenacity of a Jewish mother. Ericka Huggins is taller and has nothing left to lose.

Ericka finally confronted Betty by phone. “I hear you and Black Women for Progress want to whip my ass and run me out of town,” she said.

“Who gave you that piece of information?”

“Never mind who. Your organization doesn’t want people coming in from out of town and breaking up other people’s homes, right? The fact is I’m here to help people.”

“If you won’t give me your sources, don’t call me up with that dumb —-,” said Betty Kimbro Osborne. “In the first place, I think you should leave town and raise your daughter. In the second place, when and if I get ready to go after your ass I won’t need any women’s group to do it.”

Mid-February. Their faces broke into the dinner hour on Channel 8 news. Ericka Huggins and Warren Kimbro, along with a Bridgeport Panther by the name of Jose Gonzales. Ericka did all the talking. New Haven was getting together a brand new Black Panther Party chapter.

Betty Osborne began to twitch and jump in her sleep. Her brother wouldn’t answer the phone. His family ties were abruptly suspended—he belonged to something else.

“Don’t interfere,” Betty’s husband counseled. “Warren is 34, after all.”

“Someone has to find out what changes he’s looking for that can’t take place without his getting involved in the Panther Party.”

Betty’s husband promised to talk to Warren. Betty patrolled the house tucking in children and making lists from Julia Child’s cookbook and came back to bed more agitated.

“But Uncle is a believer! He’s loyal in the extreme. If my brother believes in Mother’s Milk, he will give his full support to Mother’s Milk. I will never forgive myself if—”

But Ernest Osborne, who had an early meeting with the black faculty next morning, was asleep.

March. Warren Kimbro’s first loyalty test.

National headquarters sent word the Bridgeport chapter had no official Panthers except its director, Jose Gonzales, and he was under suspicion. “If you see Gonzales, hold him,” Warren was ordered.

Amateurs … as far as Betty Osborne could see there wasn’t a sophisticated revolutionary in the lot. She was comforted too by learning her brother’s application to the party would take at least six months to be approved.

“So much of it is ego and sex.” Betty was now trying to comfort her brother’s wife, Sylvia. “If Ernie grew a beard and walked out on Yale Green shouting All Power to the People and Mother-effer, he’d have those suburban housewives following him like the Pied Piper.”

“… From the Oakland perspective, the East Coast brothers looked like loud-mouthed rubes. Central Committee wanted a purge …”

Warren’s wife, however, cared less and less for the people hanging around her apartment. She went to Legal Aid. There was talk of divorce, which brought Betty Osborne back to the boiling point.

She intended to give conciliatory advice. But when she finally got a call through to her brother, the talk quickly disintegrated into the insults born of fear.

“How the hell do you even know they’re Panthers?” Betty demanded.

“I know.”

“Uncle, any dude can put on black leather and come up from Bridgeport with a big line.”

Warren said he had been frustrated too long. His life was going nowhere. He wanted to see some real changes in New Haven for a change.

“You’re grasping at the first thing to come along!” Betty countered. “Look at all you have to lose, your wife and kids …” letting this penetrate … “listen to me! Has the Hag ever given you phony advice?” Warren’s pet name for his outspoken sister was the Hag, but now her words were nothing but a trickle in his ears.

Betty laid on him her trump card.

“They’ll put you out there to do all kinds of dirt and then you watch, Uncle—they’ll pull out on you the minute the —- comes down!”

“Okay, Hag.” Warren gave a final, affectionate laugh. “I’ll watch my step.”

April. Warren Kimbro’s apartment at 365 Orchard Street had become Panther headquarters in Connecticut. As a setting it didn’t seem to fit. This was no slum basement shared by derelicts and vermin … not remotely similar to the old Carpenter-Gothic frame houses on the other side of Orchard Street where eccentric roomers sat rocking in dark glasses and baseball caps, waiting to die.

Warren lived in an attached townhouse. Modern motor-inn style, it was one of the low-middle-income co-ops that drove out the poor during New Haven’s romance with the bulldozer. Zinnias in its family gardens. Children playing tag around the outdoor gallery hung over its parking garage. Lots of children.

But now Warren Kimbro was in all the way—his home, his salary, his life and his agonized wife, who decided the lesser of two evils would be to stay there with the children and cope.

At this time, on a national level, Stokely Carmichael broke completely with the Panther Party. Tears were few for the former leader of the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee. He had been given a top leadership position in the BPP as a tribute, but not without reluctance on the part of founders Eldridge Cleaver and Huey Newton. The conflict was over whether or not to unite in the revolutionary struggle with white radicals. The Panther Party was committed to this unity. Other black power organizations such as SNCC and US, the West Coast black nationalist faction, were dead set against it, requiring strict black separatism. This the Panthers condemned as racist. Months of feuding between Stokely and Eldridge exposed the growing contempt of younger militants for Stokely’s attitude. Stokely was ultimately branded a hangover hero with a now irrelevant black nationalist hang-up.

George Sams, a volatile Panther stalwart, was relieved as Stokely’s bodyguard. It is not known for certain, but Sams may have cried.

Stokely, maintaining a distant dignity in Guinea, sent his wife to meet the press at Kennedy Airport with a letter in which he warned against the high authoritarianism of the Panthers:

… The present tactics the party is using to coerce everyone to submit to its authority … the demand for loyal and unquestioning followers rather than critical colleagues … will lead the BPP to become, at worst, a tool of racist imperialists used against the black masses …

Ericka Huggins, meanwhile, was gaining a reputation among kids in the Liberation Children’s School on Lamberton Street. Children were given breakfast at the Legion Hall and ferried to a former Episcopal church. A few black and white Yalies taught them in a relaxed atmosphere.

School policy was not to force any political message on the children. They came to school with their parents’ politics … and, as another teacher said, “Parents weren’t against the Panthers, but they weren’t out selling Panther newspapers either.”

“… A local newspaperman interviewed the Panthers about their programs while upstairs Rackley lay spreadeagled and naked …”

May. The Bridgeport Panther chapter folded. It seems Jose Gonzales, the director, had made off with the chapter treasury. New York was also in bad trouble with 21 Panthers arrested and charged with complicity in a bomb plot. National officials Landon Williams and Rory Hithe were dispatched from headquarters in Oakland “to straighten out the party on the East Coast.”

Every political organization has its regional prejudices. And from the Oakland perspective, these East Coast brothers running around calling themselves Panthers must have looked like a bunch of loud-mouthed, chicken-tailed rubes. The Central Committee wanted a purge. Informers had to be cleaned out.

Connecticut was the first concern of Hithe and Williams. The New Haven chapter, less than four months old, was warned by Ericka that Central Committee people were coming. She confirmed the official status of George Sams, Rory Hithe and Landon Williams. Williams would be in over-all charge.

On May 14, eve of the purge, Landon Williams made a statement to a meeting of Connecticut revolutionaries, the irony of which only struck home much later.

“There are no Panthers in Connecticut except Ericka,” he said.

As far as Warren Kimbro knew, the plan for the weekend was to picket an Adam Clayton Powell rally in Hartford. From there on he would take orders. But one does not have to be a Panther to catch—or be caught for—Panthermania.

Saturday, May 17. Confusion. Meetings. Vague orders being dispatched. Doors slamming and people leaving for Hartford. The way the front and back doors were flapping and people knocking each other down to get in and out of Kimbro’s house, it might have been Stop and Shop.

Warren Kimbro and George Edwards, another aspiring Panther, were the only New Haveners there. Ericka Huggins was the only accredited Connecticut Panther present. Yet through Warren’s apartment during that weekend there passed, on faith, more than a dozen near-strangers from other cities.

The action began when Landon Williams and Rory Hithe drove up with George Sams and a young, square, semi-literate kid named Alex Rackley, an instructor in martial arts from the New York Panther chapter. They had picked him up on the streets of New York, he thought, to provide extra security for the impending visit of Bobby Seale. Rackley figured he was in for a thrill of his life. He was accustomed to sticking out like a sore thumb, the dumbest and weakest link in New York Panther organization. For once he was running with the big-time dudes. But Rackley was not long in the paranoid Panther milieu in New Haven before he was accused of being an informer.

Dapper Lonnie McLucas checked in with pretty Peggy Hudgins, survivors from the Bridgeport chapter. More girls arrived, incredible female traffic passing the neighbor’s zinnias and baffled stares. Eager Loretta Luckes, and Frances Carter with her poised, motherly air … followed by the irresistible Rose Marie Smith with baby hair still bunched tight to her scalp. All disappeared into the motel-modern interior of Apartment 3-B.

The reason for everyone’s being on his best revolutionary behavior was that Chief of Staff David Hilliard was in town. And Chairman Bobby Seale was arriving to deliver a speech at Yale on Monday.

“Rackley should be kept overnight,” Kimbro and Ericka were told. “Send George Edwards out for hamburgers. But watch him. He might make a call from the drugstore.”

Now there was a puzzle. Among members of the Yale-affiliated Black Arts Theater group, all George Edwards was famous for was being a fine actor. Unforgettable in a turban and backed up by Gregorian chant, he had played the bedeviled George in Who’s Afraid of Virginia Woolf? Suddenly it appeared that George Edwards, too, might be cast in the role of informer.

Sunday, May 18. Two girls barely past puberty strayed in with vacant eyes and cardboard suitcases.

“Lonnie’s friends from Bridgeport,” somebody said.

Ericka and George Sams ordered one child to the kitchen to boil water. The second stray child was ordered to sleep with the suspect Rackley to get information out of him. The air pulsed with cross-currents of suspicion. George Sams had just put Rackley in the cellar. He would direct an interrogation of Rackley and record the proceedings on tape for national headquarters.

George Sams had learned party rules. Individualism on the Body Is Counter-Revolutionary. Meaning sex on party time is a no-no. But this didn’t inhibit shy, romantic but exuberant Lonnie McLucas nor the exuberant Peggy Hudgins. They had fallen in love at first sight in February. Lonnie was at pains to prove his mettle to Peggy, which under the circumstances would not be easy. Lonnie and Warren Kimbro and George Edwards were low men on the totem pole. While the big shots waltzed in and out to Hartford, dropping orders, these three were left home with the girls to mind Rackley.

“Call Trailways Bus Company,” came a surprise directive from Sams to Kimbro. “Find out what it costs to go down to New York.” Alone briefly with his victim, Sams considered turning him loose. But Rackley complained he couldn’t find a jacket. A jacket, what the hell kind of excuse was that! Sams ordered the victim taken from the cellar to an upstairs bedroom, where the interrogation resumed in earnest.

George Sams projects the air of a streetcorner hipster in early fifties shoulder pads. There’s no mistaking the old diddy-bop walk … that sinking-down-in-the-ankles walk which sets the chin to sliding in and out and gives the over-all effect of a man moving on ball bearings. On him the Afro never quite came off. It looked more like a pompadour. Raised poor in the South by his father, George was three times shunted into mental institutions, once labeled a “dangerous mental defective.”

“… They needed more than a whimpering, tortured halfwit to build a purge on …”

George has been expelled twice by the Panthers. Or once. Depending on which day one asks.

“It was only once I was put out of the party, when I was expelled out by Chairman Bobby Seale,” Sams later decided under cross-examination. “But I was reinstated by Stokely Carmichael.”

Alex Rackley had claimed he could not read. But Sunday morning Sams found him lying in bed with Selected Military Writings of Mao Tse-tung. Outrageous! Ericka was called in.

“So then the brother [Rackley] got some discipline in the area of the nose and mouth,” said Mrs. Huggins, describing the scene while Sams tape-recorded her voice, “and the brother began to show cowardly tendencies, began to whimper and moan. We began to realize how phony he was and that he was either an extreme fool or a pig. So we began to ask questions with a little coercive force and the answers came after a few buckets of hot water. We found out that he was an informer.”

Monday, May 19. The day began badly. Sobbing and choking on the upstairs bed, Rackley pulled out names. “Steve … Janet … Jack Bright … Akbar … Lonnie Epps … I heard a conversation between Janet Serno and Inspector Hill of the 28th Precinct …” At one point George Sams paused to give his victim a cold shower. It went like that into Tuesday. This scramble-minded boy sang an operetta out of the telephone book, longing to impress his inquisitors, while they copied every police interrogation technique they knew in the interest of their own survival.

Kimbro and McLucas got orders from Williams and Hithe. “Get Rackley ready to be taken away. Find a car. Call Hartford and tell those dudes to bring down some political power” (meaning—off the phone—guns). The officials left and confusion resumed.

A local newspaperman arrived that afternoon to interview the Panthers “about your different programs around New Haven.” Chatty … a few Panthers doing a living room interview around a coffee table in which a rifle was hidden … while Alex Rackley lay spreadeagled and naked on the upstairs bed, alternately being scalded, bathed and recorded for headquarters.

Hithe returned during the interview; Williams followed. About now these two officials sent to straighten out the East Coast began to lose their grip.

Fortunately they were not around when the Hugginses, John’s parents, unexpectedly drove by. They hadn’t seen Ericka for more than a week. They were out searching for their granddaughter Mai.

“We have some baby clothes …” But Ericka had already left Orchard Street.

Alex Rackley was improving. He even fingered New York State Chairman David Brothers and his secretary, Rosemary, for telling tales on the New York 21 before their arrest.

“Chairman Brothers and them was saying on the thing—like Alexander’s, Macy’s and Bloomingdale and Botanical Gardens—that all this added up to the thing that was on the indictment of the 21 brothers.”

His inquisitors seemed to like the Chairman Brothers story, as people are always delighted by imagining corruption in the highest places. Rackley built on it. He accused Chairman Brothers of being sympathetic to Ron Karenga, the California leader of the US faction who killed John Huggins.

That must have gotten to Ericka.

Rackley droned on, barely coherent, until something in this lunatic scene hit Lonnie McLucas funny.

“Lumumba Shakur,” offered the young man on the bed.

“That’s no name!” McLucas blurted.

But the game had gone too far and big shots were in town and the locals on Orchard Street presumably needed more to build a purge on than a whimpering, tortured halfwit. Landon Williams criticized the insecure way Rackley was tied. “Use coat hangers.” His followers fashioned a wire noose for Rackley’s neck.

Hopefully this evidence of business-like interrogation would impress David Hilliard. Williams brought him to Orchard Street Monday evening before Bobby Seale’s speech (according to Kimbro’s testimony). The captive’s voice was heard, rising out of his humiliation on the upstairs bed.

“Is Chairman Bobby going to have me killed?”

“I’m not concerned with you,” Chief of Staff Hilliard scoffed (according to testimony). “You’re a pig.”

The important people then drove off with Ericka Huggins to her house, where Bobby Seale was to arrive. Warren Kimbro remembers being told to find another apartment where Chairman Seale could later speak to all Panthers from Connecticut.

Things grow murkier from there on because nobody wants to remember aloud exactly what Chairman Seale did and said before leaving New Haven. Mr. and Mrs. Huggins stopped by Ericka’s apartment, still searching for the baby. Startled by Seale’s presence, Mr. Huggins hid the pain behind his face and asked one question.

“What happened to the men who killed my son?”

“They’re in jail,” answered Seale.

Another little girl was lost that evening, during Bobby Seale’s speech before Yale’s Black Ensemble Theater Company.

“Diane Toney is missing,” Chairman Seale announced. Most of the Panthers went off in search of the missing child and somehow the Chairman’s meeting with the Connecticut rank and file never took place.

Warren Kimbro went home from the event to count receipts. He fell asleep after midnight. When Ericka woke him on the morning of May 20, she told him that Chairman Seale had stopped by Orchard Street to use the phone and then left town. They hadn’t wanted to wake Kimbro. (According to Kimbro’s testimony.)

George Sams later gave a different account of those early morning hours: He and Kimbro, Rory Hithe and Landon Williams were all present in the upstairs bedroom, Sams insists, when Alex Rackley was presented to Chairman Seale. What was to be done with him? “What do you do with a pig?” Sams recounts the answer from Seale. “Off him.”

By Chairman Seale’s own account, he did stop at Kimbro’s apartment to make a phone call. But of the small-potatoes interrogation upstairs he knew nothing. He claims he met George Sams only once, in 1968. Had he known of the brutal scene, he would have expelled the guilty members. But according to Seale, the hierarchy of the Panther Party can’t be expected to have time for policing the rank and file.

“I’m just the Chairman,” says Seale. “I don’t pay attention to everyone.”

Tuesday and Wednesday. Orders had not been carried out. Rackley was not dressed to be taken away. No guns from Hartford. George Edwards—”Get Edwards over here; we can take care of him at the same time”—was conspicuous by his absence when Landon Williams and Rory Hithe returned to Orchard Street Tuesday morning. Warren Kimbro never did make the call to Edwards. All the harassed officials could manage was to reprimand Lonnie McLucas for pulling a blank on help from Hartford.

New orders started flying. “Put Kimbro on the phone to Hartford. Sams and the girls go up and cut Rackley loose. Get the rifle downstairs. Get dressed in dark clothes. And put your asses in gear!”

Was this any way to run a political purge? But the voicing of doubts would have been a dangerous, counter-revolutionary act.

The appointed disciples noticed something curious about Rackley as they led their shaky captive out the kitchen to a waiting car Tuesday night. The coathanger around his neck stuck out. Kimbro threw a green bush jacket over Rackley’s shoulders to hide the hanger. (In the pocket was a phone message taken by Ericka Huggins for Bobby Seale which began: Don’t Come to Oregon. That little clue was discovered later, under the dead body.)

“Power to the People!”

Landon Williams managed that last battle cheer for his bumbling disciples, and shoved a .45 through the car window to George Sams. Sams lit up a joint. Kimbro climbed into the front seat and Lonnie McLucas, as was his habit, said, “Right on.”

On the way to his death, young Rackley warned George Sams not to smoke pot while driving. “The police might see you,” Rackley said.

At the edge of a Middlefield swamp off Route 147, a boggy no-man’s land near the Powder Hill ski area, Lonnie McLucas stopped the car. He flipped up the hood to suggest engine trouble. With Rackley reluctantly leading, the four men filed into the swamp.

“Got a boat waitin’ for you in there,” Sams said, encouragingly.

The pathetically naive figure of Alex Rackley stared into blind midnight darkness. He shifted from one foot to the other. The ridiculous costume hastily assembled for him and tied with a rope around his waist hung off his blistered skin. He was barefoot.

“You kin take the boat to New York or Florida or anywhere, but don’t you never come back,” Sams said, “or Williams’ll kill me.”

But Rackley was afraid to go barefoot into the swamp. He said he was afraid of snakes.

“Off him,” Sams finally said. He laid the .45 in Warren Kimbro’s hand and Kimbro walked Rackley a little way into the swamp and put a bullet through his head.

“… We’re not big shots,” George Sams said, discovering a truth. “We could be killed …”

Lonnie McLucas had this crazy unrevolutionary picture running through his mind … the picture of his sweetheart, Peggy Hudgins, crying as he drove off. He had told her they were driving Rackley to the bus station. Now the warm gun returned by Kimbro was placed in Lonnie’s hand by Sams and the last order came down.

“Go in there and finish him off.”

Lonnie McLucas slogged over the marsh floor until his foot hit a body sprawled in the murk. He left a second bullet in Rackley’s chest.

“We may have to make a run for it if trouble arises,” Sams warned on the getaway drive. Suddenly the bottom was dropping out of his voice. The lonely and hideous truth of “political assassination”—when left to the lumpenproletariat who cannot afford the simplest social bonds in their struggle to survive at one another’s expense—fell out of George Sams’ mouth.

“We’re not big shots. We could be killed.”

His words put a freeze on the bad air between Sams and his silent accomplices. Then the nervous diddy-bop militant threw six live shells from the .45 out the car window. This enabled Sams to boast back at headquarters: “We shot him eight or nine times.”

Aftermath.

Fishermen discovered Rackley the next day. The call from Connecticut State Troopers hit New Haven police headquarters late Wednesday afternoon. The body of a dead Negro male has been discovered in a marshland near Middlefield. No great surprise. Police later admitted they knew someone was being held by the Panthers on Orchard Street.

Chief of Police James Ahern immediately met with a young lady described as a “confidential and reliable informant whom [they] had known for a period of ten years.” The young lady, “closely associated with the Black Panther movement in New Haven,” was shown Polaroid photographs of the mutilated body.

“That’s Brother Alex,” she nodded. This unidentified informant was only the first of many to sing a willing and sordid ballad—dedicated to personal survival—of the events they had witnessed on Orchard Street.

Shortly after midnight on Thursday, a heavily armed team of uniformed and plainclothes officers smashed their way into Warren Kimbro’s townhouse without a search warrant. They knew exactly where to look for everything. Exactly the drawer, for example, in which to find a stash of pot. Handcuffs were ready for Warren and five girls found there, including Ericka Huggins.

Sirens ripped through the New Haven night. Relatives frantically phoned the precinct. Attorneys were routed from bed. But everyone was barred from the stationhouse for 24 hours.

A handsome, agitated young black man tried everything he could think of to get past the detective bureau.

“I want to get in and investigate which party members have been arrested.”

“Identify yourself,” a detective demanded.

“Lonnie McLucas,” the young man said, a breath short of surrendering.

The detectives—incredible—sent him away. Lonnie drifted to Hartford, then to Baltimore and Jersey City and finally, half-heartedly, he set out for California to make a personal report to the party leadership. After that he would try again to turn himself in.

Cockiness quickly shook out of the eight captured bodies as they were shunted into interrogation rooms. Their faces, puffy with fatigue and the pinched frightened eyes of caught children, were not seen until the next afternoon. Police had tipped off the local paper. Their faces were strung across the New Haven Register under a banner headline: 8 PANTHERS HELD IN MURDER PLOT.

They were given one-name identities: Carter. Smith. Wilson. Edwards. Hudgins. Kimbro. Huggins. Francis. The two stray girl children from Bridgeport, Wilson and Francis, talked a scared blue streak and were released. Their tapes were labeled Juvenile A and Juvenile B. That was the last time they were seen around New Haven.

“How the hell were they going to be revolutionaries!” howled Betty Kimbro Osborne. Denied admittance to the precinct to see her brother, she had to wait for the next afternoon’s paper for basic facts—such as who had helped who to kill whom.

“What kind of disciplined revolutionaries have things so goddamned loose as to get involved in an offing with women and children—” sobs of outrage choked off Betty’s first words.

But the one prisoner who continued through the next few weeks to exude a passionate confidence was Warren Kimbro. The party, he insisted, would take care of everything.

Sobs dried quickly in Betty Osborne’s throat. The parched fury stayed and bitter gravel began to form deep in her stomach. Sickened by the naiveté that had been found in a local idealist and twisted into this grotesque outcome—which she had foreseen—Betty tried to find explanation. She visited her brother regularly. Clipped the papers compulsively. New names kept coming up, pregnant girls and mental midgets she had never heard of, the people who gave orders and the people who talked to police. The bitter gravel rose in Betty and each night she came home to spill it out.

“Everybody is worried about the conspiracy J. Edgar Hoover is pulling. I’m worried about the conspiracy that goddamn party is pulling against my brother! They took a local dude with leadership ability, a person who was well-established in the community, and he was used. He gave his life to the party. But since everybody got picked up there hasn’t been a mention about Warren. He hasn’t been a Panther since! It’s all Bobby Seale and Ericka Huggins. I really blame myself for what happened, for not nagging more …”

“… How could a murder, with two confessions in hand, serve political ends? …”

The systematic dismantling of the Black Panther Party began in New Haven. From Warren Kimbro’s apartment on Orchard Street, where white America detected a deadly virus, the national stool-pigeon network was turned on and anti-Panther vaccine went out. Federal agents raided chapters in Washington, D.C., Salt Lake City, Denver and Chicago, looking for Sams, McLucas, Williams and Hithe.

In June, Lonnie McLucas, out of bread and hope in Salt Lake City, walked into a Western Union office. He was hoping to find a money order from party headquarters. FBI agents took him into custody instead. He asked to give a statement. It was noted that the young fugitive spoke almost with relief:

“I became disillusioned with the party because of the violence … wanted to quit … afraid to quit because I had learned too much … I was afraid I might be killed.” Young Lonnie filled in the picture of Bobby Seale being told in Ericka Huggins’ kitchen about the suspected informer held on Orchard Street.

In early August George Sams heard in Canada that Toronto police were coming for him. He mentioned to a local officer that he was afraid of being killed in connection with a political assassination in New Haven. Then he sent for the FBI.

Three days later Bobby Seale was arrested in Berkeley, California, on a fugitive warrant and the implicating word of George Sams. The day before, David Hilliard had been arrested. By the end of August the raids that snowballed out of Orchard Street had crippled every national party leader. The Panthers were in jail, in exile or in coffins.

Fall, 1969. Suddenly Warren Kimbro’s letters to his sister no longer bore the stock signature: Power to the People.

All summer he had waited in Montville State Correctional Center for a word from the Panthers. No word came. From euphoria he languished into an emotional coma … jumpy, paranoid … stopped eating … dropped twenty pounds. He asked Betty to bring a book on her next visit: Karl Menninger’s The Crime of Punishment. From prison authorities he requested Catholic literature. Raised a Catholic, he had dropped from the Church to embrace the Panther creed. Now, it seemed, a large abandoned evangelical void inside Warren Kimbro longed to be filled.

His letters began to come home signed simply—

Love, Uncle

January, 1970. Warren Kimbro’s brother on the Dade County police force had called Betty Osborne from Florida in December.

“What’s going on up there?”

“Your law enforcement buddies are messing up over black people again,” Betty said, having no love for police in any form, including brotherly.

“Are you a Panther?” her older brother demanded.

“Isn’t everybody?” Betty was flippant without thinking.

Brother didn’t like it. He insisted Betty give Warren Kimbro his address. She reluctantly passed it on. Warren did write and when his brother, the Florida cop, visited Montville, Warren said things were clearer to him now.

“When I made my first statement I was only concerned with what I had done, that I had made a fool of myself in shooting Rackley. I wasn’t thinking about what anybody else had done.” (From Warren’s testimony.)

“Now do what you were raised to do,” Warren’s brother pressed him.

On January 16 the abandoned “Panther”—who had never officially become a Panther—changed his plea from innocent to guilty of second-degree murder. The mandatory sentence in Connecticut for that crime is life imprisonment. Warren later agreed to testify for the state. This brought the wrath of the Panthers down on him, the inevitable charges of “Pig!” and “Traitor!” But Warren Kimbro had very little to gain by helping the state’s case. After sentencing, twenty years must elapse before he can apply for parole.

Chairman Seale did not appear in New Haven until spring. He had been detained, and had been made even more of a rallying point, by the Chicago conspiracy trial. But on May Day, almost a year after the shooting, the feds finally brought Seale, Mr. Publicity, to town. Cast in place, the opening in New Haven was hailed at last by the New York Times for the political theater it was:

SEALE IS THE MAIN DRAWING CARD FOR PANTHER RALLY IN NEW HAVEN

May Day weekend. Excitement built for six weeks. Bread and circuses were being planned all over Yale, in celebration of the town’s first Black Panther rally. A handful of Panthers had planned the rally to demonstrate local black support for the New Haven defendants. How could a murder case, with two confessions already on the books, serve anyone’s political ends? we puzzled.

We stopped wondering a week before the rally. One had to take sides. The propagandist wisdom on one side—students, radical liberals, and racist-fighting faculty—was churned out and committed to memory like a page from Dick and Jane: the Panthers were being railroaded into a trial for the murder of one police informer, organized by another police informer, and pinned on Bobby Seale. Therefore, the killing was justified, police were the criminals, and the trial was just another trick bag into which black people are constantly being put.

Thousands of white ralliers and newsmen (including us) accepted this line of reasoning on baby faith. A curious lapse in moral linkage was buried in our brains under the section marked “Guilt.”

“…’A jury of twelve elderly, uptight conservative blacks could be bad news’…”

A week before the rally we walked into the black community, photographer David Parks and I. We had our baby ears pinned back.

Over at Yale Medical Center, working around the clock to monitor rumors, a leader of the Black Coalition scowled at the radio. Reports of an impending clash between student ralliers and police peppered the air. “Hell, no, I don’t want them to bomb everything,” the black leader snapped. “We haven’t had a piece of it yet.”

The Coalition had released a memo through their newspaper, The Crow, spelling out what kind of welcome they held for visiting white Panther lovers:

They cry “right on” but their purpose is not our purpose and their goals are not our goals. The truth in New Haven, as in most of the country, is that the white radical, by frantically and selfishly seeking his personal psychological release, is sharing in the total white conspiracy of denial against black people.

Doug Miranda, acting captain of the New Haven Panther Party, and Big Man, another stalwart, apparently brought in to help bolster decimated Panther ranks, had been around to the black high schools all week. Enthralled, the kids promised to strike and march in a body to the rally. That set off an alarm which spread like night sirens through the black grapevine. Mothers went to the schools fighting mad and made their position vis-à-vis the Panther plan indisputably clear.

“No black kids are going downtown. No black parents are going downtown. Furthermore, here is where the line is drawn between the black community and the Green.”

Arnold Markle, the state prosecuting attorney, wasn’t sure who posed the greater threat, visiting Weathermen or local ethnics, who seemed to have bought up every gun in the state. For a little help on the Panther end, Markle went straight to Montville and had a chat with Chairman Bobby Seale.

“I want that goddamned Doug Miranda sent away,” Markle said.

“Power to the People,” Chairman Seale said.

“Look, Bobby, let’s understand, you control your people, the Panther followers. I can control my people, the cops. I want those kids to go to school. You get Miranda out of their hair.”

“Tell you the truth,” Seale said (according to Markle), “I think Miranda’s nuts, too.”

From wherever the control came, the children of the black community did not appear at the rally. Thirteen thousand overwhelmingly white college students did.

Quake! Panic! Connecticut in a funk! Four thousand men of the 82nd Airborne and 2nd Marines from bases in surrounding states came by plane to await the holocaust. Brown trucks rolled into the city and spilled National Guardsmen on the streets. Long mute lines of little boys in weekend soldier uniforms hid behind unsheathed bayonets, forbidden to speak to the passing rabble. Finally, on the afternoon of the rally, the Guardsmen wedged into York Street, one block from Yale Green. Come and get it, baby! President Nixon was preoccupied at the time with the invasion of Cambodia. But while Attorney General John Mitchell and Governor John Dempsey and Senator Thomas Dodd helped to prepare the climate for violence, Yale President Kingman Brewster watered the fuse. The university family came together in hundreds of meetings. Striking students and black faculty aired their bitternesses, discussed ways to monitor the upcoming trial and generally slugged out the more obvious aspects of racism in the spirit of dinner-table debate. Speaking to his faculty Kingman Brewster made his famous statement:

“I am appalled and ashamed that things should have come to such a pass that I am skeptical of the ability of black revolutionaries to achieve a fair trial anywhere in the United States.”

May Day opened, flowery. And opened and opened in the tingling sun like the magnolia blossoms in Branford College courtyard. Welcomes everywhere. Long tables were spread with brown rice and Familia. Ripe-bosomed co-eds dished up a soul picnic for the incoming bedouins of the Woodstock nation.

Meanwhile, super-efficient student marshals patroled the campus, giving it the prepared aura of a big-city emergency room. There were rock bands. And signs. Signs to the People’s First Aid Station. Signs to the john. Signs everywhere bearing the commandment: Help the Panthers Keep the Peace.

On Saturday afternoon people covered Yale Green like crocuses, bathing in May sun. The speechmakers worked hard. But the crowd was less combustible than convivial.

“In Huey Newton’s trial the first thing people wanted to know was the facts of the case. The hardest thing is to convince them the facts are irrelevant.” Tom Hayden’s words stunned the crowd to attention.

“The trial in New Haven is a trial of whether or not there is anything left in this country worth defending.” Visibly pained by having to walk a rhetorical tightrope over the dubious heads of his Panther hosts, Hayden went on to make great promises on behalf of his sprouting white revolutionary crocuses.

“We have to make an all-out effort starting this summer in every town around, every factory and college, and turn the whole New England area into a giant political education class—the last political education class they will have.” He challenged strike-bound students to form White Panther brigades.

Abbie Hoffman interchangeably shilled grass, revolution and release from Whitemiddleclass Paralysis.

… “the most oppressed people in America are white middle-class youth … my brother is a Chinese peasant and my enemy is Richard M. Nixon”—a pause here for the obligatory rally commercial: Eff Nixon! Eff Nixon! The crowd obediently stood to do the chorus for Abbie’s one-minute Nixon spot. He rewarded them: “We ain’t never, never, never gonna grow up. We will always be adolescents … Eff rationality … We got the adults scared to eff anymore ‘cause they know they’re gonna have long-haired babies!”

Abbie barely remembered, coming down from his rant, to put in a plug for the Panthers, whose rally it purportedly was. He set up the crowd like tenpins and bowled them over: Free Bobby! Free Ericka!

Doug Miranda picked it up and went for a strike. The young Panther from Boston prophesied: “We just may come back with a half a million people and liberate New England!”

Stirring … yet, immediately after the rally, the movement lost focus. A handful of political groupies—four dozen whites from schools of paperback Marxism and a few black students from Harvard and Cornell—massed across the street from the local jail. Begging for a group snort of pepper gas. A lineup of police, under the walkie-talkie command of Chief Ahern, stood with hardware on hip. Expletives flew. A block away National Guardsmen stood in ready phalanxes.

Suddenly—weird—along came these infuriated marshals from the local black community. Shouting “When you leave, we’ve got to live here!” they found themselves fighting across an iron fence against black students. Fighting black Harvard students—dream kids, for Godsake! Painful.

Walt Johnson and other black Yale students shrank in disgust from the spectacle of white radicals running loose across the Green.

“Credit-card revolutionaries,” Walt Johnson pronounced them. “In July they’ll be hitching to California on Carte Blanche. In August they’ll be sitting in Allied Chemical discussing the great rally they pulled off in May.”

The Panthers found themselves in the middle. Literally. The cops were behind them and the white militants were on the other side of the fence.

Over a milkyface boy in a Columbia T-shirt, who was viciously brandishing a broom handle, rose the imposing hulk of an aide to Doug Miranda.

“I want to kill a pig,” whined the boy with the broom handle.

“What you got in your pocket, a yo-yo?” hollered the Panther. “You think those cops are packing plastic bullets? Who do you think they see first? The black faces, got it kid? All black faces look alike. Panther faces. What you think I got in my pocket, kid?”

Milkyface shrank into his Columbia T-shirt. The Panther slapped a hand on his pocket in a fake draw.

“I got a gun!”

Milkyface dropped his broom handle and ran. The Panther turned with a smile. For the spectators he pulled out his empty pocket lining.

“This is not the time!” the Panther hosts hollered through bullhorns and sound trucks all over town.

Unforgettable. A bizarre coalition of Panthers, black residents and Kingman Brewster, leading Yale’s liberal elite, had saved the day. The Yale rally went down as a good political festival, just as Woodstock was the only good rock festival.

“… If the Panther Party determines to survive at all costs, they may copy the Mafia. To belong one may have to kill a cop …”

July. Summer came but the people’s army did not. New Haven’s adult black community zeroed in on other, more urgent trials: how to scrape through the recession and send their children back to school. The rumor pump went dry.

Scrawny rallies staged across the street from Superior Courthouse scarcely made TV dinner news. Abbie Hoffman presided over one. He was thrown to the ground with a fearsome karate block by a girl from the resident Women’s Collective.

Indeed, the only riot last summer erupted at Cozy Beach in East Haven. Italian against Italian in a three-day fire-setting melee over July Fourth. Embarrassing! Six men were arrested. But the outcome of these arrests was somehow never reported in the New Haven Register.

Confronting the Panther trial, however, New Haven’s legal family was haunted by Chicago’s experience with an antic conspiracy trial. As a state official sized up the New Haven situation last June: “We couldn’t get a death penalty on the Panther case if guilt was written in stone.”

First problem: how to select a jury of peers for black revolutionaries.

“Twelve elderly, uptight conservative blacks on a jury could be the worst news the Panthers ever had,” one officer of the court said. He was equally concerned with the prospect of sending one black juror back to the wrath of the ghetto. The problem is, many black residents of New Haven County are unregistered and therefore scantily represented on juror lists.

“So,” this observer guessed, “we’ll get a mixed jury and a political verdict. A compromise. If we can avoid another Fred Hampton situation, I think we can get this trial into focus.”

State’s Attorney Arnold Markle knew his town. A short, feisty man who speaks to the snap of his expandable watchband, he is anxiously liberal. Quick to admit his home state has one of the most unprogressive criminal codes in the nation, he instituted classes to educate police officers on the rights of the accused. He has worked hard to abolish the death penalty and liberalize narcotics laws. But he was determined to break the hold of Panthermania on his town.

“Sure, lots of Washington people would love to get their hands into this trial and make a name for themselves,” Markle said last spring, clamping down on a meerschaum. He paused to carve dead tobacco out of his pipe. “But I’m not about to let that happen. Or to let the defense get the bad press they want, to build a case of political persecution.”

Markle made good on his promise. He won a court order prohibiting “extra-judicial statements” by practically everybody connected with the trial, which considerably lowered the voice of the press.

The Trial. What had begun with the arrest of seven political infants and a resident idealist, having already unleashed incredible racial combustion across the nation, came finally to public view fourteen months later on. Now it was billed with all the really-big-show words in the indictment: Conspiracy to murder, kidnaping resulting in death, conspiracy to kidnap, and binding with intention to commit a crime.

Early local headlines did not improve the Panther image. Unfolding in newspapers dropped near the Dellwood Milk box each morning were such improbable images as:

LISTENED TO RECORDS, SMOKED POT AFTER SLAYING, SAYS KIMBRO

Stunned by bizarre testimony, New Haveners began to ask questions. Had this been the work of an efficient, nationally controlled paramilitary organization? Or was it simply Amateur Night in New Haven? Was Alex Rackley murdered by a chain of orders systematically handed down from the top? Or by nothing more than flailing egos of the rank and file in a fit of braggadocio?

It was hardly a proud moment for the Black Panther Party. Determined to protect Seale from a conspiracy rap, the party started out heaping abuse on George Sams as a police informer. But the Panthers had a hard time making anybody, including their own lawyers, believe it.

Was Rackley “iced” on the basis of casually dropped kitchen rhetoric by Chairman Seale? Or because George Sams was desperate to ingratiate himself with his old friend Stokely Carmichael so together they could take over the party (as the defense suggested)? Or, as the Panther newspaper had decided, because Sams was “a crazy boot-licking nigger” (“… Our diagnosis from the perspective of revolutionary psychiatry”)? Or because George Sams was simply a scared loser with an 83 IQ and a Swiss cheese brain who did not know what else to do?

Chairman Seale, advised of Warren Kimbro’s non-implicating testimony, rejoiced: “That puts the State up —-‘s creek, doesn’t it?”

But the party itself was ultimately moved to give a formal statement:

“The Black Panther Party has to stand in judgment [by] the people, because in that period of our party’s development, we allowed a maniac such as George Sams to come into our party.”

From the outset the New Haven trial was a political dud. But as an exhibition of the weaknesses inherent in any revolutionary organization, it was a very instructive trial indeed. The Black Panther Party here and across the nation faces two threats that have plagued counterparts throughout history:

(1) Rivalry for leadership. The transfer of power within an elected party is generally orderly, and slow. By nature the followers of a revolutionary group look to their most extreme members for leadership. As a more militant warrior emerges to catch the imagination of the cause, the old leadership is impugned, attacked as weak, either expelled or killed. With the transfer of power left to this turbulent process, a revolutionary party is always in danger of collapse through internal attack. The fact is, Black Panthers are scorned by most other black power groups, the Muslims in particular. Members of US, the black nationalist group, have killed Panthers. Eldridge Cleaver, in sanctuary in Algeria, is regarded most dubiously beyond the Panther faithful. Many militants go by this rule of thumb: No black fugitive gets out of the country. He is let out of the country.

(2) Informers and paranoia. Informers, traditionally the government’s most effective weapon against a rebellious party, serve two purposes. They provide information and induce the more devastating Infiltration Reflex. Innocents and hangers-on are suspected and tortured or killed in the manner of Alex Rackley.

As real and imagined informers build paranoia within the revolutionary cadre, the rebels begin turning one another in. Panthers have already testified against rival black militants. In New Haven they were being called upon to testify against one another.

There is one “revolutionary” organization in this country which has beaten the game. The Mafia doesn’t fool around with oaths and ideological loyalty. To belong you have to “make your bones.” Kill somebody. With that tie, the Mafia has you forever.

If the Black Panther party determines to survive at all costs, it may copy the Mafia technique. To belong, one may have to kill a cop.

The outcome of the New Haven Panther trial was determined by the first move in the chain of events leading to the trial.

“There are no Panthers in Connecticut except Ericka,” was the declaration from national headquarters. When Landon Williams and Rory Hithe were dispatched to purge the East Coast chapters, the chain of paranoia and internal mistrust was set in motion. Now in the Superior Courthouse of New Haven one year and three months later the rule was: every man for himself.

The defense of the New Haven eight was organized around this premise. This was not to be any New Wave conspiracy trial. Politics would not come before people. Defense attorney Theodore Koskoff, an officer of the National Trial Lawyers’ Association, set out to prove the system could work, even for a black revolutionary. Providing he dresses nice and plays it straight.

Each day the New Haven trial became less an exhibition of gross racism and political injustice, and more a Rabelaisian ballad of individual human desperation, fear and fallibility.

August. George Sams is doing a little singing downtown. In fact he is spilling the guts of the Black Panther Party all over the sidewalks of New Haven. The courtroom is small, orderly, square. Judge Harold Mulvey maintains a mild presence. There is no glare. Only a soft cosmetic whiteness that filters down from square frosted ceiling lights.

George Sams enters to testify, cool as tap shoes. In his navy blue blazer with padded shoulders he swings within inches of the defense table to outface Lonnie McLucas on his way to the stand. Lonnie is dressed to perfection. But Sams is improving every day.

“Who’s his tailor?” an attorney whispers to McLucas.

Now defense attorney Koskoff leads George Sams through an account of his travels over the three months following the murder. It’s a dizzying journey.

Koskoff: You left Orchard Street in a car with Landon Williams and Rory Hithe, drove to Kennedy Airport and boarded a shuttle. Where did you go then?

Sams: To Washington.

Koskoff: Landon wanted you to get records of Stokely Carmichael from a man named Jann in Washington, right?

Sams: Yes … and to get the names of contacts who were counter-revolutionary to the Panther Party so we could patrol the East Coast.

Koskoff: Did you get the records?

Sams: No.

Koskoff: Did you get Jann’s secretary?

Sams: No.

Koskoff: As a matter of fact, the Black Panther Party never trusted you, right?

Sams: No, they trusted me.

Koskoff: Didn’t you tell Sergeant DeRosa that Stokely Carmichael was trying to take over the party?

Sams: No . . .

While the jury is shuffled in and out of hearing range, the defense and prosecution haggle with George Sams over how many times he had been expelled by the party—according to his own previously recorded statement. Judge Mulvey decides to hear the tape in his private chambers. Koskoff returns to pursue the same line, hoping to establish Sams’ own mental imbalance as the singular motive for the murder. Meanwhile, he is demolishing the image of Panther Party discipline . . .

“… What really appeals about Panthers is summed up by Lonnie’s cousin: ‘Those cats do more travelin’ than rich folks!’…”

Koskoff: Weren’t you afraid to come back to New Haven without the records and to tell Landon you didn’t get them?

Sams: Yes, a little afraid.

It is established Sams hopped a taxi from Washington to New Jersey, then to “Mr. Krunstler’s” office [William Kunstler] in Manhattan, spent the night at Mr. Kunstler’s ladyfriend’s house in Greenwich Village, and then sped off for Chicago with Rory and Landon.

Koskoff: How’d you go this time?

Sams: Mustang. [Murmurs of approval, in spite of themselves, come from Panther supporters in the spectator section.]

Sams: We went to headquarters in Chicago to investigate the party policies and ideology.

Koskoff: How long did you stay in headquarters?

Sams: Twenty minutes.

Koskoff, the impresario, winds up in his starched collar to give this one everything he’s got:

It took you twenty minutes to investigate the party ideology?

Koskoff continues to lead Sams on his incredible journey . . .

Sams: That Sunday we pulled out and went to the Panther houses in Detroit. There was a lot of problems going on there. National hadn’t classified the chapter. We found a lot of renegades and counter-revolutionaries running around and it was clear to everybody there wasn’t a total Panther in Detroit.

Bizarre. By Sams’ account virtually every Panther chapter in America was suspect. Sams himself spent several days under house arrest in Chicago, then claims to have walked out with a .38 revolver one evening and passed, unrecognized, through a line of FBI agents surrounding the house. He fled to Canada disguised in a preacher’s suit.

Sams: I got my own place till I got captured. Somewhere ‘roun’ two and a half months later.

Koskoff: What were you doing in Canada?

Sams: Running.

Koskoff: How did you live?

Sams: People supported me. Some of them kids in SDS, the ones that split up over that Yugoslavia thing, and some people in the Communist Party— they was all arguing with each other and supportin’ me. Just a buncha liberals, you know.

The press section breaks up. Even the jurors snicker. The front line of Panther spectators is convulsed with laughter and the court, summarily, is recessed … Just a buncha liberals … Dynamite!

Recess. Lonnie’s cousin from Port Chester is stretching his legs on the Green. He is a tall, friendly looking man in his late twenties and the testimony has obviously knocked him out. Port Chester, he says apologetically, isn’t hip to the Panthers yet.

“Man, I had no idea how widespread and powerful the party is,” he says. He runs over the testimony from his point of view: George Sams hopping taxis to Jersey, jiving all over the country in planes and Mustangs, laying his hands on petty cash to go wherever he wants to go. What gets him, as it probably gets thousands of young men immobilized in dull jobs in dud towns—what really appeals about the Panther Party beyond its complicated political visions—is summed up in the final comment of Lonnie’s cousin:

“Those cats do more travelin’ than rich folks!”

Bread and Roses Coffeehouse.

Eyes shut behind plywood windows. The coffeehouse is closing tomorrow at midnight. Inside, the Movement is eating its last supper in New Haven. Desultory trial-watchers and stragglers from the collectives, which never pulled more than 200 people into New Haven at any one time, sit behind bowls of Chlodnik and Familia not saying much of anything.

“As usual,” confides a disillusioned summer radical, “the white revolutionaries are trying to do something good but they’re messing it up. Worst part is how cruel they are. They have no humanitarian feelings for anyone outside the movement.”

A tired, scholarly-looking young man drizzles into the booth beside us. He mentions he is from the Liberation School.

“Looks like you’re about to close up, too,” someone says.

“Tomorrow. Frustrated.”

“Why is that?”

“For the obvious reasons,” says the Liberation School worker. “We couldn’t organize the community. The workers wouldn’t listen to us. The trial’s a bore.”

Slabammmm! He blows in with chin whiskers and a loosely hung brown polo shirt. Packing a Nikon. A stranger, slapping back the old saloon door to set hearts afire and teeth once again on edge in the Bread and Roses Coffeehouse.

“I’m a photographer for Quicksilver Times,” he announces. “Just blew in from Washington.” He adjusts his mirror shades to glint us all straight in the eye.

The young man from New Haven’s Liberation School slides him a handbill, recounting the week’s trial proceedings. Quicksilver reads two, maybe three paragraphs.

“I’m speechless! How long has this mother trial been goin’ on? What’s the movement doing about this?” Quicksilver begins running it down for everybody. “Man, this is a really heavy city. You see a pig every ten seconds. And they got these green lights on their cars. This is an effing fascist state. I never seen a place that needs work so bad.”

The Liberation School man comes briefly to life.

“Are you familiar with New Haven’s Model City background? Did you know the conspiracy against the BPP started with the raid here?”

“I dig,” snaps Quicksilver. He lifts his polo shirt and flaps it around a little to cool himself off. While the Liberation School man goes into his political education speech, Quicksilver is rolling a spitball out of the trial news.

“Yeaaaah,” exhales Quicksilver. “I’m serious about staying in this city!” He leaps to his feet and hoists out the door, promising to return after he takes care of a little business.

Exactly ten minutes later, beaming, the Quicksilver Times photographer returns. “What a shot I got of Sams with a telephoto! Got him coming out of the courthouse, full face.”

“You gonna stay around?” tests the Liberation School man.

“Well, I just met a cat on the street who says DC is really getting together.”

“Yeah, and—”

“So maybe New Haven isn’t the place to work. DC needs me, man.”

The Liberation School veteran is already fading behind his bowl of Chlodnik.

“Hey,” Quicksilver brightens, “want me to send you a contact of the Sams shot?”

That was about the level of commitment and duration of conviction brought to bear by the People’s army on the liberation of New Haven last summer.

Lonnie McLucas smiled. The trial turned on that fact, which pretty much left revolutionary purists nothing to do but go home mad. Lonnie was every lawyer’s ideal defendant: bright-eyed, boyishly handsome, a little shy, an intelligent look about him and an irresistibly gentle manner. Furthermore, he was neat. Brass-buttoned - blazer neat. Stylish in his butterscotch shirt and print silk Christmas tie, impeccable down to his British ankle boots—but not, how shall one say, too showy.

They loved it. The white-pocketbook jury out of the Naugatuck Valley, fully assembled on August 11, was already in Lonnie’s pocket.

A folksy group out of 242 New Haven country electors examined on political and racial attitudes, these jurors—two black men, ten whites and one black woman alternate—were chosen primarily for their parochial attitudes. The Panthers were to be judged by people who seldom if ever read about racial matters, much less about Panthers. Lonnie smiled at each one who smiled back. He took notes.

It was pure theater! Lonnie McLucas was no sulky defendant. He was the director here, the LeRoi Jones of this Broadway-tryout town, swiveling in his director’s chair to size up actors, audience, reviewers. Jotting notes toward the final script polish. Attorney Koskoff was the producer. He wanted it played straight.

The jury spent 33 hours cooped up in a jury room measuring 14 by 15 feet. In their hands was the power to convict Lonnie McLucas for:

Kidnapping resulting in death; penalty death.

Conspiracy to kidnap; maximum penalty 30 years.

Binding with intent to commit a crime; maximum penalty 25 years.

Conspiracy to murder; maximum penalty 15 years.

Smiling rings of joy, Lonnie McLucas emerged from the courtroom into a jubilant crowd of supporters. Together they saluted the verdict with clenched fists. The young Panther had been acquitted of the first three charges and convicted of conspiracy to murder, which carried the lightest penalty.

“Lonnie McLucas is a very gentle man,” asserted one satisfied juror. “He’s no detriment to society. It’s his testimony that freed him, not his defense.” But what the juror really meant, the apparent key that unlocked a sympathetic response to this particular black revolutionary, was Lonnie’s delivery of his testimony.

Beyond the Trial

The Manson trial eclipsed New Haven through July. Our fickle media went for the traditional Hollywood-style sex-dope-murder trial. In early August New Haven paled again before accounts of the Marin County shootout. California again, but this time the California Panthers outdid themselves and surpassed most of the cherished desperadoes in American history for sheer theatrical-political virtuosity.

Jonathan Jackson and two armed companions literally stopped a trial dead. Taping a gun barrel to the judge’s head, they posed for their own photographer, liberated two prisoners and spun off in a van with their hostages through rabid police lines into a kamikaze bloodbath. What’s more, the guns were allegedly supplied by California’s pet liberal heroine, the beautiful, brilliant and persecuted UCLA teacher under the sizzling Afro—Angela Davis. At first she vanished into the Ten Most Wanted list. Now she languishes in a New York prison, fighting extradition. She had left California liberals dangling just as Eldridge Cleaver had done. And several weeks after the shootout, an agent was phoning around to sell Angela’s own story for $100,000. Exquisite!

The Panthers’ newspaper took New Haven by the hand and explained the uses of public homicide and progammatic suicide:

Every black person in this country must understand that which is happening in New Haven. Lonnie’s railroad is almost over. We said at the beginning of the trial that the pigs would hurriedly in an unconstitutional manner try to convict Lonnie. This has happened. That is the main reason why brothers like Jonathan Jackson (etc.) are and were justified in their assaults on the pig judge, the racist jurors and the fascist police of Marin County.

Revolutionary suicide [is] the new educational tool for the people!

Three thousand people poured forth from the Oakland community to salute the suicidal revolutionaries. Since John Huggins’ death, the recruiting potential of a Panther funeral had increased tenfold.

“The Black Panther Party will follow the example set by these revolutionaries,” prophesied Huey Newton in a riveting eulogy.

“There is a big difference between thirty million unarmed black people and thirty million black people armed to the teeth. The high tide of revolution is about to sweep the shores of America …”

Panthermania, of course, re-ignited New Haven. But the fires were quiet and hidden inside the children.

Bobby Seale and Ericka Huggins are scheduled to take the stand this week. It is almost two years since the Black Panther Party came to town, but the old burns, far from healed, will be uncovered again on the raw skin of black New Haven.

Warren Kimbro will almost certainly be called back to testify … Betty Kimbro Osborne will go back to sleeping fitfully on the living room couch, to keep her bitterness from poisoning her family, Ericka Huggins will bring back the apparition of John Huggins … his parents will look again at the baby, Mai. Tiny black girl-child in a berserk land—is she the orphan of a nearly burnt-out revolution? Is she the symbol of a hard-won pride? Or is she the promise of a future race war in which single human beings must be sacrificed for the collective political point?

We wait for an answer to come out of New Haven, the Model City.