On a damp, misty evening a few weeks ago, a small crowd had begun to gather at the corner of Decatur Street and Marcus Garvey Boulevard in Bedford-Stuyvesant. Cast in thick shadows by faulty streetlights, the group stood in front of the Bethany Baptist Church, collars turned against the chill, looking only at one another to avoid the eyes of the drunks and junkies who periodically stumbled by. It was the twenty-ninth anniversary of the assassination of Malcolm X, and most of the men and women waiting for the wooden church doors to open looked old enough to remember. Some wore African-style hats called co’ufees. Some wore buttons proclaiming I SUPPORT THE NATION or RESPECT THE BLACK WOMAN. One man carried a hand-lettered sign that read DUMP MOYNIHAN on one side and DUMP OWENS— Major Owens, the black Brooklyn congressman—on the other. A man from Queens in a gray double-breasted suit wore a scarf with the words U.S. SENATOR 1994 printed under a strikingly winsome picture of the Reverend Al Sharpton.

A rally was scheduled to start at 7:30, and as the time approached, the waiting crowd had grown into the hundreds. There were no wool caps, no hooded sweatshirts, no unlaced high-tops, no Timberland boots, no jackets with giant logos. This was not a crowd of people from the projects, the hard-core urban poor. And the majority carried no Afrocentric or political accessories. They were dressed as if they had just come from work, civil servants and lawyers, teachers and office temps, cabbies and beauticians, book-keepers and hospital workers—not the kind of crowd white people imagine at a rally for the Reverend Al Sharpton. But they had all come out on this dismal Monday evening to hear Sharpton announce that he would challenge Senator Daniel Patrick Moynihan in September’s Democratic primary. They had also come out to vent their rage at conditions in their neighborhoods, to show their unhappiness with black elected officials, and to proclaim their support for a new wave of insurgents now looking to purge and replace the established black leadership. And by the time the rally got under way, there were more than 1,000 people packed inside Bethany.

Sharpton had gathered half a dozen of black New York’s most contentious figures: activist and WWRL-radio personality Bob Law; lawyers and chronic race-baiters C. Vernon Mason and Alton Maddox; Adam Clayton Powell IV, movie-star-handsome Harlem city councilman and legatee of the most famous family name in the city’s black political history; Sergeant Eric Adams, the radical head of the Guardians, the black patrolmen’s association; and 28-year-old Conrad Muhammad, the leader of the Nation of Islam in New York.

Bob Law quickly set the tone for the raucous three-and-a-half-hour event. “This is the beginning of a movement. There must be a significant change in the leadership in our own community.” Without mentioning Owens, Charles Rangel, or any other member of the Old Guard, he repeatedly called black incumbents “punks” and “cowards,” men more concerned with advancing their own careers than with helping their communities. In a reference to the Louis Farrakhan—Khallid Muhammad controversy, Law charged, in his trained radio voice, that some black leaders didn’t take care of their own people because they were “too busy driving Miss Daisy and then checking with her to find out who they can support and who they must repudiate.” The crowd loved it.

“Teach!” screamed one woman in the back.

“Tell it, brother!” yelled a man from the balcony.

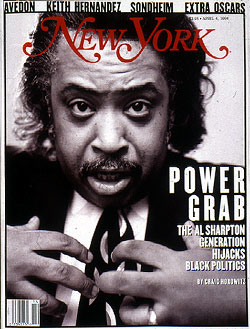

But this was Reverend Al’s night, and when he stepped to the podium, which was draped in kente cloth, the crowd exploded. Squeezing the moment, Sharpton quietly listened to the cheering. Dressed in the clothes of a serious political candidate—dark suit, gray shirt with white collar, red tie, black wing tips, and no medallion—he seemed content just to experience the scene. With the shine, the red highlights, and the processed curls of his neo—James Brown coif, he looked as if he had just stepped out of a salon. Finally Sharpton was ready to speak.

“No justice!” Sharpton bellowed in his throaty baritone.

“No peace,” they responded with a roar.

“What do we want?” he implored them.

“Sharpton.”

“When do we want him?”

“Now.”

Sharpton, who is five feet ten and has trimmed down to 270 pounds, was just getting warmed up. He was running on adrenaline now, and he was ready to demagogue the senior senator from New York. “Moynihan says the problem in the black community is single-parent families. Well, I was raised by my mother. What kind of misogynist are you that you blame helpless women? You beat up on them rather than do your job,” he screamed as if Moynihan were there in front of him.

“I’ve been fightin’ since I came out of the maternity ward, and I tell you Moynihan is not gonna be re-elected,” Sharpton said, looking to the people in the balcony. “I watched my mother get on the subway every day to go scrub people’s floors.”

“Say it, Rev, say it,” rose the cries from the audience.

“We know it’s true, brother.”

“In my mama’s name,” came the crescendo, “I will run for the United States Senate.” With that, the crowd literally jumped out of the pews. “Sharp-Ton. Sharp-Ton. Sharp-Ton.”

There was no denying the fact that it was great theater, but it was more than that as well. With all of the invective and the oratory about accountability and unity, the rally was really about who will rise out of the pack to lead New York’s black community in the post-Dinkins era. Because there is no obvious successor, the battle has been drawn between the baby-boomer radicals—the defiant ones—and the older politicians who built careers on the more accommodating traditions of the civil-rights movement. It was, when you stripped away the theatrics, the trash talk, and the brassy attempts to play to the cheap seats, about an authentic crisis of leadership among black New Yorkers.

The crisis is that the people the [black] community has shown support for of late,” Sharpton says, “are not the ones that the political and business leaders of the city are most comfortable with. That’s the crisis.”

But it cuts much deeper and wider than that. With David Dinkins, Percy Sutton, Basil Paterson, Denny Farrell, and Charles Rangel all over 60 and either already retired or clearly in the twilight of their political careers, who will fill that void? Will it be filled by Eric Adams, the contentious 33-year-old transit cop who will probably challenge Major Owens for his congressional seat? Adams has already received the backing of the Nation of Islam, which has, till now, stayed out of New York politics. Better known for his strident, unaccommodating comments than for his leadership, Adams seems always on the brink of inciting controversy. During last fall’s election, he criticized Herman Badillo for having a white, Jewish wife instead of a Latino one. “I’m not a mainstream leader. The children in my community are dying and need help,” says Adams now, “and there’s nothing that will stand in my way. So if I have to say things that make people uncomfortable to get their attention and to say that I’m angry, then I’ll say them.”

Will the void be filled by Adam Clayton Powell IV, the two-term city councilman who is considering a run against Charlie Rangel, the man who unseated his father, Adam Clayton Powell Jr., in a bitter battle more than twenty years ago? Rangel is now one of the most powerful members of Congress. Powell’s good looks and soft voice mask a radical spirit. “Black people shouldn’t criticize Farrakhan at all,” he says flatly, even alarmingly. Powell, 31, rails against conditions in the black community but offers no specific plan to improve them. Young blood and a vague insistence on change are his solution to Harlem’s suffering.

Will the void be filled by Basil Paterson’s son David, 39, a thoughtful state senator who represents Harlem and the Upper West Side? Though he is widely regarded as a rising political star. Paterson is sometimes criticized for trying to be all things to all people. However, he is one of the few young leaders who are generally respected by both firebrands and moderates, blacks and whites.

And then there is the new, more statesmanlike Al Sharpton, who has even been encouraged in his run for the Senate nomination by David Dinkins. Though Sharpton, 39, is no longer the loose-cannon Don King of local social activism, questions remain about how sincere he is in his apparent new seriousness and prudence. At the Bethany rally, he told the crowd that lawyer Alton Maddox—who was suspended for ethics violations in the Tawana Brawley case—would be his campaign chairman and that there is no fight he would take on without him.

“Over the the next twelve months.” says Dennis Walcott, the head of the New York Urban League, “what will emerge along with the results from the primaries is the course of New York’s black community for the next several years.”

It is because the stakes are so high that the rhetoric has gotten so ugly. “Toms.” “Negroes.” “Punks.” “Cowards.” These are insults that resonate loudly for most blacks, striking at the foundation of a leader’s credibility. The outsiders hurling the epithets are in essence saying. “Here’s a man who is not black enough.” Often it seems that any leader who breaks rank is vulnerable—even if he’s only separating himself from the most dishonest or ghastly statements. At Bethany, Sharpton warned the crowd not to be fooled by “people who look like us and talk like us but don’t act like us.”

Sharpton says black leaders can have divergent opinions as long as they are expressing what they truly believe—not what a sponsor tells them to say. “Giuliani may call a black leader and get him to attack me, and he’s doing it only because Giuliani made him, to get a contract or to get an appointment rather than because that’s what he really believes. That’s the difference between those who project different views and are acceptable and those who aren’t.” This tension among New York’s black politicians has been put on vivid public display by the Louis Farrakhan debate. Though Sharpton has said he doesn’t agree with many of the statements made by the Nation, he, like so many others, has refused to definitively push them away because of the street-credibility problem.

But surprisingly, when he preaches in black churches in the city and around the state, far away from the eyes and ears of white people, he sends a different, more reasonable message. Instead of celebrating victimization and calling for black unity at any price, he’s painfully candid. Sharpton can do this because he has built up enough credibility in his account, so to speak, to now risk making a few withdrawals. “We strove for what was right even if wrong was done to us. That’s real black history,” he told a congregation in Queens recently. “Martin didn’t die so you could be no dope pusher. Malcolm didn’t take seventeen bullets so you could call your mama out her name. When we had no rights, we respected and loved one another. We’ve gained the world and lost our own soul. We will be the disgrace of black history if things don’t change.”

Despite the city’s demographic reality—non-Hispanic whites now make up only about 43 percent of the population—blacks do not hold a single citywide office. And while there are 14 African-American City Council members out of a total of 51, Mayor Giuliani has only just named his first black to a senior post. Absent any strong, coherent voice from the black community, Giuliani has virtually no incentive to work with anyone claiming to represent it. He can pursue his own agenda with impunity, as he did in the recent controversial incident at the Harlem mosque and as he is doing in the current budget struggles. “We really have to fight for everything now,” says Harlem councilwoman C. Virginia Fields. It’s not much better in Albany. Controller H. Carl McCall is the first and only black person to ever hold a statewide office—and he’s in that job simply because he was chosen by the Legislature last year when Republican Edward Regan retired. He still must prove he can win the position in this fall’s elections.

Many black politicians believe that although the void is not new, what is different now is that it’s being recognized and talked about. “The lack of leadership behind David Dinkins, that gap,” says David Paterson, “has always been there. I don’t think enough people paid attention to it.” It is true, as Paterson points out, that the next mayor’s race is not until 1997, but much of the current jostling for position is with an eye toward that campaign. And unless things change dramatically before then, there isn’t one plausible black contender on the horizon.

The fact that there is no one now prepared to step out from the shadow cast by Dinkins would be easier to explain if he had been a more dominating, powerful, and charismatic figure—a giant political oak that created so much shade that nothing grew around him. But Dinkins was a fairly spindly, sickly political specimen. What happened is that with a black man in Gracie Mansion, much of the black political machinery switched to its energy-saver mode. Some observers believe that Dinkins’s term as mayor simply masked the leadership problem. J. Phillip Thompson, a political-science professor at Barnard and a former Dinkins-administration official, points out that during Dinkins’s term, there was never a specific agenda presented by a unified black leadership. “The challenge for black leaders,” Thompson says, “is how to unite and around what program.”

For the insurgents, the answer to this question rarely extends beyond the rhymes, the alliterations, and the heat of their rhetoric. Real answers to the intractable problems are harder to come by. Eric Adams, however, has presented a detailed crime plan— structured around taking back the city’s neighborhoods ten blocks at a time—to Giuliani and to Police Commissioner Bratton. But with or without specific programs, the activists believe the time for change has come.

“Our starting team is scoring no points,” says Adams, in his assessment of the incumbent leadership, “so how much worse can I do? If you walked down your block and your children were playing outside and someone’s selling drugs, shootin’, you as a man are not going to allow that to exist. No matter how poor we are, no matter what our state is, as men, we should not be allowing what exists in our community.”

Four-term Queens congressman Floyd Flake—an incumbent who escapes the wrath of the new generation because of his community work—believes more neighborhood and church leaders need to get into politics. Flake himself, a minister who preaches to several thousand people every Sunday, was pushed to run for Congress by the residents of southeast Queens. “We need a new kind of activism,” he says, “the kind of activism that creates resources and remedies, not agitation and confrontation.”

In its starkest terms, the crisis stretches beyond who currently sits in City Hall and who will run for what political office. Like the battles taking place nationally—over integration, separatism, Afrocentrism, Farrakhan—it is also about philosophy and outlook. It is a fight over who will set the black political agenda and who will set the standards by which the leaders are judged. This kind of ideological infighting has gone on at the top tier of black leadership for decades.

“We can hark back to the somewhat mythical days of Martin Luther King,” says Dinkins’s deputy mayor Bill Lynch, who now works for billionaire Ronald Perelman. “I say mythical in the sense that before [his assassination in] Memphis, his popularity had, in fact, waned greatly. And before the march on Washington, there was Whitney Young, Roy Wilkins, A. Philip Randolph—you name ‘em,” says Lynch of the leaders fighting to control the black agenda. “And you even had the split within the civil-rights movement of the young Turks versus the old Turks. I think you see a lot of that same thing going on right now.”

What’s different, however, is that it is much harder to clearly frame the issues, which are no longer legalistic. And as long as the leadership vacuum exists at the top, those with the loudest voices—the provocateurs, the demagogues, the hatemongers—are the ones who will attract the most attention. The problem is compounded by local television’s dangerous appetite for the most outrageous possible sound bite.

“It’s like what I said about rappers,” says the Reverend Calvin Butts, 44, of the Abyssinian Baptist Church on 138th Street, whose own potential to be the black leader was set back when he endorsed Ross Perot for president. “They’ve got to see who can come up with the filthiest line next to remain popular. Well, if I’ve got to outdemagogue the first demagogue in order to get the attention of my community, then I don’t deserve that attention. We all have to be careful,” he warns, “and I’m not speaking in racial terms—well, maybe I am to an extent—because given the kind of malaise, the despair that has spread across the country, it’s fertile ground for those who can stir our emotions and get us to respond based on our fears and our anger.”

Though the Democratic primary is still almost six months away, Al Sharpton has already logged more miles, kissed more women, scarfed down more horrendous banquet food, sat in more church basements, spoken to more trade associations, preached more sermons, given more interviews, and had his hair done more times than any other candidate will manage to do during this or perhaps any campaign season. In truth, it’s as if no one ever told him that the 1992 race was over. He has, to great effect, just kept running.

For the tireless street preacher, this marathon has produced startling results. Once, it was easy to dismiss him as a con man, an FBI informer, a publicity monger, a hustler, a clown, and a bilious racial blowhard. He is all of these. Sharpton seemed, as he strutted from one repugnant racial sideshow to the next, an opportunist without a moral center.

But he actually has, apart from his recent photo-op church baptism, been reborn. Just imagine someone telling you back in the late-eighties Tawana Brawley days that Sharpton would mount a serious, dignified, issue-oriented campaign for the United States Senate in 1992. And that he would conduct himself so admirably, by comparison with the mainstream contenders, that the governor of New York would actually call him the “classiest” candidate of the bunch. That he would get 167,000 votes statewide, 21 percent of the vote in the city; finish ahead of Liz Holtzman: and do it all while spending a measly $60,000.

His repackaging and repositioning have been swift and seamless. It is now simply taken for granted that he’s the national director of the Rainbow Coalition’s ministers’ division. No one is astonished when he joins Nelson Mandela’s entourage in New York or Jesse Jackson for a meeting with the editors of Time magazine. No summit gathering of powerful black leaders these days would dare leave Sharpton off the list. He is, despite everything, in the mainstream.

This year’s primary run will be different for him from the 1992 race. In the first place, there are now expectations that must be met. A poor showing could seriously damage his reputation as a political force. However, given his opponent, that doesn’t seem likely. Instead of running against three white liberals, at least one of whom—Elizabeth Holtzman—had a significant track record in the black community, Sharpton is taking on Daniel Patrick “Benign Neglect” Moynihan. The powerful senator may be the chairman of the finance committee and a charming, innovative, towering thinker, but he is, for many blacks, the apotheosis of the white devil. For Sharpton, this means that instead of getting a little less than 70 percent of the black vote, as in 1992, he could get better than 90 percent of a much stronger turnout, as well as some votes of whites inclined toward symbolic “progressive” gestures.

The emergence of Sharpton as a political power broker in New York over the past three years has amazed black insiders like Lynch. “In 1982, before Jesse Jackson and before David Dinkins,” says Lynch, “Carl McCall got 400,000 votes in a losing bid for lieutenant governor, and he wasn’t made king. As I sit and watch this now, I say to myself, ‘I can’t believe it.’ ” He’s not alone. But even those black politicians who resent Sharpton—and the resentment is intense—are envious of his extraordinary ability to use television and to manipulate the conventions and symbols of the black struggle. Every aggravating Day of Outrage march, every mindless cry of “No justice, no peace!” and every appearance with a black family grieving over the murder of one of its members has left an image of Sharpton burned into the public psyche. He is, for many white people, something that drives them nuts, like a pebble stuck in a shoe. And he is for many blacks—because he drives white people nuts—a heroic crusader.

The most important part of the shift for Sharpton—along with his buffed and modulated image—has been his ability to reach the middle class. “The black middle class has found that there hasn’t been the kind of inclusion that they had expected,” says Lynch, who lives in Harlem and will work on Cuomo’s campaign as an unpaid adviser. “There’s a feeling that progress, if not having come to a halt, has at least slowed way down. There’s a feeling that we need to go back to the streets. Middle-class blacks [say,] ‘I put on a tie every day, I go to work, I pay my taxes, I send my kids to school. I’m an upright citizen, but I’m not respected in the same way.’ “

Part of the frustration that Sharpton has tapped is with the political process itself. “There are a lot of [black] people saying Dave Dinkins did everything you wanted and you [whites] still didn’t vote for him,” Sharpton says, “so maybe we do need an Al Sharpton who will confront you.” Over and over, black politicians talk about the impact that the Dinkins defeat has had on the way blacks in the city view the system. People are angry not simply that he lost but because of the way he lost. There is a strong sense that in a city where Democrats outnumber Republicans by five to one, the party didn’t work hard enough for him. And that despite his efforts to reach out—efforts that David Paterson, for one, says could be seen as obsequious—whites abandoned him in droves. Though there has been talk of forming a third party, it has not progressed beyond the exploratory stage.

For now, Sharpton, of all people, is working within, albeit barely within, the system. His epiphany came on January 12, 1991, at the end of a five-inch kitchen knife thrust into his chest by a crazed white man in Bensonhurst. When he woke up in Coney Island Hospital after the stabbing, he says, his life, his activism, and how he conducted himself took on a different hue. “I come out of the King-Powell-Jackson house, and I’ve begun to take that tradition and my relationship to it more seriously,” he told me one recent afternoon. “I know now that I have to weigh what I’m doing based on what I’m trying to achieve, and not just go for the cheap rhetoric and the rap.”

Already the Sharpton ascendancy is having an effect on the backstage strategizing of the Democratic Party. Though the official party endorsement will obviously go to Moynihan, everyone is tiptoeing around Sharpton for fear of alienating him and, by extension, his constituency. “At some point, these [black Moynihan supporters] are gonna have to ask themselves,” Sharpton says, “if they come out strongly for Moynihan, how do they call me after the primary? And how do they go to the black community in the name of unity when they didn’t practice it themselves?”

But where’s the beef? Is there a Sharpton agenda, a set of achievable goals? Is his new image a charade? Ask him once what he wants out of all this and he will tell you that everyone should stop trying to be his psychiatrist. He says he absolutely, positively wants to be a United States senator. Ask him a second time, when he seems in a more introspective mood, and he will say, “I may not ever be the first black senator from New York or the first black governor of New York. I may not ever even be mayor. But I do think I could be the Jesse Jackson of New York politics. And it takes somebody to create the climate so that David Paterson can become the next David Dinkins.”

In New York, the gulf between blacks and whites seems to widen with every slight, every assault, every misplaced nuance in the public discourse. Form has taken precedence over content to such a degree that it is just about impossible to have an honest public discussion about any issue involving race—which means just about every critical issue facing the city. Just as in the days of segregation when there had to be two of everything, one bathroom for blacks and one for whites, we have reached a point where every conflict, every debate, every confrontation, has two separate versions, one truth for blacks and another for whites. The particular incident or issue matters far less than the hyperbolic racial spin put on it. Sometimes it seems as though blacks and whites live not in different cities but on different planets.

Can you imagine the outcry there would have been, many black leaders asked me, if within weeks of taking office David Dinkins had had his own radio show on WLIB? Yet Rudy Giuliani, they argue, can have a show on WABC radio, and no one says anything—despite the fact that so much of what the station broadcasts is anathema to blacks. Blacks see an unrelenting double standard. They are told to denounce Farrakhan, but they want to know who denounced Senator Ernest Hollings in December when he implied that African leaders are cannibals. Where was the righteous indignation last October, they ask, when state controller Carl McCall—a graduate of Dartmouth and the University of Edinburgh, a former state senator and U.N. representative—was called “the nigger from Harlem” by an upstate councilman named Joseph Kover?

To successfully function in mainstream politics while at the same time maintaining credibility in their own communities, black leaders in the city and, indeed, across the country are often forced to walk a very thin rhetorical line. Statements that fly in Harlem can cause trouble on the Upper West Side. Though black politicians are loath to discuss this high-wire act, it is a fact of life for them. “I’ve been criticized by some members of my own community for trying to appease others,” State Senator David Paterson says with a heavy sigh. While Paterson argues that a politician can’t successfully say different things to different people, he knows the problem. “I’m constantly trying to explain to my white constituents why there is a certain reaction to something in the black community, but when talking among other blacks there’s no need. Everybody just understands.”

Because black leaders who openly criticize an activist or a radical run the risk of having their authenticity challenged, they habitually equivocate when they rebuke. In the case of the Nation, even mainstream leaders—people like Dennis Walcott and Calvin Butts—follow any repudiation of hate with a but, as in but I respect the work they’re doing with young black males or but look at how they build self-esteem.

So when six-term Brooklyn congressman Major Owens recently denounced Farrakhan emphatically and at length, he opened himself up to attack. “Minister Farrakhan can only fill a void that Major has left open,” says Eric Adams, Owens’s likely opponent this fall. “Those who feel people shouldn’t gravitate toward Farrakhan should realize there wouldn’t be a need it Owens and so many of our other leaders in Washington and Albany were actually bringing home the victories to the communities they represent. They’re not. There are some congressmen and state senators that actually walk out their door and people are standing in front of their offices selling narcotics.

So blacks are criticizing blacks for criticizing blacks. Paterson, among others, wants it all replaced by united-frontism and civility generally. To this end, he says, black leaders will begin to hold one another to a higher standard of discipline. “Almost in the way it must have been back on the plantations when somebody mouthed off and then everybody got a beating for it—the standard is going to be if you’re really trying to help the community and you know these statements set people off, shut up already,” Paterson says. “Criticize all you want, but don’t do it in a shrill, childish way. And don’t ascribe conduct to a whole race of people, because that’s exactly what’s been done to us.”

On the second floor over El Barrio Laundromat on Luis Muñoz Marin Boulevard (116th Street), in the heart of Spanish Harlem, is the district office of City Councilman Adam Clayton Powell. The door at street level reads, A.C.P. POWER FOR THE PEOPLE. Up one flight of narrow, dingy stairs, the glass door has red iron grating on it and has to be buzzed open.

The office wall is filled with memorabilia of Powell’s famous father. There’s a record cover from a 1967 live recording called Adam Clayton Powell’s Message to the World—Keep the Faith Baby, and there’s a drawing titled Equal Justice for All that combines portraits of the elder Powell, Martin Luther King, Malcolm X, and Nelson Mandela. In New York politics, being Adam Clayton Powell in 1994 is a double-edged sword.

“Sometimes I wish my name were David Powell. I would still get the benefit of the Powell name but also credit for what I do,” says Adam IV. “People have difficulty looking at me for myself.” He is trying to change that, and part of the plan is to win back the congressional seat that Charles Rangel wrested from his father in 1970. Though he hasn’t officially decided to run, he’s been busy looking and talking like a candidate.

“I believe over the last 24 years Rangel’s been in Congress, he’s done very little for his community,” Powell says. “Yes, he’s very powerful in Washington, but what good does it do if you can’t bring that power back into your own district? This man goes around walking and talking like he shouldn’t be challenged. Like, ‘How dare this guy Powell try to challenge me?’ What arrogance.” Rangel’s blithe response to Powell’s attack is “With his name and his looks, I’m surprised it took him this long.”

Bill Lynch says all of the party’s organizational forces will come together behind Rangel. “There are some of us who understand what real power is,” he says, “and it cannot be tampered with. We cannot just let that power be fritted away.”

While it may not be Powell’s time yet, H. Carl McCall is overdue. McCall, at 56, straddles the old generation of black leaders and the new. His race for controller this fall is the most important one for black Democrats.

McCall views his contest as a referendum on what sort of racial politics will prevail. “I’m not dealing with social issues,” he says. “I’m at the heart of the economic and financial issues affecting the state of New York. I think the people of New York have an opportunity to make an important statement. I’ve done everything you’ve asked me to do. I’ve gone to all the right schools; I’ve played by the rules. I’ve had significant positions in both the public and private sector. My candidacy is important because it’s really a test of whether experience and qualifications count, or whether it will become a matter of race.”

At a little past 8:30 on a cold Sunday night, Al Sharpton is sitting in the front seat of his black Ford Crown Victoria on the New York State Thruway. He has just finished delivering a sermon as guest preacher at the A.M.E. Zion Church in Newburgh, where he was received like a prophet. But now, Sharpton is stuck in traffic, surrounded by skiers returning to the city, and he is already half an hour late for his next appearance. Calmly he begins to work the car phone. First, he calls the Morning Star Missionary Baptist Church to let them know he’ll be late. Then he calls his wife in New Jersey (he has an apartment in Englewood and one in Crown Heights). Then he dials the Park Lane Hotel and asks for Jesse Jackson. No answer. Then he checks on David Paterson, whose wife is three days overdue, to see whether she’s gone into labor. Yes, he’s told, the baby is a boy named Alexander. Excited for his friend, Sharpton calls several people to let them know.

This is Sharpton’s personal time. Instead of being at home with his family on a Sunday night, he talks to them from a dark car because he is obsessed with getting his message out. “What a lot of people don’t understand,” he says, addressing all the criticism he gets, “is that I don’t have to do this. I could just preach and have a big church and live a very comfortable life. There are plenty of guys who live a real nice life who don’t preach nearly as well as I do. See, people don’t support me just because I criticize the status quo. They support me because they know I have fought and sacrificed to fight. Say that I make mistakes, say that I make misjudgments, but I took a knife in the chest, so at least give me credit for being committed.” How perfectly modern: Al Sharpton, the first virtual martyr.

When he finally arrives at the church on Merrick Boulevard in Queens, it is 9:15; he’s more than an hour and a half late. There are some 750 people inside waiting for him, and Sharpton proceeds directly but calmly to the pulpit, sits down, and begins tapping his foot in time to the gospel music.

He is a gifted preacher, and when he finally takes the microphone, the gift is on full display. His sermon is part Bible-thumping evangelism, part history lesson, part morality tale, and part pure entertainment. He is honest with the crowd in the kind of way that black leaders so rarely are right now. There is no effort to blame the system, no spinning of conspiracies, no double standard. This is not the itinerant troublemaker, the glowering gasbag of old. Instead, Sharpton sounds like a responsible black politician:

“What’s the point of talkin’ about how good we were if we’re nothin’ now? Go to the library and look at magazines from the sixties and seventies and eighties. Who did we have on the cover? Martin Luther King. Medgar Evers. Malcolm X. Carl Stokes. Jesse Jackson. Who we got representing us on the covers today? Snoop Doggy Dogg. Is that how you want to be remembered? It’s not enough to be angry, it’s what you do with it. Martin was angry, but he organized boycotts. He could’ve pulled his pants down and turned his hat backwards, but Miss Rosa Parks would still be riding in the back of the bus. Pregnant women were fire-hosed in the streets of Birmingham. People spent cold, lonely nights in jail. Medgar Evers got his brains blown out and had three children he would never see grow up, and our generation is too busy being angry to be useful.”

Back in the car, wearing a fresh shirt and showing no signs of exhilaration from his performance, he’s ready to go at it again. All leadership, he says, fills a void: that’s the only way anyone ever emerges. The issue for the younger blacks, says Sharpton, on his best behavior, is not should they fill it but how well can they fill it. His driver and personal assistant, Carl Redding, turns the car onto Roosevelt Avenue, and through the windshield the whole Manhattan skyline is suddenly and glitteringly visible. Sharpton doesn’t seem to notice. “There’s gonna come a time when we’re gonna be the old guys,” he says softly. “In the end, everybody’s gonna have to be judged by what they accomplish.”

And as the car plunges into the Midtown Tunnel, it is clear that by Sharpton’s own measure, he and the rest of his generation still have a long way to go.