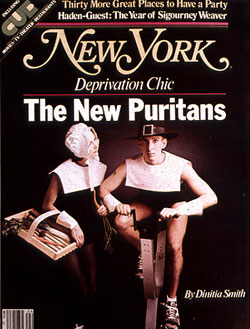

From the June 11, 1984 issue of New York Magazine.

Have I not sinned with my Teeth? How?

By sinful, graceless, excessive Eating.

—Cotton Mather, on having a toothache.

Feel the burn …

—Jane Fonda

Dawn on the Upper East Side. A small rain falls, a chilly mist hangs over the cherry blossoms in Carl Schurz Park. The only people on the block are porters emptying garbage, doormen staring listlessly out into the wet—and Mike Frankfurt, 48, of the law firm Frankfurt Garbus Klein & Selz. As he does every morning at 6:15 in sun, rain, or snow, “like the postman,” Frankfurt has risen from his warm bed, leaving his two sons, his wife, and his wheaten terrier asleep, to run ten miles. And, says Frankfurt, smiling, one of the “great joys” of the experience is the pain. “You get up every day and you never know what’s going to hurt.”

As Frankfurt and his companions—a cardiologist, a surgeon, and an executive in the fashion industry—huff and puff their way toward the footbridge at Wards Island, most of the conversation is about their ailments. “During the week,” says Frankfurt, “I get three or four phone calls about injuries.”

“We have a saying,” says Frankfurt, the sweat pouring down his face, “that to run with pain is the essence of life.”

Elsewhere on the Upper East Side, Kathy Krauch, 24, an art director at Young & Rubicam, has gotten up at 5:30 to don her black shorts with chamois padding in the rear, and set out for a twelve-mile bike ride in Central Park. Despite the early hour, the park is crowded with runners and cyclists, jostling one another as they fight for space. And on most of their faces the expression is that of, well, pain.

Before the day is over, Kathy Krauch will have breakfasted on granola, lunched on yogurt and nuts, worked a ten-hour day, swum two and a half miles, dined on vegetables, and then, despite her strained hamstrings, taken the train to Brooklyn Heights to play walleyball (a form of volleyball) until midnight. She will top this off with a couple of laps in the pool “just to cool down.” (Some days she likes to vary her routine with a soccer game.) Her swimming coach says, “I’m amazed she’s still alive.”

On the same morning, Preston Handy, 41, who is in the import-export business, has gotten out of bed and begun his eating ritual of the day. For breakfast, Handy will eat a banana, a pear, and an apple, plus some 35 vitamin pills and various herbal compounds and bee pollen—”It tastes kind of like a mouthful of dry sand,” he says. Before going to work, Handy will swim two hours; at midday he will skip lunch to work out for 45 minutes on the Nautilus machines at his local gym; in the late afternoon, he will run six miles around Central Park. He will then come home to a dinner of a yam and a baked potato, pasta “with a minimal amount of sauce,” vegetables, lecithin liquid—”It’s like licking the underarm of a snake”—and a multivitamin, “to cover anything I’ve missed.”

Handy, Krauch, and Frankfurt are emblematic figures of the New Puritanism, a movement that has converted many New Yorkers into hyperactive ascetics. It is affecting their eating habits, recreational activities—even, in some cases, their sex lives. (Some people, worried about herpes and AIDS, deliberately shun sex; other passionate exercisers find that several hours of running and swimming leaves them without enough energy—or interest.)

New Puritans are not merely concerned with developing clearer complexions or trimmer thighs. They pursue self-denial as an end in itself, out of an almost mystical belief in the purity it confers. They work hard and play harder—if your idea of play is Olympic competition. At a recent dinner party, as midnight approached, one of the guests, a financial analyst, announced that she had to get home to do a few more hours’ work before she turned in. “I need only four hours’ sleep,” she boasted. “And I never eat breakfast or lunch these days—only chocolate.” Quickly the conversation became a contest of who could sleep least, eat least, and run most. Another woman confessed to needing six hours’ sleep a night, but, she said, “I’m running ten miles a day now.” One bemused guest thought, “This is deprivation chic.”

Abstinence and self-mortification are the cultural messages at late-century. No. 1 on the New York Times best-seller list of how-to books is Eat to Win, which advocates a competitive diet of mainly potatoes, vegetables, and pasta.

Not content with the New York City Marathon (17,000 ran last year, up from 2,400 in 1976), local athletes are looking forward to the triathlon, which the New York Road Runners Club is planning for August. Participants will get the chance to swim 1¼ miles in New York Harbor, ride a bike 23 miles, and then run 6 miles around Central Park.

Swim in New York Harbor?

“I’ve done it,” says Bill Noel, who gave up his job as a vice-president of a clothing company to be the director of operations for Road Runners and who does not let a bout with the flu or feet blistered from new fins keep him from his swimming class. He also runs with an arthritic foot.

Of course not all New Puritans are “kamikaze-masochistic freaks,” as Mike Frankfurt puts it. (Frankfurt says he is careful to “make time for my family.”) But while the benefits of moderate exercise and the value of a high-fiber, low-cholesterol diet are enshrined in the canons of medicine and the annual reports of the publishing world, and while it is probably a good idea to use a little caution in choosing a sex partner, the New Puritanism goes well beyond the minimum daily requirements for sound minds in sound bodies. “It has,” says swimming coach Douglas Stern, “nothing to do with health.”

Two months ago, Stern offered a fitness seminar in Puerto Rico that he called “Pain in the Sun.” Thirty-one participants paid $600 each to run ten miles, then swim four, and bike another ten every day for a week. Stern also did a brisk trade in T-shirts with such slogans as NO GAIN WITHOUT PAIN and PAIN BRINGS FAME. Pain apparently brings profit, too, as at least one manufacturer has recognized. On New York City buses, an ad for Nike running gear pictures sweat-drenched athletes at the end of a race, slumped in exhaustion or gasping for breath against a mystic twilight. How awful it feels! How glamorous it looks!

Like the old puritanism, the new puritanism is a religion, a word that recurs in conversations with its devotees. Marathon running is not just a fashion, says Mike Frankfurt, “it’s a religion! There’s a purity about it, an honesty in the sharing of it. And what a spectacular way to begin the day, with the sun rising over the Triborough Bridge!” Long-distance runners speak of achieving a transcendent state after hours on the track. (More prosaic medical men call it hypoxia, or lack of oxygen in the brain.) Kathy Krauch, sitting in her sparsely furnished apartment, seven pairs of athletic shoes for her different sports in a line on the floor, talks of being engaged in “a quest for perfection.” Douglas Stern says that his swimming pupils look on him as a sort of guru. “They get their notebooks out and take down everything I say. I try to tell them it’s just a game, but people want answers to their lives.” Allen Guttmann, professor of American studies at Amherst and author of The Games Must Go On: Avery Brundage and the Olympic Movement, sees “residues of ancient self-flagellation rites here. Some of those people’s lives are like parodies of the early tales of Christian martyrs.”

BEYOND PHYSICAL FITNESS: New Puritans don’t just want clearcomplexions or trim thighs. They pursue self-denial as an end initself, out of an almost mystical belief in the purity it confers.

While the old Puritans, however, worked hard and forswore pleasure for the good of their fellowmen and the glory of God, the New Puritans, with their “creeds that refuse and restrain,” worship at the temple of the body. Dr. Michael Sacks, associate professor of psychiatry at the Cornell University Medical College and editor of Psychology of Running, calls the New Puritanism “the old Puritanism turned inward. People aren’t abstaining, making themselves strong, to serve the community. They’re perfecting their bodies so they can reward themselves, gain power, or simply feel better and be admired.”

In their desire to see earthly results for their strenuous purity, New Puritans are part of the American tradition that equates exercise and good eating habits with material progress and spiritual well-being. In the nineteenth century, the Muscular Christianity movement advocated regular exercise to improve one’s moral state and reduce lascivious thinking. Sylvester Graham, inventor of the eponymous cracker, preached “moral vegetarianism” and collected a band of followers, the Grahamites, who liked nothing more than a hearty meal of honey, apples, and cold water. (John Kellogg, who was influenced by the Grahamites, created a cereal designed to cut down lewd thoughts—Kellogg’s cornflakes.) Nowadays, says Guttmann, “the New Puritan is the secular equivalent of the muscular Christian. People believe that if you run the marathon you will somehow, mystically, become president of your corporation. You martyr yourself in order to achieve.”

Other New Puritans, though, may be in revolt against the self-indulgence and materialism of their society. “People are feeling that society is overly comfortable,” says Christopher Lasch, author of The Culture of Narcissism. “We’re eating too much, buying too much of everything. People aren’t being challenged by anything. It’s not enough now simply to move up the corporate ladder.”

One former radical of the sixties points out that deliberately going without meat and drink is one way of advertising that you have no problem getting them. (Studies have shown that runners do tend to come from affluent backgrounds.) “This movement is just another form of commodity fetishism. It’s a way for people who’ve had money and comfort all their lives to turn against food and comfort, and to mock working-class people. If you’ve just made it, if you’re a person who has finally got a decent income, then you can appreciate what it is to eat good red meat. And if you have two jobs, then you don’t have the time or energy to run ten miles a day.”

Historian William Leach, a fellow at the New York Institute for the Humanities, thinks the New Puritanism reflects a pervasive and widespread sense of guilt. “The sixties generation is no longer engaged in political activity—it has joined the society now. People feel profoundly guilty and are directing that guilt against themselves. Running, fasting, enables them to feel whole and pure and clean again.” Leach, author of True Love and Perfect Union, a historical study of feminism, also notes the increased participation of women in sports that require self-mortifying feats of endurance and pain. That, too, may be a guilt reaction. “They have rebelled against the life-style of their mothers—their participation in sports to the point of pain may be, in part, a ritualistic expression of guilt, at the same time giving them a sense of mastery and power.”

New Puritans may feel that they’re expiating not only their own guilt but that of society as a whole. Most cultures have rituals in which certain members of the tribe symbolically purge themselves of the sins of all. In the sun dance of the Oglala Sioux, selected warriors would pierce their chests with skewers attached by thongs to a pole. Slowly the warriors would dance backward, ripping the flesh from their chests as they freed themselves from the spikes. Their suffering was meant to ensure the continued benevolence of the sun and the Buffalo Spirit.

In today’s increasingly secular and fragmented society, it is not surprising that some are exalted by any public display of endurance and triumph. In an essay, “Masochism and Long-Distance Running,” Arnold Cooper, a psychoanalyst and professor of psychiatry at Cornell University Medical College, wrote, “Perhaps a culture such as ours, lacking appropriate ritual and order, seizes upon any opportunities to provide social unity through shared ritual suffering. It may be no accident that distance running has become popular at the same time that our society has allegedly become more self-centered and narcissistic.” And if the motives for this performance are dubious, who can say that the results are uninspiring? Doesn’t even the most hardened guzzler of heavy cream, the biggest fan of the electric pencil sharpener, feel a surge of awe and envy when the runner breaks through the tape, when the marathon man or woman crosses the line?

THE FLESH IS STRONG: Like their predecessors, many of the NewPuritans are striving to repress every sort of appetite. Some are runningas fast as they can from the problem of sensuality.

Whatever their self-denial does for other people, New Puritans insist that it makes them feel much, much better. The playwright Jean-Claude van Itallie, 48, author of America Hurrah, says that “whenever I wake up in the morning feeling depressed, I know it’s probably because of something I ate the night before.” Van Itallie now eats no milk products, meats, salt, or sugar, and hardly any starch, and drinks no coffee, tea, or alcohol. Neither does he eat breakfast—he wants to “let the body clean itself out. I also try to fast one day out of every month and one week out of the year.” He follows a daily program of jogging, weight lifting, aerobics, or yoga. “Eating properly and exercising,” he says, “is a way of reaching the mind through the body.” Frankfurt, agreeing, claims that “long-distance running saves thousands of dollars in analysts’ bills.”

Many experiments have tried to show that a well-disciplined body leads to improved mental health. In the late seventies, an experiment was conducted at the University of Wisconsin to see if exercise reduces anxiety. Twenty-five people walked on a treadmill, 25 practiced meditation, and 25 sat and read Reader’s Digest. Each of the groups measured the same reduction in anxiety. Obviously a certain degree of exercise makes some people feel more optimistic, but the cause-and-effect relationship still has to be scientifically proved. Much of the evidence is anecdotal. Dr. Henry A. Solomon, a cardiologist at New York Hospital and author of the forthcoming The Exercise Myth, says, “Many studies of exercise and alterations in mood involve relatively few people observed for rather brief periods of time, methodologic problems that render conclusions hard to apply to the multitude that has taken up exercise as a way of life.” One also needs to ask whether feeling good is always good for you. “The masochist enjoys his pain,” says Dr. Sacks. “The sense of well-being in the runner may relate to the release of endorphins and hormones. The anorexic feels better, too.”

Psychoanalysts believe that it is no accident that running mania has arisen along with an apparent increase in anorexia nervosa. (Because anorexia was only recently identified as a disease, figures are hard to come by. The New York Center for the Study of Anorexia and Bulimia, however, reports an increase in requests for treatment from 30 in all of 1980 to 252 in the first five months of this year.) The late Dr. John Sours, an analyst at the Columbia Psychoanalytic Center, was among the first to note the connection. Both compulsive runners and anorexics, said Sours, believe they should endure agony without really asking themselves why. Both are hyperactive, hardly ever tired. Both have a profound fear of gaining weight, and both, he wrote, like to start their physical routine before sunrise and to maximize pain and minimize pleasure in their attempt to master their lives. Dr. Sacks agrees that “both groups are living out fantasies of ultimate control. They are saying, ‘I am powerful enough to control basic appetites.’ Nowadays, people no longer feel they can control events outside themselves—how well they do in their jobs or in their personal relationships, for example—but they can control the food they eat and how far they can run. Abstinence, tests of endurance, are ways of proving their self-sufficiency.”

Van Itallie would put it differently. To him, the New Puritanism represents a mature trend in society, “a moral reaction against consumption, an attempt to put the brakes on. Advertising plays on all our desires, tells us what to want. We have to begin to distinguish between one need and another, to figure out what we really want.”

Like the old Puritans, the muscular Christians, and the “moral vegetarians,” New Puritans, historians say, are striving to repress every sort of appetite. Their rigidity means a freedom from choice, a bar against temptation. They are running as fast as they can from the problem of sensuality.

Laura Redding*, 28, is an assistant to a top fashion designer. Laura lives alone and has no lover. Every night at one she runs five miles. By day, she exists “mainly on a diet of ‘kirbies’ and rice vinegar,” because “meat slows me down.”

Kirbies? What are kirbies?

“The little cucumbers they use to make pickles.”

Redding, like a lot of the New Puritans, also works long hours. “It all started because I didn’t have time to make myself a roast-beef sandwich every morning. It was easier to plunk fifteen kirbies in my bag. I never have time to eat a real meal. I need an instant meal, and kirbies are better for me—there are no calories, no sodium.”

Sometimes Redding goes a little wild. “I’m really hooked on guacamole and corn chips,” she confesses in a Mexican restaurant one evening. And there are days when she has sudden cravings for egg sandwiches with ham.

What about desserts?

“What I do is feel and smell,” says Redding with a laugh. As a strawberry mousse arrives, she dips a long finger into the dish and—smells it.

If New Puritans don’t eat a great deal of food, they do take a voluptuous pleasure in thinking and talking about it. Laura Redding remembers the rich dinners her English-born mother served, “huge meals with roast beef and Yorkshire pudding, and trifle for dessert.” Preston Handy came from a well-to-do family, he says, sitting in his two-bedroom apartment whose furniture is almost entirely hidden by sports paraphernalia, sports magazines, bicycles, and bicycle parts. “We always had T-bone steak at home,” says Handy. “We always ate better than other people. I have fond memories of all those foods. Unfortunately, a banana doesn’t have a bone.”

Even now, Handy is beset by thoughts of forbidden foods. “There’s a great raisin-pumpernickel bread at Orwasher’s, on 78th Street. I try and stay away from it. And Miss Grimble makes a great peach-and-strawberry pie. I love Entenmann’s lemon pie too. I used to eat a whole one at a time,” he says, his voice trailing sadly off at the memory of these luxuries past.

It is nearly midnight at the St. George Health and Racquet club. Kathy Krauch is still playing walleyball. Her face is red, the sweat clings to her hair and runs down her face and back. Her body has a year-round tan, and she has the well-developed trapezius muscles of a male athlete. “Five minutes before closing,” the loudspeaker warns, but still the players play. Tomorrow will be a particularly hard day because Kathy has a soccer tournament.

Finally the lights dim, and Kathy must cease. Relaxing for a moment, she examines a bleeding cut from her soccer game of the day before, and stretches hamstrings, which she injured in the Mighty Hamptons Triathlon last September. Kathy remembers “the cramps in my stomach, the way my limbs shook. I could barely walk.” And yet the next day she played a soccer game. She knows that to heal her strained hamstrings “I should probably stay off my legs a couple of months.” But even now she is making plans to compete in the July 4 New York-Philadelphia triathlon—to swim 2 miles in the ocean, bike for 90 miles, and then run another 6 miles—to go even farther, to achieve new heights, in her never-ending quest for perfection. And maybe, with her new copy of Eat to Win, she just will.

In Manhattan, on the Upper West Side, Laura Redding is telephoning a girlfriend across town. “I’m coming!” she cries. Wearing her Gore-Tex windbreaker and New Balance running shoes, Laura steps out of her high rise and takes a cab east. Rain spatters the windshield, but Laura is undaunted. At Park Avenue, she gets out and begins the run toward her friend, heading south to meet her. The rain plasters Laura’s hair down, but she keeps on going, past the doorways with their golden and inviting light, past a group of late-night revelers, young men in black tie, a girl in an ermine jacket, and now Laura can feel the stitch in her side, the pain in her throat and her chest, but still she runs, onward and upward.

* Not her real name.