A woman I have known for many years did something to her face not all that long ago, and for a few weeks afterward, I was not able to put my finger on it. Did she get her eyes done? Restylane injections? Botox? Then I thought, Oh dear God, she got a face-lift. No one whom I consider a friend and a contemporary had yet gone that far. But there was no denying she had done something major, and frankly I was worried. Had she ruined her pretty face? As the curtain of hair slowly parted a little each week, I could see that her lips were bigger. Nowhere near overcooked-hot-dog-turning-inside-out bigger like Meg Ryan’s, and not even duck-bill bigger like Courteney Cox’s—but big enough to make me feel uncomfortable looking at her mouth when she talked. Don’t look at her lips!

Then one day, about a month later, I ran into her at a party and she looked stunning. The puffiness had settled, the fire under the skin had gone out. Even her lips looked like they belonged on her face. They were shaped just like her old lips, but … juicier. Her whole face looked as if it had been pushed out and plumped up—not unlike a slightly tired but still very stylish down-filled sofa that looks almost new if you keep those cushions fluffed. I cannot say that she looked exactly like her old self—but so close! A fantastic approximation! An uncanny resemblance! She looks like a very impressive artist’s rendering of her.

But there was also a faint likeness to someone else. She looked a little like … Madonna? Strange, I know, since Madonna and my friend have little in common, at least physically. But when I saw the Big Ciccone on the cover of Vanity Fair a couple of months later, I couldn’t help but notice the similarities: the Mount Rushmore cheekbones, the angular jawline, the smoothed forehead, the plumped skin, the heartlike shape of the face. Their faces didn’t seem pulled tight in that typical face-lift way; they seemed pushed out. Looking at Madonna, I kept thinking of the British expression for reconditioning a saddle: having it “restuffed.” Perhaps that’s where she got the idea to have some work done. After the hunt, Madge dismounted her trusty steed and thought, My saddle needs restuffing. And, by George, so does my face!

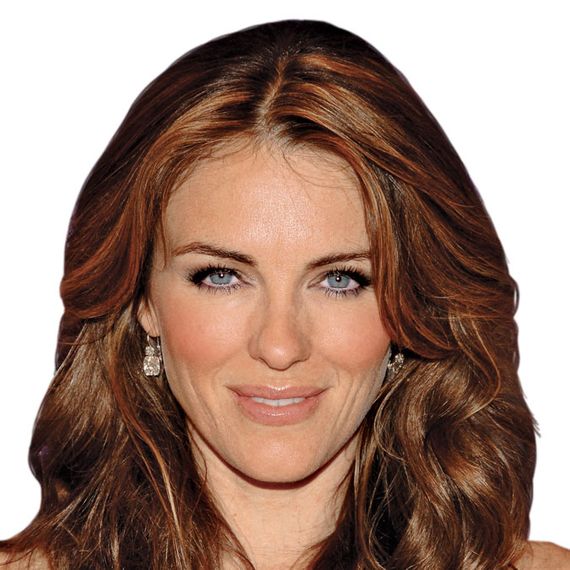

Women have been availing themselves of new faces since the dawn of plastic surgery, but suddenly it seemed that there was a better new face to be had. There is a New New Face, very different from the old one, and both my friend and Madonna now have it. Once I started thinking of it in these terms—the face as the new handbag, say—I started seeing New New Faces everywhere: Demi Moore, Michelle Pfeiffer, Liz Hurley, Naomi Campbell, Stephanie Seymour. They all have it! Even the Olsen twins seem to have a starter version of the New New Face, with their big crazy doll eyes and plush lips. Just to be clear, I don’t presume to know exactly what any of these women have done to their faces, if anything at all. It’s possible (though in some cases before-and-after pictures would seem to suggest otherwise) that this face is occurring entirely naturally—after all, these are women who are famous for being beautiful. The point is that there is a noticeable aesthetic shift happening in the face, and that it’s dovetailing with quantum leaps in plastic surgery and dermatology.

Through some unholy marriage of extreme fitness and calorie restriction (and maybe a little lipo), women have figured out how to tame their aging bodies for longer than ever. You see them everywhere in New York City: forty- and fiftysomethings who look better than a 25-year-old in a fitted little dress or a tight pair of jeans. But this level of fitness has created a new problem to which the New New Face is the solution—gauntness. Past a certain age, to paraphrase Catherine Deneuve, it’s either your fanny or your face. In other words, if your body is fierce (from yoga, Pilates, and the treadmill), your face will have no fat on it either and it will be … unfierce. It was only a matter of time before a certain segment of the female population would figure out how to have it both ways, even if it means working out two hours a day and then paying someone to volumize their faces, as they say in the dermatology business. As a friend of mine recently pointed out, there is now a whole new class of women walking around with wiry little bodies and “big ol’ baby faces.” And they look, well, if not exactly young, then attractive in a different way. A yoga body plus the New New Face may not be a fountain of youth, but it’s a fountain of indeterminate age.

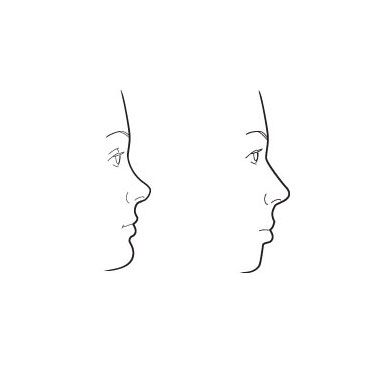

Psychologists and anthropologists have long tried to nail down what makes us perceive one face as beautiful and another not. There are theories about the math of it, the “Golden Ratio”—how, if you take careful measurements of the lines and triangles formed by a beautiful face, they will add up to the same proportions first noted by the Greeks to be aesthetically pleasing. More recently, a scientist named Michael Cunningham took it upon himself to study the faces of 50 women, half of whom were finalists in an international beauty pageant. In “Measuring the Physical in Physical Attractiveness” (italics mine), he wrote that the width of an eye, if it is to be part of a beautiful face, should be precisely three-tenths the width of the face, and the chin ought to be just one-fifth the height of the face, while the total area of the nose had better be less than 5 percent of the total area of the face or … you is ugly!

In the end, the science of beauty seems to point to a few general parameters: We tend to like large eyes, high cheekbones, a small nose, a large smile, and a small chin. What the scientific literature doesn’t mention is that we like it all to be as young as possible. This wasn’t always the case. The Gibson Girl ideal of the early twentieth century, writes Daniel Delis Hill in Advertising to the American Woman, had the features of a mature, fully formed woman: “heavy lidded eyes accented with thick lashes; fine, high eyebrows, pronounced cheekbones and firm jawlines.” In the forties and fifties, the most successful models of the day—Dovima, Lisa Fonssagrives, Suzy Parker—were elegant, haughty, aristocratic, especially when photographed by Irving Penn or Richard Avedon. The sixties and seventies brought a sea change that created a younger beauty ideal, but the aesthetic was more casual than adolescent.

But in the last ten years, perhaps with the coming of Britney Spears, the age of the ideal has dropped precipitously. Now both fashion and celebrity magazines are filled with images of teenagers—whether they’re Eastern European models or tanned California reality stars. Their faces are plump and dewy and flushed with youth. As thin as their bodies are, they still haven’t entirely shed the baby fat in their faces. This, it seems, is what women in their forties and fifties are now after: baby fat.

It’s impossible to pinpoint exactly when or how a new aesthetic is born, but it seems clear that once we became obsessed with the baby face of the teenage girl, the world of dermatology came up with more and better ways for us to achieve the plumpness of youth. We’ve moved way beyond simply injecting bovine collagen into our lips. Today there’s a dizzying nanotechnological world of hyaluronic acid and collagen fillers—Zyplast, Cosmoderm, Perlane, Juvéderm, Evolence, Sculptra—each with a different “bead” size targeted to fill every wrinkle on the face (microscopic for the lines around the eyes, heavier gauge for a cheek or nasolabial fold). With these tools, a woman can dramatically alter her face without going anywhere near a surgeon’s office. All that’s required are twice-a-year injection appointments with a cosmetic dermatologist. And then, when a friend comments on her appearance, she’ll respond, without guile, “Plastic surgery? Me? Heavens, no!”

Time is not kind to a face. In Dr. David Rosenberg’s consultation room, a high-tech mini-theater dominated by a big recliner that looks like a seat in first class, we are scrolling through women’s faces on a flat-screen TV. “Here’s another one,” he says, as he manipulates the screen from his laptop. She’s a very attractive woman, 54 years old. “What she’s developing is descent,” he says. “The jowls have made the jawline more square. A little bit of hooding on the upper lids.” Descent. Falling. Your face is falling. The sky might as well be falling. “We all have our pretty days, and some people are more beautiful than others,” says Rosenberg. “But we all age the same way. Our necks get loose, and our eyes get tired.”

Rosenberg is a fit, compact, and stylish 41-year-old with a sweet, almost feminine nature. He has three children with his wife, Jessica Lattman, who is also a plastic surgeon. And hilariously enough, he has a crooked beak—he needs a nose job!

Today alone, starting twelve hours earlier, Rosenberg met with 50 people in this room, showing them pictures of themselves as they are and as they could be. He is the beneficiary of a whisper campaign among a certain New York–Euro society-fashion crowd for his subtle face-lifts and coveted nose jobs. (He did three times as many nose jobs this year than last.) The fashion magazines have been writing about him. In fact, just a few days after I met him, I had dinner with a good friend who is the publisher of one of those magazines. When I told her I was working on a piece about plastic surgery, she leaned in and whispered, “You must talk to David Rosenberg.” Then my friend, who will turn 60 next spring, confessed that she had just plunked down a $4,000 deposit and will be going under Rosenberg’s knife for a face-lift later this year. All told, it will cost her $30,000, including recovery in a fancy hotel and a private nurse attending to her every need.

For many women, the New New Face begins in their thirties and forties with a little Botox here, a little filler there. To extend the handbag metaphor a bit further, it is the dermatological version of the mini-Birkin. A starter bag. But real, serious, grown-up New New Face business cannot—at least at my friend’s age—be achieved with fillers and Botox alone, something she’s been doing for years, with disappointing results. For women in their fifties and sixties, New New Face construction begins far below the surface of the skin.

A cursory history of the face-lift is probably necessary at this point. In about 1905, surgeons figured out that they could make an incision in front of the ear, cut away a bit of skin, and sew it back up to make the face look less old. Then, in the twenties, the “skin flap” was invented, a procedure that involves peeling the skin back like a bedsheet, allowing for much more skin to be cut away for a tighter result. In 1976, a surgeon discovered the SMAS (or superficial musculoaponeurotic system), a cellophane-thin lining just under the skin that is part of the musculature of the face. If you lifted the skin and tightened the SMAS, you got a much bigger correction in the jawline. To this day, the SMAS operation remains the workhorse face-lift. In the mid-eighties, a Swedish doctor began to go under the SMAS, the beginning of a process that led to the deep-plane face-lift of the early nineties.

But even as surgeons worked with deeper layers of the face, the aesthetic was still a superficial tautness. “When I was in early training,” says Rosenberg, “I kept hearing the phrase, ‘This doctor makes the neck really tight.’ And that was a good thing. That was the operative word. Tightest neck out there!” The surgeries were obvious and, in some cases, seen as status symbols. “It’s like wearing a big shiny Rolex,” says Rosenberg. “ ‘I have enough money that Dr. X did it.’ ” But tight is no longer the operative word. “Eighteen-year-olds, they are never tight. What they have is definition.” (Her again: that round-and-soft-and-also-somehow-perfectly-defined teenage girl!)

What has transpired in the past ten years, says Rosenberg, is “further dissection of the deeper layers” for a face-lift that is almost entirely muscular. Rosenberg and surgeons like him go under the cheek-fat pad and disconnect the platysma, which is a sheet of muscle that supports the lower face, then they resuspend it higher with stitches under the skin. “That’s how you fix the surface—from below,” he says. “I am working on the undersurface, and everything gently comes with it. So there’s a feminine quality, it’s soft and smooth. When it heals, you don’t see tension on the outer surface.”

Rosenberg is also subtly shifting the shape of the New Nose. “Unlike a face-lift, where you are restoring what someone once had, with a nose you are absolutely changing it, making it completely different,” he says. The nose on the New New Face is strong and architectural and straight. Neither flared nor pointed. More Greek than Roman. It’s also the kind of nose job that you’d never notice without before and after pictures (note Angelina Jolie’s very slightly slimmed masterpiece). What it is most certainly not is the cute little ski-jump nose that was ubiquitous in the sixties and seventies—and even popped up again recently on Ashlee Simpson’s face. The “Diamond Nose,” as it was known 30 years ago, was named after a Dr. Howard Diamond of Manhattan, who supposedly did more rhinoplasties than any surgeon before him.

When I tell Rosenberg that a prominent fashion editor told me that people in her crowd are talking about the “Rosenberg Nose,” he is visibly moved. “Awwww. That is crazy.” He looks away for second, apparently misting up. “Nose surgery is so … hard. So technically difficult to master. You have to plan for adjustments with healing. Things settle, it’s almost like making a … a … wine.” He smiles broadly. “This is the first time I’m hearing this. You don’t know how exciting this is.”

Rosenberg didn’t do Angelina’s nose, although he wouldn’t admit it even if he had. Plastic surgeons are very careful not to talk about their famous clientele, because it is the last secret that celebrities try to keep. The stars still require after-hours appointments with an empty waiting room and a special back entrance at Manhattan Eye and Ear, where he does all of his surgery. But it’s difficult to talk about the changing aesthetics of plastic surgery without, well, examples, so reluctantly he agrees to apply his highly trained eye to the faces of Meg Ryan and Demi Moore, Old New Face and New New Face. “Meg may think she looks beautiful,” he says carefully. “But what we are picking up on is a sense that maybe there is an overinflation of the lips, there’s an overabundance of fillers in her face.” He pauses. “What I see with Demi is more of an operation. Let me say it this way: I see preservation of definition, a preservation of facial architecture. Angularity. Very pretty.” He mentions Madonna admiringly as well. “You see the architecture of the jawline, you see the architecture of the cheekbones.”

“She didn’t lose her face,” I say.

“She gained it,” says Rosenberg.

I decided to e-mail Liz Rosenberg, Madonna’s publicist since fuh-evah (and no relation to the doctor), to see if she would have lunch with me and talk about celebrities and plastic surgery. “Absofuckinlutely,” she wrote back. “Though why you think anyone I represent has done anything to their faces is beyond me. Ha-ha. Getting any artist besides Joan Rivers and Kathy Griffin to go on record about the subject is not easy. Of course one of the great quotes came from my gal Cher, who said in an interview, ‘If I want to put my tits on my back it’s my business.’ Whatever Madonna has had done—and I really don’t know—she looks truly amazing.”

A week later, the two of us are sitting at a window table at the Modern at MoMA during what has turned out to be Madonna’s biggest shit-storm in years. She is everywhere, including the front page of the Post, portrayed as a MAN EATER (while looking sort of like the Unabomber) for supposedly tempting A-Rod away from Cynthia with her forbidden middle-aged lady fruits—while at the same instant dealing with the fact that her once-devoted gay brother, Christopher Ciccone, is just beginning his Bite the Hand That Feeds Me book tour. Rosenberg, ebullient in black pedal-pushers and a fuchsia sleeveless top, tells me that she was just with Madonna while she was rehearsing for her upcoming Hard Candy tour. “She was double-Dutch jump-roping with a bunch of 18-year-old girls, and she outjumped them all. I can’t believe how fit she is.” She pauses for a moment before referencing all the recent tabloid stories. “Madonna could give a fuck. The disparity between what you read in the paper and reality is just huge. She’s perfectly fine.” She catches herself. And then lets it rip. “Guy Ritchie is homophobic? It’s so stupid. No, Christopher, it’s just you he didn’t like. It’s a Ciccone family trait: You can justify any behavior.”

I had asked her to have lunch with me before Madonna’s latest travails hit the papers because I wanted to talk to the person who, with Cher and Madonna as clients, has probably had to field perhaps the most phone calls ever about plastic surgery. Rosenberg, who has never had any surgery or even a Botox injection (“I’m not putting that poison shit in my face!”), is nevertheless practical about the cosmetic needs of her clients. “Improve the product!” she shouts. “I know they’re humans with beating hearts, but, you know, these people, they are commodities, and improving on your product is the business they’re in.” Still, she’s not about to traffic in specifics. When I ask what Madonna has done to her face, she takes a sip of water and says, “I don’t know. I have never represented anyone who has spoken to me about plastic surgery. Nor have I asked them. I don’t want to know! Anyone who has had it done, I’m all for it. It’s great. People ask me about Cher all the time.”

Cher is the very essence of Old Face cosmetic surgery run amok: too-tight skin, weird lips, eradication of interesting nose, all of which adds up to a woman we almost don’t recognize as the Cher we grew to love in the seventies. There are other, more recent examples of women who have made themselves unrecognizable as the star we once knew: Melanie Griffith, Faye Dunaway, and Jennifer Grey come to mind. They were a few of the unfortunate evolutionary steps on the way to the New New Face—not to be confused with the super-freaks and 50-footers (hot from a distance; like a cadaver with a wig close-up) who fell all the way down the slippery slope. “I once saw Jocelyn Wildenstein at an airport,” says Rosenberg. “This right here”—she touches the skin under her eyes—“looked like an ice-skating rink. I have never seen anything like it, the most translucent skin. It wasn’t human, but it was fascinating in a sort of awful but fabulous way. She must have only one layer left. These women have jumped past being uptight about it and have said, ‘I don’t even care if I don’t look human. I just don’t want to see a fuckin’ line on my face.’ ”

Instinctively, Rosenberg understands two things that many plastic surgeons agree on: One, people who start with amazing bone structure are the ones who often look better with plastic surgery. “Like Sophia Loren,” she says. “What is she? One hundred? Fucking fantastic.” And two, “you will never look natural if you get shit done to your lips.” This, of course, is the main reason that, as a friend of mine pointed out recently, Madonna is starting to look a little like Faye Dunaway: She seems to have done shit to her lips.

Dr. Fredric Brandt is routinely described in the press as Madonna’s dermatologist, though neither Liz Rosenberg nor Brandt would confirm it. One Friday morning I meet him at his offices on 34th Street. Hanging on the wall just outside his door is a giant framed photograph by the fashion photographer Steven Klein. In the foreground a toned, tanned, naked man lies out by the pool while, unbeknownst to him, Dr. Brandt, holding aloft a giant needle, lurks in the background, ready to sneak up and inject the unsuspecting hot guy (and perhaps … paralyze him! Bwah-ha-ha-ha-haaa!).

Brandt, who clearly enjoys evincing a clownishly “sinister” Dr. Evil–meets–Pee-wee Herman persona, is dressed like Simon Le Bon circa “Hungry Like the Wolf”: black parachute jacket, white shirt with big silver zipper, pointy black shoes, pegged black high-waters. His face is a smooth, frozen mask that juts outward and is a very extreme example of the New New Face—not a single line, wrinkle, or variation in tone. But it is the shape of his face that I recognize. It has the same inverted triangle shape as Madonna’s face and Naomi Campbell’s face. When he tells me that the superstar hairdresser Garren is a client and that he knows fashion photographer Steven Meisel, I begin to realize that he’s hooked into a certain crowd of people who are all connected by one degree. It is not hard to imagine that some patient zero told two friends about Brandt and then they told two friends and now many of them have a variation on the same face.

“What we notice when people age,” he says, “is that our fat pads start falling, the cheeks start dripping down, and we start losing volume in the upper face and it causes sagging in the lower face. You lose what we call the ‘youthful convexities’ of the face. And the convexities are the fullness and the roundness. And they get broken up into uneven planes. Instead of being one smooth convex plane, it becomes hills and valleys.” He pauses for a moment. “God, I wish I had my slideshow.” Then he points to his 29-year-old publicist, who is sitting silently in a chair off to the side. She is very pretty. “She has the fullness, and she has these beautiful, even, uninterrupted cheeks. And if you take a look at me—because I freely admit that I do all these things to myself and have injected myself completely—I have restored the volume to this portion of my face.” He is now touching his cheeks and under his eyes. “You can see, even though I’m not her age (he is nearly 60), I have the same type of convexities throughout here and in my cheeks. A face-lift is good for tightening, but it doesn’t do anything for volume loss, and a lot of people still don’t understand this concept.”

When I ask how much of the new aesthetic is dictated by his ideas of beauty, as opposed to advances in technology, he says it’s a combination. “I always believe more,” he says, laughing. (Bwah-ha-ha-ha-haaa!) “A lot of people start off very gradually, and then they end up seeing the light.”

It is not easy to get an appointment to see the Great Pat Wexler, Wizard of Injectables, Queen of Volume, Mother of the New New Face. I had been told by a socialite friend (in her late thirties and “loving Restylane”) that Wexler’s waiting room is “like one big cocktail party” where “the Calvin Kleins and the Carolina Herreras and the Vera Wangs” all bump into each other all the time. Wexler, who opened her practice 22 years ago, gets credit as a New New Face pioneer because she intuited that volumizing was the future: injecting and filling the face with either fat from the patient’s own body, collagen, or synthetic fillers, instead of stretching the skin tight over all that sagging infrastructure.

“That’s what I call the Beetlejuice phenomenon,” she says when we meet. “You keep pulling and pulling, and your head gets smaller, and your body gets bigger as you age, and so you wind up with this little head on this big body. But we now know that you need volume to keep a face looking young. Volume means a face that goes out. And it’s all about the cheeks and the jawline.”

When I tell her that making the face bigger or “fatter” seems counterintuitive, she says, “I know, that’s why no one was doing it twenty years ago.”

“How did you figure it out?” I ask.

“Because I was doing lipo and I don’t like to throw anything away.”

Wexler herself is a vision of creamy-white linelessness. With her super-skinny jeans, stilettos, and poker-straight fire-red hair, the 56-year-old doesn’t look a day over Miley Cyrus. She comes across as a thoughtful empath, a disposition that makes you feel like she will be careful when she liposuctions fat out of your butt cheek and injects it into your face. Her gaze is so steady that she puts me into a trance—though I snap out of it just before she can talk me into “some fillers around the cheeks for some volume that will lift your whole face and a little Botox to lift your jawline.”

There are some patients of Wexler’s who think that she could not possibly look so young without having had some kind of surgery, some even speculating that it was the legendary but decidedly old-school Dr. Daniel Baker. But as my socialite friend says, “Pat is all about doing everything but … laser, inject, fill, suck out, but, God forbid, don’t cut.”

Wexler is a die-hard believer in the power of injectables. “If you are sunken-in and hollow under your eyes because you haven’t had an English muffin in three years, you are going to look bad. You need to have a certain amount of that juvenile plumpness to look young,” she says. But, recognizing that many women have gone too far with their fat lips and paralyzed brows, she preaches moderation. When I joke that Botox has created a market for a children’s book that ought to be titled Why Does Mommy Look Weird?, she laughs. “Babies learn facial expressions from their mothers, and if all these women are Botoxed, I wonder if we’re going to see a generation of very flat-affect toddlers. You really do need to have expression. I don’t believe in trying to freeze the face.” She points to herself as Exhibit A. “I have expression. I don’t have big blown-up lips. In fact, when I pucker, I have lip lines.” She purses her lips and invites me to lean in for a closer look. Indeed, I can see that she has faint lines radiating out around her mouth. “I should do more, but I don’t have time because I’m too busy fluffing and tucking everybody else. But the more I do other people, the more I embrace my own naturalness.” I stare at her for a second. Natural is not exactly the word that springs to mind. “I love my Botox!” she continues. “I’ve done Botox for eighteen years, but I don’t do Botox to excess. I do little bits of Botox because I don’t want deep hollows.” She blinks. The corners of her mouth twitch up ever so slightly. “I can smile,” she says.

Wexler also thinks the overinflated-lip craze is finally over. Angelina may have been blessed with the perfect kisser, but it’s virtually impossible to re-create it in a way that seems natural. “Not everyone is meant to have a lip,” says Wexler. “You can’t bring a picture of a lip to a doctor and say, ‘That’s the lip I want,’ and yet women do it all the time.” She credits the model Coco Rocha for helping the thinner-lipped among us to accept our biologically determined fates. “God bless Coco! Small lips are totally in vogue right now. It’s very acceptable. There are very famous models and actresses who are totally happy to keep their thin lips.”

When I ask Wexler—who has seen a lot of faces come and go—about the difference between the Old New Face and the New New Face, she answers immediately: Ivana Trump. “When she got a totally new face in the early nineties—a new jawline, a new eyebrow arch—that was a new face. She is now aging as a whole different person. The new version of the New Face is that it shouldn’t look new. It should look like you. It should look like the old you.” Wexler, who thinks in MST (Movie Star Time), says her clients want to look the way they did “four films ago”—or about eight years in RPT (Regular People Time).

It’s a pleasant notion, and fun to say: The New New Face is really Your Old Face! “Beauty is supposed to be genetically inherited,” says Wexler. “Grace Kelly or Audrey Hepburn? That was God-given. There’s no such thing as a surgically created beauty. That would be a cheat. We think of the Pamela Andersons and the Anna Nicoles, but again, they are trivialized, mocked. They’re fake beauties, not true beauties. When people think of the standard of real beauty today, they think of Angelina Jolie. And that is a very hard standard to meet.”

Somehow the idea of maintaining, preserving, and restoring feels less like cheating. The New New Face promises to reclaim something that was lost. But does it? Even the most successful and beautiful result is something entirely different from what a woman looked like when she was 30. Demi Moore, the gold standard of good plastic surgery, does not look at all like she did when she made Ghost. The New New Face is a fantastic approximation! An uncanny resemblance! It is, at its best, a close copy of youthful beauty, not youthful beauty itself.

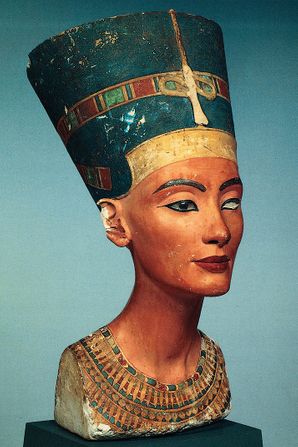

3,378 Years of the “It” Face

Photo: The Granger Collection; Musee du Louvre Paris/The Art Archive; Galleria Degli Uffizi Florence/The Art Archive; Geoffrey Clements/Corbis; Bettman/Corbis; Corbis; The Kobal Collection; Hulton Archive/Getty Images; Justine de Villeneuve/Hulton Archive/Getty Images; Adam Scull/Globe Photos; Ron Galella/WireImage; Terry O’Neill/Hulton Archive/Getty Images; John Spellman/Retna; Steve Granitz/WireImage