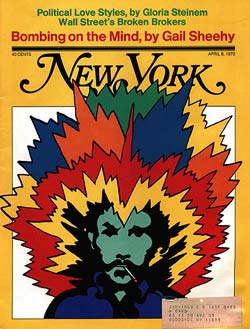

From the April 6, 1970 issue of New York Magazine.

Can that be Marc?

So thin. The young man stands on the steps of College Walk in a hooded Army surplus jacket, dwarfed by the mute stone geometry of one of our Great Universities. His pants hang. From 20 yards he looks like a stick figure in an architect’s rendering … the kind they draw with a long shadow … a single movable stick figure in a grand concrete design. It is three days after Friday the 13th of March. Three buildings have been bombed in midtown Manhattan. Marc’s friends are dropping out of sight. Ted Gold and his companions, who played with dynamite, are dead on West 11th Street. Jane Alpert, Dave Hughey and Sam Melville, for whom Marc helped to raise bail, face trial on charges of bombing two Manhattan buildings and a National Guard truck last summer. Marc knows these people. Inspector Finnegan and his subversive-chasing Red Squad know Marc.

Can that really be Marc? The silhouette is stark as an ailanthus tree, reedy and budless, waiting at the end of an oppressive urban winter for the cold spring to break. But Marc is a man, 29, Jewish, married, mild-voiced. He is dedicated to the liberation of practically everybody and normally suffers only from the standard afflictions of any white middle-class regular in the Movement: a lump of rhetoric in the throat and chronic love-hate disease.

Marc is not considered lunatic fringe. Neither was Ted Gold. Behind Marc’s Fine Arts face is a brain in good working order. It has been through many changes since childhood in St. Louis. Marc is a weathervane. The way he goes, so go the prevailing ideological winds of radicalism. His last change was to commune-ism; he is developing an urban commune where young parents, living in the shadow of the university, can leave their children free, exchange clothes in a free store and generally experiment with the extended-family idea. Several months ago Marc talked of these things and of his 4-year-old child, Meredith. Was his son in school? I asked. Actually, he said, Meredith is a girl. We both laughed, because Marc’s household is very heavy on Women’s Liberation. Nevertheless, any Jewish mother would still love to have Marc’s face in a frame on the bedside bureau. Mustache and all.

Now the young man scuffles hurriedly down the steps. Marc? The eyebrows arch up and touch, forming a pitched roof over his eyes. The mustache has dropped several notches. It hides his mouth with a dark V that matches the V of the brows, like two peace signs. Upside down.

“Hey, it’s me,” he says.

“Didn’t recognize you.”

“I know. I’ve lost a lot of weight. I lost 15 pounds in the last two months.”

“Paranoia?”

“No. Fear.”

Marc is preparing himself to die.

“When I get nervous I can’t eat,” Marc says. We are sliding trays around the cafeteria belt of Columbia’s Lion’s Den. Marc never went to school here but lives nearby. Since Abbie Hoffman gave the weather report on the campus last Friday—”New York: BOOM BOOM BOOM”—followed by the weekend’s window-smashing spree, Columbia is attracting visits from older, neighboring rads. They stop by with a sort of Parents’ Day interest.

Marc puts down a cheeseburger. Nothing else. The police have questiond him in connection with the bombings. “My friend of two years turned out to be a police plant. My line is tapped, but that goes without saying.” (Every self-respecting radical thinks his line is being tapped.)

A word hangs in the air, straining like those black helium balloons we all let loose over a sodden Sheep Meadow last October—remember? The Vietnam Moratorium? Taps? A few tears, a new hope. And then we all went home and had tea. Today the word is bombing.

“I talked to a lot of people over the weekend,” Marc says. “It surprised me.”

“What did?”

“How many people relate to bombings.”

Marc looks with condescension around the dining room, den of the Great University rads. The air hangs blue over their bridge games, tinged with the sweetness of grass.

“The most visible Left leaders are the most harmless,” Marc says. “Look around—80 per cent here are new faces.”

He clamps down on a Camel. His hidden eyes indicate that now we are going to talk about the under-underground movement, about the graduate revolutionaries of April ‘68 and the dispersed Weathermen and Mad Dogs and the Brooklyn Commune. Some are in jail. Others have made contact with better-hidden cells around the country (the figure given by one TV commentator, “based on academic sources,” is 1,000 such cells). Three tenets of the under-underground are: Keep moving. Don’t give your name. Form an affinity group. Four or five people who know and trust one another and are ready for heavy action, sharing a preference for the same tactic, make up an affinity group. In the past week the Weathermen have broken down still further; the members have spread out to work as individuals or with one other person. Then there are the roving anarchy advisers who travel the campus circuit. They appear to have staked out New York for their spring/summer offensive.

“There are literally hundreds of people living around this university who don’t show up for rallies,” Marc says. “They have spread a lot of explosives around the city. They all relate very strongly to BOOM. I do myself.”

With false cool I borrow one of Marc’s Camels. “What about the people in the buildings? They were cleared out before IBM, Mobil Oil and General Telephone were bombed, but can peple count on a courtesy call before every explosion?”

Marc rips a silver coil off his Camel pack.

“I’m not sure the kind of people who work in those buildings shouldn’t be blown away too.”

Suddenly I am not the only one trembling. Marc’s right knee begins paddling against the table leg, like a rudder out of control. What is his fear about?

He lights cigarette number three.

“I’m convinced there will be a violent revolutionary uprising this summer. Much larger than Watts. On a national scale. It will be essentially a black movement with white revolutionaries who relate to it …” Marc’s voice trails off. “In New York there’s a group …”

Pen poised, half wishing I had stayed home to pair socks, I wait for Marc to give the nod that note-taking is allowed. He spreads his hands palms up on the table. Narrow hands and finely boned, hands with many previous apologies in them.

“Why not?” Marc says. “I’m not telling you anything the Red Squad doesn’t know. In New York there’s a coalition of white radicals and two Harlem groups planning to close down the whole city this summer. Including subways, bridges and tunnels.” The Camel has burned down to Marc’s nicotine stain, but his fingers do not react. He expects the uprising will spread out of Harlem, and the next stop is Morningside Heights, where he lives.

“There are people here willing to do their part at that time,” Marc says. Long pause. He continues speaking in the second and third person. “It may be an abortive revolution but it’s inevitable and it’s going to be violent. And that means the possibility of dying. Many people I talk to now tell me they can accept their own death.” Another ghostly pause.

“Many affinity groups are dealing with death—your death,” he says.

“My death?”

“Individual death.”

“… ‘It may be an abortive revolution but it’s inevitable and it will be violent. Many affinity groups are dealing with death now.’ …”

We seem to be having a slight communication breakdown around pronouns. Marc keeps his eyes hammered into the table when he speaks. Apparently this is protocol for such conversations. Because of the vague way radicals talk about the most extreme things, it becomes terribly important to know exactly which you and they we are talking about.

“What about you, Marc? Are you ready to die?”

“Me?” His eyes sweep the room once around, as though checking out the jury. For the first time his words come out in the first person.

“I still question myself. It’s conceivable to me I could be killed on short notice for a number of activities I’m involved in.”

For comic relief, the Seeburg in the corner begins grinding out the big one from Blood, Sweat and Tears.

I’m not scared of dyin’

And I don’t really care.

If it’s peace you find in dying

Well then, let the time be near . . .

Marc is talking about how he plays out all these fairly real scenarios.

“Having to flee. How would I handle myself in a jail situation? I play out all these fairly real scenarios, like would it be better to be lined up by the state and shot or by PL and be shot?”

PL is Progressive Labor, the elitist faction that split with SDS last June, haranguing for a worker-student alliance. Its members must pass required reading in Marx and Lenin and forswear long hair, drugs and isolated acts of terrorism. PL is strong in the Boston area. At Columbia it has seven members. They wear sports jackets and dedicated-psychiatrist glasses, and their most powerful weapon at Columbia is a bullhorn. When the prevailing radical faction whips up a crowd around the Sundial, one can always count on a PL party hack to leap up and claim the rabble with his bullhorn. He makes a stunning beginning, like “Remember, when you smash windows it’s the workers who have to clean up! The real issue is the widow of an employee of this university who is living on $37.60 a month …” About here someone punches him in the mouth. As the crowd rushes off, intoxicated by its new slogan—Break the Glass of the Ruling Class—you can always hear a PL kid yelling through his bullhorn: You’re being led by a pig provocateur!

Other rads look on PLs as harmless lispers of the Maoist line. The New Anarchists know the time for strict party organization went out with the radio. Television, well manipulated, along with the telephone tree—10 people dialing friends from pay phones, who in turn dial one friend each, etc.—can gather a thousand people in the space of an hour. Ready for action. It’s beautiful. The bullhorns of the New Anarchists are the tube or the public telephone.

The chances of Marc’s being shot by PL are roughly equal to the odds on being fatally wounded by a Frisbee at Jones Beach. That isn’t what bothers me. What bothers me is those fairly real scenarios. (Herman Kahn, inside the Hudson Institute with his fatal brilliance wrapped in middle-class values, relates heavily to the word “scenario.” He gave us a Scenario for World War III. Somehow, visiting the man in his caricature suburban home, one can’t help wondering if inside Herman Kahn’s brain the theatrical genius cell doesn’t bump the bourgeois cell every so often and whisper, “Whaddya say? Let’s see how it plays?”)

What is a fairly real scenario? Real, for instance, is the house that isn’t on 11th Street anymore. The Tomb of the Unknown Radicals. As people came to visit this anti-shrine, the minute they turned onto the block their eyes would lock on the site of the explosion. No one spoke. In little strings of 12 at a time, they leaned over the wooden police horses. Silent, like the audience at a Balanchine ballet, they watched the FBI agents sift through piles of rubble with their bare hands. A shred of calico-print wallpaper. Charred pages from the Daily News. Whenever the agents with their cold stiffened hands touched a brick, they would stop and spread the dirt from around it with the delicacy of a gold-panner.

A man joins the line of onlookers.

“What’re they lookin’ for?” he asks the next man.

“Fingers.”

Who knows what went on inside the onlookers’ heads? The most obvious impression from that hole in the ground was: America’s richest children are making bombs for mother. Real ones.

Perhaps “fairly real” is watching the last frames of Zabriskie Point, closing your eyes on the floating Naugahyde fishbowl ballet of remains from the exploding houses, and dubbing in your own most hated buildings. Or seeing The Battle of Algiers for the fourth time and dubbing in your own city. Leftist college students in Manhattan don’t go to see a film called The Battle of Algiers. They go to study the scenario.

Marc wants to talk for a while about children, and what his commune is doing for them. It is not easy to talk about anything to radicals. For a journalist the first problem is to pass the ideology check:

Yes, I am a member of the bourgeois press.

No, I am not a lackey of the imperialist government.

Yes, I will contribute to your bail fund.

No, you cannot have final editing rights on this story.

After going through the whole drill you find out Marc worked on Wall Street. But that was a few years ago. He had already passed through Republicanism, shifted colleges, quit graduate school 28 points and a thesis short of his Ph.D., and was concentrating on being less of a male chauvinist in his marriage. He came to New York and worked for Wall Street magazine. He wrote in American Business on numismatics. That means coins. (Today, Marc would probably spell it Koins because the rads are now using the German ‘K’ to color their vision of a fascist Amerika.) Marc is now going to editorial meetings in St. Mark’s Church-in-the-Bowery, where he is helping to develop New York’s first radical, aboveground, daily newspaper, the Daily Planet. Meanwhile, he and his wife Patty make do working nights at freelance editing and proofreading, earning about $7,000 a year.

One doesn’t have to talk to anarchists like Marc to learn what they want. Jerry Rubin, member of the Chicago Seven presently free on bail, gives the answer. All you have to do is to read it in his new book, Do It, Scenarios of the Revolution. Scenario 40: “We Cannot Be Co-opted Because We Want Everything.”

Marc lives in the kind of building where the old standup kitchen sinks wear skirts, but the women do not. Even the mailboxes are liberated. Every one has at least two names—husband’s name and wife’s maiden name—which is the way it is done in Women’s Lib. But Columbia University owns every inch of the building and the people inside never forget it. They can’t argue with a landlord named Columbia University; they either take it or leave it.

Nine a.m., and Marc’s daughter is watching Sesame Street. Laughter drifting from her room … goon sounds of Oscar the Grump, who lives in a garbage pail and makes kids laugh about it … these happy sounds seep back through the maze of hallways over long tongues of cheap carpet curling up the wall. Marc wakes up mad. He thinks Sesame Street is the most dangerous program on the air. His daughter Meredith thinks it is worth watching five hours a day.

The words form on his lips: “Don’t watch it!” But they recede, unspoken, behind his mustache. His commune is proud to say they are not oppressors of children. When Marc and his wife plan their separate but equal weekly calendars, Meredith gets to say where she wants to go too. One morning Marc awoke without his philosophy and hollered in to the littlest anarchist:

“Don’t watch it!”

“Stop telling me!” Meredith shouted back. “I watch what I want, you watch what you want.”

“What can I say?” Marc ponders. He has tried to explain to this 4-year-old that Sesame Street is insidious, manipulating the minds of little children by using commercial techniques to “sell” them information. Everything is done to them and for them, setting them up to be turned into a little nation of consumers. Meredith goes right on digging Sesame Street.

Marc has decided there is only one way to handle it. Someday when Meredith is out at school, he will blow up her TV.

“… The obvious impression from that hole on 11th Street was: America’s richest children are making bombs for mother …”

Marc never speaks for his wife either.

Patty is a talented sculptor. As they said all through college, “very talented, for a woman,” which still infuriates her. She is sharper now with a comeback. Likely to wear a loincloth skirt to speaking engagements for Women’s Lib, but with a save-me whisper voice over the telephone. She is also pretty. In a Prince Valiant sort of way.

Patty worked while Marc pondered dropping out of grad school (“A most chauvinistic role,” he now hastens to add. “I was liberated to the extent that the woman could work. But the idea she might become famous and I would be the nobody was a hangup for me at the time. It was a very subjective thing, a very chauvinistic thing.”)

Only a year ago Patty confronted Marc with a fairly clear estimate of their six-year-old marriage, from her point of view: “This relationship is essentially rotten.” He agreed. Soon thereafter he began cleaning Meredith’s room. Determined to keep his marriage together, Marc now attends a weekly men’s consciousness-raising session.

Patty, on the other hand, is dedicated to the overthrow of the male power structure. But she is not hopeful. Today, interrupting work on a feminist article, she sits calmly back on her corduroy sofa … exceedingly calm in a crimson poncho.

How does she relate to bombings? “I like them,” she whispers. “But that’s not logic. That’s frustration.” Her eyes light up—the eyes of a wife who, while waiting for the voice of some digital employee of Con Ed or Bell, has put in her one hundred hours on the other end of a Hold button. “Bombings,” Patty believes, “hit the system where it shows. Everybody can see its regard for property over people.”

Be honest. Do you relate to the Consolidated Edison Building? When you first heard that the General Telephone Building got a little nick in its side, what did you say within your secret self? Goody? Right on?

At this point revolution-minded males, like Marc, and serious Women’s Liberationists, like Patty, part ideologies. Patty bought her copy of Jerry Rubin’s book in early March.

“Sure, I’d love to Do It,” Patty says. “But Rubin and Abbie Hoffman are sexists, they’re still looking up girls’ skirts. They’re still doing it to me. I can’t join their revolution. They want to do it the wrong way.”

On the wall of Patty’s study is a four-color school map of Africa. She would like to go there. In Africa, Patty says, there is no penis envy. Only vagina envy. In Africa God is a woman.

Marc must be at the commune’s free store by three. A health-food distributor, from whom the commune’s 30 families buy cooperatively, will be delivering the $400 weekly order. To each young family falls the task of varying the macrobiotic Basic Seven—brown rice, vegetable brown rice, rice cakes, Mu tea, salt plums and, for dessert, rice cream with honey—which all taste approximately the same. Like rice. They are not doing it for their health. They are preparing for anarchy.

“Most people refuse to deal with what might happen in a post-revolutionary period,” Marc says. His normally drifting speech pattern shifts abruptly. Words begin spinning out like Fast Forward on a tape recorder.

“If all means of production and distribution are blown out, people will be forced to make connections with their friends, to live and not starve. Groups like ours are learning to be self-sufficient. Probably there’ll be government as far as distribution of food goes … I’m fairly vague, too, I guess … but to me this offers more opportunity for people to find their true potential than sitting in tight apartments with their uptight jobs. Being pigeonholed in a tight State apparatus that controls the world.”

“What was that again, Marc? About the State apparatus?”

“State apparatus?”

“I’m not sure I got what you said about State apparatus.”

Marc’s laugh is a quick glottal release.

“I can’t remember what I say.”

That could be dangerous in Marc’s business. When he theorizes in the abstract and is confronted with a real-life example, Marc has been known to say: “I just changed my theory.” He speaks admiringly of his wife, even a bit in awe. Of the “politics of bombing” he can speak for hours. In the second person.

“You have a whole anarchist communist attitude now, not in the typical press sense of anarchist. Not anarchist capitalism, not the every-little-man capitalism of Norman Mailer’s campaign or Pete Hamill’s attitude. You have people who want a non-state government. It’s fine for where my politics are. What’s under all the repression, all the media lies and the parental lies, is people wanting to have relationships with people they really agree with. Non-coercive relationships.”

Is there any such thing? If so, why can’t people have them now?

Marc hesitates. He tells a little story about the girl he brought home recently, to experiment with communal love. Marc’s wife knew and liked the girl. But for some reason, when the three of them were in bed, a thought visited his wife. The one about being left alone with a child. Marc’s wife rolled away. The threesome went to sleep.

“I’m beginning to see almost all relationships as coercive,” mumbles Marc. “Though I do see a number of people who want to relate to one another…”

Spring. Movement buds are coming up at CCNY, Columbia, NYU, Pratt and at George Washington and Bronx Science high schools, for starters. Grass is for smoke-ins (primarily). The December Fourth Movement (D4M), formed after Fred Hampton was shot in Chicago, has work to do to get the faction-weary white middle-class revolutionary off his bleached jeans.

Friday the 13th of March:

Abbie Hoffman is orchestrating the biggest crowd at a Columbia rally since the Great April of ‘68—the first rally this year sponsored by the whole alphabet soup of campus political groups. Two thousand Columbia kids with cold teeth and a title to regain as the radical vanguard are gathering on the scene of former glories. Abbie, under the oxidized bronze skirts of Alma Mater, draws them all to his electric blue shirt.

Above him, the basilica of Low Library, carved in stone. The Royal Charter of George II stares Abbie in the back of the head.

KINGS COLLEGE says the stone.

BOOM says Abbie Hoffman.

Take it from there, Afeni Shakur. Afeni is the only member of the Panther 21 out on bail in New York. This rally is to raise bail for the rest, who were banished from Judge Murtagh’s courtroom for refusing to promise to behave. The Panthers’ black supporters pass hats and collect $400. But the white radical students have done their own thing. They have demanded, via resolution presented to the University Senate, that Columbia condemn the trial and come up with bail money for the Panthers.

Afeni wears big yellow hoop earrings and is galvanically beautiful. She tells the white students it is time for revolution in the mother country, not just struggle in the colony (meaning black America). She gives the students the extremes of choice they are looking for:

“If you don’t want a race war in this country, there’s got to be a class war!”

Cheering, followed by Jean Genet. A small, boring man in this setting. He speaks French, not rhetoric. The rally ends with a more incendiary speaker, on a note of suspended animation. The crowd herds up the steps—without plan, refusing to believe this is all there is—and breaks into a run in separate flanks around the carved stone of Low Library. A pale boy who says he is a poet is running alongside of me trying to quote himself about living in “this tedium of sickness” … but he is running out of breath. “Wow,” he says, seeing the crowd milling at the glass feet of Uris Hall, the business school, “they are going to have an action.”

Big Marv is waiting for the crowd. Waving them into Uris. He is a roving revolutionary adviser from the University of Wisconsin who sounds like Marlon Brando with a prexy’s education. Short and stocky in a brown leather jacket.

“Are you going to take Uris?” asks the poet.

“G’won in and find out,” Big Marv says.

It is old home day inside, 300 people from revolutions past and novitiates from the freshman class. One of the greats from ‘68, who is now writing a book on the revolution, as it happens, in serial form, for a radical magazine called Leviathan, talks about the recent bombings.

“I support them 150 per cent. They pinpoint the targets and strengthen the rest of the Left.”

Would he be willing to die for the revolution?

“Anyone who says they would is either crazy or lying.”

A pretty language-lab girl shrugs to a girl friend. “There’s nothing left in this university big enough to be worth fighting for this year.”

“Yeah,” says her companion, a senior. “Even last year we used to feel sorry for the freshmen because they hadn’t been here in ‘68 to see Kirk get guillotined.”

The tactical meeting has begun upstairs. Radical body fads are uninspired this year. The girls carry their pectorals a little lower, but under men’s-underwear T-shirts and hempy handwoven vests, who cares? The ones who still wear skirts to meetings haunch down in the chair and drape their booted legs—six inches apart—over the side. Defiantly liberated. They are always given equal time to speak this year. In fact, with Women’s Lib hanging over the men’s heads, even a rad-groupie can get behind the mike and in a moment of high radical fever, giggling as though just kissed for the first time, keep the mike while the men hush the crowd. White radical males still affect the intellectual slouch, a body fad developed at an early age to avoid football and get out of work. Although this year, coached by Newsreel’s films of Panthers bursting out of their bandoliers in iron-chested formation, the white male rad is standing taller.

Big Marv begins: “We as white people gotta show we’re not gonna sell the Panther 21 down the drain like white people always have before. Are we gonna sit in this building and become lethargic about our struggle?”

A terribly pretty boy with hair clasped in a George Washington pony tail addresses the group sideways, extending his hands through a WW I nurse’s cape.

“It’s fun to bust windows but it’s a drag to be in jail. We want to do things without going to jail. Why don’t we call a general strike because nobody wants to go to classes anyway and then we can do something beautiful while we wait for them to write the check.”

The check, which President Andrew Cordier is not really expected to write, is for $1.3 million bail.

A white girl wearing the Panther beret tries to bring the crowd back to the issue. “We’re here to get up Panther money, aren’t we?”

“… ‘It’s like assassinating a President. You shake his hand and a bomb goes off. It isn’t difficult if you’re prepared to die.’…”

The hard core no longer bothers to answer questions like that anymore. The issues are not answers anymore, the Panther bail is a prop. What really matters in this room is the tactics. (Another Rubin chapter head has been digested: “I Agree with Your Tactics, I Don’t Know About Your Goals.”)

A speaker announces he has just been handed a note by a man who quickly turned his face and ran off. The speaker says it is pertinent:

To Students at Columbia:

This week we blew up three office buildings owned and operated by the biggest death institutions in this country. Andrew Cordier is on the Board of Directors of two. Today Columbia students have taken action. If you think that will put on the heat, do it, but understand that people are sick of Columbia. We understand three affinity groups have been formed at Columbia. We must take down enough so all the King’s horses and all the King’s men couldn’t put it back together again. Those who are ready should do as we have done. Organize in small groups with people you trust and tear down the walls.

—Revolutionary Force 9

Now there is much applause and the talk moves to formation of affinity groups, rock-throwing as a tactic, a proposal to send a task force out to Ferris Booth Hall to see if the occupation can be transferred there. As the base of operations for the weekend.

A report comes back from the Senate on the bail resolution. Defeated.

“Let’s trash the building on the way out!” shouts a sideliner. The house is divided. Big Marv makes a difficult decision. He advises that the building not be trashed.

In those glum hours between rallies, the intestines of competing, incipient leaders churn. Big Marv sits alone outside the Lion’s Den, receding into a bank of mirrors. A small freshman boy spots him.

“You should have trashed the building on the way out. You needed to get those non-militant people hungry for action.”

“Yeah,” says Marv. “We shoulda trashed the building.”

By nine at the Sundial, Big Marv is in punching form.

“I’ll make this brief. You gotta speak to the Man in the language he understands. We’ve gotta use the language of rocks and the language of guns. We heard a great man named Hoffman today. He has a friend named Rubin. And what was the name of Rubin’s book?”

“DO IT!”

“Now, how many midnight raiders have I got in the crowd?”

Big Marv leaps off the Sundial in a mid-air run.

That night two hundred, maybe three hundred—people and press spend hours arguing about the numbers later—smashed the glass of the ruling class. And waited to see how many liberals liked the noise.

Marc walks down Morningside Avenue in his Army surplus jacket, but his cop-out from military service is no comfort. He didn’t even burn his draft card. Just refused to go to ROTC. “It wasn’t an anti-military thing. I just refused to keep my shoes shined.” When he was bounced from his first college, a friend got him into a Midwestern school where his roommate was a self-styled Communist. The largest influence on Marc’s swing leftward, the Communist is now divorced and hunting—literally checking out applicants all over New York—for a Japanese girl to serve him. “A most extraordinary chauvinist,” as Marc speaks of him now. But in Marc’s face, when he talks of the Communist, the down lines pull up and his mustache spread-eagles over a smile.

“I have this almost complete disgust for his ideas, and at the same time … this almost love for him.”

At the edge of Morningside Avenue is a black iron fence. Marc looks over the rim into the bowl of scrapgray buildings called Harlem. In them live the scrap people whose walls are cemented with sand and roaches and whose streets are pop-up garbage pails. Marc is beyond the reaction of knee-jerk irrelevance. Fenced in on all sides. What options are open to a self-respecting Jewish radical these days? Can he be happy as a Scarsdale dentist? Medicine, law, government advisory service—the traditional fields are tainted ruling-class blue. The dress business? One must employ workers. Become a worker? Say, a waiter at Ratner’s. Has anyone seen an angrier man than a Ratner’s waiter?

Marc is bombarded by feminists for being a male sexist … by his parents for not being Norman Thomas … by the Panthers for not being black … by PL for not getting chummy with cafeteria workers … by ultra-militant friends for not being Ready To Die. Scorned on all sides for not being poor enough, liberated enough, violent enough, Marc is deprived of being genuinely deprived.

Perhaps never have Americans, particularly New Yorkers and most especially white-middle-class radicals, been more free to create a private life style. White boys can wear Afros, black men can be hippies. Liberated women can lock editor John Mack Carter in the Ladies’ Home Journal bathroom and tell their tale on the tube … Jerry Rubin smokes pot on Channel 11 … marriage is something hip parents try to talk their 23-year-old daughters out of (“Why don’t you live with him for a while, dear?”). Communal living, denounced only two years ago as the final depths of our moral anarchy, received the kiss of a Life magazine cover last summer. Vermonters took communal livers to their hearts almost immediately, drawn to their flinty individualism and respect for privacy. At this rate John and Yoko could probably do it in the road by next Christmas. While eating a hamburger. This is oppression?

At the same time, for real reasons beginning with the shock of John Kennedy’s assassination in continuous performance on TV, Americans have struck up a romance with civilian death. The Woman of the Year is most likely to be a widow—Jacqueline Kennedy, Ethel Kennedy, Coretta King, preferably an assassination victim’s widow, though just a widow will do. This year it will probably be Rose Kennedy. Rich white brain-laden students idolize black radicals because they have plausible reasons to die. For some young white radicals it is enough to participate in the chic of rage and the ecstasy of despair. Moments after the excitement of trashing Columbia, a radical student found himself sitting in another tactics meeting. He dropped his head into his hands. “We’ll never have a revolution in this country. Too many people are happy.”

Other students, often our best, feel they cannot make do with less than “that absolute friendship, without reticence, which death alone gives,” described by Malraux in Man’s Fate. Though he writes of Communist revolutionaries in China of the twenties, the appeal of death for a cause is trans-cultural, trans-ideological.

“… a doomed life fallen next to his in the darkness full of menaces and wounds, among all those brothers in the mendicant order of the Revolution: each of these men had wildly seized as it stalked past him the only greatness that could be his.”

America’s black man has not had the freedom to be given, and to refuse. He is claiming it now. America’s rich white children—dissected, scolded but always adored—have not had the gift of sacrifice. They are asking for it now.

The degree of sacrifice becomes more extreme, a condition the white radical works very hard to create. As Marc says, “Weathermen, D4M, any anarchist group, couldn’t care less what happens to the Moratorium Committee or the Fifth Avenue Peace Parade Committee. They’re never going to do anything revolutionary anyway. If these groups are smashed, it gives people on the fence an even clearer choice.”

The affluent insurgent is cutting down his own choices at the same time. Not content to rain on other white people’s parades, he is more impatient than the blacks. “While the Panthers have tried to broaden their base in the black community and win flanking support outside of it,” writes Washington Post columnist Nicholas von Hoffman, “the rich, white revolutionary terrorist has, through arrogance, absolutism and a recklessness that makes him very dangerous to be around, isolated himself until he has run out of choices: he can give up politics or become a clandestine bomb thrower.”

Says Jerry Rubin: Amerikan youth is looking for a reason to die.

This is one of the questions I ask myself these days: Is bombing a white male ego trip?

Curious how rock-throwing as a tactic was introduced to the Left just last summer by the all-white middle-class Weathermen. At Dupont Circle in Washington, as pre-emptive warmup for the November Moratorium, they threw bricks. Next Weathermen went on work-study programs with adolescent street gangs in the ghettos of Chicago and Boston. To boil their own politics down to instinct: Us vs. Pigs. Live vs. Die. You can’t be Hamlet in the ghetto, baby. Teach me tonight, little black brutha. Squash those honkie brain cells. Get the current running from gut to fist.

While the white Left waits for the Panthers to get out of jail and give them instructions, the white ultra-rads are experimenting with dynamite and nitroglycerine. Cleaner fighting through chemistry. The fists and guns of street fighting are not the white radicals’ favorite things. Face-to-face combat means somebody goes home crying. Or dead. Why not leave those tactics to the blacks? They’ve had practice, after all, fighting their way up from under.

Bombing, on the other hand, is a hit-and-run operation. Like rape. Both appeal to those who feel impotent and seek their lost power on dark streets, running.

This is the question Marc asks himself every day:

“If the script calls for blowing up something or killing someone, can you put that above your own life? If the answer is yes, it’s just a question of getting your head straight so you can do it. It’s like assassinating a President. You just shake the President’s hand and a bomb goes off. It isn’t difficult if you’re prepared to die.”

He still uses “you,” not “I.”

After many hours of talk and three months of preparation, Marc is still preparing to die. In the second person. For the time being.

Forbidden Games

Do It, Scenarios of the Revolution, by Jerry Rubin, will probably be the most widely read unassigned text of the year. Even before its official publication on March 30, Columbia’s Paperback Gallery couldn’t keep it in stock. The publisher has already committed to print 160,000 copies. The only existing advance review is from the Virginia Kirkus Service, offered to libraries. According to the Kirkus Service, some of the book is funny, except for the last chapter—”that’s scary!” Right on, Virginia!

The true brilliance of Rubin’s book is that it makes fools of everybody, starting with his agents, his editor and his publisher, Simon and Schuster. A very straight outfit.

Jerry says in his book that revolution is profitable, so hip capitalists like to sell it. He’s right on again.

Rubin explains it very simply in his book. “Beware the psychedelic businessman who talks love on his way to the Chase Manhattan Bank.”

“A Hip Capitalist Is a Pig Capitalist.”

Carl Brandt, Rubin’s agent, is on the phone. I read him a page from Jerry’s book. Does he consider himself a Pig Capitalist? He laughs, thinly.

“No, I’m just doing my thing, which is being a literary agent.”

“It was a conventional narrative when I first saw it,” explains Rubin’s editor, Daniel Moses. “Jerry started shortening the sentences. Then he decided it should be treated graphically, with a combination of pictures and cartoons.” Quentin Fiore, who designed McLuhan’s The Medium is the Massage, was hired to subvert the type. Next … Eldridge Cleaver for the introduction. “I had no problem convincing Simon and Schuster to use Cleaver’s introduction,” says Moses, “and to pay some good money for it.”

Here comes the OK sign from Algeria to Babylon …but first, Eldridge has to give Jerry the quick, bloodless clawmark that all guilt-dragging honkie rad readers have come to love.

“The first chapter of Jerry’s book is entitled Child of Amerika. That’s another one of Jerry’s trips. It is impossible for him to be a child of Amerika … He is a descendant of the invaders.”

But! The ritual wrist-slapping over, Cleaver actually gives the OK sign to our Yippie hero . . .

“I can unite with Jerry Rubin around a marijuana cigarette … around being cool … I can unite with Jerry around hatred of pig judges, around hatred of capitalism, around the total desire to smash what is now the social order in the United States of Amerika.”

… and all of a sudden a whole nation of high school kids with sensitive white skins can relax.

Be a Yippie. Ride the Panther handlebars. Forget Marx and his old long ponderous words. You don’t even need to be able to read! Lookit the pitchas.

The really new politics is a comic book.

If you’re reading stoned, as Do It suggests—but a little over-stoned so that your eyes are jumping around, you know—then get your mummy to read you to sleep with the last chapter: “Scenario for the Future.” She’ll get a real bang out of it.

Every high school and college in the country will close with riots and sabotage.Yippie helicopter pilots will bomb police positions with LSD gas.Revolutionaries will break into jails and free all political prisoners.Kids will lock their parents out of their suburban homes and turn them into guerrilla bases, storing arms.

Who would ever take a thing like that seriously? Except a high school kid. As Rubin’s editor says, “We haven’t even reached our primary market yet—the high schools.” Right on! Some primary market creep reads the book. Or maybe a junior high groupie. She tells her friends about the last chapter … all those Miss Weather plastic color-form kids with their press-on clothes. Put it together with the politics of prerationality and what have you got? A Mattel war toy. —G.S.