On a short flight to New York recently, I was sitting behind two white, well-dressed twentysomethings chattering loudly and uninhibitedly about going to clubs and travel plans and the possibility of living in New Jersey. Then came the question: “So who are you voting for?”

“I was for Hillary, but now … I’m kind of undecided,” volunteered the first woman.

“Are you a Democrat?” asked the second.

“Yeah. But I think I might go with McCain. It’s just that, well, I don’t know. You know.” Her voice dropped. I leaned forward to hear better. “You kind of hate to say it aloud, but … ” Here her voice dropped again, to a murmur lost in the roar of the jet engines, and I missed whatever came next.

Let’s start with this concession: I have no idea what that young woman actually said. In a perfect world, I suppose that would be the end of the story and I would go back to minding my own business. In the context of contemporary political discourse, however, it did cross my mind that if this conversation were presented on one of those “finish the sentence” cultural-literacy tests, then pretty much every American, of whatever creed, color, or class, would have exactly the same guess as to how the woman completed her thought.

I think there’s some consensus, in other words, about the one thing in America we really “hate to say” aloud. Yet by refraining from saying audibly that-which-must-not-be-spoken, was the young woman’s political choice rendered rational, neutral, pure? Conversely, if I were to spell it out here, would I be the one accused of “playing the race card”?

This is a complicated monkey wrench in our supposedly post-race society. On the one hand, everyone knows that race matters to a greater or lesser degree; on the other, few of us want to admit it. Indeed, race is the one topic that’s probably even more taboo in polite company than sex. Yet in the absence of fact or frank conversation, grown people get buried in the kind of whispered fear, fantasy, and ignorant mistake that a 5-year-old makes when explaining how icky it was when Daddy got Mommy pregnant using the garden hose and a large bowl of avocados. Is this misinformation really so different from when Fox News and Karl Rove fill in the blanks of those awkward silences with images of the perpetually pantyless Paris Hilton rocking the foundations of our civilization on the same stage as Barack Hussein Osama, oops, I mean Obama. This is racial pornography that exploits the barely suppressed caverns of imagined horrors that have haunted us since D. W. Griffith’s Birth of a Nation.

Obama predicted this phenomenon and attempted to expose it to the anodyne of common sense: “They’re going to try to make you afraid of me. ‘He’s young and inexperienced and he’s got a funny name. And did I mention he’s black?’ ” The not-altogether-surprising backlash from McCain’s campaign is a deflection, an expression of deep discomfort. The reflexive accusation that Obama was playing the race card has a certain resemblance to the juvenile retort one gets when the science teacher tries to explain the human reproductive system: “Ooooh! He said a dirty word!” In this way, the opportunity for thoughtful public analysis sinks, once again, below the sound of the audible. Yet the fear of race rolls on, pantomimed in palpably influential and consequential ways.

At the same time, the civil-rights movement has given us a moral conscience that was not as prevalent when The Birth of a Nation was made. Today, it’s fair to say that the overwhelming majority of white Americans “hate to say it aloud” because they also hate to think of themselves as racists. But blacks and whites tend to differ in their very definition of racism. Some years ago, researchers conducting a study for the Diversity Project, at UC Berkeley’s Institute for the Study of Social Change, asked black and white college students about their perceptions of racism on a given campus. White students tended to say there was none, but blacks and Native Americans said it was everywhere. In fact, the study documented an interesting phenomenon: As Diversity Project sociologist Troy Duster put it, “White students see diversity as a potential source of ‘individual enhancement,’ ” while African-American students were more likely to see the goal as “institutional change.”

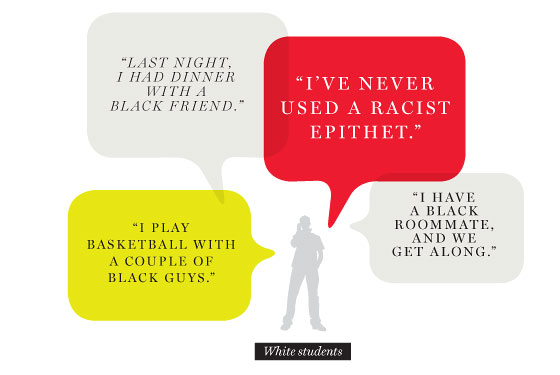

When the white students were asked to give illustrations that substantiated their positions, they spoke of their own experiences and of personal intentions. “Last night, I had dinner with a black friend,” they might offer. Or, “I have a black roommate, and we get along”; “I play basketball with a couple of black guys”; “I’ve never used a racist epithet”; “I treat everyone the same.”

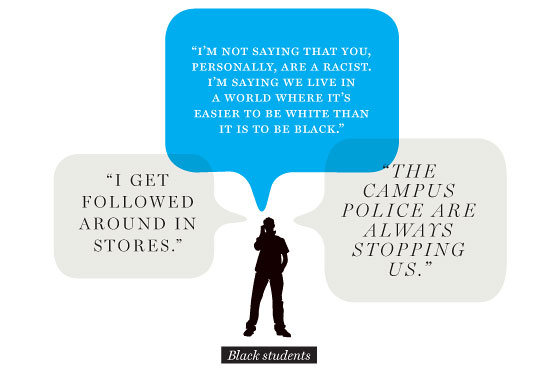

The black students cited instances of relative privilege, things that were more structural, institutional, atmospheric. “The campus police are always stopping us”; “I get followed around in stores”; “Most of the white students don’t have to think twice about how much it costs to take prep classes for the LSAT or to spend spring break skiing in Aspen or partying in Cancún.”

It’s a familiar, even ubiquitous, miscommunication over the last ten years of the so-called culture wars: A black person speaks of racism or white privilege. The nearest halfway-privileged white person protests, “But I work for liberal causes. You’re lumping me with racists just because I’m white!”

The black person answers, “I’m not saying that you, personally, are a racist. I’m saying we live in a world where it’s easier to be white than it is to be black.”

“But I’m not part of that,” comes the reply.

“We’re all part of it,” insists the black person.

The tendency to turn the commitment to racial liberalism into sheer denial is strong. “I don’t see race” becomes “I don’t see racism.” But while some of us are listening to the soothing tones of National Public Radio, a much larger audience—and larger by millions—is listening to Rush Limbaugh singing those subterranean fears of “Barack, the magic Negro,” or to radio shock jocks cackling about “jigaboos,” or to Pat Buchanan fretting that Obama is a radical, unpatriotic, extremist “elitist” to whom the liberal media hands a pass as a “special-ed,” “affirmative-action” candidate. Not that any of them mean it in a racist way. Hey, lighten up. Don’t you have a sense of humor?

Then there are the real-life, on-the-ground, disastrous statistical disparities that burden the lived experience of the majority of blacks, people of color, and the poor in this country: from the still-unrepaired wake of Hurricane Katrina, to the greater infant-mortality rate and lesser life span, to near double-digit rates of unemployment, to cuny professor Harry Levine’s study of stop-and-frisk statistics in New York City (blacks are eight times more likely than whites to be stopped for marijuana possession, for instance), to disproportionately high national rates of foreclosures and homelessness among blacks, Native Americans, and Latinos, to the almost complete resegregation of schools across the land, to a war on drugs so shockingly racialized and so aggressively executed that our rates of incarceration place us first in the world.

There is an interesting kind of cognitive dissonance at work in the American psyche. We rejoice in the warm symbolism of interracial bliss, particularly in the idealized and thoroughly mythic sphere of celebrity existence: Tiger Woods’s Pan-racialism, Brangelina’s adoptions, Steven Spielberg’s handsome brown son. We tell ourselves we love the idea of diasporic enfoldment: bi-, tri-, and multiracial Kids ’R’ Us. At the same time, there’s terrible ambivalence on the ground. Does one really want “the race card” living next door, or being your boss? Do you really want your child marrying outside his race? I’ve had conversations with white friends who are rattled when a black classmate has bested their child in class rank but still can’t let go of the feeling that the mere presence of blacks in the school must be bringing down the test scores.

Similarly, it’s interesting to review the evolution of media commentary, from TV to the blogosphere, trying to fit the thoroughly unfamiliar Obama into familiar boxes. For a while, he was depicted as not having any “racial baggage.” Then, in the blink of an eye, he was transformed into Exactly the Same Person As the Reverend Wright—who then could be demonized with all the well-practiced repertoire of insults reserved for Louis Farrakhan and armed revolutionaries.

Obama’s comeback, his eloquent speech about race, showed that he wasn’t exactly the same person, not by any means. So in yet another twist, he is now so uppity he needs bringing down, defamed as too famous, categorized as uncategorizable, displaced as unplaceable. Since, in actuality, more is on the record about every step of Obama’s life than possibly any candidate on the planet, this particular brand of demonization has been accomplished by the insinuations of erasure: If you took away his “pretty words,” he’d be nothing. If you took away his race, he’d be nothing. If only he didn’t have a brain, he’d be nothing, nothing, nothing. It’s a circular, nonsensical mantra—magical thinking, wrapped in the fiction of “but really, I never see race.” This kind of denial masquerading as color-blind idealism cannot be our compass at this exciting and potentially transformative moment.

• Heilemann on the Color-Coded Campaign

• The Racial Politics of the Obama Marriage

• How the Obama Generation Will See the World