From the December 23, 1968, issue of New York Magazine.

Toward the end of Gore Vidal’s gossipy, underrated novel, Washington, D.C., a fictional girl named Elizabeth Watress meets President Truman at a Democratic Convention. She is tall, beautiful and well-bred. (In fact, her whispery voice, a divorced father who “played polo and drank heavily,” a public manner “simulating fear and delight in equal proportions,” and her eventual marriage to a handsome young Presidential-hopeful have led a lot of people to think she is based on Jacqueline Bouvier.) So it surprises Clay Overbury, her eventual husband, when she gazes after little homespun Harry Truman with whom she has just shaken hands, and exclaims, “‘He looks so sexy!’”

“‘Sexy? Good God, you are crazy. That’s the President.’”

“‘And that’s what I meant,’ said Elizabeth evenly, and Clay laughed. Not many girls were so honest.”

If Harry Truman had pursued this advantage (he didn’t; even Gore Vidal doesn’t go that far), he certainly would have known that it wasn’t his beautiful soul and/or body that attracted her. Men wise in the ways of power understand its sexual uses as well. But there are a lot of men, and a surprising number of women, who believe the sexual segregationist argument that women aren’t interested in power at all; that something in their genes makes them prefer to be ordered about. While this is true of individual women—and some individual men: think of all those who seek out domineering wives or job hierarchies to take orders from—it turns out to be no more fundamentally true than all the other past myths: that women enjoyed sex less than men, for instance, or that Negroes were dependent creatures who didn’t want power either.

A century ago when Henry Adams wrote Democracy, still the only truthful novel about American politics, he understood that women wanted power, and had quite good instincts for using it. But objective truth and social truth are two different things. As a shy pretty Barnard girl explained, surprised to find herself braving police cordons outside a Columbia building, “I guess I’m just finding out that women are people.”

New York is probably one of the better places to discover it. Girls come here, after all, for somewhat the same reason that Negroes and homosexuals do: to escape the roles dictated by their background and Conventional Wisdom, and discover what they can do on their own. Frequently, it turns out that they, too, want to see tangible and intangible proofs that they make a difference in the world, that they are unique and valuable people. Power may be a dirty word, especially among New-Left-through-Hippies who fear that it must be manipulative and bad. (Though they have no double standard. Power is bad for anyone, male or female, and “manipulative” is the worst word in the New Left lexicon.) But vitality and a desire to change things are its ingredients, and the under-thirty generation has those in better supply than anyone else. They may not call it “power,” but they are certainly seeking to take control away from the Establishment.

Nobody seems to be denying the biological differences, not the Barnard girl, nor those few women in New York who already wield some power. (“You lose interest in everything else for a month or so before childbirth, and several months after,” explained a former State Department official, now a political science professor. “Nature takes care of that. But the women I see who continue that singlemindedness year after year because they think they ought to—they end up being a burden to the child.”) It’s just that the difference is less all-pervasive than it was in the under-populated day when women had to have a lot of children (and spend all their time running a complicated household) if a few were to survive.

Now, motherhood, like sex, dominates a woman’s life only by its absence; nothing else may go very well without it, but once that basic need is being fulfilled, there’s still a lot of life and interest with no place to go.

But the fact is, even in New York, that the great majority of women don’t have the training or opportunity or courage to get and use power on their own. Probably, they’ve been brought up to believe that such ambitions weren’t feminine. (And if any group is told its limitations long enough, pretty soon they turn out to be true.) Those who hold jobs of any influence—unless they’re totally concerned with makeup, clothes, cooking, and the like, and have no men in the hierarchy under them—are eventually gossiped about as pushy and masculine even now. (“What can I do?” said an unmarried representative of a fashion house who is often thought to be a lesbian. “I can’t sleep with every man who thinks that just to disprove it.”) It’s the same kind of emotional blackmail that used to keep men out of the arts, and push them into various forms of social violence—hunting, street fights, sports and wars—whether they liked it or not.

To accuse someone of not being a “real man” or “real woman” is a potent social weapon in preserving the status quo. During each war, women discover that they can do “masculine” jobs and wield power without losing their femininity, and after each war, they are sent back home (though there are always some who won’t go: wars have changed women’s status more than any suffrage movement) by men who return with standards unchanged.

Even those who keep their jobs are often apologetic about it, insisting that they just work so the family can have a few more luxuries; an easy way to avoid disapproval that might come from admitting they liked the independence, and even the power. In the women’s-rights movement, one of the few instances of taking this emotional blackmail head-on came from a distinguished Negro freedwoman named Sojourner Truth. “Nobody ever helps me into carriages or over puddles, or gives me the best place,” she said, letting a male critic have it between the eyes, “and ain’t I a woman? I have ploughed and planted and gathered into barns—and ain’t I a woman? I have borne thirteen children, and seen most of ’em sold into slavery, and I cried out with my mother’s grief—and ain’t I a woman?”

That was more than 100 years ago, and now, women are defensive about commanding office staffs, much less ploughing.

In fact, they don’t like to admit the barrier between men’s jobs (those with power) and women’s jobs (those without). It’s sort of embarrassing, and may lead to such dread accusations as being a feminist. (An associate producer of a television talk show, who has now seen five not-very-well-qualified men promoted to be her producers, one by one, while her capabilities are ignored, complained to a station executive. “He thought I was getting ‘women’s rightsy,’” she said sorrowfully. “Couldn’t he at least say human rightsy?”) But in New York, where hierarchies are probably more modern and flexible than the rest of the country, the barrier still exists. It seems impossible to find a profit-making organization of any size that doesn’t discourage women, subtly or not so subtly, from aspiring to positions of any power.

In banks, female “senior tellers” and male “vice-presidents” often do exactly the same job, but salaries and promotional possibilities are as different as the titles. At Time Inc., men write, edit and get promoted; women research and then research some more. Television has women with “associate” and “assistant” in their titles, but almost none (outside public service and kiddie programs) are allowed to be full-fledged writers, producers, and directors. The New York Times employs more women than Negroes (“Only because,” said one disgruntled newswoman, “we have a Women’s Page and no Negro Page”), but they are no where to be seen in Editorial Board lunches or the decision-making process. Women are illustrators but rarely art directors. J. Walter Thompson and other big advertising agencies don’t encourage women account executives “because the client might not like it”; the advertising successes of Mary Wells and June Trahey not withstanding.

Politics is probably the worst of all. Even Robert Kennedy couldn’t help Ronnie Eldridge, an eminently capable young politician who was then a District Leader, into the job of New York County Leader once occupied by Carmine de Sapio. Kennedy thought she could handle it well, but the Reform Democrats hesitated, largely because they didn’t want a woman.

Sometimes, women do well outside an organization, or by starting their own business, but in general, they just aren’t considered eligible for power. Caroline Bird, who has done the best book on this barrier, Born Female: The High Cost of Keeping Women Down, comes to the conclusion that powerful women—like Mary Wells or Judge Constance Baker Motley; or even Geraldine Stutz of Bendel’s or Mildred Custin of Bonwit’s, though fashion merchandising is traditionally a field more open to women—have gained their positions because of loopholes and idiosyncrasies in the system, not because of any liberated attitude in the system itself.

In 1944 when he wrote The American Dilemma, Gunnar Myrdal added a parallel between women and Negroes. Both groups, he noted, had been slowed down by the same crippling stereotypes: smaller brains, childlike nature, limited ambition, limited skills, roles as sex-objects-only, and so forth. Neither group liked the comparison very much, but now that Negroes are throwing off these stereotypes so insidious that they themselves had sometimes believed them, women are beginning to think twice about the similarities, in kind if not degree.

Of course, the big difference is mobility; even in work, women have more leeway, and socially, their mobility is almost limitless. Sponge-like, they acquire the status (even, temporarily, some of the power) of the man they’re with; so much so that it’s part of every girl’s experience to be treated as two entirely different people just because she’s changed escorts.

To make this acquisition of the ruling group’s privilege and power more or less permanent, all women have to do is marry it. The method is simple, socially approved and sometimes even happy. Women have been doing it for years. Of course, this practice makes for June-January matches: figuring out a man’s power-potential when he’s still in his 20s isn’t easy, and an important older man usually expects a wife to be young and to look good; that’s her part of the bargain. (New York is full of this sort of marriage, from the short bald men and tall blonde wives in the Stage Delicatessen to distinguished lawyers and Vassar graduates on Sutton Place. Washington would be even fuller, if only politicians could get divorced.) Marrying for power is slightly more evolved than marrying for money and doesn’t get boring nearly as fast. The wife must have had some dim appreciation of her husband’s work, after all, in order to figure out how powerful he was in the first place. They may even be working together, though never on an equal basis. (Secretaries marry executives, students marry professors, researchers marry television producers; it’s a giant step, an Instant Promotion.) Only Helen Gurley Brown has grasped and openly written about the idea that office proximity is to the making of “good” marriages what social connections and dowries used to be.

The bargain, if both parties are clear about it, may work out well. The man gets the pleasure of a new and admiring audience for his power displays, and the wife has the exhilarating experience of being on the Inside; a place she would never be allowed by herself.

Moreover, she herself becomes a power symbol: youth and beauty well displayed. Sexually and even financially, her husband may view her that way. The sales people at David Webb, the jewelers who have a genteel air of having seen everything, nod solemnly at arguments like (one woman to another hesitating over $18,000 earrings). “It’s a wife’s duty to be a showcase for her husband’s power and success.”

Unfortunately, the man—believing the convention that women aren’t interested in power—may assume she loves him for himself. There isn’t much excuse for this considering that he has probably used power calculatingly in order to attract her. (It’s a standard part of the New York mating game for men to have girls pick them up at the office, whereupon they push every button and issue orders to every employee in sight. Lunch in executive dining rooms, police escorts on the way to the theatre, celebrities produced for all occasions, a personal wine cellar at one or several restaurants: all this heavy artillery may be brought out for the wooing.) But it still comes as an unpleasant surprise to many men when they produce three Broadway flops in a row and their wives’ affection cools; or when “the other man” turns out to be someone older, less attractive, but more powerful; or when they retire to long-¬anticipated lives of comfort and leisure, and their wives want a divorce.

They are even surprised, if not quite so unpleasantly, when their wives try to exert power through them. The simplest form is the marital “we” (as in “we just bought a big British company,” or “Bernstein is doing our symphony,” or “we knew we should have re-written the second act”), even though the wife has had nothing to do with it. This taking of unearned credit is as ridiculous (especially when spoken by the 22-year-old wife of some hard-working man) as it is popular.

A more combative form is two such noncontributing wives competing, with or without subtlety, about whose husband is the more powerful. The air at chic restaurants is thick with such gamesmanship every day when ladies lunch. (This bears a great unconscious resemblance to nannies and other servants who compete about their families’ wealth; except the servants have usually worked harder and deserve to brag more.)

Finally, there is the wife who tries to make her husband’s power her own, who wants to select the companies he buys, or the scripts he produces, or the political strategy he campaigns with. She is much more admirable (at least she’s trying to earn some of the credit she’s taking), but if ability doesn’t go along with desire to influence, she may be the most destructive in the end. There are always stories in New York of talented husbands who haven’t got this or that job because they come as a package with interfering wives. The name of one movie producer gets groans from directors. His wife insists on showing up to interfere at all production meetings.

The wife looking for power and the husband who has it are dependent on a lot of outside circumstances at best. But the difference between public and private conclusions about women and power comes out in odd ways.

In Washington, for instance, it was a much-discussed fact that many of the men around President Kennedy got divorced when the Administration ended. Most men assumed that the husbands had wanted out all along, but refrained from leaving because the publicity would be bad. Many of their wives, who worry about what their lives would be like should their husbands leave, assumed the same. But several of the hostesses and one woman high up in the State Department—some of the few in Washington with identities not dependent on marriage—wondered if the wives hadn’t had something to do with it. “Why stay?” as one hostess said. “The Kennedy court was obviously their high point. Better get out and find some other interesting man fast, because it’s going to be straight downhill.”

Few wives, even if they have made power marriages, are that clear-eyed about it. Going along with the women-aren’t-interested-in-power theory, they may assume that they couldn’t possibly be, and therefore the attraction they feel must be something else. Power translates into sex, and admiration into love. But power and sex are only the same in anticipation, so the wife—who still feels her own power urge satisfied through her husband—may find herself having an affair with a more ordinary man, without any thought of leaving her husband. That’s the lady married to a bigwig who goes out with her garage attendant on the side.

If she loves him, or is convinced that she does, she often finds herself jealous of the work whose results attracted her in the first place. Political wives who rarely see their husbands except on national holidays and campaign planes; business wives who get tired of having all birthday and Christmas gifts selected by secretaries; every wife of a powerful man who finds she can get anything except his attention: life and fiction are full of them.

“Never marry an important man,” said a girl who observed all this from her vantage point as secretary in the White House. “Go out with them or have affairs with them, but find some other kind of husband.”

According to Alice Roosevelt Longworth, even Eleanor Roosevelt didn’t always enjoy her position. On hearing of her husband’s first election to the Presidency, she is supposed to have run from the room in tears, and said, “Now, I’ve lost my identity.” One New York woman complains that people she has had dinner with don’t recognize her the next day in the street without her husband’s famous face. A woman who marries a powerful man gets an instant identity all right, but it’s his.

Still, acquiring power through men remains the only sure-fire acceptable way. Margaret Mead notes that this society approves women’s power only if it’s been inherited in some sense, and that widows of admired men are therefore the only women leaders to be widely accepted. Inheriting a seat in Congress is liked, but winning it is not. The activism of Eleanor Roosevelt won more affection and less resentment after the death of F.D.R.

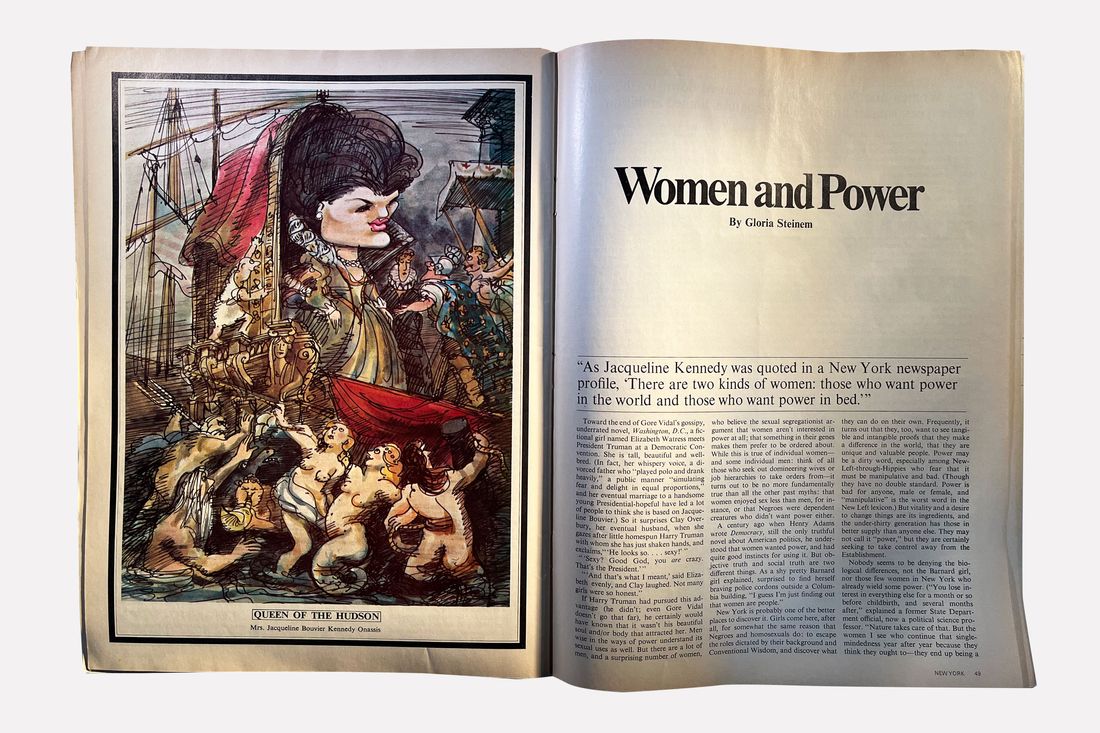

Even Jacqueline Kennedy, regarded as ornamental but frivolous before her husband’s death, got all kinds of serious suggestions that she become Ambassador to France, or even Johnson’s Vice President, immediately after. But as she was quoted in a New York newspaper profile, “There are two kinds of women: those who want power in the world, and those who want power in bed”; the clear implication being that she was the latter. And, almost equally clear, that she disapproved of the former.

Some women solve the problem of being limited to one husband’s identity by having several. One New York widow is said to have married once for money, once for power, and once for social standing, so that she emerged, if not as herself, at least as the author of an anthology. She fell somewhere between Mrs. Kennedy’s categories, but then so do most women. Sexual power may be enough by itself. (As in the case of girls who enjoy conquering powerful men, and thereby making them pathetic and human. “It’s hard to explain,” said one television actress, who was having an affair with a much-feared Texas business executive, “but seeing him pad around in shorts to bring me breakfast, or knowing he’s switching the schedules of millions of dollars and hundreds of lives just so he can get to New York and see me—that gives me some feeling of accomplishment.”) Or it may be a direct path to worldly power, as in the case of many girls who marry for it, or get jobs and favors as the result of affairs. But it’s rare that the excitement and rewards are totally detached from the outside world.

“Sex,” said an English historian, “is woman’s only path to power.” As women’s options increase, that’s not much more true than, “The way to a man’s heart is through his stomach.” But it is likely that, as long as power is seen by some women as a peculiarly male attribute which only men can confer, they will go right on confusing sex with power.

It’s no accident that politicians have to devote less time and trouble to the seduction of women than anyone, possibly including male movie stars. And it’s no accident that political conventions, not to mention White House workers of almost any rank, are surrounded by dozens of otherwise well-bred girls who are strangely willing.

As Arthur Koestler wrote, quoting a European woman who was interested only in important men, “It’s like going to bed with history.”

The power-through-men theory can produce very constructive marriages and good partnerships. One of the best examples is Clementine Churchill, who simply made a decision when she married young Winston, not yet a leader of any kind: she would devote herself to him totally, to the exclusion of any separate life of her own, and chances of the couple’s success in the world would depend totally on his tastes and decisions. Mrs. Leland Hayward, an adopted New Yorker who was married to Sir Winston’s son, the late Randolph Churchill, believes that this investment of time and loyalty had a lot to do with Churchill’s later power and success.

“Clemmie never did many of the things that other wives enjoyed—dinner parties, going out with her own friends; anything—unless it happened to be part of her husband’s life, too. His friends were hers, his enemies were her enemies. I think that unquestioning support did a lot for him, especially during the middle years when his career seemed to be over. I wonder about a man like Duff Cooper [a diplomat and a wartime Cabinet officer]. He was very intelligent, very talented. His wife was a good wife, but she wasn’t interested in politics, and so tended to have her own dinner parties and activities. Would he have been more of a force had his wife been like Clemmie? I don’t know; it seems possible.”

But, as Mrs. Hayward also observed, this kind of devotion doesn’t always get rewarded these days. “Too many first wives,” she said, “find themselves exchanged for younger ones when the lean years are over.”

Certainly, the number of divorces right out of medical school, with men no longer interested in the girls who worked to help put them through, has become a kind of joke around colleges. Very few women find themselves married to a man of potential power, much less greatness, whether they can recognize it or not. But this kind of partnership is still possible, and may contribute to the rise of a powerful man.

Whether out of love and devotion or cynicism and necessity, the truth is that most women will have to exercise their much-denied but very much alive instincts for power through men for a while yet, at least until the generation now in college starts taking over the control centers. Young girls are refusing to be emotionally blackmailed into domesticity in the same way that boys no longer fall for the real-men-go-out-and-fight tradition, but the change will take a long time.

Because women don’t have power in this country or this city except as consumers. (Which is exactly parallel to a voter’s power to run Washington. There is a choice between candidates, or among brand names, but very little influence on what’s presented for that choice.) Or as a nuisance. (Large numbers can occasionally make enough noise so that men act just so the noise will stop.) The myth of economic Momism that grew up in the ’50s—based on women’s new consumer power, and the rise of Madison Avenue—is, when it comes to real power and control, just that: a myth. Women make, have, and inherit a great deal less money, and what they do have (even the greatly exaggerated number of rich widows) is usually controlled by men. They do very poorly at getting into the knowledge elite. (Nine per cent of professors are women; six per cent of doctors, much less than in so-called underdeveloped countries; three per cent of all lawyers; and one per cent of engineers. Professional schools habitually discourage women, and so do most of the teachers and career advisors they meet along the way.) Of the income elite, only five per cent of all people receiving $10,000 a year or more are women, and that includes the famous rich widows.

Of the prestige elite as taken from Who’s Who in America, they are six per cent. Of the business power elite (executives of corporations and the like), they are four per cent. And when it comes to elected officials, judges, and so forth, the percentage is almost nil.

Perhaps if women had more encouragement, more opportunity to gain power on their own, there would be less of the bitterness and hypocrisy that comes from using men for subversive ends. If society stopped telling girls that men can and should hand them their total identity on a silver platter, wives wouldn’t be so resentful when it didn’t happen. And ambitious women could relax, and look for pleasure instead of power in bed.

Men ought to encourage the idea. It might take a load off all of us.