I first meet Ron Galella when I break into his home.

The notorious paparazzo and his wife, Betty, live in a neoclassical megamansion in rural New Jersey. There’s a white marble fountain out front; columns frame the front door. It’s no surprise that an HBO scout once showed up, interested in renting the place as Tony Soprano’s home. (They passed because there was no pool in the backyard, only a rabbit cemetery.)

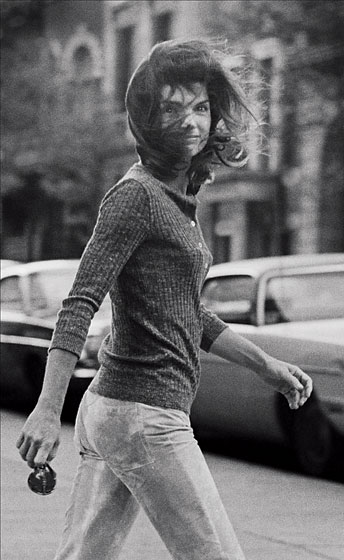

At the base of the stairs is a slab of concrete imprinted, Hollywood Walk of Fame style, with Galella’s handprints and his looping signature. I walk up and ring the doorbell several times, but it seems to be broken, so I yell, “Hello?” and finally turn the knob and open the door one hesitant crack. The first thing I see are rows of bright blue eyes. Liz Taylor. Barbra Streisand. Robert Redford. There are ten or so black-and-white pictures, their irises tinted, propped carefully on large easels—a gallery of iconic celebrity leading my gaze toward Galella’s Pop Art showplace of a living room, a stark white two-story atrium rising above a massive, S-shaped tomato-red love seat. Then I turn to the left and am startled by the image of Jackie Onassis. I can only see her eyes, which look terrified. A suited shoulder blocks her lower face.

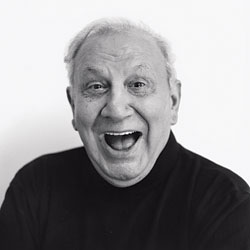

Suddenly, Galella appears, carrying a photo tripod that he uses as a crutch; he’s recently had knee surgery. “Hello, hello, come in!” he barks, friendly but gruff. Even at 77, Galella is a physically imposing man, with thick features, a boxer’s nose, and a staccato laugh. We walk past the Warhol-themed carpet; past the fireplace mantel featuring Galella’s ceramic sculpture of his hero, Cyrano de Bergerac; toward the dining-room table, which is covered, like so much of the house, in a shining mulch of books and prints. He pauses to hand me one of his favorite books: Disco Years, published in 2006.

“This book, the New York Times rated it best photo book of the year,” he says with pride. I flip through orgiastic images of Studio 54, catching glimpses of Ali MacGraw gyrating, her nipples visible through her tank top; a sleek Diane Von Furstenberg, legs scissored; Barbra Streisand slumped on a sofa with her 11-year-old son, Jason. Steve Rubell threw Galella out of Studio 54 not once but twice, he tells me. “We sued, and we won,” he says. “My pictures helped us win, because they showed him ordering the bodyguards. Heh heh heh!”

As we settle into the kitchen, with its massive white island, Galella’s wife, Betty, walks in, her arms wide in welcome. We’d spoken earlier, when I had to reschedule because of a child-care problem. “Oh, I totally understand,” she’d told me on the phone. “We have two children ourselves.” Really, I said, I didn’t realize she and Ron had any kids. “They’re both dead,” she replied. As I fumbled alarmed condolences, she merrily explained, in her warm southern lilt, that they were rabbits (Liz Smith and Walter Winchell, killed by raccoons only three weeks before).

As the three of us chat, I mention the photo I saw in the foyer, the one of Jackie O. pop-eyed in fright, her eyebrows to her hairline. The couple are completely appalled that I saw fear in her eyes. “What?” says Betty. “That is a beautiful shot!”

I make sure we’re talking about the same image: There’s a black man standing in front of Jackie, facing away—a bodyguard, maybe?

“That’s Muhammad Ali!” says Betty.

“He’s kissing her,” explains Galella.

Our culture has a wishful habit of turning every punk maniac who lives long enough into a wise old man, all the danger leached away by nostalgia: Norman Mailer, Iggy Pop, Roman Polanski. Ron Galella isn’t like that. He looks like an Italian grandpa, but his eyes are cagey. He’s prideful. He’s blunt. He’s a little bit frightening.

We sit in the kitchen, and he reminisces happily with me about the good old days, back when he turned his lens toward Hollywood. The son of Italian immigrants, Galella first got his hands on a camera when he was in the Air Force, during the Korean War; it was a Roloflex, and along with it he bought a book called How to Shoot Glamour. In art school under the G.I. Bill, he toyed with becoming a ceramicist (or a dance instructor: He went so far as to train with Arthur Murray). But Galella was eternally drawn toward the famous—he was curious, he says, to test the stars, to see if their glamour was real. The truth, he decided, was that anyone could become iconic; the camera itself was the true celebrity, a “magic medium” to which the famous owed their power. He even took acting classes at Pasadena Playhouse, not to become a star himself but to learn to act like one. “One of my instructors said I should go there to overcome shyness and fear, from dealing with these people. And it helped, it helped, it helped.”

His first big sell was a simple picture of a little girl, a bit of photojournalism—he’d tried to capture actress June Lockhart’s daughter at her preschool, but couldn’t get permission, so he shot a different child instead, earning $62. “But once I found celebrity journalism, I plied my know-how,” Galella says with satisfaction. “For a take of Elizabeth Taylor or the Lennon Sisters, you could get $1,000 from these magazines. Photoplay. Modern Screen. Silver Screen. And the National Enquirer, of course.” In those days, Hollywood photography was dominated by the glamour shot, that lacquered residue of American PR machinery. Galella embraced instead the piratical spirit of the Europeans, adding a certain entrepreneurial zeal all his own, blending high-art skills with a dedication that bordered on monomania.

By the time Betty met Ron, in 1978, he had already established himself as the dread paparazzo of his era—not the only one, but certainly the most famous, the most dogged. Richard Burton sent goons to steal his film; Brigitte Bardot had her boyfriend hose him down. Most notoriously, Jackie Onassis won a lawsuit against him in 1973, a court order for him to stay 25 feet away from her and her children. For years, he drove each day from the Bronx, where he had built a development lab in his father’s basement, to premieres, galleries, Park Avenue. “In 1967, I got Jackie at the Wildenstein Gallery. I followed her to her apartment, and once you know where they live, that’s where you have to be. They’re like a mouse coming out of a hole.”

Galella was 48, Betty 31. He’d never married because he was devoted entirely to his career, he tells me. He was also wary, emotionally insecure: His own parents’ marriage was combative, with the two retreating to live on separate floors. Galella’s father was “basic,” he says, an immigrant from the small Italian town of Potenza, who barely made a living building pianos and coffins. Ron favored his Americanized mother, who named him after the movie star Ronald Coleman.

Betty worked for a Sunday supplement, and she’d given him assignments by phone for two years. Ron proposed five minutes after they met in person. “I was a journalism major at the University of Kentucky, and I always had an interest in art and history,” she tells me. “But when I married him, I immersed myself in Hollywood. And I thought it was really vacuous. Which it is. I mean, c’mon—Lindsay, SamRo? But I got to go through his files, travel with him, and the lightbulb went off: This crazy guinea bastard has amassed a history! It’s sociological! He’s catalogued some of the most important moments in American history. Well, in celebrity—I’m not talking Roosevelt.”

Betty herself came from a family of Kentucky blue bloods; she is a member of the DAR. And in those days, Galella was regarded as a bug, a parasite: The word paparazzo is derived from an Italian word for mosquito. But from Galella’s perspective, he was always misunderstood. His art was a corrective to the artifice of the star system. It was a kind of forced Turing test of celebrity, determining whether the star is human. Only by seeing someone shocked and spontaneous can you tell if their charisma is genuine.

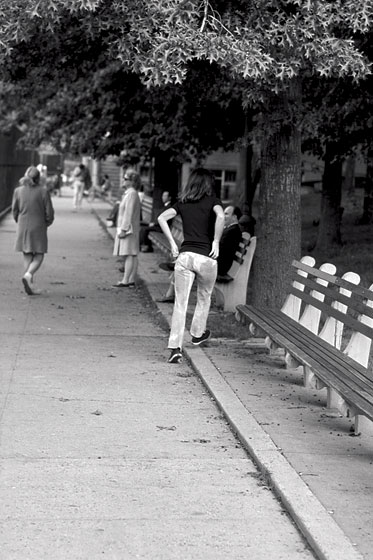

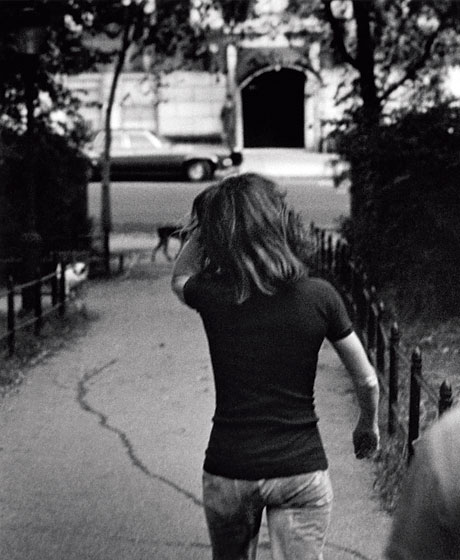

“I’m very quick, that was the technique: fast-shoot, fast-shoot! I don’t even look through the viewfinder. And you nail the picture like that, you get the surprise expression. Beauty that radiates from within.”

Galella talks to me about his favorite, most iconic photo, Windblown Jackie, an image of Jackie striding down the street, her hair blowing into her eyes as she turns her face, smiling, toward him—she didn’t realize Galella was there when she turned toward his cab’s honking horn. “I call it the Mona Lisa smile. It’s the beginning. The beginning of things are more interesting. Psychologically, it holds the future. Whereas the smile at the end is the big teeth. It’s good but not as good. Even in life.”

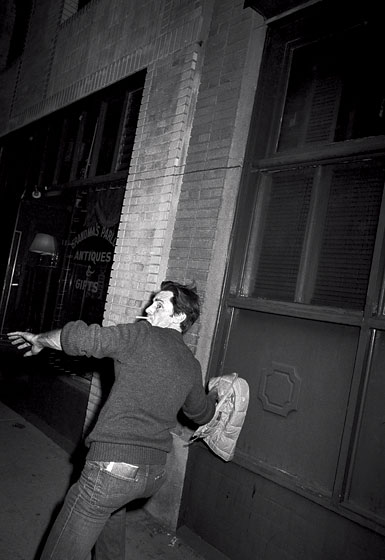

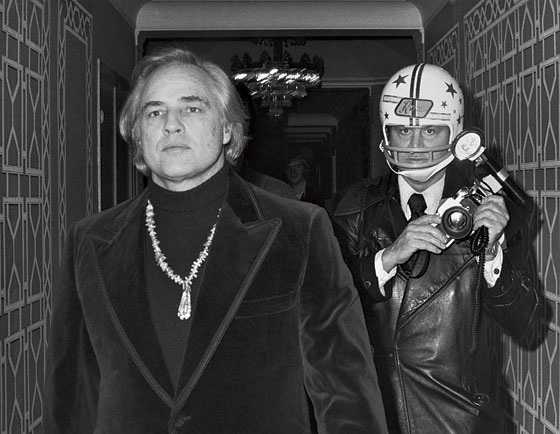

Galella is eager to distinguish himself from the more aggressive breed of paparazzo—both the old-style European photographers willing to break into a star’s bedroom and the new generation, assaulting stars to film their fear, zooming in on cellulite and bad plastic surgery. That wasn’t his style, he says. He’d hover, chatting up doormen, improvising with a combination of brass and discretion. Still, he found plenty of violence. In 1973, he followed Marlon Brando and Dick Cavett down to Chinatown, only to have Brando punch out five of his teeth (Brando had to go to the hospital with an infected hand). The two settled out of court, and later Galella returned to shoot the actor wearing a special football helmet, with ron printed on the front.

Ron and Betty began to spend entire days on stakeout together. This was long before cell phones and the mobs on the red carpet, and Galella prided himself on his cleverness in breaking into velvet-rope environments. He wore wigs, glasses, hats; he faked credentials. Once he cut a hole in a hedge to get a shot of Doris Day sunbathing. (In response, she built a wall, then moved far away.) He followed Jackie to a Chinese restaurant, then, after he was invited in by the owners, crouched behind a coatrack and—using only available light—captured an image of Jackie with I. M. Pei and Doris Duke. In the uncropped print, the celebrities are not alone: The waiters gaze into the camera, posing for Galella’s photo, while the stars they serve are oblivious.

Those were better days, he tells me. Today, the paparazzi care for nothing but money. “They’re unskilled. It’s terrible. I’m glad I do books. My books are my children. I can control the books.”

What he can’t control is the culture of exposure that seems much in his debt: not just the snarling videographers of TMZ but the larger universe of amateurs, the club kids upskirting their frenemies on Flickr, the reality stars marketing their own sex tapes. The stars today are “featherweights,” in his opinion. What Galella misses is that lost, thick, shiny veil of Hollywood glamour, the old studio stardom that was controlled and extreme and dishonest—and therefore, from his perspective, well worth tearing away.

Betty and he share the same opinion about the case of Britney Spears. They are disturbed by her, by the way she dated a paparazzo, by the deals she is rumored to cut with the very photographers who seem to be driving her mad. She’s a sick, sad child, says Betty. Perhaps because, unlike Elizabeth Taylor, she didn’t have the studio system to train her to be a star.

I ask Galella about the Miley Cyrus photos, the ones showing her half-naked. “Well, I think it’s dangerous. It’s dangerous in the fact that it promotes sex.”

“You can’t speak to that!” says Betty.

“I speak what I want.”

“Whatever.” She rolls her eyes.

Galella chuckles. “It promotes sexual promiscuity in the young. The sexual drive is enough to promote chaos in people’s lives. People mature too fast—by nature. These girls, they get knocked up, and usually the man is forced to get a job that he don’t like. He don’t have a career. He has to go to an A&P to develop—I didn’t have that, I developed a career! I think that’s what’s wrong with today. They get married too fast. They don’t love their job.” Heh heh heh.

“If everybody loved their job, it’d be a great world.”

These days, Galella feels vindicated as an artist, a pioneer in a “magic medium.” His prints are in MoMA, his books praised in the New York Times. He is a “bandit of images,” he says, quoting Fellini with the cheerful braggadocio he traces to his heritage. “Italians have a great culture, in art, in music. Michelangelo, Da Vinci. I say they’re my father! Because I could pick my father: I could study them, so they’re my father. Because my father’s not—you know.”

“Andy [Warhol] loved him,” says Charlie Scheips, worldwide director of photographs at the auction house Phillips de Pury. “He comes out of the tradition of Weegee. For me, they resonate as pure, old-fashioned, chemical photography—he will be remembered as a photographer of his era, as Jerome Zerbe was in the thirties.” But whereas Zerbe was part of elite café society, taking intimate portraits of his friends, Galella persisted as an outsider, documenting the stirrings of “a more casual age, when stars went out to discos, to nightclubs.”

Galella’s finest images still live most naturally on the printed page, says Scheips. The digital era has rendered his medium defunct. And while Galella’s mark may be everywhere (fashion magazines mimic his imagery, Scheips notes), “if people considered it high art, he’d have dealers all over the world. And he doesn’t.” (Galella points out that he does in fact have dealers in Amsterdam and Paris.) His market value could change, Scheips adds: “Who knows why one person hits it big-time? Jackie Onassis was not prettier than Lee Radziwill, but she was the one who was iconic.”

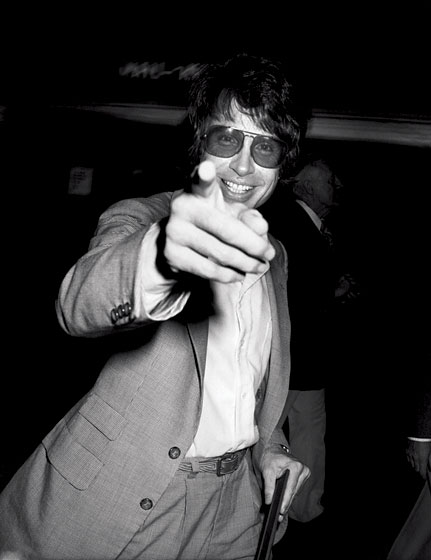

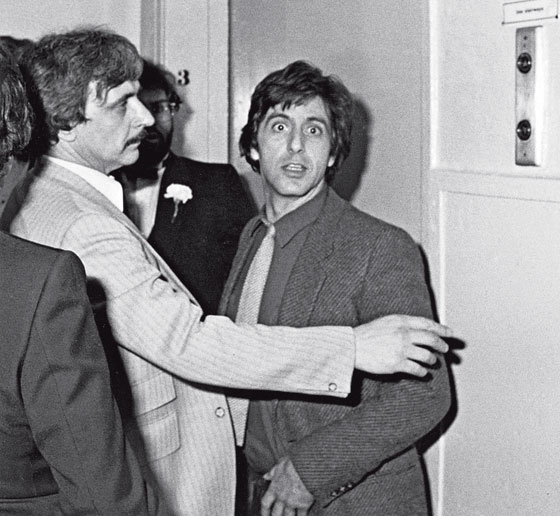

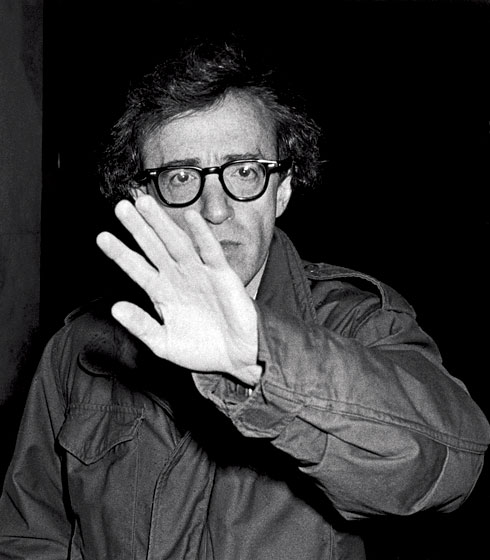

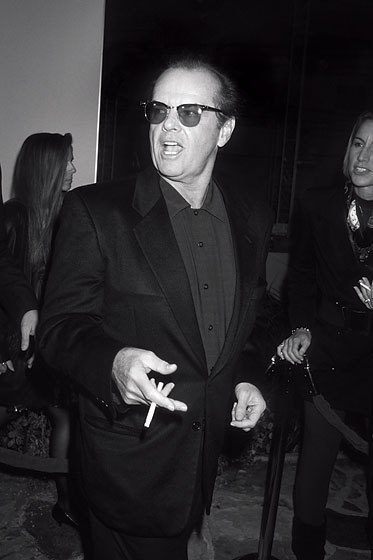

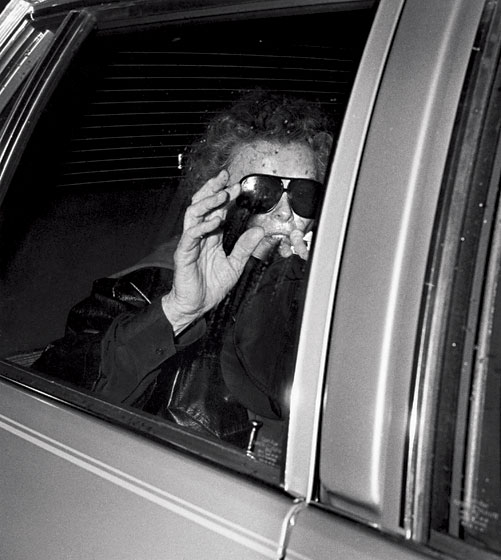

Galella’s latest book, No Pictures, due out November 1, is a series of denials: The stars hold up their hands, pushing away the camera. On the opposite page from each photo, in huge white print, is Galella’s recollection of what they said to him (“It’s Ron Galella. Run!” —Ryan O’Neal.).

A high-school Italian teacher, Mrs. Costanza, once told Galella that you are “somebody or nobody.” Deep down, everybody wants to be famous, he believes; to be famous is a “good thing,” to be photographed a compliment. So if stars say they are angry about being photographed, they are acting. If they ignore Galella as he shoots, they’re consenting. If they smile for one photo, and then disallow the next, they’re hypocrites. In fact, stardom itself is hypocrisy. “They pretend they don’t want it, but they really like it.”

Many of his best images are fueled by this tension between the thrilling visuals and the manner in which the photo was taken—the uncertain consent of his subject, the photographer’s motives, and then one’s own collusion as a viewer. There’s Woody Allen, wincing, palm up. A hooded Katharine Hepburn ducking into her limo. The long legs of Julia Roberts, her thigh in the foreground, as she huddles with Jason Patric, the two hiding their faces from the cameras after a long chase. Even Frank Sinatra looks atypically vulnerable, shouting, “You wop, you ask permission!”

The photographs are beautiful. But Galella’s most singular contribution to the culture is not aesthetic; it’s the way he has acted as an avatar for the public’s craving to at once elevate stars and force them to our level, a desire that seems to have grown only more ravenous, and more internally contradictory, in recent years. (Or to put it in Us Weekly’s terms, Stars: Are They Just Like Us?) Those who would judge the paparazzi are the same ones who gobble up their images, Galella points out. The best of these images offer their audience a glorious justice, a punishment and a reward for fame: the class war of the camera lens.

“Does anyone have that glamour today?” I ask.

“Some actresses have that old quality,” he says hesitantly. “Meryl Streep is a great actress, like Hepburn in a way. Nicole Kidman. They’re good actresses. But I don’t know if they’re as … glamorous.”

“Would you go to their homes?”

No, he says. “I’d rather do what’s- her-name—”

“Who would you doorstep?” Betty prompts him.

“Angelina Jolieeeee! Angelina Jolieeee!” he says, his eyes lighting up, catching that name and letting it furl out like a banner. “She’s got a sexy face. And the husband, he’s good-looking, too, Brad Pitt. Oh, Angelina Jolie and the family.”

And of course, Galella himself is now something of a celebrity, which he enjoys. (He loves being photographed, unlike Betty: The dedication to No Pictures calls her “so modest, unlike me.”) Some of the photos in the book rely on this peculiar dynamic: The star recognizes Galella, then performs the “no photos” stance as an homage. He even has a stalker, a woman who sent him intimate e-mails that Betty resented as invasions of their partnership.

Galella has no regrets for playing what he calls “the only game.” When he confronted Greta Garbo, back in 1969, she pulled out her umbrella and cried out, “Why do you bother me? I have done nothing wrong.” He felt bad, he said. He didn’t follow her the half a block to her home. But her photo is still in No Pictures.

Jackie, he tells me, was the biggest hypocrite of them all. Rich, haughty, a snob with (he claims) a secret scrapbook of press photos of herself in the closet. (He was told this by her maid, with whom he flirted in order to get access to Jackie’s whereabouts.)

And yet it’s clear that Galella is still besotted with his most famous subject fourteen years after her death. “Most of the time she would ignore me,” he tells me in a dreamy tone. “That was why she was my favorite subject. Because she allowed me to shoot my way.”

In his first book, Jacqueline, published in 1974, a year after losing the court case, he writes about how he misses shooting her. “They were thrilling times. I remember wandering through Central Park on fall afternoons and all of a sudden finding her, like a diamond in the grass.” Galella shot Jackie bicycling in Central Park; at Bobby Kennedy’s funeral; picnicking alone with her children in Peapack, New Jersey. Once, he got a precious image of her buying magazines at a newsstand, “paying for them with money, just like an ordinary American woman.” He even followed Jackie to the island of Mykonos, where he disguised himself as a Greek sailor to get bikini shots. Another photographer shot Jackie topless, but he tells me he wouldn’t have released that image: “I like to have taste that’s good.”

Galella knows he owes his own fame to Jackie and to the flashpoint that was their nonconsensual legal and artistic collaboration. When he chose as his subject the most famously private woman in the world, he sounded the death knell on that particular oxymoron. After Galella, celebrity evolved; it become democratized, diluted. Many stars choose to lean into the flash now, to be a canny collaborator rather than a subject to the surveillance. They market baby photos to reduce the value of spy-shots; they manipulate photographers to publicize their faux-personal dramas; they reveal so as not to be exposed. It is a development that Galella decries, but it’s also one he helped create.

When Betty leaves for a moment, Galella and I stand on his back porch, looking out at the elegant grounds, with its statues of the Four Seasons and the fountains he’s built by hand. We talk about the dead rabbits: He doesn’t think they’ll get any more, he says, because Betty “gets hurt when they die, she loves being a mother.” He points below us, to the elaborate playground they constructed for the rabbits, fully landscaped, with an air-conditioned area, a garden, and a sandbox. Upstairs in the house is the pink “rabbit room,” filled with Betty’s immense collection of rabbit memorabilia. HBO considered using it as Meadow’s room, and it does look like it’s for a little girl.

Galella tells me he’s glad they never had children of their own: It allowed the pair to devote their lives to the shared project of his art. As we reenter the house, I ask if there were any pictures he took that bothered him. He describes a photo of Jackie, taken at a restaurant.

“She was really angry, her Adam’s apple popping.” His face is dark, remembering. “I never released that picture. It was a negative thing that I don’t like to see. I like to see the positive—like Windblown Jackie. The cabdriver blew his horn, and she turned, and I got the picture!”

Two days later, I meet Galella in the city. He doesn’t like to come to Manhattan—it’s too long a trip, and he prefers to putter in New Jersey. But he’s been filming a documentary, revisiting his old haunts uptown, and now I’ve wangled us reservations at the Waverly Inn, that up-to-date variant on Studio 54.

The visit to the Waverly is a little strange. When we entered, Galella was wearing two enormous cameras dangling from his neck on thick black straps. No one asked him to check them, but I suspect we’re seated where we are, in the noisy Siberia of the front bar, because we looked so very wrong.

When I say hello to an old colleague, Galella yells a question to her over the din: “So, seen any celebrities?”

“Just Billy Joel’s wife,” she answers, glancing at us nervously.

While we wait for our salmon, we talk politics. Galella supports McCain, in part because of concerns about terrorism. I ask him where he was on 9/11. “I was in bed with Jackie,” he says, then laughs at his mistake: Heh heh heh! “I was in bed with Betty! Betty in a way is like Jackie, she has a soft voice. I’m louder. Although she got louder now, like me.”

When we leave the restaurant, Galella sets up shop on the corner of Bank and Jane and begins to snap away, gathering shots of the restaurant itself, with its clump of nobodies eating in the front garden. “There’s a market for these,” he says. No one stops him, no one even looks up.

Russell Simmons steps out, baseball cap askew. “Hey, Russell!” Galella shouts, and Simmons scurries by, looking annoyed.

We sit on a stoop to wait for the car. The day’s heat has broken, and gorgeous young people are strolling together in the cool air. We talk about tattoos, which he hates for the way they turn women into “walking billboards.” “That’s why I didn’t like what’s-her-name, the Cyrus girl, being so provocative. It makes other teen girls want to emulate her. It’s not good.”

I ask him if he thinks Annie Leibovitz’s taking those shots was wrong. “Hey, I would photograph her, don’t get me wrong,” he says, holding his hands up. “I would photograph her, and it would sell. Because I’m a voyeur, I shoot sexy stuff! You know, the sexiest is usually coming out of the limo—you get the legs.”

I ask him where he thinks voyeurism comes from.

“For me, it’s the mystery. What’s behind her clothes? What excites me is panty lines—and yet the women, they don’t want no panty lines. To me, it’s the sexiest thing: You say, Oh boy, look at that. I don’t think the little skimpy thing”—thongs—“I don’t think that’s too sexy, I don’t like that.”

I point out that his are old-fashioned fetishes. He’s living in an age where even the thong has become modest: Witness the parade of starlets flashing their panty-free undercarriages.

“The worst!” Galella moans. “I have a fixation for panties.”

Galella is a bit of a perv, I point out—“Not in a bad way, but you know what I mean.”

“I’m being honest with you! Most men are. I have a fixation toward—well, more than most men, really. I often wondered why I got it. I think it goes back to when I reached puberty, and out the window, I saw panties hanging. And I got excited. And I masturbated. And that’s how I got my release. That’s my analysis.”

While we sat in the Waverly, Galella had handed me a copy of Jacqueline. In it, he had put yellow stickies and underlined certain passages in red, most defending the free-speech ethics of photojournalists. These passages feel strangely dated, each element of his argument so altered—from the definition of privacy to the nature of fame—that it’s hard to reinhabit his lost world. And yet Galella’s fight against the phonies still has a perverse vigor, a way of making you root (against your will, perhaps) for voyeurism’s ability to get what it wants in the end. His books may be his children, but he has many other offspring, too: a darker cultural legacy he’d like to deny, though it’s got his eyes.

“Even though some snob journalists don’t want to admit that I am one of them, how many of them have had their work in Life, Time, Newsweek, and the New York Times?” he writes in Jacqueline. “It’s going to be a tough fight, but we’re going to win in the end.”

Selected photos on these pages from No Pictures, by Ron Galella, to be published November 1 by PowerHouse Books.