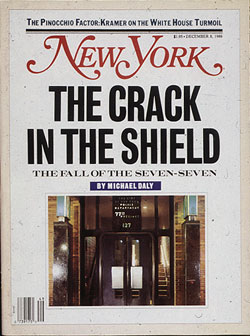

From the December 8, 1986 issue of New York Magazine.

Early on the morning he was to be arrested, police officer Brian O’Regan of the 77th Precinct arrived at his mother’s house with a cardboard box. He filled the box with a three-page will, a pair of spit-polished police shoes, an identification card from when he was a deputy sheriff in Florida, a thank-you letter from a citizen he had helped after a burglary, and a Christmas card from more than a decade ago that still held a $10 bill his grandmother had enclosed. He then neatly sealed the top with tape.

Shortly before dawn, Brian’s mother came out of her room in a flannel nightgown. She saw that her 41-year-old second son’s soft blue eyes were reddened and that his face was stubbled with a five-day beard. She asked if he wanted to talk.

“He said he didn’t have time,” Dorothy O’Regan remembers. “He said, ‘I can’t, I have to appear.’”

In the basement, Brian found his dead father’s razor. He shaved and told his mother he had to leave. She followed him as far as the back door of the small brick house. She called to him as he hurried into the dark and misty morning.

“I said, ‘Brian, you’re very upset. Drive very carefully,’ ” Dorothy remembers.

The mother closed the door against the chill. Brian drove his gray Subaru down the treelined lane where he had been raised. He rolled through the hushed suburban town of Valley Stream, and he came to the turn that would have taken him toward Brooklyn. He pulled the steering wheel the other way and headed east.

At 6:20 A.M., Brian checked into the Pines Motor Lodge on Route 109 in Lindenhurst. He registered as Danny Durke and paid $35. The desk clerk gave him the key to Room 1.

On a fluorescent-light fixture across from the bed, Brian propped a laminated Honor Legion plaque he had received for facing down a gunman armed with a .45-¬caliber automatic. He sat alone in this room 32 miles from Brooklyn as the twelve other indicted cops of the “Seven-Seven” surrendered on charges ranging from peddling crack to selling stolen guns. He opened a small notepad and wrote of watching a television report of his friends being arrested.

“Good morning, I missed my appointment,” Brian wrote.

Around noon, a Suffolk County police officer cruised the parking lot in search of a trio who had been robbing cash machines. Brian apparently panicked at the sight of the squad car, and he checked out. Desk clerk John Drake later discovered that he had left behind the Honor Legion plaque sitting on the light fixture.

“We figured he’d be back,” Drake says. “A cop would want to keep it. It would be important to a cop.”

By 12:30 P.M., Brian was again in the Subaru. He traveled farther east, and the housing developments gave way to bleak pine barrens. He kept driving into the gray afternoon and turned down Route 27 into Southampton.

At 3:30 P.M., Brian checked into the Southampton Motel. He registered as Daniel Grant and paid $37.65 for a night. He went into Room 2 with a green garbage bag containing his frayed uniform. He also had a pint of Seagram’s 7 Crown and a plastic bottle of 7 Up.

As he sipped a 7 and 7 from a paper cup, Brian again opened the notepad and began writing about his years as an officer in the 77th Precinct in Crown Heights-Bedford Stuyvesant. He had joined the Police Department in 1973 with the aim of being a good cop. He had soon discovered that this was not a simple ambition in a ghetto precinct that had become a dumping ground for the department’s misfits, malcontents, and rebels.

“I can’t swim in a cesspool, can you?” Brian now wrote.

Day after day, Brian had commuted to a combat zone where each year saw as many as 80 people murdered, an additional 100 raped, some 400 shot, and more than 3,000 robbed. He had made an arrest for drugs or gun possession again and again, only to see the “skel” back on the street the next day. The written law had seemed to leave him powerless. An unwritten law had kept him silent when he first saw an officer steal.

“I will not turn. No. Never. I won’t turn on another cop.”

By 1982, twin desires to be “one of the boys” and to get back somehow at the skels had led Brian to start shaking down drug dealers. He and several other cops were eventually seized by a frenzy of stealing. One of them would put a coded call over the radio, and they would assemble to hit narcotics spots with sledgehammers and ladders and sometimes axes borrowed from a firehouse. They had gleefully kicked in doors and swung on ropes through windows.

“I thought if you hooked up with them, I would be a big shot.”

At first, they had just taken cash. They had later begun selling narcotics and firearms. They had twice hit a location and then sold drugs to the customers who continued to arrive. Whatever pangs of guilt they had felt had apparently been numbed by a few hours of racing from shooting to robbery to rape to beating.

“No right. No wrong.”

In 1984, Brian had apparently begun to find his double life as a cop and criminal unbearable. He had begun to sink deeper and deeper into depression. He had eventually resolved to get out of the Police Department, and he had conspired to get a disability pension by having a fellow officer shoot him in the hand.

“I want to be normal. I want a life, I want a child.”

Finally, this same fellow officer and another cop had been caught shaking down a drug dealer. The two had agreed to cooperate with the special prosecutor, and Brian had been among those they had ensnared. The Brian Francis O’Regan who was known to his friends and family as good and kind and honest had been indicted on 82 counts in the biggest police scandal since the Knapp Commission investigation of the early seventies.

“I am guilty, but not guilty as you understand. I need help.”

At 5:40 A.M. on Friday, Brian woke in the motel. He went out twice for coffee and newspapers. He opened a second small notebook and wrote that he sided with police commissioner Ben Ward in a confrontation with the Patrolmen’s Benevolent Association over the department’s new plan to fight corruption by transferring each cop every five years. He also wrote that his stomach was queasy and that he had just inspected himself in the mirror.

“I look bad.”

At 9:20 A.M., Brian was still writing. He wrote that he had turned on the television and that the only clear channel was showing Donahue. He wrote that he loved his girlfriend, Cathy, and that he was afraid a SWAT team was going to burst through the door at any moment and that he did not own the proper clothes to wear to court. He noted that the motel’s noon checkout time was nearing.

“Only have about $4. What a choice. Death or jail. Got no place to go. Do you think God wants me? Does it hurt to die?”

Then Brian set down his pen. He left the two notebooks on the dresser and set his birth certificate and PBA membership card on the nightstand. He stretched out on the bed in a pair of denims and a light-blue sweatshirt bearing the legend 77TH PRECINCT—THE ALAMO—UNDER SIEGE.

With his right hand, Brian raised a .25 Titan automatic pistol he had most likely acquired while raiding a narcotics spot. He pressed the chrome muzzle to his right temple. He fired.

“The precinct is hell,” Brian had said some 30 hours before. “I know when I die I’m going to heaven.”

Brian O’Regan came to the New York Police Department from Valley Stream Central High School and the Marine Corps. His mother was the daughter of a Flushing truck farmer. His father was an oil-burner mechanic locally renowned for having built a Ford with two front ends and for riding a motorcycle down Merrick Road while standing on the seat. The father also had a practical streak that led him to approve of 28-year-old Brian’s career choice.

“My father used to say, ‘One thing about the Police Department, they never lay anybody off,’” the oldest son, Greg, remembers.

For his part, Brian seemed to come out of the academy with a dreamy vision of heroic comrades and daring deeds. He was assigned by chance to the 77th Precinct, and he arrived at the Utica Avenue stationhouse on October 29, 1973, raring to do battle with crime. He had only to be told what to do.

“Pride and glory,” Brian later said. “That’s what I liked.”

With a rookie’s blind enthusiasm, Brian was always ready to race to do a job or scramble up a fire escape or leap to an adjoining roof. He often returned to the suburbs with cuts and scrapes. His father suggested calling a family friend who was an inspector and arranging for a transfer to a less busy precinct.

“Brian said, ‘No, I’m new, I need some time there,’ ” Greg remembers.

On July 30, 1975, the fiscal crisis caused the city to lay off 2,864 cops. Brian was forced to turn in his gun and shield and search for another job. He heard that the Broward County sheriff was hiring, and he went down to Fort Lauderdale to sign on as a deputy.

When his nieces visited Brian in Florida, they found him driving a police cruiser that gleamed right down to the steam-cleaned engine. He wore a fitted white shirt and a shiny brass badge and a Smokey the Bear hat. He had begun collecting thank-you letters from citizens he had assisted, and supervisors spoke of promoting him to detective.

“He always had a smile on his face,” says his niece Kathleen. “He’d say, ‘How do I look? How do I look in my uniform?’ ”

In 1980, Brian’s father died of a heart attack. Brian flew north and attended the wake at the Moore Funeral Home in Valley Stream. The New York Police Department was hiring again, and he announced that he was moving home. The family urged him to stay in Broward County.

“I said, ‘You should go back to Florida where you’re happy,’ ” remembers his sister-in-law, Carole. “He said, ‘No, I have to take care of my mother.’ ”

On January 13, 1981, Brian returned to the 77th Precinct stationhouse, on Utica Avenue. He climbed into a grimy squad car with coffee stains on the seats, and he drove onto the Atlantic Avenue viaduct. As far as he could see were abandoned buildings and housing projects.

“I said to myself, ‘What the hell am I doing here?’ ” Brian later remembered.

As he began patrolling these battered streets, Brian learned that black Brooklyn was the department’s dumping ground and that his fellow officers included a large number of drunks, shirkers, boss fighters, rule benders, rebels, and crooks who were not quite crooked enough to fire. An officer would misbehave in some choice command and Brian would see another new face in the Seven-¬Seven.

“You would ask the guys, ‘What did you do wrong to get here?’ ” Brian later said. “They might not tell you, but you knew something.”

Among the brass, the Seven-Seven had acquired a reputation as an “unmanageable precinct.” Brian sensed that most of the supervisors there cared little about the neighborhood and not much more about what the officers did. Many seemed to him concerned only that a cop issue summonses and keep his overtime down. Many seemed to have one overriding desire.

“You look at them and you know it’s ‘I got to get out of here,’ ” Brian later said. “You basically could do what you felt like doing.”

On one of his first radio runs, Brian pulled up to a dress shop on Nostrand Avenue that had been burglarized. The plate-glass front window had been smashed, and Brian followed several other officers inside. He watched one of the cops punch open the cash register and grab a stack of bills.

“I could not believe what I saw,” Brian later remembered. “He said, ‘What do you want?’ and I said, ‘I don’t do that. I do not do that. I don’t want anything.’ ”

During another tour, Brian responded with lights and siren to a radio report of three men with guns. Other cars screamed up to the scene, and several cops crashed through the Plexiglas front of a smoke shop in apparent pursuit of the perpetrators.

“Somebody said, ‘Did you drop a dime?’” Brian later remembered. “I didn’t understand. I just looked at him.”

Afterward, Brian learned that cops sometimes telephoned a bogus crime report into 911 and used the resulting radio run as a cover for pillaging a smoke shop or a numbers spot. He already knew that even honest cops usually maintained a wall of silence between themselves and an anti-corruption apparatus that included the precinct Integrity Officer, the Internal Affairs Division, the Field Internal Affairs Unit, the district attorney, and the special prosecutor.

“The Blue Wall,” Brian later said.

One day, police officer Francis Shepperd went into a numbers spot in uniform and staged an armed robbery. The crime was so brazen that another cop contacted IAD out of fear that the department was staging some sort of integrity test. Shepperd was dismissed and the other cop was ostracized. His locker was turned upside down and branded with the word “rat.”

Brian kept his silence and raced to as many as twenty jobs in an eight-hour tour. The precinct’s homicides in 1981 included the July 4 shooting of two men and a woman on St. Johns Place. A crowd of citizens ignored the bodies and gathered around a new Mustang that had a bullet hole in the right front fender.

“Poor car,” a man was heard to say.

On an evening tour, Brian shone his flashlight from an upper-floor tenement window and saw a tiny dark form down below he could not immediately recognize. He then realized that the woman in the apartment had thrown her newborn child down the air shaft. Brian later said, “I stood there and stared at it and I kept thinking, It’s so little, it’s so little.”

At the stationhouse, police officer Peter Heron warned Brian that the routine of mayhem and misery could change a person. Heron was later fired for shooting heroin. Brian went on patrolling the streets of the Seven-Seven. He delivered eight babies. He made nine gun arrests in a single month.

On Lincoln Place, Brian grabbed a dope dealer named Mitch twice for guns and once for drugs. None of the arrests seemed to interrupt Mitch’s business for more than a few days, and the man flashed a big smile each time Brian’s squad car pulled onto the block.

“You put somebody in jail and the next day he’s out waving to you,” Brian later said. “So what did you accomplish?”

Other officers experienced similar frustrations and sometimes administered summary punishment to dope dealers by flushing the drugs down a toilet, tossing the money to neighborhood kids, or otherwise “busting chops.” These cops included police officer Henry “Hank” Winter, a fellow Valley Stream Central High School alumnus who lived across the street from Brian’s uncle and who was known to have once left a pusher naked on Jones Beach in December. He now became something of a precinct legend by burning a dope dealer’s bankroll on a table in the roll-call room.

“Henry Winter has personality,” Brian later said.

At some point, Winter began slipping confiscated cash into his pocket. He kicked in doors and rappelled through windows to rob pushers of their “nut.” He then went back to the stationhouse joking and laughing. Brian had an adjoining locker and sometimes saw Winter count a wad of cash.

“He’d say, ‘Not a bad night,’ ” Brian later said.

In March 1983, another cop was suspended for suspicion of robbing a smoke shop on Dean Street. Brian’s younger brother, Kevin, heard of the incident and called to ask what had happened. Kevin remembers, “Brian said, ‘I don’t know, but sometimes you just work too long in a precinct and things can happen.’ ”

Around this time, police officer William Gallagher asked Brian to be his regular partner on the steady midnight shift. Gallagher was the precinct union delegate. He called himself a “hero cop.”

“He was cement,” Brian later said. “He wanted me because I’m easy, because I’m a follower.”

As they began riding together, Gallagher sometimes did not deign to speak even when Brian asked him a direct question. Brian accepted the insult and seemed to become devoted to his new partner. A friend named Patricia Cuti says, “It made him feel very macho just being in a car with Gallagher.”

Early one morning, Gallagher pulled the squad car over and led Brian into a smoke shop. Brian later remembered, “He said, ‘I want to do this place.’ I didn’t know what he meant.”

Behind the counter, Gallagher found a bin filled with cash. Brian later said that Gallagher grabbed the money and returned to the squad car. There, Gallagher held out $150. Brian hesitated. Gallagher kept his hand out. Brian took the money.

“I felt like I was one of the boys,” Brian later said.

At roll call, Brian began standing off to the side with Gallagher and the other “Raiders” of the late tour. He then joined the nightly prowl for drug locations. Brian proved to have a real talent for spotting lookouts and other signs that meant a dope dealer was operating nearby.

“I would have done great in narcotics,” Brian later said.

When the cops wanted help hitting a spot, they got on the radio and said, “Buddy Bob, meet at 234.” The code phrase summoned all interested officers to gather at St. Johns Recreation Park, near Engine Company 234’s firehouse. They then set out together to make a raid.

Since many of the spots were fortified, one cop took to borrowing sledgehammers, axes, ladders, and ropes from Engine Company 234. Gallagher and Brian began keeping a sledgehammer in the trunk of the squad car. They would splinter the door with a great blow of the hammer and rush screaming into the room. They would see fear and anger in the face of a once smug dope peddler.

“It was glory,” Brian later said. “It was not money. It was you finally getting back at all the slaps you took. It was getting back at the skels, back at people you couldn’t hit.”

One night, Gallagher and Brian went with Winter to a construction site. They then rode through the precinct with a stolen ladder atop the squad car. They stopped in front of an apartment building on Eastern Parkway and propped the ladder on the car’s roof. Gallagher scrambled up and began kicking in the windows of a narcotics spot.

“I wanted adventure, some kind of excitement,” Brian later said.

During one tour, several officers of the Seven-Seven came upon a van filled with cigarettes. They correctly guessed that this was bait set out by the Internal Affairs Division. They then had great fun banging the sides of a second van where the IAD men were hiding.

“They must think we’re stupid,” Gallagher was later heard to say.

Even as rumors began circulating that a number of officers were about to be arrested for shakedowns, Brian and the others continued hitting narcotics spots. They gave each other nicknames, and Brian became “Space Man.” Gallagher was “Junior,” and his swaggering presence seemed to keep Brian fearless. Brian later said, “He was infallible. He could get out of anything.”

After work, the cops became family men and good citizens. Brian did not smoke and seldom drank, and his idea of a good time was going to a flea market. He kept to the speed limit when he drove, and he always came to a complete halt at a stop sign.

“We never did anything out of uniform,” Brian later said.

In late 1983, Brian met a rookie policewoman at the stationhouse. She later remembered, “He said, ‘Get out of here as soon as you can. Just leave this place. Get out before it changes you.’ ” Around that time, Gallagher became friendly with a West Indian dope dealer named Roy. Brian later said that the cops began selling Roy stolen drugs. They also started selling him stolen guns.

“Sometimes, I used to get a feeling, a deep, deep feeling of guilt,” Brian later said. “But then it would go away. I would go back on patrol and it would go away.”

As the days passed, Brian began to take less and less care with his appearance. He let himself get out of shape, and he began to get a paunch. He turned out in a uniform that was stained and frayed.

“I had no pride,” Brian later said. “Nobody becomes a cop to steal.”

At a family gathering, relatives noticed that Brian seemed troubled and agitated. He had begun to suffer a sort of numbness, and he later said, “Anything could happen, and I just wouldn’t care…. I said, ‘I’m dead and I don’t know it.’”

With the hope that there might be some physical explanation for his problem, Brian went to a doctor on Ocean Parkway. The doctor found no malady and urged him to seek psychiatric care. Brian mentioned this at the stationhouse, and officers began twirling an index finger by their heads when he appeared.

“If you tell somebody you have psychological problems, they think you’re crazy,” Brian later said.

The gloom deepened, and Brian spoke to Henry Winter about somehow leaving the Police Department with a disability pension. Brian later remembered, “He said, ‘We’ll get you shot,’ and I said, ‘That sounds good.’ ”

As they discussed the matter, Winter offered to help Brian stage a fake gun battle. Brian suggested that Winter shoot him in the leg, and he later remembered, “He said, ‘No, too many arteries.’ He said, ‘The hand’s better.’ ”

One evening, the two cops went into an abandoned building on Porter Avenue, and Winter gave Brian a .22-caliber pistol. Brian took the weapon with one hand and held out the other. He aimed and curled his finger on the trigger and then lost his nerve at the last instant. He returned the gun to Winter and asked him to do the job. Winter refused, and they handed the gun back and forth, saying, “You do it.” “No, you do it.” “I’m not doing it, you do it.”

As they continued to steal, Winter appeared to share none of Brian’s anguish. He was forever laughing and joking. On a dare, he did a striptease on top of the front desk.

In early 1985, Winter and his partner, Tony Magno, were sharing $50 a week in protection money from a pusher who also ran a dice game. A pair of anti-crime cops demanded a cut and raided the game when Winter and Magno refused. The pusher resolved the matter by paying the four cops a total of $800 a week.

That October, Gallagher got word that a pusher had complained to IAD of shakedowns and that detectives were putting together a case against Winter and Magno. Gallagher passed on a warning, and Winter and Magno grew cautious. The others went right on raiding spots.

“You just couldn’t stop from happening what was happening,” Brian later said.

On February 17, 1986, an unmarked car pulled Winter’s car over on the Belt Parkway as he returned from a fishing trip. Winter was whisked in handcuffs to the IAD building on Poplar Street. There, he and Magno were sat down before a television set and a VCR.

A lawyer from the Special Prosecutor’s Office played a videotape showing Winter and Magno taking protection money from a drug dealer outside a St. Johns Place building. The lawyer then said that they had two alternatives. They could go to jail or they could cooperate.

“You just show them what you have,” says Special Prosecutor Charles J. Hynes. “It’s very dispassionate. You just say, ‘Here’s your choice.’ ”

As he made his decision, Winter no doubt considered Dennis Caufield, his brother-in-law and a former cop. Caufield had worn a wire seven years before, in an investigation that had led to the arrest of four anti-crime officers. He was subsequently rewarded with a promotion to detective and a transfer to the 17th Precinct. Winter and Magno now settled for being what Hynes calls “unarrested.”

“To catch a thief, you got to turn a thief,” Hynes says.

In May, Winter and Magno arrived at the stationhouse wearing micro-recorders. They joined in raids on narcotics spots and recorded cops talking about other scores. They put out the word that they were willing to “fence” stolen property, and cops brought them drugs and guns.

At the end of each tour, Winter and Magno met secretly with IAD and handed over their 90-minute micro-cassettes. One cop was recorded boasting of pilfering $8,000 in cash and $3,900 in food stamps from a burglarized supermarket on Franklin Avenue. Another chatted about stealing cars while on duty. Another gossiped about a cop who had killed a man and woman for $1,500.

On June 17, Gallagher put a “Buddy Bob, meet at 234” call on the radio. Winter met Gallagher and Brian at the park across from the firehouse, and they all went off to hit a spot at 143 Albany Avenue. They first searched a second-floor apartment, without success.

When Brian shone his flashlight down an air shaft, he spotted a paper bag. Winter lowered himself down and discovered that the bag contained crack vials. Brian then found a .357 Magnum and a potato-chip sack filled with more of the drug.

Back in the park, Brian helped count the total score and discovered they had more than a half-ounce. Brian “fenced” the .357 Magnum through Winter for $200. The drugs were sold to the West Indian drug peddler, Roy. Winter turned over his $1,000 share to IAD.

On June 18, Brian and Gallagher spotted a couple buying drugs in the doorway of an apartment at 261 Buffalo Avenue. Winter helped hit the spot, and he discovered a trapdoor in a third-floor apartment. He pulled out a bag containing marijuana and $107 in cash.

Brian pocketed the money, and Winter offered to sell the marijuana. Winter then took the pot to IAD, and an investigator gave him $400. Three days later, Winter passed the bills to Gallagher.

That same day, Brian told Winter that he had spotted a new narcotics spot, on Classon Avenue. He telephoned Winter the next day and said that he and Gallagher had raided the place and come away with $70 and 58 vials of crack. He asked Winter to handle the sale.

On July 1, Brian and Gallagher got into a car with Winter. Brian placed a package containing crack in the glove compartment. Gallagher spoke about an upcoming sergeant’s test and other PBA business and then handed Winter a slip of paper with the notations “52/10” and “19/5.” The figures apparently corresponded to the number of $10 and $5 vials.

“Fifty-two and nineteen,” Brian was recorded as saying.

On July 4, Winter met with Gallagher and said he had sold the drugs. Winter then gave $400 to Gallagher, who returned $100 as an apparent commission. Winter spoke to Brian later that day and told him of his transaction.

“You work, you stick your neck out, you get paid,” Brian was recorded as saying.

Six days later, Winter joined Brian and Gallagher in raiding a building at 1226 Lincoln Place. Gallagher entered one apartment by yanking the fire-escape window from the sash. The cops had been tipped that a “nut” was hidden there, and they ripped out radiators and tore up floorboards.

On July 11, Winter and police officer Robert Rathbun went on patrol in an unmarked car. Rathbun spoke to Winter of his family and said that he was taking his children on a camping trip. Rathbun was then recorded as saying that he was hoping to pick up “sneaker money” before he left.

A few minutes later, Rathbun and Winter hit a spot at 1260 Pacific Street. They had just found a stash of marijuana when a knock came at the door. They peered through a slot in the door and saw that a line of customers was forming.

As the line grew, Rathbun allegedly joined Winter in exchanging nickel bags of pot for money through the slot. They then drove to Kings Plaza shopping center. Rathbun went back to the stationhouse with a new pair of Reeboks.

Afterward, Gallagher and Brian went to the spot and allegedly tried the same stunt. The marked radio car parked outside the building apparently kept away most of the customers, and the two left with only a few dollars.

On July 30, Brian joined Gallagher and Winter in a foray to the Soul Food shop on Franklin Avenue. Brian rummaged through a hallway trash bin and found a .25-caliber automatic pistol that he later “fenced” through Winter for $100. The other cops stuffed the spot’s drugs and cash in a bag.

Apparently, everybody thought someone else had the bag, and the cops managed to leave behind the booty when they departed. Winter’s micro-recorder picked up one of the officers saying, “What are we, a bunch of f–ing Keystone Cops?”

At one point, Brian sat with Winter in a car and spoke once again of somehow getting a disability pension. Brian later remembered, “I said, ‘I wish I could care about something. I wish I could give a f– if somebody jumps out a window.’”

On August 4, Brian and Gallagher received cash from Magno. They chatted with him about guns and drugs. They spoke of a dope dealer named Herbie who was paying $1,000 a week for protection.

Later, Magno met secretly with an IAD detective at Ocean Parkway and Avenue C. Magno gave the detective a micro-cassette. The detective handed Magno a new tape and fresh batteries for the recorder. The detective then wrote a report headed “77 Pct. payoffs tape retrieval and debriefing of P.O. Magno.” The document reads in part:

Gallagher received from P.O. Magno $635 u.s.c. for himself and his partner in reference to worksheet #486 for drugs. P.O. Gallagher agreed to sell guns to P.O. Magno’s alleged fence. P.O. Gallagher stated that the drug dealer he and his partner P.O. O’Regan are protecting is looking to expand his operation to either 173 or 193 Buffalo Ave., exact location and time unknown. Drug dealer’s name is Herbie, 1369 St. John’s Place. Gallagher told Magno that anti-crime hit Herbie’s place…. Gallagher felt that Winter should have steered Anti-Crime away from Herbie’s.

P.O. Magno engaged in conversation with P.O. O’Regan. O’Regan told him that a rival of Herbie was hit in order to be in good standing with Herbie. O’Regan also mentioned that himself and his partner P.O. Gallagher received #2,010 u.s.c. from Herbie as pay-¬off money. O’Regan further stated that now Winter and Magno can get rid of drugs at a more profitable rate, Roy’s services will no longer be needed.

At the Special Prosecutor’s Office, the report went into a file of more than 900 such documents. Photos of Brian and Gallagher and Rathbun were pinned on a wall of the “Target Room” under the heading “Criminal.” These were joined by pictures of close to 25 others. Still more were under the headings “Administrative” and “Possible,” and the overall total rose to almost 50 of the precinct’s 200-odd cops.

Rumors were by then circulating that Winter and Magno were wired. Rathbun patted Winter down, without discovering the micro-recorder. Brian arrived for work and saw that somebody had scrawled the word “rat” on Winter’s locker.

“I ¬didn’t believe it,” Brian later said. “Not Hank.”

At the front desk, a fellow cop called Gallagher aside and gave him a friendly word of warning. Gallagher shrugged and was heard to say, “Anybody who steals out there is crazy.”

On September 4, police officer Crystal Spivey allegedly accepted $500 to help Winter escort a narcotics shipment. They drove to the post office at Third Avenue and 29th Street in Sunset Park, and an undercover cop posing as a dope dealer appeared with a kilo of cocaine. Winter and Spivey then drove to the Canarsie Pier. IAD detectives in a nearby van videotaped Spivey handing the shipment to a second “dealer.”

By then, Brian had begun speaking of marrying a young woman named Cathy. He looked at a modest house in Rockville Centre and started negotiating with the owner. He later said, “All I want is a house. Just a house and a wife and a child.”

Still, Brian would leave Cathy’s apartment each work night and find himself in another raid on a narcotics spot. He and Gallagher allegedly agreed to assist the pusher Herbie by eliminating a competing location at 233 Utica Avenue. They hit the place again and again.

On the night of September 17, the dealer named Roy approached Winter in the precinct and said that the proprietors of the Utica Avenue location had decided to shoot the next cop who came through the door. Winter immediately relayed the information to IAD. The same evening, Spivey went up to Winter at the stationhouse. She asked to speak to him in private, and they went outside to his car. She announced she had been tipped by a sergeant from another precinct that he was wearing a wire. She frisked him and failed to find the recorder taped to his crotch. Her suspicions were apparently allayed.

“You wouldn’t dog me like this,” Spivey was recorded saying.

In the morning, the Special Prosecutor’s Office instructed Winter to take Spivey on a second narcotics run. She is alleged to have immediately agreed, and she was recorded as saying, “I want to buy a condo.”

On Winthrop Avenue, detectives stopped the car and took Winter and Spivey to the IAD building. The Special Prosecutor’s Office offered Spivey a reduced sentence if she would help determine how word of the investigation had leaked. She agreed and headed out with a micro-recorder of her own.

At the same time, Hynes said that the leak left Winter in too much jeopardy to continue. Hynes canceled plans to send Winter and his micro-recorder to a beach party with a new group of suspected cops.

That night, Brian reported for duty and heard that an IAD investigator had returned Winter’s portable radio to the stationhouse. Brian immediately checked the stationhouse log and saw a notation by the names Winter and Magno.

“It said, ‘Transferred to IAD,’” Brian later remembered.

In the back, Brian checked Winter’s locker. The IAD investigators had cut off the lock. They had carried away everything except for a single brass collar device bearing the numerals “77.”

On Saturday, September 20, Brian drove to Winter’s white frame house in Valley Stream. He did not see Winter’s car, and he went to a tag sale. He called Cathy from a pay phone to say he had found an eyelet-edged sheet set. She told him $10 was a good price, and he hurried back, only to find the set had been sold.

On a second swing by the white frame house, Brian saw a woman he recognized from pictures as Winter’s wife. He later recalled, “She looked like she had been through a war. I said, ‘I’m Brian.’ She said, ‘He’s not here and I gotta go.’ ”

As Brian began to pull away, he saw Winter drive up with some relatives. Brian later remembered, “I said, ‘Hank, how are you doing?’ He said, ‘Hey, buddy boy.’ He has a big smile on his face and he says, ‘I’ll see you later.’”

Brian returned to his apartment in Rockaway. The owner of the house in Rockville Centre called to accept Brian’s latest offer. Gallagher also telephoned and warned Brian to stay away from Winter. Brian went to Gallagher’s house in Marine Park and found his partner sitting in the dining room.

“I said, ‘What’s the problem? What’s going on?’” Brian later recalled. “He said, ‘I told my wife everything.’ I said, ‘Everything?’ He said, ‘Yeah. We could be in big trouble.’”

That Monday, Crystal Spivey appeared at the Special Prosecutor’s Office and said she would continue to wear a wire only if Hynes guaranteed her probation. Hynes said she would have to do at least a one- to three-year term. She balked, and Hynes canceled the deal.

On Tuesday morning, Chief John Guido of IAD decided he could not risk having a noncooperating Spivey tip off other officers. He reached for a folder on his desk that contained the names of thirteen targeted cops.

“Take them! Take them!” Guido was reported to have said.

Rathbun was processing a prisoner at Central Booking when he called his wife and learned that he had been suspended. Another cop was waiting with his fiancée to be seated at a restaurant when the news came over the television in the bar. Brian first understood that something had happened when his friend Patricia Cuti telephoned.

“Pat said, ‘What’s the matter, what’s going on at the precinct?’ ” Brian later recalled. “She said, ‘Turn to Channel 4.’”

When he flicked on the television, Brian heard himself named as one of the thirteen cops who had been suspended. The others included a sergeant who was often the sole supervisor of Brian’s shift in the field. Brian called the sergeant to break the news.

“I had to tell him five times. He wouldn’t believe it,” Brian later remembered.

Later that day, Brian drove to the stationhouse and went through a side door to avoid the crowd of reporters out front. An IAD investigator instructed him to surrender his guns, identification card, and gas card. The investigator followed him to his locker.

“I guess they’re afraid you’re going to blow your brains out,” Brian later said.

As he emptied his locker, Brian paused to write the single word “suspended” in his memo book. He then turned over what was required to the investigator and headed out past the front desk.

“I can remember who was standing where and what they were wearing,” Brian later said. “I remember everything in great detail, but after I left the precinct I don’t know where I went. I can’t figure out where I went.”

The next day, Brian and some of the other suspended cops went to the PBA to seek legal assistance. Gallagher cried six times, and Brian later remembered, “I said, ‘Holy shit, I can’t believe this here. He was always cement.’”

Afterward, Brian sat with Rathbun in a car. Rathbun was also crying, and Brian later recalled, “I said, ‘Maybe it’s not so bad.’ He took out his wallet and showed me a picture of his son and said, ‘See this? How could you ever tell him?’”

When he reached Cathy’s house, in Brooklyn, Brian still had not broken down. She was red-eyed when she met him at the door, and he later remembered, “I said, ‘Are you crying?’ She said, ‘No.’ I went upstairs and I burst out crying.”

Back at his own apartment in Rockaway, Brian stopped to speak with his landlord. His brother Greg remembers, “Brian said, ‘That was me in the paper,’ and he said, ‘I know it was, Brian.’ Brian said, ‘If you want, I’ll move,’ and he said, ‘Absolutely not.’”

Over the days that followed, Brian would visit his mother’s house only when the night hid him from the eyes of the neighbors. He was reluctant to attend a birthday party for his brother Greg, and his sister-in-law, Carole, remembers, “His first concern was what would the kids think of him.”

During the party, Brian and Carole retired alone to a corner. Their conversation touched on the suicide of Donald Manes. Carole said that the man should have ridden out his troubles, just as Brian should ride out his own difficulties.

“I said, ‘People forget fast,’” Carole remembers. “I said, ‘Look at Richard Nixon.’”

Through the family, Brian contacted a lawyer. Brian asked about the possibility of pleading insanity resulting from a sort of battle fatigue. Brian later said, “They call it the war on crime. The war on drugs.”

At one point, Brian sought advice from a veteran of the Seven-Seven who had once been arrested for armed robbery. Brian also described his predicament to a psychic. Cuti remembers, “The psychic told Brian that he probably wouldn’t continue being a cop.”

On another day, Brian walked into a church in Rockaway and confessed his sins in the Seven-Seven to a priest. Brian later remembered, “I thought he was going to fall over and take a heart attack, but he didn’t even bat an eye. He said, ‘I’ve heard worse. Just get a good lawyer and be prepared for what might happen.’”

From the church, Brian headed home and telephoned Winter. The answering machine was on and eleven more of Brian’s words went on tape. Brian later remembered, “I felt so clean and pure. I said, ‘Hank, this is Brian O’Regan. I don’t hold anything against you.’”

Around that time, Winter began testifying before a grand jury. He and Magno helped the Special Prosecutor’s Office secure indictments against thirteen cops and prepare cases on about a dozen more. Brian was charged with some 80 crimes.

“It’s funny how you can be good for your whole life, for so long, and then…” Brian later said.

On November 4, Brian called Cuti and said that he had been notified to surrender the following Thursday. He said he planned to show up in dark glasses, a hooded sweatshirt, and a hat.

“He was scared to death,” Cuti says.

The following day, Brian stopped by Cathy’s house and gave her white carnations for her twenty-fifth birthday. He also drove to a notary public in Queens with a will he had typed himself. He later made an appointment with Mike McAlary, the New York Newsday reporter who had broken much of the story behind the investigation.

At 10 P.M., Brian met with McAlary and this writer at the Ram’s Horn diner in Rockaway. Brian spoke for four hours and then went home. Cathy called him, and he told her that he planned to surrender with the others and that he might shave for the arraignment. He then drove through the rainy pre-dawn darkness to his mother’s house.

Five hours later, all the indicted cops except Brian arrived at the IAD building. They came out an hour later in handcuffs and rode to Central Booking. They had all taken prisoners there in the past, and they did not have to be told the procedure for photographing and fingerprinting.

At 11 A.M., a clerk on the fifth floor of Brooklyn Supreme Court announced that the first item on the calendar was Indictment SPOK 224. Gallagher shuffled in wearing a black jacket. His shoulders were slumped. His head was bowed.

“Step up, please, Mr. Gallagher,” the clerk said.

After entering a plea of not guilty, Gallagher’s lawyer noted that his client had received 35 medals and commendations during his seventeen years as a cop. Hynes responded that Gallagher was accused of 87 felonies and misdemeanors. The charges included the sale of crack and of loaded handguns.

His bail set at $50,000, Gallagher shuffled back out. Rathbun then appeared and pleaded not guilty to 37 counts that included selling drugs. He was followed by Spivey and nine other cops who pleaded not guilty to charges ranging from the sale of cocaine to burglary to the theft of two garbage cans from the stationhouse. Spivey’s face was blank as she listened to a prosecutor say she was charged with an A-I felony. The prosecutor added that this carries a maximum penalty of life in prison.

By that time, the police had put out an APB for Brian’s gray Subaru. Winter and Magno are said to have kept searching for him for the next two days. Brian’s brother Greg began to fear the worst when the mail brought a brown envelope containing a one-page typewritten letter.

“I’ve always considered myself to be an honest, upstanding person.”

“I was firmly convinced that nobody cared in the ghetto, from the people who lived there to the police and the city.”

“I’m sorry it had to happen this way, but it did.”

“Try your best to take care of mom.”

On the afternoon of Friday, November 7, a neighbor told Greg that the radio was reporting that Brian had been found dead in a Southampton motel. Greg and Kevin went to the Suffolk County medical examiner’s office and identified the body. Two other relatives then took the Subaru to Greg’s house.

That Sunday night, Brian was laid out in the room at the Moore Funeral Parlor where his father’s wake had been, six years before. The family gathered for a private viewing, and afterward Greg went to his mother’s house. The phone rang, and Greg spoke for a moment to Gallagher’s wife. Gallagher himself then got on the line.

“All he kept saying was ‘I’m sorry, I’m sorry,’” Greg remembers.

Wednesday morning, a police color guard escorted the hearse to the Holy Name of Mary Church in Valley Stream. The officers of the 77th Precinct stood at attention in white shirts and white gloves. They saluted as Brian’s flag-draped coffin was carried up the steps.

During the Sign of Peace, Greg went down the right side of the aisle and shook hands with one cop after another. Rathbun was hunched off to the left with his wife, sobbing. Gallagher sat in the back, gripping the pew before him with both hands, his eyes welling with tears.

Just before noon, the coffin was carried back into the sunlight. The officers again saluted, and many of them went off to start another tour at a stationhouse that is expected to see as many as twelve more indictments. Gallagher, Rathbun, and the other indicted cops hurried away to make a 2 P.M. court hearing.

With a squad of leather-jacketed officers on motorcycles clearing traffic, the O’Regan family followed the hearse to a cemetery in Westbury. There, they each laid a red carnation by the grave of the man who had left Valley Stream to be an officer in the Police Department of the City of New York.

“You tell me why I did this,” Brian O’Regan had said one week before.