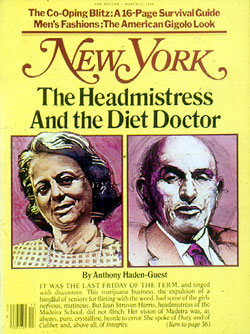

From the March 31, 1980 issue of New York Magazine.

It was the last Friday of the term, and tinged with discontent. This marijuana business, the expulsion of a handful of seniors for flirting with the weed, had some of the girls nervous, mutinous. But Jean Struven Harris, headmistress of the Madeira School, did not flinch. Her vision of Madeira was, as always, pure, crystalline, hostile to error. She spoke of Duty, and of Caliber, and, above all, of Integrity.

But—some of the girls noticed—Jean Harris seemed unusually ill at ease. Run-down. That Friday, she dropped in at the infirmary, where a nurse gave her some shots for anemia. She proceeded with the day’s business calmly enough—she had announced that she intended to stay on campus for the three-week break—but, showing some distress, she unexpectedly canceled a 3:30 appointment.

The girls left Madeira that Saturday morning, except for some 40-odd juniors who had holiday internships on Capitol Hill. One of the juniors went to see Jean Harris on Sunday. Jean Harris lived in a two-story red-brick house called “The Hill,” and she had said that it was “always open.”

It was seldom open quite so literally, however. The door was open wide, the girl says, and the usually meticulous place was the biggest mess you can imagine. “Clothes were thrown all over the floor,” she recalls, “and the kitchen looked as if she hadn’t been in there for a week.” Jean Harris herself was nowhere to be seen, and the girl departed, puzzled, her problem unresolved.

Jean Struven Harris spent much of Monday writing. She wrote a letter, extraordinarily long and rambling, and then she put the sheets together in no particular order and stuffed them into a manila envelope. She addressed the letter to Dr. Herman Tarnower and dropped it off at the small post office on the Madeira campus.

Just to make completely sure, she sent it by registered mail, which requires a signature. No prevarications, no excuses. Herman Tarnower, best known as the millionaire creator of the “Scarsdale Diet,” had been her lover for fourteen years. But, since her coming to Madeira, perhaps even since his newly found celebrity, he had been slip-sliding away. There was Another Woman. Her shining world—Duty, Caliber, Integrity, those safe and shining abstractions—lay about her in ugly shreds and splinters.

That night Jean Harris was expected for dinner with John and Kiku Hanes. It was a typical “intelligent” Washington dinner, a sit-down for fourteen, nothing to do with Madeira, no alums, no parents, just well-informed people, like Jean Harris.

“I had spoken to her the day before,” Kiku Hanes says. “She was looking forward to it. There was an empty place, but I wasn’t worried at all. I know what being a headmistress is like.”

In fact, Jean Harris did dress as if for dinner: a trim ensemble of black jacket, white shirt, black skirt. It seems she changed her mind. She wrote some further notes, these detailing her inner ferment, and she scattered them around the small and comfortable house that (she wrote) she had no intention of ever seeing again.

Jean Struven Harris fetched her gun, a Harrington & Richardson .32-caliber revolver, which she had acquired a couple of years back at Irving’s Sport Shops in Tysons Corner. It was still in its box. She dumped it in her car, an unshowy blue-and-white 1973 Chrysler, and took off on the five-hour drive.

The weather, so unseasonably mild, broke while she was still on the road. An inconsiderate thunderstorm lashed the rich suburbs, and she arrived to find Dr. Tarnower’s house, that half-million-dollars’ worth of neo-japonaiserie where she had spent so much pleasant time, muffled with black and steaming blankets of rain.

The burglary call came through to the Harrison police at 10:59 P.M. When he arrived, patrolman Brian McKenna found the angular body of Herman Tarnower, 69, sprawled crooked and awkward in an upstairs bedroom, dying in beige pajamas. Tarnower tried to speak, but managed only random sounds. Jean Harris stood there, distraught, her natty outfit rain sodden. The headmistress of Madeira School, whose roster of pupils, past and present, reads like a Fortune-hunters’ 500, was booked for Murder Two.

The headmistress and the millionaire doctor, the headlines ran.

Certainly, it has a better sound to it than the sleazy mayhem that usually occupies the tabloids and the TV news. There’s a ring of that comfortably titillating British detective-story world, those clubs and country houses where the upper middle classes plot one another’s baroque demises. No wonder that cigar box of a courtroom in Harrison allured such media luminaries as Shana Alexander (who wore black mink), sitting behind the defendant, just as she had done through the seven months of the equally classy Patty Hearst trial: the Shana Alexander position.

And add to Agatha Christie pinches of Cheever and John O’Hara. Consider the venues: Shaker Heights, Cleveland; Grosse Point, Michigan; Chestnut Hill, Philadelphia; a smart girls’ schools in Virginia; and Westchester County. Was ever a crime of passion more fashionably suburban than this?

But there is much more to this odd affair than class. Kennett Rawson, who published the Scarsdale diet book in hardback, finds himself bewildered. “Tarnower was not a man who anybody ever got anything out of,” he says. “That’s what makes it so incongruous that he was involved with these torrid love affairs.”

A prominent Madeira alumna is equally puzzled. “Mrs. Harris is most genteel,” she told me.

“She’s so very proper. The whole thing sounds so incongruous.”

The echo proves to be eerily appropriate. Yes, this case does turn out to be a most incongruous affair.

The romantic liaison of Jean Struven Harris and Dr. Herman Tarnower had begun, friends say, fairly soon after her 1966 divorce. There was a certain symmetry to it. Jean Harris was a director at the Springside School, a girls’ academy in Philadelphia. She and her two sons lived in a house in one of the city’s fancier neighborhoods, Chestnut Hill. She dressed with conservative chic and took care to keep abreast of the times. A divorcee in her early forties, with her high forehead, fair hair, and pale blue eyes, she cut a fine figure. One observer saw a resemblance to middle-period Bette Davis.

Herman—“Hi”—Tarnower was in his mid-fifties. He appeared to most an austere and private figure with no capacity for small talk. He came across as a warmer man to his patients at the Scarsdale Medical Group, which he had founded with Dr. John Cannon, and which kept him comfortably rich. “He always had very attractive women friends,” says Mrs. Arthur Schulte, who had known him for years. “He was always very generous with time and money. But he never married. I don’t know why.”

It was a deeper symmetry than this. Tarnower and Harris were, in certain respects, similar. Both had achieved their positions with huge expenditures of effort, and both masked their formidable competitive streaks with a manner of cool self-containment. Quite fittingly, their relationship was, it seems, both decorous and intense.

Herman Tarnower came from a solid middle-class Jewish family in New York. And he was a driven man from the beginning. Ignoring his father’s prosperous hat-manufacturing business, he studied medicine at Syracuse, graduating in 1933. A residency in Bellevue was followed by the first of his travels, a 1936–37 postgraduate fellowship: six months studying cardiology in London, and six months in Amsterdam.

In 1939, Tarnower was back home, an attending cardiologist at White Plains Hospital. War came. The end of the war found him a lieutenant colonel stationed in Japan. He was a member of the Casualty Survey Commission, the casualties in question coming from Hiroshima and Nagasaki. The experience, understandably, marked him. He would talk of it frequently.

In due course, Herman Tarnower returned to White Plains Hospital. He moved to Scarsdale. In quiet, exemplary fashion, his career progressed, carrying him toward his meeting with Jean Struven Harris.

Jean Witte Struven was born in 1924 and grew up in the fashionable Cleveland suburb of Shaker Heights. She was educated at a private school, the Laurel School, and spent the war reading history and economics at Smith. Contemporaries say that she was ambitious, organized, and personable, but showed scant interest in the pleasant dillydallying of college days. She graduated magna cum laude. Shortly thereafter, she married the good-looking son of a Detroit industrialist, James Harris. They settled, of course (seeing that low-rent neighborhoods do not figure widely in this story), in Grosse Pointe, Michigan.

The Harris family was every bit as socially registered in Detroit as the Struvens were in Cleveland, but James Harris was a second son, and well-bred does not invariably mean well-heeled, nor does the whole of Grosse Pointe look custom-built for the Ford family. As Jane Schermerhorn, editor of the Detroit Social Secretary, put it, the residents mostly “aspire to the life-style they can’t afford.”

The Harrises moved into a two-story “colonial” house on Hillcrest, a narrow road lined with trees and closely spaced houses, which runs into the back lot of a Sears shopping center. In 1946, four months after her marriage, Jean entered the world of private education, teaching history and current events at Grosse Pointe Country Day School.

This was in keeping with her ambitions. “It’s always been a fashionable school,” Jane Schermerhorn says. “If you couldn’t send your children to Dobbs Ferry or Andover, you sent them there. Edsel Ford worked very hard for the school and all his boys went there.”

She took some time off to raise her sons, David, born in 1950, and James, born 24 months later, but remained at the school for the next several years. Bertram Shover, then the lower-level director, remarks that “she was definitely ambitious and wanted to become more than a first-grade teacher.”

James Harris, meantime, had also taken a job, though not necessarily at a level guaranteed to make an ambitious Grosse Pointer swell with pride: He became a supervisor at the Holly Carburetor Company. It seems he simply wasn’t that ambitious. “James Harris wasn’t as forceful as she was,” Bertram Shover says, “but a lot more fun to be with. I liked him a lot.” A neighbor spoke directly to the point. “All I’m saying is that everyone loved him,” the neighbor said. “She was very pretty and very brilliant, but everyone loved him. He was a nice, quiet man.”

Jean Struven Harris, however, was forging ahead. She was a good teacher, impressing parents with her creativity and administrators with her competence and drive. Although teachers made less in the private sector than at the public schools, there were other, very tangible advantages. The Harris boys were enrolled free, for instance, and, as Shover puts it, there was “social prestige with the job; an entry into social circles.” She became increasingly active in such pleasant milieus, and increasingly independent. Shover remembers that in 1958 she went to Russia, quite alone, and gave a well-attended lecture about her experiences on her return. Jean Harris was very good at giving lectures.

In 1964, however, Mrs. Harris had to deal with certain obstacles. She was one of three recommended as Bertram Shover’s assistant, but lost by a nose. Also that October, she filed for divorce, complaining of “extreme and repeated cruelty.” It was stated that the weekly salary of James Harris was $203.80 gross, $165.30 net, and that he had a net worth of $27,000, including a $900 Renault. Jean Harris—who listed her own salary as $132.90 per week—asked for custody of the two boys and possession of the house, upon which she requested that James Harris continue to pay the mortgage. James Harris agreed to the cruelty complaint but said that his wife was guilty of the same. The court found against him, and ordered that he make weekly payments of $54. The divorce was granted February 23, 1965. In June, Jean Harris decided to leave Grosse Pointe. In the years ahead she was often to allude, with justifiable pride, to the way she brought up her boys. Of James Harris, who died in 1977, she seldom, if ever, spoke.

Jean Harris moved to Chestnut Hill, Philadelphia, in September 1966, and took up a post as director of the middle school at the Springside School for girls. She is remembered as rather a formidable person there, a keen administrator and a tough disciplinarian. “It was a reign of terror. We were glad when she left,” one of her pupils told a Philadelphia reporter. Her views regarding cigarettes, let alone beer or pot, were inflexible, and her eye vis-à-vis dress lengths was as beady as Women’s Wear Daily’s. More ominously, one pupil reports that she was “very, very high-strung.”

Socially, she was active, of course. Philadelphians recall frequent visits from one escort in particular: Dr. Herman Tarnower. To the few permitted any insight into the relationship of these two very private people, it seemed a fitting arrangement. True, Tarnower was a decade and a half older and showed every sign of being a committed bachelor, but he had a shrewd eye for a handsome woman.

Impelled perhaps by memories of Japan, he had recently taken one such lady friend to the Far East. They had made the then unusual trip to mainland China, and Tarnower would sometimes discourse on his dinner with Zhou Enlai. It was this woman friend who was now being phased out in favor of another woman: Jean Struven Harris.

It was true that those who didn’t know the vulpine and thin-featured Tarnower often found him forbidding, what with his formal manners, his probing stare, his correct English clothing. “I don’t think anybody knew him very well,” says Kennett Rawson. “He was very self-contained, very opinionated. Nobody talked to him. He lectured you. He reminded me of the Hollywood idea of a Prussian major general.” Said an acquaintance, “He hated chitchat, gossip, small talk.” But what of that? There wasn’t too much of the chitchatter about Jean Struven Harris.

Also, the eminent cardiologist’s intimates had a different view. What else are intimates for? “He was a very outgoing guy. A very humorous guy,” says architect Robert Jacobs, a close friend of Tarnower’s. Jacobs attended many of the doctor’s excellent dinner parties, where the wines would be chosen with expertise, and the food—prepared by Dr. Tarnower’s French-born cook-housekeeper, Suzanne van der Vreken—was likewise. The parties were also where the ascetic gourmet’s guests—“usually six to eight, all interesting people”—would eschew froth, hewing to the issues of the day. Mrs. Schulte also notes an absence of frivolity, saying that Tarnower “didn’t like fiction. He liked reading biography, history, books about people who had achieved something, made a difference in the world” but agrees that the doctor always liked a laugh. “He had a very quick sense of humor,” she says. “My husband had been his closest friend for 25 years. They used to throw semihumorous insults at each other.”

Here are hints of the singularity that put off so many, but drew some—including, one must presume, Jean Harris—so close. Those superlative medical skills, which showed the kindlier side of Tarnower’s nature—“He was one of the last old-style doctors,” says a patient, “he really cared”—ran alongside a sort of competitiveness, a controlled aggression.

To a certain extent, this showed itself in traditional upper-middle-class pursuits. Tarnower drew most of his friends from either his patients’ register or his country club, the Century, which is to say, the same list. He was a seventeen-handicap golfer. “He was excellent at gin rummy,” says Robert Jacobs. “He was excellent at backgammon. He was excellent at everything he did.”

And some of the things he did were more exotic. He loved to travel. The travels yielded objets d’art. Tarnower brought back numerous Buddhas from the East, for instance. One such holy figure, covered with a crackle of gold paint, sits on an islet in a pool on Tarnower’s cultivated six-acre estate. The doctor would sometimes row across and contemplate. Agatha Christie herself would have gloried in the touch.

Hi Tarnower’s other pursuit was in a contrary direction. He liked to hunt. He fished for marlin in the Bahamas, bonefish off Mexico, shot birds in North America, and went on six African safaris with Arthur Schulte alone. There are few varieties of legal game that the imperious hat manufacturer’s son did not, at one time or another, add to his bag, the choicer items being brought back so that they might adorn his Purchase house, alongside the stone and golden Buddhas and the large collection of guns.

Jean Harris, understandably, was fascinated. The relationship grew deeper. When she left Springside in 1972 to become head of the Thomas School in Rowayton, Connecticut, Philadelphia acquaintances speculated that it was to be closer to Tarnower. She bought a house in Mahopac, just a 45-minute drive from both the doctor and the school. (This is the house in which her son, David, a banker in Yonkers, now lives. It is also where Jean Harris had been staying during the trial hearings.)

Thomas was a private girls’ school and was in a sorry state. It was a bad time for private schools generally, with enrollments declining, and the posh boys’ schools—Exeter, Saint Paul’s, Choate—going co-ed. Jean Harris was supposed to turn it around. The reputation she earned was familiar—efficient, though inflexible—but there was a disturbing new ingredient. She could be temperamental, sources say. Moody. A former staffer said that she would “scream at students.”

In 1975, at any rate, the Thomas School closed. Jean Harris, whose sons were now both in their twenties, left private education and took a $32,500-per-year job with the Allied Maintenance Corporation. Allied does such necessary, but unglamorous, tasks as supplying janitors to Madison Square Garden. Jean Struven Harris of Shaker Heights, Grosse Pointe, and Chestnut Hill, was a supervisor of sales. The money was good, but, after eighteen months, when she heard that there was an opening at the head of the Madeira School, one of the glittering prizes of the profession, she did not hesitate before applying.

The Madeira School was started by Miss Lucy Madeira in a Washington, D.C., townhouse in 1906. Considering what was to come, it is a pleasant touch that Lucy Madeira was a determined young woman with a strong inclination to the theories of Fabian socialism. Portraits of Madeira show a pleasant Late Victorian face with a smile of steely shyness and the round, thin-rimmed specs so popular later with that girl’s school problem, the Woodstock Generation. Her will is still much a factor in the school. “She had these sayings,” an alumna tells me, “like ‘Function in Disaster’ and ‘Finish in Style.’ Just mention them to any Madeira girl—she heard those phrases over and over and over again.”

The first disaster was the Depression. Lucy Madeira wished to move, expand. Funds were not forthcoming. Help came. Eugene Meyer, owner of the Washington Post presented several hundred acres of unused woodland alongside the Potomac, which is where Madeira School is today.

In many respects, the Fabians might be pleasantly surprised by the New Woman as she has emerged from Madeira. Alumnae include Eugene Meyer’s daughter, Kay Graham; Ann Swift, now a diplomatic hostage in Tehran; and Diane Oughton, a member of the Weatherman collective, who died so brusquely in an exploding Greenwich Village townhouse and who, friends say, cherished fond memories of the school to her rigorously Marxist end. Students today include the daughters of ABC reporter Sam Donaldson, commentator Eric Sevareid, Republican senator from Wyoming Malcolm Wallop, and a granddaughter of Nelson Rockefeller.

That great Fabian George Bernard Shaw might have found himself more ambivalent about other aspects of the school. It is, of course, true that the first visible sign on the campus reads, STOP: HORSE CROSSING, just as it is true that the most splendid new building is a $3.5-million indoor riding ring, but Madeira alumnae are sensitive to the merest hint that it’s a fairly fancy setup.

“We are not a finishing school,” alums told me over and over. Madeira has a one hundred percent college-entrance rate. Madeira is practically a natural resource where the Ivy League is concerned. Madeira integrated during the last decades, the administration told me, and now has twelve black pupils. Indeed, they are actively looking for more, but there is a sort of problem, given the fees—“$6,100 a year for boarders, after taxes”—and the shortage of scholarship endowments. As to the other all-girl schools, Madeira tends to be a bit sniffy. “Foxcroft?” said one. “That’s a glorified riding academy.” I repeated this remark to another alum who had, till then, been talking of Madeira rather as if it were the Académie Française. She struck like a terrier embedding its teeth in my calf. “We always beat Foxcroft,” she said.

But, for all its equable progress, some felt that the years since Lucy Madeira departed had represented a decline. Many of the problems had been classic. One senior official, it was found, had a drinking problem. The late sixties and early seventies brought contemporary travails. “We could get expelled for smoking a cigarette,” one ex-pupil remarks. “But there was no shortage of druggies.”

The headmistress then was Barbara Keyser. Barbara Keyser was a girls’ school headmistress in the indomitable British mold—unmarried, wholly engrossed in her role. Many swore by her, but some were intimidated. “She was really quite a threatening figure,” one pupil says. “She looked and acted like a drill sergeant.”

Many say that girls’ schools in those turbulent years needed a hand. It was, after all, at this time that a dead baby in a plastic bag was discovered at that genteel Connecticut school, Miss Porter’s. Anyway, when the problem did come to Madeira, it was less natural, more horrible. A man had taken to roaming the grounds. It seemed to go on and on. A malaise overhung Madeira until the deranged male was caught, and locked up.

What happened next is not crystal clear. At any rate, the man was at large and the school wasn’t told. Hitherto harmless, he struck. One of the pupils was assaulted and tied to a tree. She died of exposure. It seemed that the sickening event preyed on Barbara Keyser’s mind. She did everything that could be done, but the memory didn’t leave her. It hung about the school like memories of a bad dream.

Barbara Keyser retired three years later, in 1977. The board of alumnae in charge of choosing a successor thought long and hard. They decided they knew exactly what they were looking for. A woman was needed with managerial skills appropriate to the modern business of education. Also, one of them says, “we wanted somebody womanly.”

There were 100 applicants. “The committee investigated in depth,” an alumna says. And Jean Struven Harris seemed perfect. The business background at Allied Maintenance. The marriage, the family. Nobody, it seems, got an adverse reading from the former schools. The Thomas School, anyway, was closed. Jean Harris was appointed headmistress of Madeira, taking a salary cut of some $10,000 a year. Things seemed rosy.

Things were less rosy between Jean Harris and Herman Tarnower. They were still close. Tarnower had accompanied Harris to the 1974 graduation ceremonies at the Thomas School, for instance, and she frequently left Madeira for weekends in Purchase. But two things were happening. Herman Tarnower’s affections were quite perceptibly cooling. Also, Herman Tarnower had become a celebrity.

The celebrity business first. There was nothing new about the Scarsdale Diet, of course. Tarnower had been circulating it as a single mimeographed sheet for years, though his expertise was not the belly but the heart. Yet the diet got good word of mouth. In early 1978, the Times featured it in a piece, mentioning especially its exemplary effects on a vice-president of Bloomingdale’s.

This article was read by Samm Sinclair Baker. Baker says he has written 27 books. A couple of mysteries first, then five books on Creative Thinking, and so into medicine by way of “a book on skin problems written with a couple of dermatologists.” The Scarsdale Diet was a natural.

“We met in May ’78 and we liked each other immensely,” Baker says. “He was a total gentleman. Very straight arrow.” He discovered that Tarnower had discussed the idea of a diet book with his neighbor, Alfred Knopf. “But Knopf was discouraging,” Samm Sinclair Baker says. He discussed things with Tarnower, mainly the strictly formal problem of how to turn a mimeographed sheet into a full-length book—“I said what we will do is answer all your readers’ questions as though they were your patients”—and, writing night and day over four months, they delivered the book on October 1. “We were both workaholics,” Baker concludes with satisfaction. The book, which carried a prominent acknowledgment to Jean Harris, sold 750,000 copies in hardback, two million in paperback, and made Herman Tarnower very celebrated and even richer.

Herman Tarnower himself, a meager performer on talk shows and poor at public appearances, tended to play the thing down. Indeed, he probably felt ambivalent about the unexpected stardust. A friend, hearing that he was to deliver a speech in Washington, once asked what branch of cardiology he would be discussing.

“Heck no,” Tarnower said. “Nobody wants to hear me on the subject of cardiology. It’s about nutrition.”

Dr. Tarnower’s new celebrity made another change that much more conspicuous. Over the last couple of years, Hi Tarnower had begun to date another woman. She was Lynne Tryforos, 37, a comely blond employee of his Scarsdale Medical Group. She was two decades younger than the woman Tarnower had refused to marry for a dozen years.

The new affair seemed cruelly public to Jean Harris. Tarnower would take Lynne Tryforos to dinner parties like the one given by Bernard “Bunny” Lasker, former chairman of the New York Stock Exchange—the sort of upper-echelon Westchester and New York functions to which he had taken Jean Struven Harris.

Jean Harris compressed her private griefs. “Integrity” was as stressed as ever in her Monday-morning talks to the girls. If anything, she was retrenching. Last fall she was applauded by parents for announcing that she was putting that insidious district, Georgetown, off limits. She seemed to be ever more vigilant that the girls not succumb to weaknesses of the flesh.

Not everyone was favorably impressed. Some parents—like a father whose daughter was suspended for quaffing a glass of beer—were irritated by her inflexibility. The girls, by and large, decided that she was a cold fish. A few sensed something else. “She was really always a nervous wreck,” announces a pupil. “Pulling at her hair, walking bowed over. She could never joke around. I’ve never seen a woman so ill-assured. One time a kid asked some critical question, a ridiculous question. She cried onstage in front of the whole school.”

Last December, Hi Tarnower shot quail at the South Carolina ranch of Christian Herter Jr., then calmly took Jean Harris to spend Christmas and the New Year with the Schultes in Palm Beach. They read, talked, fished. Tarnower worked avidly through the Manchester book on General MacArthur. Arthur Schulte, something of a power in banking circles and an old friend of these two icily self-contained people, didn’t feel that anything was other than swell.

Toward the end of January, Hi Tarnower took another trip. He went to Montego Bay, Jamaica. His companion was Lynne Tryforos. Some sort of decision was approaching. This last Tuesday, March 18, was to have been Tarnower’s seventieth birthday. A dinner party was planned. His guest was to have been Lynne Tryforos.

Lynne Tryforos was also among Tarnower’s dinner guests—they had all left a couple of hours earlier—the night Jean Harris arrived in the raging rain. When the police came, Jean Harris spoke in broken and contradictory fashion. “I shot him—I did it,” she said at one point. But she also said that she had asked him to kill her.

If Joel Aurnou, Harris’s lawyer, can prove that such was indeed her intention, the charge of murder automatically gets lowered to one of manslaughter. Jean Harris sits and waits, her pale blue eyes unreflecting as china. She laughs aloud when something funny is said, but kindness makes her weep. Mostly, though, even in the courtroom, even in the sanitarium, she has a forlornly elegant dignity. It is as though those late Victorian Madeira maxims shield her still. Function in Disaster. Finish in Style.

Perhaps all she wanted to do, as schoolchildren say, was teach Hi Tarnower a lesson. Certainly she cut Tarnower off just as an apotheosis of sorts was approaching this ambitious man. On April 19, Dr. Charles Bertrand, president of the Westchester County Medical Society, was to have presented Tarnower with an award at a very grand dinner. A cardiac center was to be named after him. The cardiac center, like the jail in which Jean Harris was held, was in a place called Valhalla.

Dr. Bertrand sighs. The Thursday before the murder, he had been chatting with Tarnower, who said he was about to start another book.

“What’s the title?” asked Bertrand.

“How to Live Longer and Enjoy Life More,” said Hi Tarnower.

Lucy Madeira’s sayings have a more durable ring.