I first learned of the natural-gas land rush that is gripping some of the most scenic areas of New York and Pennsylvania when a thick envelope arrived in my upstate mailbox. The letter, signed by someone named Daniel F. Glassmire VI, was written in an ostentatiously baroque language that, as even he seemed to acknowledge in a dense preamble, could be mistaken for gibberish. I didn’t understand it at all until I corrected his punctuation and read it out loud.

“Hello,” it began. “My name is Danny, a young man in the way of prospecting, for about 14 months wet behind the ears but now and again really sharpening this experience of newness. Through all that—or anything else of importance (or trivia)—I would really like you to get an involved look-see into the dimensions of this Leasing proposal … I would clearly within this matter really look forward to meeting, if it would be possible, you at your residence for as long as you like, and for remaining in communication as many times as would follow for you in the best assurances of clarity. You are the decision-maker. The only possible goal would be to keep to your decision. What I have to show you is a mere compliment to where you go in decisions, and what is said through any presentation only has influence through your clear and finalizing decisions. It should hopefully be fun enough, as it ought to remain, regardless of turnout, as the stuff of interest.”

My boyfriend and I own a former dairy farm near Margaretville, New York, a tiny Catskills village in Delaware County. Half its 95 acres are rolling pastures. The rest is a dense forest canopy, the teeming home to enough bobcats, coyotes, bears, minks, and game birds to fill a season on the Discovery Channel. We entertain hippie dreams of one day raising sheep and goats (or quince or tilapia or anything organic).

From stoop to porch, the drive is exactly three hours. Before 9/11, that was generally considered too far away. So we got the place—and a run-down six-bedroom Victorian farmhouse—for next to nothing. Now, thanks to Al Qaeda, people like the feel of distance. They’ve pushed up prices tenfold. Still, it’s nothing like the Hamptons, at least not yet. There’s no high-stakes social swirl, no see-and-be-seen. We spend our evenings on our respective porches thankful for the unspoiled mountain expanses and sagging dairy barns that separate us, no light but the twinkling stars.

Almost two miles below our farmhouse, it turns out, is a mother lode of natural gas we knew nothing about. Glassmire enclosed a proposed lease, our names already inked in. It offered $125 per acre. This was just a bonus for signing. If the wells hit, we’d also get 12.5 percent in future royalties. This, he assured us, was likely to make us comfortable. He didn’t say how comfortable, but among the many things he shows landowners is a handwritten formula titled “Estimating Natural Gas Royalty.” Wells on our farm might produce 5 million cubic feet of gas per acre per day, it says. At today’s prices, our projected share could be worth $9,000 every day. That’s over $270,000 a month. If each well’s lifetime production is between 3 billion and 4 billion cubic feet of gas, as one oil company has projected, we’ll have a tax headache in the $7 million range.

Let’s say he’s grossly overinflated the potential windfall. Cut it in half, cut it to a tenth, it doesn’t matter. It is very much the stuff of interest.

But by the time I called him back, Glassmire had been reassigned to points west, staking out parcels in rural Susquehanna County, just across the border in Pennsylvania. “They pulled the plug on your prospect,” he told me apologetically. “They weren’t confident about the geology, which was too bad, because I had a thousand acres ready to lease.” He named names, including the owners of just about every rolling knob of the Catskills visible from my porch. I asked him what could be wrong with the geology, but that was above his pay grade. “That’s the sparkling mystery of it—is there stuff under those grounds?” he said. “Could be. Or maybe somebody got fired. Maybe they changed their mind. Hopefully they’ll be back.”

Come summertime, they were circling again. The Gas Era is coming, and the landscape north and west of the city will inevitably be transformed as a result. When the valves start opening next year, a lot of poor farm folk may become Texas rich. And a lot of other people—especially the ecosensitive New York City crowd that has settled among them—will be apoplectic as their pristine weekend sanctuary is converted into an industrial zone, crisscrossed with drill pads, pipelines, and access roads. The struggle has already begun between those who will take the money and those who won’t—between “locals” and outsiders, optimists and pessimists, them and us.

Danny Glassmire was an avatar of this new world. I called him again, and he read my apprehension correctly, though he himself saw little reason to worry. He is possessed of a salesman’s ability to see the bright side. “I’m deeper in the prospect now,” he said. “I’d love to show you around.”

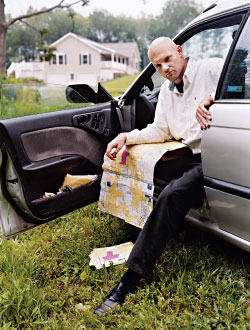

So a few weeks ago I drove to Binghamton to see the gas prospect where it is most mature. Glassmire operates out of a decommissioned Holiday Inn across from the SUNY campus. His room was around back, past the garbage Dumpster. A do not disturb sign was fixed on his knob. Inside was a tableau from a Maysles film. Legal documents exploded out of folders and boxes that lined the walls. Clothing was lain in heaps on the floor and lolled from half-open drawers beneath the television stand. Books were everywhere. He dotes on a certain vein of authors who are as attuned as he is to the chaotic potential of words: Faulkner, Cormac McCarthy, and “DFW,” as he calls David Foster Wallace, his favorite author of all time.

His bed was layered in large tax maps—Xeroxed pieces assembled with tape into blurry wall-size collages. On the desk, along with a freezer bag of colored markers, was a clear plastic pitcher filled with ice into which he’d nestled an open Bud Light Lime.

“I guess Holiday Inn took the old ice buckets when they left,” he said, offering me a warm beer and putting another in the pitcher for himself. “Must have been emblazoned with the old brand.”

It was a Sunday afternoon, and Glassmire, who is 26, was in slim corduroy pants and a Led Zeppelin T-shirt. He’s tall and skinny and driven by a twitched-up energy that makes him talk in fast-forward about a dozen thoughts at once. This made him difficult to understand. He recognized people might think he’s odd. “I’m like one of those kids who’s gainfully, like, autistic or something. Like I have my own dimension,” he explained. As he said this, his eyes shimmered and glowed. Despite a tufty, thin-on-top hairstyle (he is his own barber), Glassmire is quite handsome. (“For a landman,” Glassmire agreed, “I think I’m pretty.”)

He smoothed out a large map. “Somewhere in this map is the absolute core—the absolute core—of this prospect. And I’m going to lease it.”

Geologists have known about the gas for more than a century. It is held in an enormous rock formation known as the Marcellus Shale, formed some 385 million years ago in the bed of a shallow inland sea that once stretched from south of Albany down to West Virginia, from the Hudson Valley into the middle of Ohio. Over time, the sediment-rich sea was buried, as tectonic collisions pushed the Appalachians into existence and the Catskill Mountains, a result of a single collision event, rose up in the north. The old seabed, meantime, came to rest almost two miles below the Earth’s surface. Along the way, it was subjected to increasing temperatures and compression, changing the sediment first to a waxy material from which oil can be extracted, then into natural gas and shale stone.

According to Dr. Gary Lash, a geologist at SUNY Fredonia who studies the Marcellus, it holds possibly the largest reservoir of natural gas ever discovered in America—five times larger than the previous granddaddy, the Barnett Shale, which was first identified beneath Fort Worth, Texas, in 1981 and is now in full production. There are 500 trillion cubic feet of gas in the Marcellus, enough recoverable fuel to meet all of the nation’s needs for two full years. So much is bubbling below the mid-Atlantic hills, in fact, that in the otherwise unremarkable town of Windsor, it sprays from bathroom faucets.

The Marcellus was largely ignored over the years because it is difficult and expensive to exploit. Rather than gathering in handy pockets, the Marcellus gas is tightly trapped in the pore spaces of the stone. But a new drilling technique known as horizontal hydraulic fracturing allows extractors to slam chemically treated water into the stone, breaking it up and pushing the gas into pockets for easy recovery. That, combined with a tripling in gas prices over a decade, has made the Marcellus an obsession for gas companies. In a sudden spasm of competition, hundreds of landmen have moved into motels throughout the Catskills and Poconos in the past few months. Their rivalry is fierce. The signing bonuses they’re offering for a five-year drilling lease have gone from $5 an acre last year to $3,000 or higher in some communities. That’s more than it took to buy the land outright just a few months back.

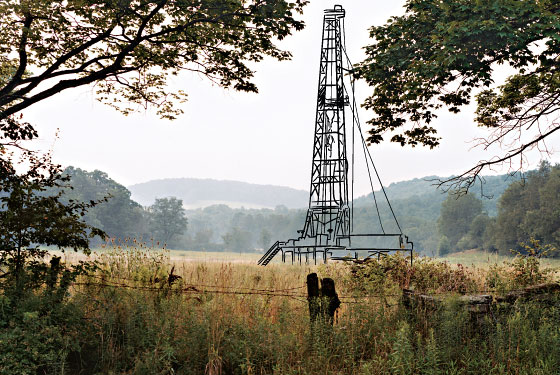

Already perhaps 60 oil and gas companies have submitted drilling applications in New York and Pennsylvania, says Paul Swartz, executive director of the Susquehanna River Basin Commission, a multistate and federal governmental agency protecting aquifers in 67 counties. “We’re only now at the beginning part of what is going to be an enormous activity here in the years to come,” he tells me. In northeastern Pennsylvania, the drilling rigs have already begun operating. That hasn’t happened yet in the main New York gas counties of Broome, Sullivan, Otsego, Chenango, and Delaware. But this summer, Governor David Paterson signed a bill streamlining the permit process, so groundbreaking could begin in the spring.

Meanwhile, county clerks’ offices report being choked with landmen filing deeds. “It’s a gas rush, that’s what it is,” says Ronny Murphy, a real-estate broker in Bethel, New York, about 100 miles upstate on Route 17. Dan Rather, Debra Winger, Jennifer Lopez, and Marc Anthony all weekend nearby. Already a massive infrastructure is being put into place to anticipate the march of wells across the Catskills. “Right now, they’re bringing gas pipelines through. Every ten or fifteen minutes, by my office, the trucks come by. Up in Callicoon, you see the swath. They’re cutting this huge channel and laying new pipe. Eventually it will grow over again, but right now it’s Oh my God.”

Once those wells hit and gas starts reaching the marketplace, one thing is certain: Outrageous sums of money will flow to some of the poorest communities in the area. “We’re talking about a lot of money,” says Tom Murphy, a Penn State educator who helps landowners understand their rights. “We’re on the early side of this, so people are still trying to get their hands around how big this impact will be. But in Pennsylvania alone, you could be looking at half a trillion dollars or more over the course of this play as it develops here in the state—big bucks.” In some parts of Pennsylvania, faraway investors have been snapping up land with dreams of becoming gas magnates, Murphy tells me. “People are buying it sight unseen. It doesn’t even matter what it looks like. What matters is what’s 8,000 feet underground.”

Still, when Glassmire’s letter arrived, it felt like a draft notice. Just last year, we were dodging bullets in another energy uprising. Wind-turbine companies had leased several nearby farms with a plan to march towering pinwheels across their mountain ridges. Most of our friends with second homes in the area abhorred the thought of these structures dominating the horizon. They wrote fulminations to the local paper and circulated videos showing how much taller these things were than the Statue of Liberty, how their blinking lights would perforate the evening sky. Real-estate brokers warned that tourists would abdicate and property values plummet. They pressed for a moratorium and possibly an outright ban in defense of what they began calling “the viewshed.”

Many year-round residents had a different perspective. Besides being clean energy, turbines meant needed income, a last chance to save the family farm. They rejected the suggestion that their sagging barns were someone else’s visual entitlement. As the two sides went to battle in Andes, Bovina, Meredith, Roxbury, and Stamford, the mutual animosity between locals and “flatlanders” was laid bare, with ballot-box shenanigans, shoving matches, and ad hominems. In most instances, for better or worse, the flatlanders have prevailed (for the record, as green fetishists, my boyfriend and I quietly supported the wind farms).

But Glassmire told me he hadn’t encountered much opposition. Only one of my neighbors told him to get lost. Since then, he said, a landowner in Western New York had chased him back to his car with a baseball bat, but mostly he worked his charm to good effect. “I always do the There Will Be Blood impression. I’m like, ‘You have your milkshake, and over here, this is my milkshake, and my straw goes into your milkshake and sucks it up.’ ” He laughed Daniel Day-Lewis’s laugh, then reeled himself in. “No, really. I was leasing you and Delaware at $125. That was the most I was able to offer. But here, it’s $2,500—they’ve added two zeros. The competition is great. It’s the most rural kind of beautifious, green-heaven kinds of places, overflowing with these companies. It’s good for the area, economy-wise. Now probably it’s fair to say the sky’s the limit—that’s the challenge. There’s the terrestrial versus the beyond. We’re going beyond.”

I asked him to explain the environmental impact. “I would say you’d have a brief world of chaos and noise for some weeks,” he said. “Then they take away the rig and you have a well—a real innocuous well, the size of a small car.”

When I looked up pictures of the drilling rigs on the Internet, Glassmire’s vague description became alarmingly concrete. The installations are significant-size industrial parks. Including access roads and parking areas, a drill pad takes up several acres, with three or more physical structures the size of shipping containers and an Erector Set–style tower standing perhaps 40 feet tall. Trees are removed, entire slopes are leveled. The facilities wheeze and off-gas, and frequently throw off huge flames. Next to them are large pits holding millions of gallons of contaminated water.

Once drilling is completed, which could take a few months, much of the physical infrastructure is removed and the ponds are drained, but the area doesn’t return to pasture—it is still a bustling industrial site. Jim Waters, executive director of the Catskill Forest Association, told me he believed these drill heads can be hidden unobtrusively in the woods—that we could actually specify wellhead placements. Glassmire seemed to say anything was possible in the Marcellus play. But he pointed out that each wellhead will be connected to the next by a pipeline, which creates its own racket. Enormous pistons, driven by nonstop diesel-fired compressors, are used to keep the gas moving downstream. The vibrations can be felt from 1,800 feet.

For Glassmire, that’s just the way life is. “I don’t know if there’s any way of avoiding it. You mostly can only control your own destiny.”

But make no mistake: Danny Glassmire loves the countryside. He has deep respect for the pure character of rural byways, like the one in the middle of his current prospect. “It’s like the most luscious ring of Saturn, Route 6 is,” he said. His last big job was delivering pizzas in Pittsburgh, where he landed after graduating from the English department at Ohio State in 2004. He thought he would finish his novel there, but life in the city was too distracting. “It’s like out of American Beauty, where the guy says, ‘Yeah, I remember that summer where all I did was flip hamburgers and get laid.’ It’s just one of those things.”

“I always do the There Will Be Blood impression,” said Glassmire. I’m like, ‘You have your milkshake, and over here, this is my milkshake, and my straw goes into your milkshake and sucks it up.’ ”

His father, a lawyer, got him into the prospecting game. It suits him better, but he’s still not done with his novel. The day before I arrived in Binghamton, Glassmire had put 300 miles on his car visiting his landowners, then left it parked outside a bar. He taxied home. “I’m getting a lot better at not drinking and driving—I’m not impeccable at it, though,” he said. Sometime in the middle of the night, he swigged a glass of water, which turned out to be where he had put his contacts to soak. That left him with just one lens to his name, so he spent the morning wandering around Binghamton with one eye closed, trying to find his car.

He represents Cabot Oil & Gas, an independent exploration firm from Houston, making $200 a day, plus expenses and $35 for food. With experience, he expects his rates will steadily increase, but he’ll never be paid a commission. That’s not typically the way of the industry. A good landman is motivated more by a certain lone competitive pursuit, man against map.

“It’s sort of like, in a way, territorial military theory. It’s like deterrence and movement,” he told me as he pointed out what he called the “gorgeous rainbow” on his map of Susquehanna County. More than half the parcels were colored in: yellow for Cabot, purple for Chesapeake Energy, blue for Turm Oil. By far, Cabot is the dominant force here, and Glassmire plays the map like a video game, concentrating on putting yellow on parcels that connect to other Cabot lands while holding the competition to quarantined pockets. “What I tell people, and it’s true, is that Cabot has 26 or 27 wells in already and Chesapeake has one. The only other one that’s impressive, but it’s not really impressive, is Turm Oil, which has eleven. That’s it. The yellow is Cabot. You can see this map speaks for itself. This prospect is Cabot’s.”

His specific responsibility is tax map 161 and tax map 142. Though he has been working these particular maps for only fourteen days, he has already signed four leases, for a total of 50 acres. He was proud of this accomplishment, though he acknowledged the prospect was selling itself in an area where employment is low and the typical home is a trailer or vinyl-clad prefab on about fifteen acres. Besides the signing bonus, Cabot is paying 16 percent royalties. Many residents eagerly sign without a lawyer; those who don’t are holding out for a better offer. He hasn’t found a single person who is anti-gas.

He closed one eye to regard the map. Strategically, he knows what he has to do next. The large block of yellow on the northernmost reaches of map 161 is separated from the large yellow block to the south by two lots of unleased property. They are arranged in such a way that he only needs one of them in order to make his prospect contiguous, which is essential for when the pipeline comes. The smaller piece is an L-shaped parcel belonging to someone named Rozell.

“I can tell you she’s an 85-year-old widow,” he said. “For some reason, I haven’t talked to her yet.” The bigger prize would be her next-door neighbor, let’s call him Robert Porter. Glassmire hasn’t called him, either. The Porter tract is 50 acres, one of the largest in 161, but Glassmire knows he’s got other property as well.

Leasing Porter would be a coup. With one negotiation, the rest of map 161 would fall into Cabot’s column. But Porter isn’t an easy mark. Other Cabot landmen have talked to him. Glassmire referred to takeoff notes they had entered into Porter’s file. He appeared to be a quarryman with offices in Scranton. Glassmire contemplated showing up at the office unannounced, but hadn’t settled on his strategy.

“For one thing, I have in my notes that Porter is asking for $3,000. Which theoretically means it doesn’t matter if I do go to him, because I can’t do $3,000. So I have to create my own sort of portal on that. Get my own—” He rolled his eyes toward the ceiling. “Generate my own horse’s mouth. See what he says to me.”

He crashed onto his bed, landing on his copies of Henry Miller’s Sexus, Faulkner’s The Sound and the Fury, Harry Mulisch’s The Discovery of Heaven, and Saramago’s Blindness. He pulled the map over him like a sheet. “That’s a guy who wants a lot of money, Robert Porter. Like, if the common good is this much, he deserves a percentage higher. He’s like a Real Important Quarryman. The Beatles used to be called the Quarrymen, did you know that? Do you think the Beatles were really from Susquehanna County instead of Liverpool?” He cracked himself up.

Natural gas is the white meat of fossil fuels. It burns considerably cleaner than coal, gasoline, and oil, and it has the advantage of being independent of the Middle East. Plus it’s relatively cheap. Increasingly, cars are being outfitted to burn it, at a third the price of gasoline. To meet the growing demand, a 182-mile-long, 30-inch-diameter Millennium Pipeline is being built across the Southern Tier of the state. It will connect to New York City by November. Much of the expected Marcellus Shale lode will come directly to the city.

But natural gas is no solution to global warming. It still contributes greenhouse gases. Worse, the process of extracting natural gas turns out to pose serious environmental risks. Of immediate concern is the drilling process. Some of the impact is temporary, as Glassmire said. Large crews work around the clock under a canopy of lamps that can make country lanes look more like a scene from Close Encounters of the Third Kind. And the drilling is noisy, says Bruce Baizel, an attorney for the Oil & Gas Accountability Project, a Colorado nonprofit. “Drilling rigs run up to 100 decibels,” he says. “That’s higher than a jet plane.”

But the greater concern is the horizontal hydraulic fracturing process—known as “fracing”—which rattles the ground like earthquakes. Out West, where fracing began in 2003, neighbors complained that the process spoiled their drinking-water wells and damaged their foundations. The water for blasting open the shale and freeing the gas is treated with chemicals, to help break up the stone, and mixed with sand, to hold open the newly created fissures. Exactly which chemicals are used is not publicly known. The recipe was pioneered by Halliburton. The company considers the formula to be a trade secret and guards it like Kentucky Fried Chicken guards its batter recipe. One large independent study of fraced wells in the West, by the environmental scientist Theo Colborn, identified over 400 chemical toxins in contaminated groundwater and soil, including the carcinogens ethylbenzene, chromium, and arsenic.

No prosecutions were brought. I was astonished to learn that the Energy Policy Act of 2005, passed by Congress in part to reduce dependence on foreign energy, specifically exempts oil and gas companies from major environmental-protection laws. These include the Safe Drinking Water Act and the Clean Water Act.

I repeated all this to Glassmire, but he had trouble seeing gas companies as bad guys. “The soil is maintained, it is reestablished, life is preserved,” Glassmire said. “I can’t worry about tremors, I can’t worry about the blasts and the trucks—I don’t know, but don’t ask me to worry about that.” He put on his self-mocking There Will Be Blood voice again. “You know I wish everybody well, but on the other hand I really don’t care.”

Environmental groups have called for a ban on gas collection until these matters are resolved. Three New York townships have adopted formal moratoria, joined by a vocal group of landowners who find the very idea of gas drilling horrifying. Some are gearing up to battle Big Gas. “I hope to God we can stop this,” says the journalist Jan Goodwin. She bought her weekend home not far from Callicoon in 1982 and was recently planning to leave Manhattan altogether for her wooded retreat. Now those plans are on hold. “We didn’t know about this till January, but the landmen were in there stealthily meeting in bars and cafés with farmers and waving around very large checks. They have no options, and they see this as manna from heaven.”

But others aren’t hungry for the warfare. The artist Christy Rupp, who lives in Bovina, is a veteran of the wind-turbine wars. “I’m not sure we have the energy to do it again,” she said recently as she left a landowners meeting in Delhi, the Delaware County seat. “I think I’m screwed.” Inside, most of the 250 in attendance appeared to welcome the new economic opportunity. In their notebooks, people calculated their potential windfalls. An older woman in the audience wanted to know how she could fast-track her payments. “How can I get in touch with one of these landmen?” she called to the stage. “I haven’t got much time left.”

At a similar meeting in Liberty, I asked Paul Zimmerman, a local councilman from Eldred, New York, if the gas might ignite a deeper division between locals and weekenders. “It already has,” he answered. But he believed that weekenders misunderstand what’s at stake. Mining the gas is an act of national urgency, in his view, one that will help break dependence on foreign energy. “It’s not us against them, the weekenders,” he said, “it’s us against Big Oil.”

Lifelong Eldred resident Dave Jones and his wife, Patrice, have already sold mining rights to their 50-acre home. They’re confident the system will take care of everything and prevent disasters. “If a gas company comes up around Broome County, and if they make an absolute mess out of that, the word is going to get out,” Jones told me. Not coincidentally, state regulators agree. “These things are relatively low-impact,” says Brad Field, director of the New York State Department of Environmental Conservation’s Mineral Resources Division. “There is a good regulatory program in place.”

Scores of drill pads will probably erupt in the Catskills in another year, Glassmire predicted. “The prospect will change us both,” he told me.

It does seem that Big Gas is unstoppable. The money’s too good, and fossil fuels have federal law driving their momentum. Even if I want nothing to do with drilling, I could still see my land pockmarked. Under law, if 60 percent of my neighbors sign up, I can be forced to lease my land through a provision called “compulsory integration.” Scores of drill pads will probably erupt in the Catskills in another year, Glassmire predicted. “The prospect will change us both,” he told me. “It’s like you and me are walking, and there’s just two footprints in the shale.”

The morning after my arrival, Glassmire was up at dawn to collect his e-mail and communicate with his office, which is based in central Pennsylvania. At 8:30, he called and invited me to his room, saying, “If you want a sense of a landman’s life, now’s the time.” He was in an oxford-cloth shirt, blue dress slacks, and black leather dress shoes when I arrived. Pages of documents were piled in his printer tray.

“The news is bad,” he told me right off, stroking his patchy scalp. “The widow Rozell is signed.” According to a lease register forwarded to him overnight, another Cabot landman had brought her in. Technically, this wasn’t poaching. Rozell’s driveway was actually located just across the boundary in tax map 160, making her a legitimate kill. But it’s put Glassmire out of sorts. “It’s not that I mind,” he said glumly. He took out a yellow marker and filled in the tract, joining north with south and making a clear path for the pipeline.

As a result of this development, the Porter tract may have taken on less significance to Cabot but more to Glassmire. He pinched his contact into his right eye to reread the takeoffs out loud. “ ‘Brothers own various tracts.’ You’ll probably have a bunch of people who need to sign, so it’s going to take forever regardless. ‘Met for breakfast, initially interested. Now refusing offer.’ Who knows when these occasions were. ‘Still dragging feet.’ Very poetic way of putting it.”

He dialed a number he found on WhitePages.com. The person answering the phone said Robert Porter wasn’t available but connected Glassmire to his brother, who talked his ear off. When he finally folded his phone, Glassmire’s mood had lifted. According to the brother, the Porter family controls 1,700 acres in the area under various corporate umbrellas. Most of their property is outside of Glassmire’s maps, but landman etiquette would allow him to sign it all because some falls on his map. And the Porter family appeared ready.

Through the short span of his career, Glassmire has signed 8,000 acres in all. Adding the Porter properties would increase his tally by nearly 20 percent. He bent to tie his shoe. “I might take them all—as long as I get the ones I’m after.”

Through the afternoon, I accompanied him as he visited his other contacts. Our first stop was on map 142: the Lavigne household, a raised ranch next to a vegetable patch on 12.16 acres, owned by retired Long Island transplants. They had wanted to add a few amendments to the lease affecting the way royalties are paid out, and Glassmire secured permission to accept a few of them. Pleased, the Lavignes read over the contract one last time, with big plans for their $30,000 signing bonus. Glassmire fiddled with a jar on the kitchen table. “Wow, is this honey in there?” he interrupted.

“Buckwheat honey.”

“Wow, that’s serious. If we had some of that, we’d be roaming through the woods picking dandelions.” He snorted. “Just sign over your name, Mr. Lavigne. Any place you see your name.”

On the way out the door, Glassmire asked the Lavignes to keep their amendments a secret. “I’m going to ask a favor. I know you don’t tell other people your business. This is a smart thing to ask for, it’s basically fine. But I ask you to not tell your neighbors about this. I mean, we’ll give it to them if they ask, but only if they ask.”

In the car, he rejoiced in his own momentum. He put My Morning Jacket on the satellite radio. “This is my fifth lease. From the 11th to today, five leases.” This was in stark contrast to his experience in my valley, he said. He admitted he worked there for six weeks without filing one signature. “It’s supposedly the hardest prospect for a landman, Delaware,” he said. Instead of people like Lavigne, he was chasing names like Kelsey Grammer, Harrison Ford, and Manny Ramirez, the Red Sox slugger. “You’ve got landowners who live in Malibu. They’re extremely unincentivized.”

Despite traveling around the region to the primary homes of Delaware landowners, he still failed to execute a lease, he said.

I asked him where he’d traveled, and he said, “I was at your apartment.”

I was momentarily stunned. “My apartment in New York City?”

“East-something,” he nodded. The Caesars’ “Jerk It Out” came on the radio. “Thirteenth Street? Eleventh Street? Something like that. You weren’t there either time—I went twice.”

I felt utterly violated by this intrusion. Who besides a Witness for Jehovah buzzes a doorbell uninvited? I pictured him standing in my lobby, stroking down to my name on the buzzer box; I pictured him picturing me as a pawn in his territorial military theory.

But I also felt somehow bonded to him as a result. His having stalked me to a forgotten street in the East Village was really not too different from my having followed him to an unnamed motel in Binghamton. We were drawn together by the Marcellus Shale to see how far this prospect could take us. That night, we toasted the big shale stone with Jack on the rocks. “We watched the prospect shiver and molecularize a little today,” Glassmire said, sipping. “A night to celebrate.”

I had to admit I was no closer to knowing what to do the next time a landman offered us a lease. It’s just not possible to turn away all those millions, I told him. But it seems just as impossible to take those risks with the environment. “My one hope is that the city will rule out drilling in the watershed—that would take the whole matter out of our hands,” I said. It was the chicken’s route. Half the state’s population relies on the watershed for its drinking water—1.2 billion unfiltered gallons reach the city every day, nearly all of it propelled only by gravity. It is the largest unfiltered surface-supply water system in the U.S. It seems inconceivable that anybody will allow drill bits and mystery fracing chemicals to pass through the aquifer in the hunt for gas. The environmental groups Riverkeeper and Catskill Mountainkeeper have demanded an all-out ban above the city’s watershed. At a special hearing on the issue two weeks ago called by City Councilman James Gennaro, Speaker Christine Quinn expressed alarm. “We can’t allow drilling to proceed until we know what the consequences will be,” she said. “We should not move forward at this time.”

But it’s unclear whether the city’s Department of Environmental Protection has the authority to stop the drilling, much less the inclination. A few weeks ago, a letter was leaked from the DEP that proposed a no-drill zone. But the limits were much smaller than some had hoped. Rather than ban drilling in the entire watershed, the DEP letter suggested a moratorium within a mile of any of the nineteen reservoirs in the system. Unfortunately for me, or fortunately, we live about seven miles from the Pepacton Reservoir.

I looked Glassmire in the eye. “What would you do? Would you take the money?”

“Oh,” he said. The question left him momentarily speechless. “I’d want to see some producing wells. I’d want to see the maturation of the addendums, stuff like that. I’d wait till the fall.” He thought some more. “I’d be kind of closing onto doing it, sort of biding my time.”

Over the following days, Glassmire scooped up one lease after another. He even made progress on Robert Porter and his brother. They talked on the phone and met a couple of times. “For all intents and purposes, you can call that the Porter Pocket if you wanted to,” Glassmire told him. “You’re pretty much the biggest deal there is.” But the Porter brothers ran hot and cold, so Glassmire’s mood surged and crashed. Late one afternoon, he left an update on my voice mail. “I know I’m bothering you with these messages, these warped diatribes, these negotiated pitfalls,” he said. “But the thing is, these Porters are lingering in front of me.” He suspected another landman was making this deal even more difficult, but he wasn’t sure. And he wasn’t giving up. “It’s hard to tell exactly what sort of unnerving thing is going to happen. I’m positive about it. I wish it would kind of go to the concrete. But it’s more exciting in some ways to be in this frenzy.”