Dennis Malvasi was the kind of kid everyone else wanted to be—the funny one, the street-smart one, the handsome one with a natural swagger. The Brooklyn neighborhood he grew up in was one of the worst slums in the city; East New York in the mid-sixties was a gangland, perpetually on the brink of a race riot. But Dennis always seemed above it all, despite being worse off than most. He had eleven brothers and sisters, with three fathers between them. His mother was so poor she sent him for a time to an orphanage upstate. Maybe it was knowing so many unwanted children that explains what happened later.

Dennis entered the Vietnam War just after the Tet Offensive. He was 17 but so eager to enlist that he found a stranger in the street to sign his parental-consent form. He served one tour as a field radio operator, drawing VC fire on a number of occasions, then turned around and re-upped for a second. As a soldier, “I felt really alive, really wanted,” is how Dennis put it. Life at home was harder. He was arrested for being in a street fight—“hanging around,” he’d later say, “with some very dangerous people.” He tried to become an actor, joining an Off–Off Broadway troupe on the Lower East Side, even winning some acclaim. But in 1975, he got stopped and frisked by a police officer on a subway platform. He was carrying a .25-caliber pistol. It was his second felony. He was sent upstate to prison for two years.

Dennis couldn’t get over the idea that he was behind bars while draft evaders received clemency. His anguished letters from jail were dated with the years he served in Vietnam, as if to will himself back in time. Some time after he got out, he became secretive—taking messages from a beeper, having his mail delivered to bars, getting jobs and a driver’s license under assumed names. He missed being in action and got licensed as a pyrotechnics expert to work with explosives. Then he started spending time with a group called Our Lady of the Roses, a Catholic fringe group that raged on about the evils of Vatican II and the sinfulness of modern life. The foulest of sacrileges, they believed, was abortion.

Dennis wasn’t a churchgoing Catholic, but he’d never believed in abortion. “Here’s the truth. Look. This is a life,” he once said, pointing to a picture of a fetus in a training book for paramedics. Now he complained to one friend about how he’d defended his country and was called a baby-killer while others were murdering the unborn with impunity.

On December 10, 1985, a small pipe bomb ignited inside a vacant men’s room at the Manhattan Women’s Medical Center on East 23rd Street. Eleven months later, another homemade explosive, this one with a half-stick of dynamite, blew a hole through the wall of the Eastern Women’s Center on 30th Street. Two weeks after that, police found an unexploded bomb with three sticks of dynamite inside a sofa at a clinic on Queens Boulevard. Finally, on December 14, 1986, the bomb squad burst into the smoke-filled Second Avenue headquarters of Planned Parenthood to find a carpet fire started by a small incendiary device, not far from a larger bomb with fifteen sticks of dynamite, enough to destroy the front of the building had it not been defused in time. The attack had the hallmarks of a highly motivated professional: blasting caps, timers, batteries, and a Catholic medal of St. Benedict. Dennis Malvasi was New York City’s first abortion-clinic bomber.

Joseph had come to Brooklyn with his family in the sixties when he was 14 years old. His parents were shtetl Jews who had stayed in Poland during the war, fighting the Nazis, only to leave in 1960 when some kids went after Joseph with a straight razor, claiming that his parents had killed Christ. His family found a tenement in the only slightly less dangerous neighborhood of East New York. His father worked as a leather cutter, his mother as a seamstress. Joseph was prone to fainting spells and panic attacks, and had to learn to speak English without a lisp. Even his friends called him the Trembler. He tried playing the clown but was too cloying and needy. “I was the water boy,” Joseph remembers. “I was in the background.”

Joseph, whose identity has been protected here for reasons that will become clear, can’t remember when he first met Dennis. It was 1964 or ’65, out on the street, playing skelly or picking up girls. He remembers Dennis as very friendly and very poor. “We hung out, but it was, ‘Hi, how’re you doing?’ We didn’t develop a closeness.” Within a few years, Dennis had enlisted and Joseph had been drafted, and the two lost touch. As a noncitizen, Joseph served Stateside, then spent the seventies leading a small, dead-end sort of life. He was a process server for the courts, a collection agent, a driver, and, finally, a counselor to veterans for the State Department of Labor. It was there, in 1985, that Joseph got a call from a friend, asking if he would look after a down-on-his-luck Vietnam veteran from the old neighborhood named Dennis Malvasi.

They met again on a sunny afternoon at a pretzel stand outside Saint Patrick’s Cathedral. Within minutes they found they knew a lot of the same people, and Joseph was enthralled. Here was someone from the old days who’d gone on to become a war hero, someone who made him feel like a big shot just by knowing him. “It was the same old Dennis,” Joseph remembers. “Easygoing: ‘Everything’s going to be all right.’ A sweetheart. He stood up for this country and the war. I looked up to him—respected him for doing it.”

Dennis spent the early weeks of 1987 hiding from the police—and laughing over the phone (though not with Joseph) about what a bad job the cops were doing finding him. The manhunt might have gone on longer if Cardinal O’Connor hadn’t appeared on the news in late February, delivering a plea for Dennis, who was publicly identified as the main suspect, to give himself up. The next day, Dennis, wearing an eyepatch and sunglasses, walked unnoticed into the Church Street headquarters of the Bureau of Alcohol, Tobacco, and Firearms. “It’s hard to turn down the cardinal,” he said. Then he asked for a lawyer.

Dennis pleaded guilty to two of the attacks, and the other two charges were dropped; largely because no one had been seriously hurt, he was sentenced to just seven years. Behind bars, he grew more defiant. “History will show that abortion in New York State was nothing more than the dissipation of the black and Puerto Rican populace,” Dennis said in his one jailhouse interview.

One day in 1992, Joseph got a call from someone he and Dennis both knew. The two men hadn’t been in touch since the conviction. “Dennis is coming out,” their friend said. “Take him in.”

They made a point of never talking about what Dennis had done. “We made a pact,” Joseph remembers. “I said, ‘Look, don’t drag me into your world. What you have done in the past, it’s history.’ He promised me, ‘Yes,’ and that’s it. I took his word for it. But Dennis had two different lives.”

So, eventually, would Joseph.

Joseph remembers the first few months after Dennis got out as an idyll. They lived near each other in Brooklyn again, goofing off like they were kids. Joseph bought Dennis a used Oldsmobile, co-signed for his credit card, helped him find odd jobs. Taking care of Dennis made Joseph feel like the important one. They chased women, too—until one day Dennis dropped by Joseph’s place with a woman dressed in a simple long skirt, like a Mennonite. She seemed about 30, a decade younger than Dennis, and was plain-looking, with long dark hair and dark skin, and green eyes.

“This is Rose,” Dennis said. “She’s gonna be my wife.” Rose was the nickname of Loretta Marra.

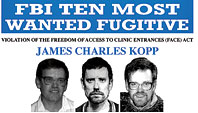

Loretta was the closest thing the radical pro-life movement had to Joan of Arc: a compelling, innocent-seeming young woman speaking out against the evils of abortion. She was born into the movement. Her father was a Fordham philosophy professor named William Marra who ran as a third-party right-to-life candidate for president in 1988. From an early age, she began speaking at demonstrations and chaining herself to other protesters outside clinics in America and Europe. Her good friend and perhaps closest spiritual ally in the abortion war was a man named James Charles Kopp.

A biology graduate student from Pasadena, California, who abandoned his career to devote his life to saving the unborn, Kopp had been a regular at clinic protests throughout the eighties. He went to work for Randall Terry, who founded Operation Rescue, and crossed paths with Michael Bray, a central figure in the Army of God. His first major contribution to the cause was the invention of handmade, Kryptonite-lock-style shackles that could block clinic entrances for hours. He met Loretta’s father at a protest in Florida in the summer of 1986, when she was just 23. Friends said Kopp and Loretta were instant soul mates, almost finishing each other’s thoughts. Some say Kopp was in love with her.

Loretta and Dennis were married in 1994. Two years later, Loretta delivered a baby boy named Louis. A second son—James—was born in April 1999. The couple lived secretly, Joseph says, using fake driver’s licenses, dodging Dennis’s probation officer, keeping anyone from seeing the inside of their apartment. According to Joseph, Loretta once persuaded Dennis to quit a job after she noticed that one of the company’s contracts was with a hospital that performed abortions. Joseph didn’t know until years later that their wedding had never been recorded with the state and that Loretta had delivered both her boys in Canada. And he didn’t know that even after Loretta and Dennis got married, Loretta had kept in touch with her friend James Kopp.

Sometime in 1998, Dennis came to Joseph’s apartment carrying a large sack. Joseph looked inside. It was a rifle.

“What the fuck?! Are you for real?”

“I’ve gotta store it,” Dennis said, “for a friend.”

The nation’s most notorious abortion-related murder had taken patience. James Kopp visited the woods behind the house on the outskirts of Buffalo for days—wrapping his Russian-made SKS in vinyl and stowing it in a tube he’d planted in the ground, then covering the tube with leaves until he came back, waiting for the right moment. Finally, at 9:55 p.m. on Friday, October 23, 1998, Kopp got the shot he wanted. The abortion doctor was standing in the kitchen, microwaving a bowl of soup. Kopp pulled the trigger. The bullet shattered a window and hit the doctor in the back.

“I think I’ve been shot,” Barnett Slepian said.

“Don’t be ridiculous,” said his wife, Lynne.

He bled to death before he could get to the hospital.

Slepian’s death instantly galvanized the abortion debate: Pro-choice supporters cried out for justice; militant pro-life advocates proclaimed that justice had been done. Bill Clinton called the killing a “tragic and brutal act.” The Justice Department launched an international manhunt for the sniper. But Kopp had a carefully thought-out getaway plan. He dyed his hair blond to match a fake driver’s license, and a friend drove him to the Mexican border. Within weeks, he flew to London undetected; from there he’d move on to Ireland. But Kopp had one stroke of bad luck. A woman who lived near the Slepians told the police about a man she’d seen while jogging who had seemed out of place. She’d even written down his car’s license-plate number.

On November 4, a material-witness warrant was issued for James Kopp, with a $500,000 reward offered for information; by the time Kopp was indicted, the reward had been raised to $1 million. FBI agents raced to search all the places he had lived over the years and to interview friends. Near the top of their list was Loretta Marra. They found her pager number in the phone records of another friend of Kopp’s but still couldn’t locate her. They went to her father’s funeral in December, but she didn’t show up. Their best move, they decided, was to somehow get to Dennis Malvasi.

In the spring of 1999, Joseph says he was in the parking lot of a shopping center on Ralph Avenue when a van rolled up next to him and stopped. The van door slid open.

“We want to talk to you.”

“Forget it,” he said, and kept walking.

Joseph knew Dennis was still on parole. He figured this must be about him. So he told him about the van a few days later. “I was followed,” he said. “You better watch it.” Dennis smiled cryptically and thanked him.

A few weeks passed, then it happened again—this time an SUV pulled up beside Joseph while he was parking his car.

“Can we talk now? It doesn’t have to be here. We don’t expect you to trust us.”

“No,” Joseph said. “I don’t want to get involved”—though he had no idea what Dennis might have done.

In mid-September, Joseph was hanging out in Marine Park, making conversation with a plainclothes detective he knew named Julio.

“There was a killing in Buffalo,” Julio said.

“Yeah?” said Joseph.

Julio told Joseph that the victim had been an abortion doctor.

Joseph’s mind flooded. Dennis.

Days later, on September 27, 1999, Joseph found himself sitting in the back of an SUV with tinted windows parked at a Toys ’R’ Us near the Kings Plaza mall on Flatbush Avenue. Julio was there, to make him feel comfortable. And in the driver’s seat was a man in a dark suit. The man was smiling. “How,” asked the man, “would you like to have $1 million in your pocket?”

A few days later, face-to-face with FBI agents in an airless downtown hotel room, Joseph panicked. He started making demands, insisting that no one call him by his real name. He even made up a pseudonym on the fly: Jack, from a framed poster he saw on the wall, Steele, from Remington Steele. He still wasn’t ready to cooperate, but the agents kept pursuing him, asking to meet again and again, and in October, a new agent called. “Would you give me a try?” asked Michael Osborn of the New York office. Osborn told Joseph that all he wanted to know was what Loretta and Dennis knew about the case. He was respectful; he even called him Jack Steele.

Joseph was running out of reasons to say no. He knew they’d never stop asking. Maybe, he told himself, there was an angle here: If Dennis was clean, no harm done; if Dennis did happen to know who did this, he would help solve a murder and go home a millionaire.

So he said yes.

Joseph insists his decision wasn’t about abortion. It was about murder. “Pro-life? I got no problem with that. But murdering someone? I got a problem with that regardless who they are.”

Then there was the money—or as Joseph calls it, “the incentive.”

“Want me to lie to you and tell you no?” Joseph says. “I’d be lying to myself.”

The bureau wanted to bug everything—Dennis’s place on Chestnut Street, Joseph’s car—so they could listen as Joseph tried to get Dennis and Loretta to reveal where Kopp was. But until they could get warrants, Joseph would be their eyes and ears. The agents provided Joseph with cash for entertaining Dennis and Loretta. He was already buying them meals almost every day; now the FBI was picking up the tab. Joseph would tag along with Dennis to trash cans where he got rid of reams of paper so the FBI could search through them once Joseph tipped them off. Later, Osborn suggested that Joseph give Dennis a bunch of prepaid phone cards that the FBI could trace. In time, the FBI knew about every call Dennis and Loretta made or received. Joseph once sat with Dennis and Loretta at his place as they watched a 60 Minutes segment about the hunt for Kopp, waiting for them to give something up. They said nothing the agents could use.

About a month into his surveillance, the three of them were in Dennis’s car, heading home from a Chinese buffet in Canarsie. Loretta’s cell rang. She picked it up and gasped.

“It’s him! It’s him!”

“Pull over,” Dennis said.

Joseph might have guessed they were talking about Kopp, but he wasn’t sure. He tried to act uninterested. “Dennis, do me a favor, man. Just drop me off.” That night, he called Michael Osborn and told him what had happened. All he got were questions—what did Loretta say? Who was she talking to? They needed more.

“How,” asked the FBI agent, “would you like to have $1 million?”

By the end of 1999, Kopp had made his way from London to Dublin, calling himself Timothy Guttler, walking the streets, even hanging out in well-traveled spots like Bewleys coffee shop. The following July, he took the name Sean O’Briain, a name he’d seen on a local tombstone. Kopp wanted eventually to return to Canada or America—perhaps just to be around the people he loved, perhaps to come out of what he called “retirement.” Throughout his exile, he wrote letters—at times lighthearted and jokey, at times sentimental—to his friends Dennis Malvasi and Loretta Marra at 385 Chestnut Street in Brooklyn.

Joseph, meanwhile, spent the next year hinting to Dennis and Loretta that he wanted to join their cause. Joseph would tell Michael Osborn he was going on car trips with Dennis and Loretta, and the FBI would loan him cars with bugs; he’d tell Dennis and Loretta his own car was in the shop. According to FBI transcripts from Jon Wells’s book about the Kopp case, Sniper, Joseph (referred to in the book as a “confidential source”) and Loretta were talking on one car trip about gumming the locks of clinic entrances with glue—a tactic used to stop abortions, if only for a few hours.

Joseph brought up the Slepian murder.

“You think the shooter was trying to kill him?” he asked.

“You’re always out there to maim,” she said.

“What’s Jim’s opinion on that?” he asked—slipping in a mention of Kopp’s name.

“I know he feels bad for Slepian’s children,” she said. “But he knows Slepian was not an innocent person, either. He was, morally, a guilty person.”

Joseph couldn’t think of a way to ask Loretta where Kopp was hiding. Instead, he brought up Dennis’s clinic bombings. That was when Loretta told Joseph that she thought Dennis never should have surrendered to the cardinal. “In my opinion, Dennis had an obligation not to obey him,” Loretta said. “O’Connor’s request was a sinful command.”

On another trip, Joseph remembers asking Loretta, “Would you really have the fortitude to kill a human being?”

“I think I’d be capable of killing,” she said, “for God and a higher good.”

After Joseph and Loretta came home, Osborn pushed Joseph to go inside Dennis and Loretta’s apartment; they’d always made excuses whenever Joseph tried to enter. Joseph went on a shopping spree and came over on the pretext of delivering presents. “They had a little room, nothing much,” he remembers. “They slept on the freakin’ floor.” When Loretta stepped out to a bodega, Joseph started to play with little Louis. Joseph pointed to a picture on a shelf of James Kopp with a cross on it.

“Who’s this guy?” Joseph asked.

“Oh, that’s Uncle Jim,” said Louis.

“You saw him?”

“Yeah.”

“Where?”

“In our old house,” Joseph remembers the boy saying. He meant the place his parents had moved from on Linden Boulevard. “He came up to see us once.”

On the Friday night after one car trip, Loretta picked up Joseph at his apartment for his first clinic action. Joseph was married now, and he told his wife, Rachel, that he was going out to play cards. When he opened Loretta’s car door, he saw she was wearing fatigues. She’d gone to three different stores to buy toothpicks, glue, and a dark cap for Joseph. They drove across Brooklyn to a doctor’s office on Church Avenue that they had cased during the day. Loretta parked. In Joseph’s hand was a toothpick dripping with glue. He opened the car door, and walked out into the rain.

When he got to the clinic, Joseph picked up his cell phone and called Osborn.

“Michael,” said Joseph, “I have a toothpick. I have Krazy Glue. I’m gluing it.”

“You’re not gonna glue it,” the agent said.

“Michael, I don’t know what I’m gonna do.”

“You’re not gluing it. You’re breaking the law.”

Joseph laughed. “Come on!” he said. “A little won’t hurt.”

A pause. Then Joseph reassured him.

“Michael, I’m dropping the glue.”

Some glue dripped on Joseph’s fanny pack. A happy accident; now he’d have something to show Loretta. “Look at this!” he said, back in the car. “It’s all over me!”

Loretta couldn’t contain herself. She called Dennis. “Dennis, we did it, we did it!” All the way home and through the next day, it was all she could talk about.

Kopp started making plans to leave Ireland toward the end of 2000, perhaps for Germany. He was issued an Irish passport under the name John O’Brien in November, and applied for a driver’s license under the name Daniel Joseph O’Sullivan in December. But to travel, Kopp needed money, and Dennis and Loretta happened on a way to raise some.

In January 2001, Dennis and Loretta drove south on the New Jersey Turnpike to attend the annual White Rose Banquet in Bowie, Maryland—the ultimate radical pro-life trade show. Created by Army of God’s Michael Bray to mark the anniversary of Roe v. Wade, the White Rose featured speakers paying tribute to people jailed for attacking abortion clinics. (The name White Rose was borrowed from a group of German resisters to the Nazis.) Dennis, an A-list celebrity in this circle ever since the New York clinic bombings, agreed to be one of that year’s honorees. To raise money, he would auction off a wristwatch he’d used as a timing device in his attacks.

Dennis and Loretta invited Joseph to come with them on the trip. Milling around the banquet room, Joseph got his first look at the stars of the pro-life movement. There was Donald Spitz from Army of God, who called Barnett Slepian a “serial murderer” and his assassin a “hero.” There was Chuck Spingola, who wrote, “I believe James Kopp was serving Jesus the righteous, if and when he killed the baby-butcher Slepian, ending his abhorrent and satanic lust for innocent blood.” And there was the Reverend Matt Trewhella, founder of Missionaries to the Pre-Born, who once said, “This Christmas, I want you to do the most loving thing. I want you to buy each of your children an SKS rifle and 500 rounds of ammunition.” Joseph remembers watching the banquet room fill up with women in long skirts, men in ties and jackets, and children—“little blonde girls, 11, 12 years old. You could hear the kids preaching hate against the animals who killed babies.”

Then came the speeches. “They were preaching hate to faggots,” Joseph says. Later, Bray and Spitz brought up the Jews—Dennis shot Joseph a look.

“Don’t say a fucking word,” he said.

Joseph was silent.

Loretta never set foot inside the hall. There was media there, so she stayed away, afraid of being recognized. She did, however, help write Dennis’s keynote speech in the car on the way down. “One favorite [saying] is, ‘Violence never solves anything,’ ” he told the crowd. “Of course it does. It solves all kinds of problems. And just men have used it as a tool throughout history.” Dennis ended by saluting “the noble work of supporting your local baby-defender, from lock-gluers to bombers … arsonists, and snipers. Your help makes all the difference in the world—to the babies themselves.”

On the way home, Joseph decided to push a little harder. He talked with Dennis about what it might take to meet the man who killed Barnett Slepian.

Dennis looked at Joseph.

“Maybe,” Dennis said. For $4,000 or $5,000, he suggested, Joseph could have a picture taken with him.

“How about $10,000?” said Joseph.

“Maybe you’ll have a dinner with him.”

“If you need the money that bad,” Joseph said, “how about we go to Atlantic City? You know how good I am. I gamble, I give you the money.”

On February 3, Dennis and Loretta and Joseph and Rachel drove to the Trump Taj Mahal. The FBI bugged Joseph’s van for the trip—and even paid for the hotel rooms. Listening in on the car ride, the FBI learned that Loretta used a Yahoo! account to communicate with Kopp. At the Taj, Rachel went shopping, Dennis stayed upstairs with the boys, and Joseph and Loretta went to the casino to gamble.

After a short time, Loretta left the table to see Luciano Pavarotti perform at the Taj’s theater. Loretta had given Joseph her things to hang on to. For the next two hours, Joseph was alone with Loretta Marra’s wallet. Joseph rifled through everything, searching for addresses, phone numbers, anything that could lead to Kopp. His heart pounding, he called Michael Osborn from a pay phone. To make the search seem legal, he said the wallet had fallen to the ground accidentally.

“I read every single note,” Joseph says, “and one of the numbers was in Ireland. It was James Kopp’s phone number in Ireland.”

“Help me, help me!” Dennis was calling. “The FBI’s all over! They’re on the roofs!”

The FBI secured a warrant for the Yahoo! account, giving them a window into almost every communication between Kopp and his friends. They learned that Kopp was planning a return to the U.S. or Canada, and on March 21, they spotted a message from Kopp saying he was not in Germany but in Dinan, France. All they needed was an exact location to make the arrest. The FBI listened on bugs as Loretta and Dennis fretted about the logistics of bringing Jim Kopp home: money, phone calls, e-mails, wiring instructions, travel from Montreal into the States.

Dennis was unusually nervous. “You shouldn’t stay online so long,” he said. “Who else is using the account? And who established it? We have to get rid of the papers. I’ll wrap them in newspapers and throw them in the recycling boxes in the subway.”

On March 24, Kopp e-mailed Loretta three times about wiring arrangements: “Can’t get the $20 without the control number. Send the number on the e-mail account right way [sic] and then send $50 after that and $600 after that.” That same day, Loretta called Joseph. “I need you to come down here. Dennis is not here. I want to send some money.”

With her children in the back seat, Loretta and Joseph drove through a drizzling early-spring snow to a Western Union office near Jamaica Avenue. Loretta had everything written down. She handed him a sheet of paper with the address of a Western Union collection point in Dinan, France.

“Do me a favor,” she said. “I’m here with the kids. Why don’t you take this in?”

Joseph was shaking. Here was hard evidence linking Dennis and Loretta to Kopp—and a written record of where Kopp would have to be if he wanted to pick up his money. He could see now the whole thing would be over soon. He handed the forms to the clerk.

“Could you send $300?” And then, trying to sound nonchalant, “Could you make a copy, please, for me?”

Joseph folded over the copied papers a billion times and stuffed them into his sock, right under his foot. He put his boot back on and pushed his foot and almost cried out. It felt like a rock. Later, Joseph would call Osborn and read him the information. He thought he could hear the whole Earth stop on the other end of the line. He imagined Osborn was happy.

Back in the car, Loretta seemed to understand that Joseph had crossed a line of some sort. “We’re both into it,” she told him. “Anything that happens, we’re in it now together.”

five days later, on March 29, 2001, Joseph was supposed to meet with Dennis and Loretta for breakfast. As he was about to leave his apartment, his phone rang. It was Osborn.

“Where you going?”

“I’m going to meet Dennis.”

“Where is she?” Meaning Loretta.

“He says she’s at the laundromat,” said Joseph. “She’s doing laundry.”

“Under no condition go to see Dennis today.”

Joseph called another friend right away, taking him up on an offer he’d made to spend the day in Brighton Beach. The friend picked him up at about 10 a.m. On the way, the news radio station ticked off the headlines: James Kopp, the suspected abortion assassin, had been captured in Dinan, France.

Joseph’s phone rang. Dennis.

“Help me, help me! The FBI’s all over! They’re on the roofs!”

They’d already picked up Loretta on the way home from the laundromat. Now they were on their way in to get him.

Joseph hung up.

The cell rang again.

“Please help me! Help me! I got people—I got cops all over!”

Joseph hung up again.

It took two years of legal wrangling, but on March 18, 2003, James Kopp was convicted of the murder of Barnett Slepian. He was sentenced to 25 years to life in prison. In 2007, he was convicted for the federal offense of blocking access to an abortion clinic and received a life sentence without parole. Dennis and Loretta were jailed, too, for more than two years, as their cases slogged through the courts. At first they seemed likely to face up to ten years each for obstruction of justice and five other counts, but eventually they were just indicted for harboring a fugitive, carrying sentences of only a few years. The prosecutor tried to link Dennis more closely to the murder, claiming they had a witness who had spotted him in Barnett Slepian’s neighborhood less than two weeks after the killing, perhaps to retrieve the gun. But the judge declined to hear this witness and on August 21, 2003, sentenced Dennis and Loretta to time served. They were free.

On their way out of the courthouse, a reporter asked Dennis if he was still part of the anti-abortion movement. “I am an abolitionist,” Dennis said. “I have never been a member of the anti-abortion movement. So I don’t know what you’re talking about.”

Dennis’s close friend Abe Laufgas says that Dennis and Loretta are now living “somewhere around” Newark, in a slum not so different from the East New York of Dennis’s youth. They’re reunited with their boys (a sister of Loretta’s took care of them while they were in jail) and have a third child, a girl named Lydia. The family lives largely off the grid, says Laufgas—no cell phones, no real names. Dennis repairs computers—“nothing you’d call a steady job,” Laufgas says. Money is tight. “They won’t take welfare from the state, ’cause then the kids can’t be home-tutored, and then the state’s going to tell them what to do. They’re still revolutionaries, you know?”

They’re also still in touch with their friends from White Rose. “As a matter of fact, I was in touch with Loretta just a week ago,” Michael Bray of Army of God told me in June. They had been hashing out a theological matter. “I was working on a new catechism. It’s for children. Just a fresh look at what the Christian faith is now. And I had her review it for me. Because I know she’s sharp.”

Last year, Loretta attended a court appearance of Kopp’s and was spotted by a reporter. “My life will never be normal,” she snapped. “Not when this country is bathed in the blood of millions of children. All I can smell is the stench—the stench of the blood.”

James Kopp is now several years into his sentence at a federal prison in West Virginia. Not that long ago, he was asked why Loretta and Dennis named their second child James. “You’ll have to ask Loretta,” he said with a smile.

Joseph is 62 now—round but solid, balding and tan, almost always grinning and fidgeting. Since 2002, he’s been living with Rachel in a Spanish-modern villa in a well-manicured gated community in Florida, having collected most of the $1 million reward for information leading to Kopp’s capture. He isn’t in a witness-protection program—as an informant, not a witness, he was never offered that option—but he’s trying to live as if he were. He and Rachel aren’t listed in public phone or address records, and he makes ample use of caller I.D. Fearing reprisals by pro-life activists, he asked to change his name and his wife’s for this story.

When I visited Joseph earlier this year, he walked me through his place, showing off his five bedrooms, five flat-screens, a small pool, and the garden he tends during the day while Rachel works. Much of the time, he admits, he’s bored out of his mind. The only thing to do here is play golf. “I’ve never played golf in my life,” he says, laughing. “I’m from Brooklyn.”

He and Dennis haven’t spoken since that phone call, the day of Dennis’s arrest. But Dennis did try to reach out to him from prison. At his dining-room table, Joseph sifts through cartons of old papers and finds the letters—more than a dozen from Dennis, all in longhand. One early letter is long, scorching, accusatory: “You cannot imagine the stunning blow and crushing spirit we have undergone by all this suffering and betrayal,” Dennis wrote.

But months later, once a plea seemed likely for him and Loretta, Dennis’s tone grew a little warmer. “It’s taken me all this time to stop being mad at you,” Dennis wrote. “But actually if I were you I would have done the same thing proberly [sic], so I really can’t be mad at you anymore.”

The strangest letter came in March 2003, just after Kopp was convicted, but before Dennis and Loretta knew their own fate: “Congratulations! You deserve that money—all of it … Don’t let them screw you out of your money. I would be more than happy to testify on your behalf.” It was the last letter Dennis sent. Joseph would like to think that Dennis was trying to be nice—that he really wants the best for him. But Rachel thinks he was just trying to get into Joseph’s head.

Abe Laufgas says that he believes Dennis has forgiven Joseph now—at least somewhat. “He knows how Joseph was and how Joseph is, and he figured that the Feds put pressure on him. And Joseph cracked. He cracks very easy.” When Dennis talks about Joseph now, Laufgas says, he calls him by that old nickname, the Trembler.

After all this time, Joseph still has trouble reconciling the Dennis who was his friend with the Dennis who bombed abortion clinics. I asked him several times why Dennis did what he did. “I don’t know,” he said. But he may have happened on an answer in Performing in Brooklyn, a screenplay Dennis wrote back in 1997 about his life. Before I leave, Joseph gives me a copy. The cinematic version of Dennis Malvasi (or “Danny” in the script) is a pro-life action hero—part Rambo, part Randall Terry. Trained in Vietnam to be a killing machine, Danny comes home to a world he doesn’t understand. He rips off some guys who are criminals anyway, and goes on the run from the police, all while performing onstage in plays. Danny’s life changes forever, though, when he discovers the remains of aborted fetuses in a Dumpster outside a women’s health clinic. He has a flashback to Vietnam, the sight of bullets tearing the womb of a pregnant villager, her baby spilling out onto the ground next to her corpse. Danny goes to confession for the first time in years, and the priest tells him he’d been blessed with a moment of grace: He’s been a soldier for the military and then a soldier of fortune. Now he’ll be a soldier of Christ. That’s when the bombings start.

In the screenplay, as in life, the cardinal comes forward to plead with our hero to surrender. But in Dennis’s script, the cardinal is a patsy, duped by law enforcement to lure Danny into the hands of a malevolent government. The movie of Dennis’s life concludes with the hero walking into the trap, but at least his conscience is clear. “I’ve always followed my heart,” Danny says at the end, on his way to prison. The cardinal is wrong. Danny—Dennis—is a martyr.

The Bomber and the Assassin

1986

One of the abortion clinics that Dennis Malvasi attacked: the Eastern Women’s Center in Manhattan.

1987

Malvasi turning himself in to authorities.

1989

Barnett Slepian.

1998

James Kopp killed Barnett Slepian in the kitchen of his home outside Buffalo.

1999

The FBI wanted poster for Kopp.

1998–2001

Kopp spent two and a half years running from police, moving from Buffalo to Mexico, London, Ireland, and France.

2001

Kopp leaving a courthouse in France; he was later extradited to the United States.