One could argue that Bob Kerrey had experienced far worse in his life than the eloquent earfuls he got on the morning of December 16. But the meeting, convened by the former senator on short notice in the New School’s Tishman auditorium, still could not have been easy. Just days before, 94 percent of the full-time faculty had given Kerrey a vote of no confidence. About ten students, all with duct tape over their mouths, had plunked themselves down in the second row and refused to leave. (Two days later, an even larger group would occupy a dining hall for more than 30 hours.) The proceedings themselves were mostly civilized, with faculty standing patiently in the aisles and waiting their turns at the microphones, but there were over 200 of them, and few on his side. Arien Mack, editor of Social Research, told Kerrey he was destroying the university to which she’d dedicated her life; Robert Polito, director of the writing program, told him the fall semester was “the most institutionally difficult, troubling, and simply worst” that many of his colleagues had ever experienced. When the Town Hall concluded, the philosopher Richard Bernstein took the microphone. “There’s been much discussion today about what a no-confidence vote means, Bob,” he told Kerrey. “I’ll tell you what it means. It means the most important thing it can mean at a university. It means you’ve lost the trust of your faculty.”

Weeks later, as I sit down with Kerrey to discuss this vote, he repeats to me, with heartfelt sincerity, what he told his faculty: Yes, he recognizes there are problems with his leadership, particularly his habit of tearing through provosts like popcorn, and he’s working on them. But he also sounds annoyed—and suspicious of, rather than chastened by, the near unanimity of the vote. “There’s tremendous peer pressure,” he says. “It’s impossible not to have significant minorities of the faculty saying, ‘All in all, it hasn’t been bad—pay’s gone up, we got tenure, there’s more of us, we’ve got a faculty senate, we’ve got a student senate, he answers our e-mail … ’ ”

All of which, in fact, is true. “One of the most eloquent persons speaking in that meeting was a woman who’d been here for two weeks,” Kerrey continues. “Two weeks.” A note of exasperation creeps into his voice. “Except for the fact that I was taking the blows, I’d have said to her, ‘What do you know about me? How is it possible that the turnover in the provost’s office has produced problems for you? How?’ ”

When Bob Kerrey took over the New School in 2001, the place was so lacking in structural coherence it’s a wonder the Army Corps of Engineers hadn’t been called in to join him. The university was positively Frankensteinian in nature, an awkward body of seemingly random parts. It consisted of eight separate schools, the most locally well known of which was the New School for General Studies, which includes the continuing-education program, offering night courses in everything from Mandarin to the science of farming. Few seemed to realize that Parsons, the design school since made famous by Project Runway, was a part of its solar system, as were three separate conservatories for classical music, jazz, and acting. Eugene Lang College, its undergraduate program, had little national reputation. Neither did the Robert J. Milano Graduate School of Management and Urban Policy. Only the New School for Social Research, its graduate division with a storied history of sheltering Jewish intellectuals during the thirties and forties—Erich Fromm, Leo Strauss, and Hannah Arendt among them—had a national profile, but it seemed to function in a hoary universe of its own.

And in some ways, this was the challenge facing Kerrey when he arrived, and it’s one he still faces today. As he likes to say, the New School was developed bass-ackward, with the New School for Social Research—once known as the University in Exile—at its heart. Most universities start with undergraduate programs, which, through tuition, subsidize those graduate divisions—no university ever got rich off the study of Hegel alone. But Lang, the undergraduate college at the New School, was minuscule in 2001, with just 662 students. The university has never had a strong tradition of alumni giving; even today, eight years into Kerrey’s tenure, the endowment is a mere $169 million. (In late September 2008, NYU’s was still $2.5 billion.) It’s subsidized mostly by Parsons, a sensation since Project Runway, whose students number more than 4,200, and whose professors work in cramped quarters for little pay. “At the moment,” says Jay Bernstein, another highly regarded philosopher at the NSSR, “we’re living off a TV program.”

But the problems with the New School aren’t only financial. They are also existential. The University in Exile served a purpose, absorbing academics that couldn’t be absorbed elsewhere, who in turn offered their distinct brand of radical thought. Today, Jewish intellectuals can find employment wherever they like. There are still departments of the former University in Exile that are highly regarded, like psychology and philosophy. But the NSSR doesn’t define the school in the way that it once did. The place needs to redefine itself, to find the next frontier. It’s a tall order. Though as Leon Botstein, the polymath president of Bard College, points out, it’s not an insurmountable one. “The advantage the New School has,” he says, “is that it’s not hamstrung by its overwhelming prestige and success.”

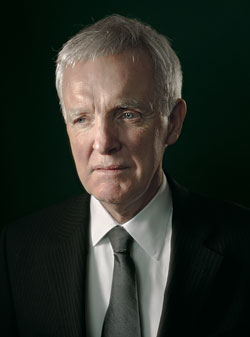

In some ways, Kerrey, 65, seemed like the right guy to revitalize the New School when he took over in 2001. In Congress, where he served as a Democratic senator from Nebraska for two terms, he had a reputation for being more charming than most senators, and far funnier, and possessed of a much lower threshold for fakery (he once called Clinton “an unusually good liar”). One sensed he didn’t have quite as much invested in politics, because he’d seen much worse horrors, having lost the lower part of his right leg in the Vietnam War. He spoke with fluency and confidence about policy matters. As a former businessman, presidential candidate (he ran in the 1992 primaries), and head of the Democratic Senatorial Campaign Committee, he was well connected to the worlds of finance and real estate. He seemed to have the idiosyncratic sensibility to pull the place together—his hometown paper called him “Cosmic Bob” for his far-out ideas—and there was no doubt he’d draw publicity, given the glamorous company he keeps and his facility for repartee. In his single days, he dated Debra Winger, whom he met when he was Nebraska governor and she came to Lincoln to film Terms of Endearment. Kerrey managed to silence all press speculation about their relationship with just ten words: “What can I say? She swept me off my foot.”

But there were ways in which Kerrey was a nonobvious and risky choice. He was not, for instance, an academic himself. He was also a bit of a flake and preternaturally restless, always looking for the next thing. During his tenure at the New School, he’s contemplated both rerunning for a Nebraska Senate seat and throwing in his name for New York City mayor. How attentive can a man be to his day job if he’s still got an oar in the political waters? “I had to seriously look at the Nebraska Senate seat,” he says when I ask about this. “I don’t apologize for that.”

Fine, I say. And mayor of New York? “I do apologize for that,” he says, smiling. “That was dumb.”

Perhaps more than anyone, Jim Miller has been the public face of the New School faculty’s discontents. As a professor of political science and co-chairman of the faculty senate, he’s got a keen understanding of university Byzantium. Talk to him for five seconds, and you get the professors’ concerns in a nub. “Bob gets what’s fucked up about the New School,” he says, “but he doesn’t get what’s special about it, its special anarchy and founding moments. He just sees it as an economic puzzle to be solved.”

Miller and I are sitting in a café, and he’s trying to prepare me for my first meeting with Kerrey. “One way to look at this, which Bob may try to spin,” he says, “is that this is about the conservative, stubborn faculty trying to sandbag crisp new attempts at efficiencies and synergies.” He bears an unnerving resemblance to Philip Seymour Hoffman playing Lester Bangs in Almost Famous, a fact that may be explained by his old life as a rock critic for Newsweek and Rolling Stone. “But our university is not one size fits all,” he says. “You have these bozos telling us that admissions should be centralized. Or advising. Which was really bananas … ”

From the very beginning of Kerrey’s tenure, the New School faculty have complained that he has privileged business over scholarship, especially those who teach at the NSSR. The school has always cost more than it’s generated in income. A former NSSR dean, Kenneth Prewitt, tells me he became so self-conscious about his role as the head of a money-losing operation—“it was as if Bob wanted to stamp a big D on my forehead, for deficit problem”—that he eventually drafted a proposal to sell the division to Bard. (Kerrey didn’t want to go that far.) Prewitt quit in March 2002, after Kerrey proposed cash bonuses to deans who increased their enrollments by a certain percentage, an idea Prewitt found totally distasteful. “The funny thing is, I found myself in agreement with Bob 70 or 80 percent of the time, including on political matters,” says Prewitt, now a professor of public policy at Columbia. “But when he got university matters wrong, he got them so wrong I didn’t quite know what to do.”

Kerrey has had a lot of ideas about how to increase the New School’s solvency and raise its profile, some nuttier than others. (“He has an idea a minute, which can be frustrating, because they’re half-baked,” says one trustee, who declined to speak for the record.) But one idea the board liked was to replace the somber NSSR building at 65 Fifth Avenue with a splashy signature building. Unfortunately, even that caused its own mini-scandal, with the renowned architect Frank Gehry publicly complaining that Kerrey had offered him the commission at a dinner in 2004, then withdrawn it. (“I don’t know what Frank Gehry was smoking, oh my God,” Kerrey later tells me. “There were like 100 witnesses at that dinner.”) Nor were the faculty especially thrilled with the idea of a new structure: That’s what Kerrey wants to do with the New School’s money? Invest in a building, rather than professors and student aid? “What I’m laying out to you is a saga of monumental academic mismanagement,” declares Miller. “You can’t have coherent academic planning when the financial side is driving itself into a ditch. In an academic sense, it’s analogous to what Bush has done to America.”

As a rule, Kerrey doesn’t have a lot of patience for Bush analogies, and he didn’t appear to have a lot of patience for questions about the building, either. The NSSR faculty was asked to pack up its offices and move to new quarters. More important, he pressed on with his plan to keep expanding the university—the number of students at Lang has already doubled since Kerrey’s arrival, to 1,347, and the Parsons student body has already grown by almost 60 percent—so that the building might be paid for, along with the university’s other money-losing operations. Professors would likely have to teach more classes, and larger classes, probably for no extra money. Yet most faculty say they would have been fine with all of Kerrey’s proposals (and then some) if he’d done one simple thing: Consult them. “He saw us as employees,” says Prewitt. “And senior faculty don’t think of themselves as employees of the president.”

“Bob gets what’s messed up about the New School, but he doesn’t get what’s special about it,” says a professor.“He just sees it as an economic puzzle to be solved.”

At most universities, whenever major academic adjustments, like the ones Kerrey is proposing, are in the offing, the provost, or chief academic officer, spends hours talking to deans and professors, trying to figure out what they need. But the New School has never been a traditional university with a traditional provost’s office, and Kerrey, the faculty complain, wouldn’t have the faintest idea how to empower a provost even if it were, because he’s a business guy at heart. Under Kerrey, power has mainly been exercised by a closed loop of New School administrators. They give orders, and faculty are expected to follow. And to faculty, the guy with the most academic power—including the power to help decide who gets hired and fired, and how to manage enrollments—is a fellow named Jim Murtha, the executive vice-president. In conversation with professors, he tends to earn comparisons to either Iago or Dick Cheney. (“Even I’ll admit Jim’s very difficult,” says Douglas Durst, a trustee and the real-estate developer in charge of the new building. “But everyone I deal with on the private side in that role is difficult. They have to be.”)

So in December, when Kerrey announced that his fifth provost, the much-beloved Joseph Westphal, had resigned, and gave a dubious explanation, the faculty flew into revolt. “He doesn’t realize that the provost is the symbol of the academic community and its values,” says Jay Bernstein. “And that’s why the whole series of firings, no matter how justified any single one of them might have been, felt like an assault on the heart of our academic life together.”

“If you asked 100 people what the No. 1 problem is in higher education today,” says Kerrey, “my guess is that 80 would say, ‘The costs are going up at a higher rate than the rate of inflation.’ ” Miller was right. Kerrey is talking about synergies and efficiencies. In fact, he’s talking with gleeful, provocative enthusiasm about synergies and efficiencies. “But in higher education, you can’t talk about productivity,” he continues. “You’re not allowed to have metrics. It’s anathema.” He mentions that tuition will go up 4 percent this year. “And we’re at the lower end of the scale! And there’s still going to be a ten-point margin between our rate increase and the standard of living in our customers.”

These are sympathetic, reasonable points. But he’s just referred to his students as “customers.”

“So, to steal a health-care phrase, I want the New School to start organizing high-quality affordable higher education,” Kerrey says. “And the only way your prices can stay below the rate of inflation is for productivity to go up.” Which means his faculty will have to teach more and bigger classes. “Go talk to the University of Phoenix!” he tells me excitedly. “They have metrics. I’m not talking about transforming the New School in that fashion, but … ”

Good, I interrupt. You’d have an even bigger revolt on your hands. The University of Phoenix is an online diploma mill.

“Yeah, well.” He throws up his hands. “At the moment, in terms of performance, they’re eating our lunch.”

Talk to the trustees of the New School, and they’ll tell you that some of the complaints Kerrey’s fending off are silly. Like charges that the financial health of the New School is poor, for instance: It’s quite good, in strange part because the board includes a number of World War II refugees who were wary of risky stock investments. Or that the new building is disastrously irresponsible: Yes, Kerrey may be handling it like a clod, and the recession timing may be unfortunate, but a new building, per se, is not a dumb idea. “As a person who’s lived in the Village for twenty years,” says Michael Fuchs, a trustee and former CEO of HBO, “I wasn’t even aware of the ingredients of the New School until I was invited on the board. It certainly needed some unification, both geographically and otherwise.”

Kerrey may also talk with perverse delight about the wonders of the University of Phoenix, but he understands perfectly well that most universities are not, in fact, businesses like G.E. “I have come to terms, comfortably, with what my central responsibility is,” he says, “which is to create an environment where there is a separation between faculty and market forces.” And faculty, Kerrey notes, have gotten their way far more in the last eight years than they might wish to acknowledge. There’s a faculty senate now, though Murtha opposed one, and the number of tenured faculty has more than doubled, though Murtha opposed that, too. The New School endowment has also nearly doubled (it was more than that, pre-recession), which for a university with little tradition of alumni giving is pretty impressive, and the school has seven new dorms. One could persuasively make the case, in fact, that Kerrey has given his angry faculty and students the very means they now have to rebel. “He’s tried to make this institution into a university,” says Franci J. Blassberg, a partner at Debevoise & Plimpton and a vice-chair of the board of trustees. “Has everything been handled perfectly? Probably not. I’m sympathetic with many of the faculty concerns, but as growing pains go, these haven’t been that bad.”

“You know who the angriest students were?” asks Kerrey about the occupation. “The students who wanted to get into that cafeteria to study.”

Just months into Kerrey’s tenure, in 2001, The New York Times Magazine and 60 Minutes II jointly broke a story revealing that Kerrey had led a Swift Boat raid in Vietnam that left some dozen civilians dead. His recollection of the incident differed significantly from that of one of his fellow SEALS—Kerrey claims he thought he was returning fire from the village, whereas the other SEAL says he knew he was slaughtering civilians—but no matter which version was true, the outcome was the same: Women and children were dead, and Kerrey would have to live with this fact for the rest of his life. “I thought dying for your country was the worst thing that could happen to you,” he told the Times, “and I don’t think it is. I think killing for your country can be a lot worse.”

Kerrey’s agony didn’t earn him much sympathy at the New School. Some faculty speculate that the university reaction to this revelation may have been the beginning of the end for Kerrey, souring him early, creating a bunker mentality. (Literally: His office in those days required extra security.) Graffiti started appearing on campus calling Kerrey a war criminal, a moniker students would freely hurl at him when they saw him on the street, and one they still haul out with bitter regularity today. His faculty also started demanding explanations. So Kerrey held a series of meetings where he spoke honestly and emotionally. According to a number of people who attended them, he promised to process this experience through the university itself, by planning seminars on war and memory and sending textbooks to Vietnam. “I remember Bob saying he’d devote a third of his life to addressing the postwar traumas and conditions of Vietnam,” says Prewitt. “And that all faded away.”

Memory and war is indeed a funny thing. As we’re bumping along in his Town Car, I bring up these promises. Kerrey cuts me off. “I’ve heard that from so many people, and it’s not true.” I’ve heard many times that Kerrey is quick to anger, but this is the first evidence I’ve seen of it. “I didn’t talk about … seminars.” He practically spits out the word. “I said I’m going to spend the rest of my life coming to terms with this, and I am. It’s none of their goddamn business any longer. None of their business. This is one where I reserve the right to come to terms with it in a way I choose to come to terms with it, not theirs.” He shifts in his seat, still agitated, and as I try to make it clear to him that I sympathize, he continues talking right over me. “Their idea to come to terms with it is you have seminars and you apologize and put the hair shirt on. That’s not my idea.”

So I start talking over him, telling him my sole point was that the faculty were under the impression he’d broken a promise to them. “If they can find one quote where I promised it,” he says, “I’d look them in the face and say that’s one promise I’m breaking.” He exhales and looks out the window. Then he turns back at me, smiles, and changes the subject.

If you’re the CEO of McDonald’s, it helps to like burgers. And if you’re the president of a university, it helps to like academic culture. One of the most frequent complaints about Kerrey is that he doesn’t. “He seems bored when he has to officiate at some academic setting,” says Arien Mack, who’s edited Social Research since 1970. “I don’t think what we do matters to him.”

Kerrey himself admits to a certain disconnect. He never taught a course, never cultivated a kitchen cabinet of faculty confidants. “In some ways,” he says, “it’s too late for me to acquire a detailed knowledge of the culture of higher education.” I tell him a knowledge of academic culture probably isn’t necessary; a simple appreciation would do. Does he attend student events?

“Yeah!”

How many?

He’s quiet. “Jesus. I don’t know.”

Does he host receptions?

“Yeah.”

How many?

“I have one big one every year, and two smaller ones each semester.”

Compared to his predecessor, though, that’s peanuts. Do you ever have faculty over to dinner?

“Yeah.”

How often?

This time he’s silent for quite a while. He looks directly at me. “Maybe I should do it more.”

“Being a president of a university is like being a bus driver for a group of people who are all probably better drivers than you are,” says Leon Botstein. “They’re not doing this for the stature or financial reward. Their reward is that they’re at the center of the enterprise, in the sense that they’re treated with respect and honor.”

Prewitt says Kerrey never grasped this simple, crucial fact. “He read the graduate faculty as two things,” he says. “First, as an economic drain, and second, as institutionally selfish—they want their leave, they want their tenure, they want low teaching loads.”

The problem, of course, is that this assessment contains more than a grain of truth. Professors do want all those things. They are also famously unshy about picking fights. (One thinks of the line commonly attributed to Henry Kissinger: “Academic politics are so vicious precisely because the stakes are so small.”) Prewitt concedes as much. “I’m not defending them,” he says. “I find faculty everywhere are smart in general. But that doesn’t mean they’re sane.”

Here’s what’s strange: In the Senate, collegiality is the coin of the realm. Without a high threshold for stubborn, fragile egos and an ability to work with people whose ideas are different from your own, senators would get little done. Kerrey understood this well. During his twelve years on Capitol Hill, he established himself as a warm and affable part of the club. Then he got to the New School and drew the curtains around himself. How could one of the best politicians in the business forget the simple value of politics?

To some extent, the answer may boil down to a fundamental mismatch of sensibilities and temperament. “Academics never met a meeting they didn’t like,” says Miller. “But Kerrey has a very short attention span. He likes to be amused and entertained; he shoots from the hip. He’s at his best when he’s at a meeting and people are sententious and pompous. He just punctures that.” Kerrey’s old friend the retired U.S. Army colonel Jack Jacobs adds that Kerrey’s experiences in Vietnam probably made his impatience with academic process all the more acute. “When your life is annealed in the intellectual crucible of war,” says Jacobs, “you have a tendency to focus on crap that’s important in the overall scheme of things.” Sure, he says, Kerrey could have spent more time having the faculty to dinner. But if they weren’t his friends, why bother? “Bob’s a very sociable person,” says Jacobs, “but he doesn’t like faking it. He’s the one who looks at Cyrano’s nose and says, ‘You’ve got a hell of a hooter on you.’ ”

But there’s probably an even simpler, if counterintuitive, explanation for Kerrey’s failure to connect to his faculty: He finds the New School less respectful of intellectual difference than is the United States Senate. “Part of the problem I have with the faculty is, I like to argue,” he says. “And particularly here at this university, where we pride ourselves on critical thinking, we ought to be able to have an argument. You want to take a position on the Iraq War, fine, let’s have an argument!” Kerrey was in favor of the Iraq War, to his colleagues’ dismay. “But if you begin by saying, ‘Oh, your argument is unacceptable,’ what kind of university is that?”

He thinks, and brings this point closer to home. “You got a guy here you don’t like, Jim Murtha, and you call him Dick Cheney,” he says. “It’s a demonstration of how we talk about critical thinking but don’t do it all the time. It’s jerky to call him Dick Cheney. Maybe you get a round of applause and people laugh, but how are you different from kids on a street corner harassing a teenage girl?”

Kerrey got to experience this in a different context in 2006, when he invited John McCain to speak on graduation day. Perhaps 200 or so students out of the 8,000 graduates turned their chairs to face the back of the auditorium as he addressed the crowd. “We behaved reprehensibly,” says Kerrey. “I’m not proud of it. I’ve learned my lesson. I don’t invite controversial speakers to this school, especially if they’re my friends. We want to invite people who agree with us.”

I mention what one of the student negotiators during the cafeteria occupation, said to me—that to invite McCain was “to disregard the ideals of the New School.”

“Yeah, I’m sure that’s a persuasive argument to half our students, who are at Parsons,” says Kerrey. “They’ve come here because of the liberal fashion program we have. I’m sure that students at Mannes say, ‘Yes, I want to play the violin, but it’s the progressive politics of the New School that have brought me here … ’ ”

Fair enough, I say. But why provoke the kids who’ve come here for that tradition?

“It’s the minority,” he says. “The majority would like to have those kinds of critical debates, but, as is almost always the case, they get shouted down by a minority. You know who the angriest students were during the occupation? The students who were trying to get into that cafeteria to study.”

If Kerrey has no great love of academic culture, one might wonder why he accepted the New School job in the first place. Kerrey himself hints at a possible explanation—or at least an explanation for why he came to New York. While he was in the Senate, he fell in love with the screenwriter Sarah Paley, who was living in New York City. “And you know, love conquers all,” he says. “She wanted to have a baby, and I didn’t want to raise another kid in politics, so, okay, now I’m coming here.”

Kerrey insists the job of New School president genuinely interested him, and that he still quite likes his job today. And the board doesn’t seem particularly interested in getting rid of him, though the trustees are insisting he balance the power between the administrative and academic sides of the university. Just last week, Kerrey issued a letter to the entire university, announcing a number of concessions to his faculty. But many professors are so angry that they seem obdurately disinclined to take yes for an answer. At an emergency faculty meeting two weeks ago, several senior people raised the possibility that the school might need to schedule a second no-confidence vote. At one point, a student from NSSR, Geeti Das, stepped up to the microphone. If Kerrey didn’t resign by April 1, she said, “We will shut down the functions of the university. We will bring it to a halt.”

By the end of the meeting, it was hard not to sympathize with Kerrey. The gathering had become a de facto faculty-senate session, with people proposing amendments to motions and motions to amendments—just the sort of endless ping-pong that drives him nuts. The room became an accidental signifier of the seventies, a sea of black jackets and Elvis Costello glasses and long hair. For an outsider, it was hard not to look around and think: These are the kinds of people who’ve given Kerrey grief from the moment he came home from Vietnam.

In the final minutes of my last interview with Kerrey, I mention that a faculty member told me the New School could probably make all the changes Kerrey sought if only Kerrey agreed to pack up and leave. “I’ve thought about that,” he says. “The evening I was sitting with my 7-year-old with a bunch of screaming maniacs outside my building, I was thinking, Who needs this?” He recognizes that this situation is tenuous. Just a few minutes earlier, he’d told me as much. “I don’t think it’s ungovernable,” said Kerrey, “but it may be. It may be that they need to find somebody else to run this place.”