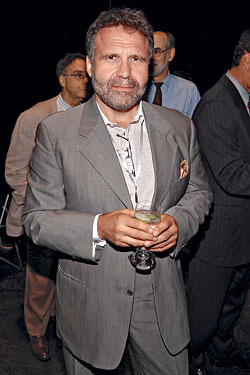

There was a time when Marc Dreier thought he could talk his way out of anything. But by last fall, even he was scrambling. Whenever the stylish, hyperaggressive 58-year-old white-collar litigator turned around, clients and colleagues at Dreier LLP, the marquee Park Avenue firm he’d built from almost nothing to 250 lawyers in just five years, were asking questions—about back rent, unpaid loans, depleted client escrow funds, documents of uncertain provenance. What Dreier needed to make these questions go away, he knew, was money. About $40 million, for starters.

On Tuesday, December 2, Dreier boarded a private jet and flew to Toronto. When he landed, a driver brought him to the financial district and pulled up to the stout, glass-encased Xerox Tower. Dreier climbed out of the car and walked into the building. He was expensively dressed, but short and perma-tanned, with a thatch of gray hair swept over a sizable bald spot. He rode the elevator to the third-floor offices of the $100 billion Ontario Teachers’ Pension Plan, one of the largest retirement funds in Canada. Dreier had arranged a meeting with one of the plan’s in-house lawyers, Michael Padfield, ostensibly to discuss business opportunities. But Dreier had other motives, and the meeting lasted only briefly. Before saying good-bye, Dreier asked for a place to wait until his plane was ready. He was sure to take Padfield’s business card.

Dreier dropped his things in a conference room, then went to the lobby, where he paced for an hour and eyed the entrance, until he spotted Howard Steinberg, an executive with a $34 billion New York hedge fund named Fortress. Steinberg and Dreier had never met, but they had been in touch earlier, when Steinberg had been trying to confirm the authenticity of some documents Dreier had sent him, promissory notes said to be worth $44.7 million that Dreier was offering to sell to Steinberg. When Dreier had told Steinberg the notes were guaranteed by the Ontario Teachers’ Pension Plan, Steinberg had asked to meet with someone from the fund personally. Dreier told Steinberg he’d arrange a meeting with Michael Padfield.

Dreier worked Padfield’s business card into Steinberg’s hand. Upstairs in the conference room, Dreier showed Steinberg some papers signed in Padfield’s name. But the meeting didn’t go as planned; Steinberg sensed something was off, and Dreier ended the meeting abruptly and went straight for the elevator. When he was gone, Steinberg approached the receptionist and asked her a simple question.

“Was that Michael Padfield?”

“No,” said the receptionist, “it wasn’t.”

We live in an age of white-collar villains. But of all the financial bad guys out there, Marc Dreier is arguably the single greatest character of them all. Bernie Madoff may have stolen more money. Dick Fuld may have caused more systemic damage. But it’s Dreier alone whose story reads like the stuff of Hollywood. Dreier isn’t just accused of swindling more than $400 million from thirteen hedge funds. Prosecutors say he carried out the deception by inventing $700 million in financial assets out of whole cloth, staging fictional conference calls, and impersonating executives, sometimes personally, sometimes with the help of an associate, all while snapping up Warhols and waterfront homes, partying with pop stars and football players, and chasing an endless parade of much-younger women. He also allegedly stole some $40 million from his clients’ escrow accounts, a brazen legal sin. Unlike Madoff, who worked from behind the scenes in the Lipstick Building, Dreier took a starring role in his own financial drama. Where Madoff was outwardly quiet and self-effacing, Dreier was openly egotistical, even smug. He seemed to think he could lie to his victims’ faces and get away with it, to thrill, even, in the art of deceiving people. It’s been suggested that Bernie Madoff was a pathological liar. With Marc Dreier, there appears to be little doubt.

Like any accomplished confidence man, Dreier had a signature modus operandi. Just weeks before his Toronto performance, he had staged a similar show here in New York. On Wednesday, October 15, Dreier allegedly walked into the lobby of 9 West 57th Street, the tan, sloped skyscraper off Fifth Avenue, and took the elevator to the 45th-floor offices of the billionaire real-estate developer Sheldon Solow. Although the two men rarely worked together anymore, Solow had once been one of Dreier’s most valuable clients. Dreier didn’t have an appointment, but he told the receptionist he did and she let him through. Again, Dreier set up shop in a conference room, then returned to the reception area and waited.

Before long, a man about Dreier’s age named Kosta Kovachev arrived. For the past several years, Kovachev had worked as Dreier’s aide-de-camp—employed not by Dreier’s firm but personally by Dreier. Dreier walked Kovachev to the conference room and left him there, then turned around and came back to the reception area to wait for his other guests.

When the others arrived—two hedge-fund executives, both from the same firm—Dreier brought them to the conference room, where he and Kovachev fielded their questions. At one point, Steve Cherniak, the CEO of Solow Realty, walked past, saw the meeting, and shrugged and went on his way. But had he joined the meeting, he would have learned that the hedge-fund representatives believed they were there to see Steve Cherniak—the man they were told was sitting next to Marc Dreier.

Dreier had been running similar scams with different marks, prosecutors say, since 2004. Dreier would allegedly contact an investment fund like Eton Park, Fortress, GSO Capital, Westford Global Asset Management, Perella Weinberg, and, before it went under, Amaranth and say that his client, Sheldon Solow, was trying to finance his real-estate projects by borrowing money with promissory notes. Dreier wasn’t a financier; he was a lawyer. But he would tell people he was working as a marketing agent for his client Solow’s securities. Solow, it appears, knew nothing about what Dreier called the “note program,” but that didn’t stop Dreier from sending along various offering materials—information about Solow, phony notes and financial statements on fake letterhead from Solow’s auditing firm, e-mails that he said had been issued by Solow, and so on. Dreier and his accomplices forged the notes themselves, complete with the fake signatures of Solow executives. If anyone asked to meet someone in the Solow organization, Dreier would arrange conference calls with people posing as Solow executives. He set up phone lines at his law firm. He created fake e-mail addresses. He kept hard-to-trace, no-contract cell phones—“burners” like Tony Soprano used—in a box in his office. Last July, Dreier diversified beyond his Solow strategy, selling $52 million in phony notes he said were issued by the Ontario Teachers’ Pension Plan. He used part of the proceeds to pay interest on some of the Solow notes he’d already sold.

Dreier’s motives were at once shallow and profound. Even by New York standards, he was wildly ambitious. It wasn’t enough for him to be a successful lawyer; he had to be the most successful lawyer in town, and he needed everyone else to know about it. You could see his obsession reflected in the $10 million Beacon Court condominium, the fully staffed $18 million 123-foot yacht, the $40 million in Warhols and Lichtensteins and other artworks, the Aston Martin, BMW, and two Mercedes, the two Hamptons homes, the Anguilla property, the Park Avenue headquarters with his name emblazoned on the side, the star-studded charity golf tournament, the girls. When he’d couldn’t come by all of that honestly, it seems, he found another way. The whole operation was audacious to the point of sheer recklessness—from the start, he was just one due-diligence phone call from being found out—yet the very boldness of his plan was central to its success. Who would believe that such a respected and apparently successful attorney would knowingly peddle hundreds of millions of dollars worth of nothing?

Marc Dreier seemed born to be a player. The son of a Polish war refugee who settled in Long Island, Dreier was voted most likely to succeed by his graduating class at Lawrence High School in the Five Towns. At school, Dreier was more of an intellectual than a jock and presided over the student council. Friends remember him driving his Oldsmobile 442 with the top down and dating the prettiest girl in school. “The fact that the guy remained the big man on campus later on in life, that surprises nobody,” says classmate Kenneth Gross. “He had that flash in him from his early days.” Next came Yale and Harvard Law. “He had a plan even then to do well,” says Henry Kass, another old friend. “The mantra for all of us was ‘Be somebody.’ ”

After law school, Dreier went to work as a white-collar defense litigator at the New York firm Rosenman & Colin. “He was one of the shining stars,” says Donald Citak, a former colleague. “He was ambitious, bright, and full of energy—hyper but personable.” Dreier pitched on the company softball team and was always up for drinks, often at the Beach Café at 70th Street and Second Avenue, a few blocks from his bachelor apartment on York Avenue. But even Dreier’s friends didn’t fully trust him. “He never put other people’s interests first,” one friend says, “and he’d make no bones about it. Part of him wanted to have friends, but all of him wanted to be admired.”

Dreier left Rosenman in 1989, then worked at two other firms before starting his own shop with a lawyer from Boca Raton named Neil Baritz in 1996. Dreier & Baritz’s first major client was Sheldon Solow, one of the city’s real-estate titans, who, like Dreier, was wildly ambitious and had a taste for expensive art. Solow already had a reputation as one of the most litigious real-estate developers in town, suing rivals, tenants, even tenants’ houseguests. Dreier only enabled Solow’s habit. In one matter, Dreier filed eight different lawsuits on behalf of Solow in thirteen different states and federal jurisdictions—losing every time but still appealing. Opposing lawyers say Dreier was a shark. “He was the type of guy who would do anything a client asked if it was in his interest,” says Kevin Smith, a lawyer who faced Dreier in court many times. “Everybody draws a line at some point. But this guy, he would do anything. Every courthouse, he’d pull up in a limo. He had suits that were cut, watches, jewelry. He was nasty, very aggressive, and contentious. He treated me like I didn’t exist.”

Early on, Dreier & Baritz sought to expand by establishing limited partnerships with lawyers in other cities. In 2001, an Oklahoma City attorney named William Federman sued Dreier, saying that Dreier owed him money, and, worse, that Dreier had failed to offer a proper accounting of Federman’s client escrow funds. Federman settled with Dreier in 2002. That same year, Neil Baritz left the firm. He has said that he left “for personal reasons and because our businesses were no longer compatible.”

In 2003, Dreier took his small firm of 30 lawyers and rechristened it Dreier LLP. It was an odd time to embark on an expansion. Not only had his partner just left him, but Dreier had cash-flow problems. He had secured a revolving credit line in 2001 for $750,000, which he amended a year later to $2 million, with another $2 million in outstanding debt, and now needed to refinance yet again owing to lack of payment. He was also getting divorced: He had married an associate at Rosenman & Colin named Elisa Peters in 1987; the couple had a son, Spencer, in 1989, and a daughter, Jackie, in 1992, but now Elisa was divorcing him. (The matter dragged on for six years, in part, a source says, because Elisa claimed Dreier was hiding assets from her.) But friends and former classmates were surpassing Dreier, and that seemed to chafe him. One former colleague, Marc Kasowitz, had already won a historic tobacco-related settlement that Dreier couldn’t help but notice. Kasowitz had left Rosenman to start his own firm, just like Dreier. But Kasowitz was doing far better. “Dreier wanted the big cases,” says a friend. “His firm wasn’t doing anything that looked really impressive. I think that bugged the shit out of him.”

Whether Dreier expanded his firm to make money to pay the interest on his phony notes or sold his phony notes so that he could expand his firm is an open question. What’s clear is that the firm grew dramatically. Dreier lured away entire departments from other shops, establishing practices in everything from bankruptcy and tax law to sports licensing and entertainment, and bringing the firm’s total number of lawyers to more than 250. With the new acquisitions came high-profile clients, such as Jay Leno, Wilco, and Michael Strahan. Dreier moved the company’s offices to 499 Park Avenue, the sleek I.M. Pei–designed former Bloomberg headquarters (complete with private entrance), and opened satellite branches in Stamford, Connecticut; Albany; Pittsburgh; Los Angeles; and Santa Monica. One source says Dreier hired an aircraft to fly over a party he was hosting in the Hamptons displaying the firm’s name. “He was charming, gregarious, sure-footed, and clear-thinking,” one lawyer says. “It seemed like he built just what he said he would build—a large, successful, bi-coastal firm.”

To finance the firm’s expansion, Dreier used a risky accounting practice called factoring receivables, in which one borrows money against future income. Essentially, he was leveraging himself not on real assets, but on a wish. Dreier also structured the firm in an unusual way. Instead of sharing ownership with a group of partners, he owned the firm himself. The other attorneys were partners in name, but really employees. Rather than sharing in the firm’s profits and being subject to the ups and downs of its performance, they were paid guaranteed salaries, plus a bonus or commission on new business. Many of them took in salaries of up to $1 million a year, well above market rate. To the extent anyone suspected that Dreier was spending more than he was earning, they assumed, as one friend says, that “he had independent means.” As the firm’s sole equity partner, Dreier had virtually no oversight. He was the lone signatory, for instance, on more than a dozen different escrow accounts that were supposed to be holding clients’ money. The money was supposed to be off-limits, but if he chose to tap it, no one could stop him. Of course, Dreier was also the sole responsible party if the firm couldn’t pay its bills.

Although he was never on the firm’s payroll, Kosta Kovachev was a close associate of Dreier’s. As recently as last year, he had an electronic entry card for Dreier LLP’s offices, and access to the firm’s computers. A stocky and bearded ex-banker in his late fifties, Kovachev was born in Belgrade and educated at Columbia University and Harvard Business School. He lived in Greenwich, Connecticut, for years in the nineties before moving to Florida, but has no recorded residence at the moment, just a cell-phone number that flips over to the Harvard Club. Over the years, he has worked for Morgan Stanley and Drexel Burnham Lambert. But his banking career ended in 2006, when the SEC revoked his broker’s license after a scandal involving a low-level Ponzi scheme to sell time-shares in Florida. Kovachev’s lawyer in that proceeding was Marc Dreier.

Dreier also had ties to a man named Armando Ruiz. “Ruiz had some celebrity relationships, and that’s how they became friends. Dreier wanted to meet celebrities,” says a longtime business associate of Dreier’s. “Every time Dreier had a party, this guy was the one that was putting everything together. He used to hang out with him at his home in the Hamptons all the time.” Ruiz, who did not respond to calls to his last known phone number, was once photographed at Dreier’s golf tournament, smiling alongside Michael Strahan.

A year after Dreier LLP was founded, Dreier was sanctioned by a judge, apparently for the first time in his career. He was cited for planting advertisements made to resemble legal notices in the Times and the Post, listing damaging information about a rival of Sheldon Solow’s. Dreier’s chief confederate in the matter was Kosta Kovachev. In one deposition, Dreier refused to answer his interlocutor’s questions 79 times and threatened to walk out of the room ten times. “I’m not going to sit here and have you waste my day by asking these questions,” he said, until he finally admitted he was working for Solow the whole time. “What I found most peculiar was, even after we had him sanctioned, he was just, ‘So what? Screw you,’ ” says Stanley Arkin, the attorney who exposed Dreier’s role in the smear job. “Some people think they can bull their way through anything.”

The phony note program started that same year, and Dreier was soon issuing more in bogus debt than he was earning in legal work. By December 2006, prosecutors say, one hedge fund alone had invested $60 million in the notes. According to bankruptcy-court records, Dreier LLP’s gross revenue for that year totaled $58 million. By 2008, prosecutors say, Dreier was on the hook for $180 million in phony notes, plus another $20 million in annual interest. That was almost double the firm’s annual revenue.

Dreier was on the hook for $180 million in phony notes—almost double the firm’s annual revenue.

Last fall, on one of the first Mondays in November, Dreier got a phone call from a man he’d never heard of named Tom Manisero, a lawyer who told Dreier that he represented Solow’s audit firm, Berdon LLP. With a Berdon executive sitting in on the call, Manisero told Dreier that someone from Berdon had discovered an audit report on Berdon letterhead that had apparently been used to market some Solow Realty notes to the Whippoorwill hedge fund. Dreier’s name had been mentioned; he was said to be the person marketing the notes. The audit report was, apparently, a forgery.

Dreier was evasive on the phone. “It clearly took him by surprise,” says someone familiar with the call. “He wasn’t angry. He was hemming and hawing a bit. He was trying to give some bullshit story that he was acting on his own, but that Solow was involved in some sort of litigation and they were trying to buy the debt of the person who was litigating.”

The truth is, Dreier already knew that his enterprise was starting to unravel. Investigators now believe that by September or October, Dreier had largely run through his cash and had to sell new phony notes just to pay his bills, all the way down to the firm’s car-service tab. In September, a representative from one hedge fund had contacted Dreier asking why the firm’s Solow notes weren’t being repaid on schedule. On October 17, Dreier had signed a credit agreement with Wachovia Bank for $14.5 million, pulling out $9 million right away. To bring in more money, he also allegedly sold phony notes to two hedge funds in October—Verition (owned by Amaranth’s founder, Nick Maounis), which paid him $13.5 million, and a firm the U.S. Attorney’s Office is not naming, which paid Dreier $100 million. People who knew Dreier well noticed a change in his demeanor. He was colder, more calculating, and “he seemed nervous,” says one source. “There was a manicness to him.”

The call from Tom Manisero appeared to shake Dreier further. Soon after, prosecutors say, he tried to move money into a personal account he used for his Caribbean properties. Dreier didn’t know that the authorities had already been alerted: Shortly after that first call, Manisero along with Solow’s attorneys at Shearman & Sterling had called the U.S. Attorney’s Office.

A few days later, Manisero’s phone rang. It was Dreier again.

“Tom,” he is said to have said, “I need to talk to you.”

“I’ve got an office full of people,” Manisero replied. “I need to call you back.”

What followed were at least a half-dozen phone calls over then next few weeks between Dreier and Manisero, most of them secretly recorded by the U.S. Attorney’s Office. Dreier assumed an accommodating posture, professing to be cooperative and willing to give Manisero whatever he wanted to assure him everything was all right. In one call, Dreier admitted the audit reports were fake, saying he was “ashamed” and that it was “very serious what happened here.” But he insisted it was only this one instance. He mentioned Kosta Kovachev by name, as well as Armando Ruiz.

Manisero told Dreier he didn’t believe this was the only time and asked to talk to the other people involved. Dreier stalled. He began calling Manisero from time to time unprompted, apparently to feel him out about how much he knew. He’d implore him to keep this a private matter because it would damage a lot of people, including his firm and his family. On November 10, Dreier called Manisero from the United Arab Emirates, where he said he was meeting with several businesspeople about the possibility of opening another law office. He also traveled in November to St. Martin and Qatar. Manisero kept asking Dreier for more information about what he’d done, never letting on that the investigation had begun.

The Friday after Thanksgiving, Dreier called Manisero one more time with a different pitch: Maybe there was some way they could settle the matter. “Obviously,” a source familiar with the calls says, “the suggestion was money can buy peace here.”

Manisero’s response, a source says, was incredulousness. Technically, Dreier had admitted only to trying to sell the notes once and not even succeeding. If, as Dreier said, this was the only instance he’d tried, and it had failed, why offer a settlement? “How would a settlement work?” Manisero is said to have said. “I don’t understand it.”

According to the source, Dreier suggested Manisero would sign a release form limiting Dreier’s liability. “It was a real shuck and jive,” the source says—with “a hint of desperation setting in.” It was the last time Manisero and Dreier would speak.

Over the course of these calls, the Verition hedge fund, which had been speaking with Whippoorwill, learned about similar irregularities in its transactions with Dreier and sought to reclaim the $13.5 million the fund had paid him. In November, a lawyer for Verition was asked if the fund ever got its money back.

“We got money back,” a source says the lawyer said. “But I don’t know if it was our money.”

It’s been suggested that Bernie Madoff was a pathological liar. With Marc Dreier, there appears to be little doubt.

On Monday, December 1, another front of trouble opened up for Dreier. A bankruptcy lawyer with the firm named Norman Kinel sent Dreier an e-mail asking for $38.5 million out of the firm’s escrow account. Kinel needed the money for a client that had been dealing with a bankruptcy for more than five years and wanted to use some of its escrowed funds to pay its creditors. But there was a problem. Less than half the needed money remained in the escrow account.

The day after he got the e-mail from Kinel, Dreier flew to Toronto.

On December 3, the phone rang in the comptroller’s office of Dreier LLP. It was Dreier, calling from Toronto. He’d been arrested for criminal impersonation. Someone at the Ontario Teachers’ Pension Fund had alerted the police moments after Dreier was caught pretending to be Michael Padfield, and someone, either the police or a representative of the fund, had reached Dreier on his phone before his plane took off. Dreier agreed to turn himself in. “He was obviously a beaten-down man,” a Dreier LLP source says. “His voice was gravelly, desperate. He said he did wrong, he’d ruined his life and career, and he’d try to make up for it.”

The same day, Dreier’s 19-year-old son, Spencer, walked into the offices of Dreier LLP to deliver a message on behalf of his father. Spencer’s mother, Elisa, was with him. According to one source, Spencer walked into a conference room where about 40 of Dreier’s partners were meeting to discuss what to do. With his mother waiting outside, Spencer delivered his speech. “He said no one should be deserting his father because his father gave them so much,” says someone who was there. “It was bizarre.” The lawyers in the room were livid. One even started shouting: “I’m not going to listen to you! You have no place in here! This is a partnership meeting. You’re not a partner!” Spencer even apparently came back to 499 Park Avenue the next day, trying to get in, when the guards stopped him. “He said, ‘I’m just going up to get some computers!’ ” a source says. “And they said, ‘Well, you can’t. Sorry.’ ”

On December 4, Dreier, still in jail in Toronto, spoke on the phone with two of his partners, Steven Gursky and Joel Chernov, who asked him about the missing escrow funds. Dreier tried to tell the men that had he not been arrested, he would have been able to come back to New York and straighten things out—perhaps by selling some of the firm’s art. Chernov was having none of it. “I understood from this conversation that Mr. Dreier was implicitly admitting that he had improperly used client escrow funds,” he later told the court.

Dreier remained in jail for three days before bailing himself out, long enough for his arrest to make the news and the escrow revelations to spread within the firm. The lawyers at Dreier LLP knew that Marc Dreier was the only thing keeping the firm together. If the only equity partner was stealing clients’ money, the whole firm could implode, leaving 250 lawyers unemployed and potentially exposed to lawsuits from angry clients. “As soon as we heard there was a problem with the escrow accounts, that’s when we knew,” one partner says. “The escrow is the holy grail. You don’t touch escrow unless you have no other option.” Says one close colleague: “I’ve never seen such mass hysteria in my life. People were running out the door, lawyering up. People started to see their careers evaporate.”

During the chaos, Dreier still managed to transfer more money from another escrow fund into one of his personal accounts. The firm’s comptroller, John Provenzano, refused to do it twice before Dreier ordered him to connect him directly to someone at the firm’s bank and then arranged a $10 million transfer himself.

At 2 p.m. on December 4, Kosta Kovachev reportedly went to the fifth-floor conference room at the Park Avenue offices of Dreier LLP, took two paintings, and left in a cab.

Dreier finally made it back to New York on Sunday night, December 7. The escrow matter wasn’t public yet, and one colleague believes Dreier even thought he could still clear everything up before coming under further scrutiny. Maybe he could contain the impersonation arrest, keep the hedge funds at bay, and solve the escrow problem. Maybe Tom Manisero and Norman Kinel and Michael Padfield weren’t talking to one another yet. But it was too late. Dreier was arrested on the tarmac and charged with two counts of fraud. It was then that he learned that the Justice Department had been looking into his business affairs for weeks.

Marc Dreier now spends his days under house arrest in his Beacon Court apartment. His son and mother are guaranteeing his bail and paying the $70,000-a-month costs of around-the-clock security. If convicted, the man one prosecutor calls “a Houdini of impersonation and false documents” faces some 30 years in prison. Dreier has all but confessed to parts of the scheme, and his own lawyer has said he expects his client to plea out before the proposed June 15 trial date. Kosta Kovachev has been arrested, too, and at last report was still in jail. Through their attorneys, both Dreier and Kovachev have refused to comment. Armando Ruiz has not been charged with any crimes, but the government has subpoenaed all documents concerning him from the law firm. Because Dreier was the only equity partner in Dreier LLP, the firm vaporized, as expected, practically the day he was arrested. Many of Dreier’s former colleagues have since joined other firms and argue that they were partners of Dreier’s in name only. What liability they may face is not yet known.

All told, Dreier is accused of selling $700 million in phony notes to thirteen hedge funds and three individuals. More than 200 creditors, including a few hedge funds, have already filed more than $450 million in claims against the firm; Eton Park is seeking $84 million, Fortress wants $61.9 million. Investigators say the money is mostly gone—Dreier spent it on his homes, cars, art, and the like. It’s unclear how much anyone will recover.

It may be true that Dreier was driven by an excess of ambition and ego. “It was always important to him that people thought he was doing well,” says one old friend. “He had his name on that big fucking building on Park Avenue.” And so instead of scaling back or closing the firm or selling the yacht, “he crossed a line.”

Then again, there are those who view him in a darker light. “Marc Dreier has been a shakedown artist his entire career,” says an angry former client. “That’s what he does. That’s how he makes money. He insinuates himself into people’s lives. He gains their confidence. And then he exploits them.”

Additional reporting by Beth Landman.