Yes, 1959. Not 1968 or ’71 or ’64 but the send-off year of the reputedly frumpy fifties was when the shock waves of the new ripped the seams of daily life, when categories were crossed and taboos were trampled. Other years boast transformative events (you can find them in almost any year if you look long enough), but 1959 was especially pivotal, though widely forgotten. It was the year when a rocket first broke free of the Earth’s orbit, the FDA held hearings on the birth-control pill, the microchip was unveiled, the 707 took its maiden nonstop voyage from coast to coast, and Berry Gordy founded Motown. Yet this New Frontier loomed as a place not just for satellites and rockets and a new youthful music but also for ICBMs and H-bombs. And so, 1959 was the year that saw panic over fallout shelters, fears of a “missile gap,” and Strontium-90 in milk. It was also when U.S. military advisers suffered their first fatalities in Vietnam.

The culture was changing, too, as a new generation of artists and writers crashed through their own sets of barriers—and attracted growing audiences that, amid the newness all around them, were suddenly, even giddily, receptive to the iconoclasm. New York emerged as the center of these changes, and it was 50 years ago that the city took on some of its still-familiar contours. That summer, Allen Ginsberg, the generation’s visionary poet of exuberance and doom, wrote in the Village Voice: “No one in America can know what will happen. No one is in real control. America is having a nervous breakdown … Therefore there has been great exaltation, despair, prophecy, strain, suicide, secrecy, and public gaiety among the poets of the city.”

He might as well have written that today.

Ginsberg’s Gap

On February 5, Allen Ginsberg gave a poetry reading at Columbia University before a crowd of 1,400. It was a big night for Ginsberg, his triumphant return to the campus that had suspended him over a decade earlier for scrawling obscenities on a windowpane. But it was also a turning point for American culture; given his bohemian lifestyle and apocalyptic verse, Ginsberg’s very presence, on a stage that had recently hosted T. S. Eliot, was a rousing impertinence. The faculty stayed away, not wishing to grant a “beatnik” the legitimacy of their attendance. Lionel Trilling, who had once mentored Ginsberg, was no exception. But Trilling’s wife, Diana, sneaked in and came away impressed, even moved. She wrote an account of the experience for the Partisan Review, noting “the unfathomable gap that was all so quickly and meaningfully opening up” between those who immersed themselves in Ginsberg’s reading and those, like her husband and his peers, who shunned it on moral principle. It was the first crack in the generation gap.

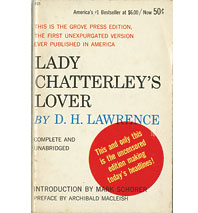

Censorship’s Wane

Barney Rosset, hell-raising proprietor of Grove Press, declared war on anti-obscenity laws by announcing on March 18 that he was publishing the uncensored text of Lady Chatterley’s Lover, D. H. Lawrence’s 1928 novel, banned by the U.S. Post Office for its graphic sex scenes. Rosset’s battle seemed doomed. The Supreme Court had condemned as “obscene” any work whose “dominant theme … appeals to prurient interests.” But at the Manhattan trial, Rosset’s lawyer, Charles Rembar (also Norman Mailer’s cousin), put forth the creative argument that no work can be deemed obscene if it contains “ideas of even the slightest social importance.” U.S. District Judge Frederick van Pelt Bryan found that reasoning persuasive, distribution restrictions were lifted, and the Grove edition of Lady Chatterley went on to sell 2 million copies, sating—and further unleashing— a pent-up hunger for once-forbidden fruit.

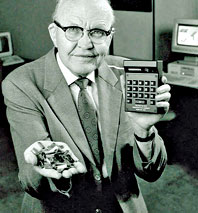

The Microchip

At the Institute of Radio Engineers’ March 24 trade show in the New York Coliseum, Texas Instruments introduced a new device that would change the world as profoundly as any invention of the century—the solid integrated circuit, a.k.a. the microchip. At a press conference, the inventor, Jack St. Clair Kilby, a self-described “tinkerer,” held up the match-head-size prototype while TI’s executives presciently boasted that it would revolutionize not only rockets, missiles, and satellites but also TVs, radios, telephones, and medical instruments.

Fidel’s Visit

On April 15, Fidel Castro, the new leader of Cuba, launched a whirlwind U.S. tour, enthralling millions with a spectacle unseen in their lifetimes: a revolutionary, claiming to be neither communist nor capitalist, who rose to power without the aid of Moscow or Washington and who therefore seemed like he might be the one to carve a new path, a breakout from the Cold War’s grinding duel. In New York, he lunched with bankers on Wall Street, fed a Bengal tiger at the Bronx Zoo, and spoke to 30,000 people in Central Park. A New York Times editorial exclaimed, “The young man is larger than life.” By the time of Castro’s next trip, for a meeting at the U.N. General Assembly a year and a half later—after he nationalized U.S. companies, executed even more opponents, and purchased arms from the Soviet Union—the euphoria had died down.

The Japanese Car

Also in April, the New York Coliseum hosted the International Auto Show, which took up one-third more floor space than the previous year’s edition and featured cars made by 65 companies in nine foreign countries, many of them sporting, as the Times reported, “sleeker styling and more powerful engines.” For the first time, cars from Japan were on display, including Datsuns and Toyotas. Coinciding with the tanking of the Edsel—Ford Motor would halt its production seven months later—it was the first sign that Detroit could no more dominate its market than Washington could dictate to the world.

‘Sick’ Comedy

On the night of April 9, Steve Allen, host of his own prime-time variety show on NBC-TV, introduced his first guest of the evening: “Ladies and gentlemen, here is the very shocking comedian, the most shocking comedian of our time … Lenny Bruce!” The very appearance of this “sick comic” on national television was a sign that something in the air was changing. Where most of the era’s comedians told jokes about wives, kids, and mothers-in-law, Bruce uncorked elaborate monologues about sex, drugs, politics, and the hypocrisy of organized religion—topics nobody was supposed to mention in “mixed company,” much less on a public stage.

The Birth of Racial Politics

In July, Mike Wallace hosted a two-and-a-half-hour nationally syndicated documentary called The Hate That Hate Produced—the first mass-media report about, as Wallace put it, “a call for black supremacy among a small but growing segment of the American Negro population,” led by Elijah Muhammad’s Nation of Islam and especially the charismatic minister of its New York chapter, Malcolm X. Their words, about the coming race war between the “divine” black man and the “evil” white man, terrified millions of white viewers but delighted a large number of black ones. Malcolm X emerged as a national leader, offering a radical alternative to the mainstream civil-rights figures of the day, including Martin Luther King Jr., who a few months earlier had traveled to India, where he embraced the tactics of civil disobedience. The tension between these two strands—militant separatism versus nonviolent protest for integration—would define racial politics in late-twentieth-century America.

Change (But Not Enough of It)

Just before midnight on August 25, Miles Davis was nearing the end of a two-week gig at Birdland to celebrate the release of his new album, Kind of Blue. It would become the best-selling jazz album of all time—and the spearhead of an artistic revolution. Mainstream modern jazz had been structured on chord progressions; Davis’s new music was built around scales instead of chords: You could do anything as long as you stayed in key. On this night, between sets, Davis escorted a young white woman to a taxi and paused on the sidewalk to light a cigarette. A cop told him to move along. Davis replied, in his defiant hoarse voice, “I work here” and, pointing to the club’s marquee, “That’s my name up there.” A plainclothes cop, misreading the exchange, rushed over and beat the trumpeter over the head with his blackjack—“like a tom-tom,” as Davis later put it. The two cops cuffed and jailed him; he was released on $1,000 bail, and doctors had to sew five stitches in his head. That summer, Miles Davis was rich and famous, the dark prince of cool. But to a couple of white cops—not in the Deep South but in midtown Manhattan—he was just another uppity Negro.

Art-Ins

On October 4, at the Reuben Gallery, a bearded artist-philosopher named Allan Kaprow staged the first of many Happenings, which he defined as “events that, put simply, happen” and that involve the audience not merely as observers but as fellow artists in the spectacle. For a few years, Happenings were the rage and came to be reflected in the love-in, the be-in, the collective acid trip, the riot—the caricature of the sixties’ most dark and frothy incarnations. Later, the spread of cell phones and the Internet sparked a revival in the form of “flash mobs” and “smart mobs”: Happenings for the cyber-century.

A New Form of Fame

On October 21, the Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum opened, looking like nothing else around it, and maybe nothing else in the world. Frank Lloyd Wright modeled the building after the ancient ziggurats of Mesopotamia. Critics likened it to an upside-down cupcake. But visitors flocked to the place as they had to no other art museum. The design might never have gone beyond blueprints were it not for Robert Moses, Wright’s distant cousin. “Damn it,” he told the Buildings Department, “get a permit for Frank, I don’t care how many laws you have to break.” Sol Guggenheim had collected Old Masters until he fell for the Baroness Hildegard Rebay von Ehrenwiesen, a surrealist artist half his age who turned his head to “nonobjective art”—paintings by Kandinsky, Klee, Léger, and herself. A museum of these works, she told Sol, would serve as “a temple to the spirit.” Wright also wanted to create a temple, but to the primacy of architecture—“the Mother-art,” he once said, “of which Painting is but a daughter.” Ada Louise Huxtable called it “less a museum than it is a monument to Frank Lloyd Wright,” and it spawned the age of the superstar architect.

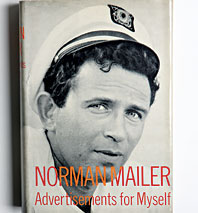

Mailer’s Recovery

On October 30, Norman Mailer’s Advertisements for Myself hit bookstores, marking a bold new step in the author’s career and a new literary genre—the New Journalism—that would transform American writing: a compilation of his short stories, essays, and blunt commentaries, interspersed with prefaces on how he came to write the pieces and retrospective appraisals of their merits, often reprinting the most blistering judgments by others. It had been a dozen years since Mailer wrote The Naked and the Dead, hailed as the finest novel to come out of World War II. In the interim, he’d written two novels that didn’t fare so well, fallen into a fit of depression, discovered the magical combo of jazz and marijuana, and reemerged, keen to cultivate an image as a “psychic outlaw” of his time, the “philosopher of Hip.” He wrote that he detected “the hints, the clues, the whispers of a new time coming … a universal rebellion in the air,” in which “the frantic search for potent Change may break into the open with all its violence, its confusion, its ugliness and horror, and yet … there is a beauty beneath.” This book—with its links between nihilistic hipsters and the omnipresent A-bomb—lit the fuse.

The First Indie

On November 11, Amos Vogel’s Cinema 16 club screened Shadows, a new film by John Cassavetes. Inspired by the Italian neorealists, Cassavetes used a semi-improvised script about an interracial romance and a group of young men who talk in jazz lingo and carouse around the city (a sort of Beat version of Fellini’s I Vitelloni) and filmed it in Times Square, Central Park, and the MoMA sculpture garden—all without permits. It was, in effect, the first American “indie” film. When Martin Scorsese saw it at NYU, it made him realize that “cinema could be made anywhere.”

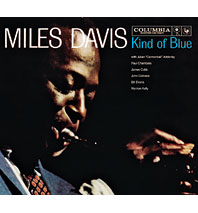

Freed Jazz

On November 17, hundreds of New Yorkers lined up in the cold outside the Five Spot, a small, dank jazz club in the Bowery, to hear an alto saxophonist who had been hyped for months as the harbinger of a new wave, the next Charlie “Bird” Parker, a 29-year-old with the strange name of Ornette Coleman. If Miles Davis had caused a stir with an album built on scales instead of chord changes, Coleman’s music—which he played on a white plastic horn in a tone that struck many as a yelp or a moan—had no apparent structure. Yet it was exhilarating, emotionally intense, ripe with a haunting beauty. Each player in his pianoless quartet seemed to go in separate ways, but they all shifted on cue, it all held together. That night marked the birth of “free jazz,” or, as the album that would come out soon after was called, The Shape of Jazz to Come. Charles Mingus, who would run hot and cold on Coleman for the next twenty years, came away with this key insight: “I’m not saying that everybody’s going to have to play like Coleman, but they’re going to have to stop copying Bird.”

This article is adapted from the book 1959: The Year Everything Changed, by Fred Kaplan (out this month from Wiley). © Fred Kaplan.