The official residence of the Roman Catholic Archdiocese of New York, a mini-mansion improbably nestled behind the main sanctuary of St. Patrick’s Cathedral, is decorated largely in early Masterpiece Theatre style—thick red carpet, deep oak paneling, gilded frames, priceless antiques. Here, in the middle of midtown, everything is beautifully still. You can hear the grandfather clock ticking from the next room. A uniformed butler serves a glass of water on a gold-rimmed plate atop a sterling-silver platter.

Then, down the staircase bounds New York’s new archbishop, Timothy Dolan, red-faced and boisterous, who succeeded Cardinal Edward Egan in the post in April. “You want coffee? You want anything in it?” He is a glad-hander and a backslapper, a tall, energetic, portly Irish-Catholic lug who likes smoking cigars and sipping Jameson’s. He makes a point of saying he’d be far happier talking to me at a parish fish fry than here, jamming himself sideways into an ornate, narrow chair. And before long, Dolan is eagerly discussing some of the more controversial issues he’ll have to weigh in on—like gay marriage, blocked during the last legislative session in Albany but almost certain to be reintroduced. As early as his first week, he went on record saying he believed the union between a man and a woman was “hardwired” into us. Now, with a smile, he anticipates the question of where that leaves gay men and lesbians. “Do I hear you saying, ‘Well, if something’s hardwired into us, wouldn’t it be hardwired into them?’ ” he asks.

There is a narrow range of responses that contemporary Catholic leaders have made to a question like this—ranging from a 2006 conference of American bishops concluding that “homosexual acts … violate the true purpose of sexuality,” to the 1990 Catholic Encyclopedia’s declaration that being gay is “not a normal condition, the acts being against nature are objectively wrong.” Dolan goes in another direction. “I would say likewise hardwired into us is the desire for friendship and a desire for companionship,” he says. “And I think the church would say, ‘We must respect that.’ So we would not take that away from anybody, whatever their sexual preferences might be.”

Friendships of the sort that Dolan is describing—leaving aside any sexual component—are all right in his eyes, he explains, as long as they aren’t called a marriage. “We’re more into the defense of marriage itself,” he explains, “so that even though people would have the right to companionship, the right to marriage would only be, by its very definition, between a man and a woman.”

But now Dolan senses that he may have said something disappointing. So he strikes a conciliatory note. “It’s not that we’re saying, ‘You don’t have the right.’ We would say that if people feel that the concomitant rights of friendship and companionship are being violated—for instance, insurance coverage, or the ability of one to visit a sick partner—we would defend those rights. There are ways to ameliorate some of the disadvantages that same-sex couples feel without tampering with the very definition of marriage.”

That, I say, sounds a lot like domestic partnerships.

Dolan straightens up suddenly. “It does sound like that,” he says. “And thank you for pointing that out. Because I wouldn’t want to go there.”

It can’t be easy being leader of the Roman Catholic Archdiocese of New York—expected to play creative defense on every issue that offends the sensibilities of the church, in a city closer to Sodom than to Eden. Yet there may be no religious posting in the United States as prominent or powerful, even today. True, much of the job, which involves serving some 3 million Catholics in 400 parishes from Staten Island to the Catskills, is administrative and ceremonial: There are budgets to balance, schools to run, Masses to lead. Nor is New York the largest American archdiocese; that honor goes to Los Angeles. Even so, the New York position is akin to being American pope. From their pulpits here, Cardinals Francis Joseph Spellman and Terence James Cooke shaped the national discourse. Spellman, who served 28 years, was a virulent anti-Communist and supporter of the Vietnam War; Cooke, who succeeded him in 1968, implemented more-progressive Vatican II reforms. The model of a modern New York cardinal, of course, was John Joseph O’Connor, who sparred jovially with Ed Koch and spoke out against abortion and for the rights of immigrants and the homeless. A polarizing figure, O’Connor nonetheless carved out space in the public sphere for a conversation about morality. He also brought a sense of excitement to the Catholic experience here, helping his diverse and disparate flock believe they were a part of something bigger than themselves.

In the years since O’Connor’s death in 2000, American Catholicism has entered a troubled period—marked by sex-abuse scandals, parish and parochial-school closings, and a dire shortage of new priests. Egan, O’Connor’s successor, was in large part an embattled, defensive, practically Nixonian figure, presiding over ugly budget cuts, avoiding comment on the sex-abuse cases, and, by the end, even alienating many of his own priests. Church attendance across the country has continued to slip, as the Vatican’s positions on social issues seem more and more out of step with those of contemporary American culture. Today, a growing number of Catholics in the U.S. are openly campaigning to let priests marry; to have women assume leadership roles; to foster more acceptance of gay men and lesbians. Our pro-choice president was even invited to speak at the University of Notre Dame. Catholic leaders across America are now faced with the same dilemma: How do you maintain the message of the church when that message is being questioned with ever-greater frequency? In choosing Timothy Dolan for the critical New York post, Rome has picked someone who is, if nothing else, an expert message-deliverer, blending the spotlight-loving tendencies of an O’Connor with all of the warmth and approachability that Egan lacked. But if you can’t alter the content of the message, is the delivery enough?

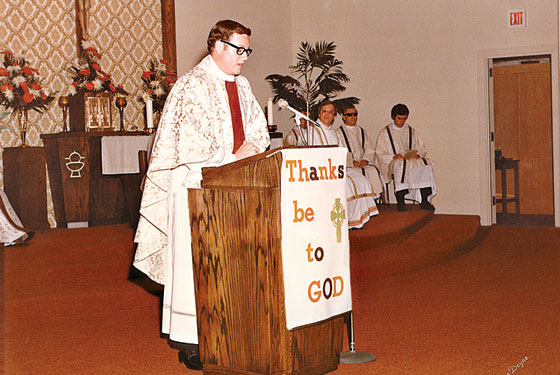

In the middle of one of his first homilies at St. Patrick’s last spring, Dolan told a story about a precious set of rosary beads, bestowed upon him by Pope Paul VI as a gift for his parents—“to thank them for giving their son to the church.” His mother, Dolan explained, keeps those beads safely inside her purse to this very day—“right,” he added with a glint in his eye, “on top of her lottery tickets.” It took a while for the laughter to die down.

His entire career, Dolan, 59, has approached the job of being a priest not as a daunting paterfamilias but as that heckuva-nice-guy you meet at some wedding who turns out to be a priest. He is what other priests call a “lifer,” someone who found his calling early and steered a course to the seminary right after grammar school (last spring, his first-grade teacher flew in to do the reading at his installation in Manhattan). He grew up in Ballwin, Missouri, the oldest of five children. His mother still lives in the St. Louis area, but his father, an aircraft engineer, died of a heart attack, in 1977—just nine months after Dolan was ordained. “He doesn’t have to put on any kind of show,” says Monsignor Michael Curran, a Brooklyn priest who has known Dolan for two decades. “He’s very comfortable with who he is and what he’s been called to be. And he uses his personality, his human gifts, to communicate a very powerful spiritual message. Maybe a psychologist could put it better, but I think there’s probably not a trace of an identity crisis in the man.”

Sex, he says, is not a human right, even if modern culture has made it appear that way.

As a priest, Dolan found inspiration in Pope John Paul II, who had no ambivalence about engaging the world at large, expressing the joy he found in his faith rather than playing the public scold. Dolan was also quite ambitious. After studying church history at Catholic University of America in Washington, D.C. (Dolan is one of just two active Catholic bishops to have earned a Ph.D. in the subject), he served as a parish priest in St. Louis before returning to Washington to be secretary to the pope’s ambassador to the United States. Later he moved to Rome for seven years to run the school for American seminarians. His inspirational book, Priests for the Third Millennium, has become a textbook in many seminaries, and he likes to talk about how the priest’s lot is not some endless ordeal of self-denial. “True freedom is the liberty to do whatever we ought, not the freedom to do whatever we want,” he has said. “We are at our best when we give away freely what’s most inside of us.”

In 2001, Dolan was summoned back from Rome to become the auxiliary bishop in the St. Louis archdiocese, where he was put in charge of responding to the sex-abuse scandals there. Then, a year later, came the call to become archbishop of the Milwaukee archdiocese in the wake of a very public scandal: Rembert Weakland, a liberal mainstay for more than twenty years, had stepped down as archbishop after it was revealed that he had paid $450,000 in 1998 to silence a man with whom he’d once had an affair.

The Weakland situation alone would have been difficult, but fund-raising was in tatters and church attendance was way off, as was enrollment at the seminary. Dolan seemed undaunted. “Are we going to retreat to the bunkers,” he said, “or are we going to go to the housetops?” He convened a meeting of sex-abuse victims, mental-health professionals, law-enforcement officers, and church hierarchy—and even published the names of some offending priests. (Cardinal Egan never did anything remotely this conciliatory.) Under Dolan, the archdiocese also paid out $26.5 million in sex-abuse cases, settling with more than 170 people.

But then he retrenched. Dolan balked at removing all known sex offenders from the ministry, according to some critics, failing to fully publicize direct admissions of guilt from clergy child rapists. And, victims charge, he even let some clerical offenders keep their jobs. (“There was a certain vociferous segment that would be unhappy with anything that we did,” Dolan says now.) He also rallied the base by steadfastly resisting calls for reform. He silenced one priest who entertained the idea of ordaining women and shut down a large group of priests who wanted to discuss making celibacy optional. By the time he left Milwaukee, his capital campaign had raised only about half of the $105 million he’d hoped, and he was forced to close more than twenty parishes.

Where Dolan made the most progress, however, was in public relations. During Milwaukee’s darkest hour, he put on a foam cheese-head during a Mass and made jokes about having to upgrade from Bud to Miller. Those who watched him closely believe it was his populist charm that impressed the Vatican enough to bring him to New York—beating out more-experienced bishops, as well as those who might have been better suited to the growing Latino population. (Dolan does not speak fluent Spanish, though he spent three weeks in an immersion class this past summer.) For as contemporary as he sometimes seems, he is also, in many ways, a throwback choice to lead New York: Irish, conservative. “Dolan is part of this hope that a return to orthodoxy—the fighting seminarian with the crew cut and the fifties values—will be what’s going to change things for the church,” says Peter Isely, midwestern director of the Survivors Network of Those Abused by Priests. Yet any hard-line posture he might take is expressed so cheerfully, so gregariously, that his mere presence seems like a welcome change. “Well, I think people are just gonna love you,” YES Network announcer John Sterling said when Dolan popped by the broadcast booth on the Yankees’ opening day. “You are such a people person.” “Well, thank you!” Dolan said with a chuckle.

Dolan admits that he was intimidated by the move to New York; it helped that he didn’t have a choice. He was told he was being transferred, as if he were in the military. When he got the news, he thought back to the day he’d learned he was going to lead the Milwaukee archdiocese. “Of course, I told my mother,” Dolan says. “And she said, ‘Well, Tim, how do you feel?’ And I said, ‘Well, I’m kinda scared. I really don’t know if I’m the man for the job.’ And she said, ‘Well, apparently people that know you better than you know yourself think you are, so just be yourself. They must like what they see.’

“And I thought, ‘Wow!’ ” Dolan says, letting out a huge belly laugh. “ ‘I guess you’re right, Mom. Thanks! Give me another piece of pie!’ ”

Before he arrived, Dolan made a study of the archbishops of New York, and the “dual tug” of the job. “You might use the Latin,” he says. “Ad intra is that [which is] internal, ad extra would be that outside. Sometimes the bishop will shine in one or the other. For instance, Cardinal O’Connor and Cardinal Spellman seemed to shine on the ad extra. Cardinal Egan by his own admission shined ad intra. Cardinal Cooke seemed to be brilliant in kind of combining both.” Asked which role he’ll veer toward, Dolan demurs: “That wouldn’t be a strategic decision that I would make.”

But it’s clearly the ad extra that intrigues him. The challenge, as Dolan sees it, is how to expand the church’s appeal while protecting its principles. “How do we make something that is by its nature timeless timely?” he asks. “How do we make something that is by its nature otherworldly attractive to the world?”

What he is too diplomatic to say, perhaps, is that he has inherited an archdiocese shell-shocked by the nine-year era of his ad intra predecessor, Egan. Dolan has already benefited greatly by comparison. “I don’t want to compare, but in many ways he’s like Barack Obama,” says Father John Duffell, an Upper West Side priest long thought of as a leader of Egan’s loyal opposition. “He’s okay in his own skin. And he likes the priests, which is a big thing.” As with Obama, expectations are high. “Everyone wants everything to happen at once,” Duffell says. “There’s need for leadership on immigration, housing, poverty, injustice.”

The priests are waiting for him to address some controversial issues, among them the possibility of more parish closings. Dolan already has rebuffed former parishioners of Our Lady Queen of Angels in East Harlem, in a letter that refused to re-evaluate Egan’s decision to close the parish. Yet he seems focused on altering the way parish closings are perceived. “You obviously want to stay away from the word closing,” he says, “because that’s not your goal. It’s to assess—are we using our resources and our temporal properties to our best ability? We’re still predicated on the fifties model that a Catholic person always feels allied to a parish because it’s where he or she lives. That ain’t true anymore. They float.”

Dolan has worked hard not to attract controversy in his first few months. When he has emerged in public, it’s been mostly to do things like bless the extension tunnel of the 7 subway line. He explains this by saying that he needs time to get used to the size of the job: “Sometimes I find my head just spinning with, ‘My Lord, how am I gonna get to 410 parishes? How am I gonna get back to this woman who just asked me to pray for her little child, who’s with cancer?’ ” This month, he’ll be returning to leading Mass at St. Patrick’s most weekday mornings as well as Sundays, just as Cardinal O’Connor did. Egan used that time to visit parishes, but Dolan will save that for Sunday afternoons. “Any parish that has a chicken dinner,” he says. “If you want to put the word out there, they’ll know how to get me: chicken and dumplings.”

In private, though, he’s already impressed New York’s political class. “He’s very much in the mold of John Cardinal O’Connor,” says Ed Koch. “He’s a guy who I have concluded is fearless and outspoken—aware of the power and majesty of the role. I like Cardinal Egan, but he was a more withdrawn figure. I believe there’s been no one since John Cardinal O’Connor who has had a major public role on behalf of the Catholic Church. That’s gonna change.”

When talking about repairing the church’s reputation, Dolan describes two competing schools of thought within Catholicism—“an ongoing conversation on whether or not we are the church of the catacombs or whether we’re the church of the marketplace.” It’s a debate that ran all the way up the Vatican. “Ratzinger and Wojtyła would spend a lot of time arguing about that,” he says. “They said that Ratzinger,” who became Pope Benedict XVI, “would be more about the church of the catacombs, and if we lose people, so what? Because he used to love to quote, ‘It’s when you prune that you have growth.’ And Wojtyła”—Pope John Paul II—“would say, ‘Joseph, my brother, no. Are we not best when we stand high and stand tall and try to be a light to the world and salt to the earth?’ ” Dolan suggests that even Benedict has done more to embrace the secular world than anyone had expected. He once heard Benedict say, “The church is all about yes, yes, not no, no.” “And I thought, Bingo! You know, the church is the one who dreams, the church is the one who constantly has the vision, the church is the one that’s constantly saying ‘Yes!’ to everything that life and love and sexuality and marriage and belief and freedom and human dignity—everything that that stands for, the church is giving one big resounding ‘Yes!’ The church founded the universities, the church was the patron of the arts, the scientists were all committed Catholics. And that’s what we have to recapture: the kind of exhilarating, freeing aspect. I mean, it wasn’t Ronald Reagan who brought down the Berlin Wall. It was Karol Wojtyła. I didn’t make that up: Mikhail Gorbachev said that.”

“God made me with a particular soft spot in my heart for a martini.”

“I guess one of the things that frustrates me pastorally,” he adds, “is that there’s this caricature of the church—of being this oppressive, patriarchal, medieval, out-of-touch naysayer—where the opposite is true.”

That said, the church must say no when to do otherwise would be to threaten its very identity. There simply can’t be compromise on some issues—like abortion—no matter how nuanced or compassionate the conversation is around them. Suppose a pregnant woman were to come to Dolan and say “I’m thinking of having an abortion.”

“I wouldn’t get argumentative,” he says. “But I would say, ‘Well, you’re kind enough to ask me. So what I think I hear you say is what guidance and enlightenment can I give.’ Would I be a bully about it? In no way whatsoever. I would hope I would come across as tender, as compassionate as possible, but that wouldn’t lessen the cogency of my saying ‘Please don’t do this. We’re talking about an innocent life here. What can I do to help you make the decision to keep your baby?’ ”

And this is true with cases of rape and incest as well, I ask?

“Yeah,” he replies.

Then there is the clergy sex-abuse issue. Dolan has been laudably frank about the damage inflicted on so many Catholics. “We’ve got a lot of credibility to regain,” he said shortly after he arrived in New York. “And we’ve still got a lot of victims, survivors, and their families out there who are hurting big-time.” But he also fully supported the work of the archdiocese’s lobbying arm to sideline two bills in Albany that would have rolled back the statute of limitations and allowed more alleged abuse victims to make their claims in court. (A version of one or both of those bills might return in the next session.) “I don’t think it’s any accident that once he showed up in New York, the lobbying became more bare-knuckled and political,” says Marci Hamilton of Cardozo law school, a critic of the church’s role in abuse legislation.

“There’s a perception out there that the Catholic Church has deep pockets,” Dolan responds. “That’s what we were worried about, that the Catholic Church is being unfairly targeted.” He also argues that the notion of the church as a hotbed of abuse is outdated: “Nobody is handling [the problem] more aggressively. And I don’t think society gives us credit for that.”

Then, of course, there is gay marriage. Dolan stands to become cardinal soon, and by the time his tenure here ends, which may not be for decades, it’s quite possible that something like half of the states in the union will have legalized same-sex marriage—New York surely among them. Dolan explains the church’s intractable position on this issue by describing homosexuality as a compulsion that should be controlled, much the same way as premarital sex should be. Forget about gay and straight sex; both are wrong, he says, simply because they take place outside the confines of marriage.

“If you have been gay your whole life and feel that that’s the way God made you, God bless you,” Dolan says. “But I would still say that that doesn’t mean you should act on that. I would happen to say, for instance, that God made me with a pretty short temper. Now, I still think God loves me, but I can’t act on that. I would think that God made me with a particular soft spot in my heart for a martini. Now, I’d better be careful about that.”

So, I ask, is being gay a character flaw?

“Yeah, it would be,” Dolan says—his smile broadening. “And we are all born with certain character flaws, aren’t we?”

But this leaves gay men and lesbians no choice but to form sexual partnerships that will always be seen as sinful. Isn’t that unfair?

Dolan takes a moment to think this over. “There’s no option,” he agrees, still smiling. “But I don’t know if that’s unfairness.”

Sex, he goes on to say, is not a human right, even if modern culture has made it appear that way. But this, he adds, is actually good news. His eyes light up. He seems excited—both by what he’s saying and by the fresh way he’s found to say it.

“The church—this hopeless romantic that she is—holds that sexual love is so exalted that it is the very mirror of the passion and the intimate excitement that God has for us and our relationship. We actually believe that when a man and a woman say ‘I do’ forever, that our love will be faithful, forever freeing, liberating, life-giving. We believe they mean it and they can do it! That’s exciting, that’s enriching, that’s ennobling. That’s a big, fat yes—yes!”