When Thomas Jefferson visited the “Unquachog Indians,” in June 1791, he noted that the tribe “constitute the Pufspatock Settlement in the town of Brookhaven, South Side of Long Island.” The settlement was conveniently located in the backyard of his friend William Floyd’s plantation, where Jefferson and his longtime wingman James Madison happened to be crashing. Jefferson made an effort to document the language of the tribe, many of whose members tilled his host’s fields: “Cow … Cowsen; Horse … Hofses; Sheep … Sheeps; to cut with an axe … poquetahaman; handsome … worecco; ugly … nechowuchayuk.” He concluded: “There remain but three persons of this tribe who can speak its language: They are old women, from two of these, brought together, this vocabulary was taken, a young woman of the same tribe was also present who knew something of the language.”

Harry Wallace, the current chief of the Unkechaug Indian Nation, trying to learn at least an approximation of his native tongue, has an Algonquian-language app on his iPhone. “I’m gettin’ there,” he said from behind a large cluttered desk in his office, a small cedar-paneled lodge set behind Poospatuck Smoke Shop and Trading Company in Mastic, Long Island. It was early August; 65 miles away on Manhattan Island, Mike Bloomberg—modern-day equivalent of the Great White Father—was not happy with Chief Wallace and the Unkechaug. This is because the chief and his tribe were making big bucks selling millions of packs of cigarettes tax-free, many of these to residents of New York City, which imposes a $1.50-per-pack tax of its own. Exactly how many New Yorkers were getting smokes under cover of the Unkechaug is not easy to answer. An Independent Budget Office report estimated that in 2006, around 207 million packs were bought by city smokers. No tax was paid on a quarter of these (only a fraction of the untaxed smokes were bought on Indian reservations). But Bloomberg has declared war on smoking, and wherever there is smoke, he wants his cut. So last September, the city filed a motion in federal court against a group of Unkechaug retailers, claiming hundreds of millions in lost city tax revenue.

Wallace was still recovering from last night’s “sweat”—several important dudes, dome-shaped lodge, a pit of hot rocks in the middle, much perspiration, a prayer song or two—at an undisclosed location. It was the culmination of a week of mourning for Benny Miller, a 22-year-old tribe member who died in a motorcycle accident. His death mobilized Unkechaug near and far to return to the reservation, to mourn and sing: the honor song during the wake, the various burial and prayer songs throughout.

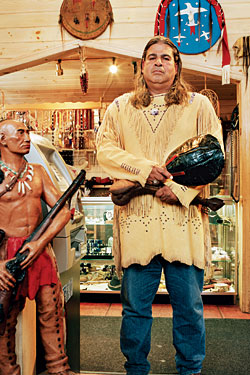

Geronimo’s refrain, “They’re not satisfied until they get all of it,” is never far from Chief Wallace’s mind. But signals were still pointing toward victory for the Unkechaug: Only weeks prior, a New York State Appellate Court ruled that the Cayuga Indian Nation could continue selling untaxed cigarettes to non-Indians. He pushed a button on a speakerphone connected to the smoke shop. “Can I get two cups of coffee in here?” he said in a baritone. The chief is 55, broad-shouldered, and has long thick salt-and-pepper hair, which he wears in a tight ponytail. Various New York State Bar plaques line the walls. It was Wallace who opened the first smoke shop back in 1991, with the intention of making a little money, sure, but as a declaration too—the Unkechaug’s sovereign right to exploit whatever economic advantages the Indians’ sovereignty affords.

The Unkechaugs, like all recognized tribes, are exempt from state and many federal taxes, but beyond this their economic status is murkier, based on whatever arrangement the state and the Indians can agree on. In 1994, the U.S. Supreme Court ruled that New York is entitled to collect taxes on Indian sales of cigarettes and motor fuel to non-Indians. Coming up with a way of enforcing that tax has been the trouble.

Their tribal rights have been questioned before, in various ways. Among the papers on the chief’s cluttered desk was a folded-up family tree. In 2006, Gristedes Food Inc. filed a suit—almost all of it since dismissed—questioning the legitimacy of the residents’ native heritage. Gristedes claimed that Unkechaug vendors, located some 65 miles from their nearest supermarket, were unfairly cutting into their profits. Fortunately, the tribe keeps excellent records. The first time such an accusation was made was back in 1935, when publishing scion and notorious cad William Shepherd Dana bought the Floyd estate and claimed that the tribe were, essentially, squatters.

The chief laid out the genealogy for me. “So you start with me, Harry Wallace,” he said, consulting the family tree before him. “Then it went to my mother, Lydia Anne Davis, and then it went to her parents, Charles Davis and Lydia Anne Davis. My grandmother has the same name.” He paused and looked up over his reading glasses, then rattled through a few more names. “Now, Sylvie Hicks and Jerusha Lott were sisters. Their mother was Sybel Lott, and Sybel Lott—we have historical documents—was from a very prominent Indian family.” She was a direct descendant of Chief Nowedonah, and Wallace believes it’s a good bet she was one of the elderly women Jefferson spoke to.

“Up until recently, the role of chief was more of a spokesperson and a leader in ceremonies, in powwows and June meetings and such,” Wallace said. But that was before the cigarette trade, which has burgeoned as the taxes charged by the state and the city—$2.75 per pack to the state; $1.50 to the city—have driven people to stock up on tax-free Camel Lights in Poospatuck country.

Along with revenue, the cigarette business has also occasioned crime, something Bloomberg has been at pains to highlight. In 1997, in a meeting of the tribal council to discuss a $.25-per-pack levy on smoke shops, three men in masks barged in, brandishing firearms, pointing them at the chief’s head.

In the next few years, a man named Rodney Morrison, not an Unkechaug himself but married to one, was charged with firebombing the car of a rival smoke-shop proprietor and the murder of another. Though he was acquitted of those charges, in 2004 he was arrested (and eventually convicted) of a racketeering conspiracy involving black-market cigarettes.

The State Department of Taxation and Finance says that in 2007, 11.3 million cartons changed hands on the reservation. That’s more than 25 times the number reported a decade before, and, if the numbers are correct (the chief says they are not), over $11 million in revenue for the tribal council—not a bad return on 55 acres in Mastic.

Chief Wallace took a cigarette from a pack of Nat Sherman New York Cut, sank back in his chair, and provided a different economic narrative. “Here’s one that got $1,000. Whoa, this one’s a star, she got $1,300,” he said, reading off the names of reservation students who would be receiving gift certificates for their academic performance the previous school year. There is also a modest reward for attendance. In the past year, the tribe has spent $200,000 on education, paying 25 percent of tuition for the 40 Unkechaug students currently enrolled in colleges around the country.

After a while, we climbed into his red Cadillac. “The only thing you need from the white man is a car, because a car is faster than a horse,” he said. Driving through the reservation: It’s hard to see beyond the smoke shops to take in whatever natural beauty exists on the river banks. Neon signs offer competitive prices, creating tough decisions for customers to contemplate from pickup trucks whose idling engines are joined by the buzz of the renegade ATVs giddily weaving about the traffic, as if to remind you, in case you happened to forget: You’re in Indian country now.

“The goal here is not to stop us from selling cigarettes,” Chief Wallace said. “It’s to try and destroy us as a people.”

The settlement, located in the hamlet of Mastic, a few miles west of Westhampton, between Carmans River and the Forge River, was once an ideal location for hunting right whales. According to historian John A. Strong, of Long Island University, the Unkechaug were famous for their skill at whaling. Don’t get the chief started on the whaling business. Sovereignty, his wounded knee! “In 1676, our people attempted to establish their own independent whaling company,” he began. “We had the best whalers. We decided to gather up all of our skilled harpoonists and whalers and formulate our own company. There’s a documented history of complaint to the colonial governor of New York that the settlers in the towns were interfering with our company, trying to take away whales that we captured, destroy our boats. All these things were in an effort to prevent us from establishing an independent, economically viable enterprise. Sixteen-seventy-six. How many years ago was that?”

Harry Wallace grew up in Queens, but made regular visits to his uncle on the reservation, which was in bad shape at that time; a 1967 government report concluded that the living conditions were worse than those of migrant farmworkers in California. Harry ended up at Dartmouth—the first in his family to attend college. The first day he got there, some football player started calling him names. Harry knocked him silly. “He messed with the wrong guy,” he said. The football team, as well as other sports teams, were known as the Dartmouth Indians, but Wallace led a successful campaign to change the name—now the teams are known as Big Green. After Dartmouth, Wallace attended New York Law School. He spent the eighties as an attorney in Manhattan, working on things like personal injury, landlord-tenant disputes. But there was work to do on the reservation.

There is no landlord, per se, on the 55 acres between Eleanor Avenue and Poospatuck Lane—it’s communal property owned by the tribe, not any individual. What land is left cannot be sold. But residents aren’t able to use their land as an asset to get a loan, to fix that leaky roof. And sovereignty also means responsibility for your own municipalities: telephone poles, road maintenance, running water are provided for largely by the tribe itself.

What began in 1700 as a deed for 175 acres had already been reduced by the time Jefferson visited to the slice it occupies today. Most of the land was lost in 1730, when the Indians handed over 100 acres “in consideration of twenty Dutch blankets, four barrels of cider, and a sum of three pounds [of wampum].”

Thus the scene at Squaw Lane, which is the tribe’s main source of revenue. The street is chockablock with smoke shops with pastel vinyl awnings: Geronimo’s, Tammy’s, Princess Rainbow Smoke Shop, the Peace Pipe Smoke Shop. “All of these buildings here have been impacted in a positive way by the business,” Wallace said, pointing out some of the over 80 homes that have been renovated or replaced—modular for mobile—in the last year. “The real story is what’s happening, the transformation of what’s happening in this community.”

Mayor Bloomberg, along with Representative Peter King, wrote an August 4, 2008, editorial arguing that cigarette sales on reservations should be taxed—one line insinuated that cigarette-smuggling money might go to terrorists. Chief Wallace is still riled about it. “We got blamed for the MTA deficit! Phenomenal, man. Supporting terrorism. It upsets me because this is our land, whether we occupy it or not. It’s still our land, and we defend our homeland against all enemies, domestic and foreign.”

On August 25 of this year, a federal-court judge in Brooklyn handed down a verdict addressing the Unkechaug’s motion to dismiss. Federal Judge Carol Amon denied the motion and ruled that the state appellate court had misinterpreted the law in question. She ruled that regular tax law indeed applied to the tobacco trade on Indian reservations, as it does everywhere in the state. She issued a temporary injunction banning all further cigarette sales at four stores identified in the city’s suit. Chief Wallace and the Unkechaug appealed. On September 25, the court announced that though the appeal would be heard, the injunction would continue. But that leaves ten other smoke shops in the Poospatuck reservation, and the cars are still backed up around Squaw Lane. “The city will go after every dollar that is owed to city taxpayers,” said Bloomberg in a statement.

Wallace is far from ready to smoke the peace pipe, however. He says it’s the same as it was with whaling in the seventeenth century. “The goal here is not to stop us from selling cigarettes,” Chief Wallace said. “It’s to try and destroy us as a people, because every effort that we made to resolve these things has met with resistance. They don’t want to do it. They want to take it as far as they can to try and kill us.

“They need a scapegoat for not blaming his friends on Wall Street,” said the chief, his tone slowly rising. He began pacing in circles, literally hopping mad. “Who is a convenient scapegoat? The smallest tribe in New York, selling a demonic product—that’s a good scapegoat.”