In the sleepy, refined little towns along the Metro-North line where everyone knows everyone, Annie Morell Petrillo and her sister, Alex Morell, had been notorious for years. They were the Scripps girls, carefree and lovely children of privilege whose divorced mother had married a much younger man—a housepainter named Scott Douglas with a secret history of womanizing, alcoholism, and depression. Anne Scripps Douglas, a 42-year-old heiress to the Scripps-family newspaper fortune, had been living off a trust fund that Scott desperately wanted to control. On New Year’s Eve in 1993, Scott beat Anne in the head at least a half-dozen times with the claw end of a hammer. Then he drove to the center span of the Tappan Zee Bridge, pulled over, and jumped to his death.

Some fifteen years later, on a warm Thursday last fall, Annie Morell Petrillo awoke and set about her usual regimen of distracting herself. Mornings weren’t typically a problem. Although Annie, 38, lived alone in her two-bedroom condominium in Rye Brook—her 13-year-old son, Michael, stayed with his father most of the week—she would manage to busy herself with errands, hopping into her black BMW SUV and popping into Kohl’s or CVS. For lunch, her sister, Alex, who lived one town over, would often pick up the check at someplace Annie could no longer afford. But it was at night that Annie was most vulnerable. That was when she’d call friends to keep her company as she walked her dogs. Sometimes she’d call in tears, talking about how she couldn’t find a man to love or how she missed her mother. On nights when she’d had too much to drink, she would make calls that were bitter, angry, even vicious—calls she’d have no memory of the next day.

After lunch together at the Town Dock Tavern that day, Annie and Alex went on to get manicures and pedicures in the village. They were more like twins than just sisters. Both were divorced moms, tan and curvy and bawdy, their smoky, throaty laughs filling the room. Alex stayed with Annie most of the afternoon, and a few friends dropped by. But Alex left to go home for dinner, and by 6 p.m., Annie was home by herself.

She went on Facebook, sending a quick message to her friend Rosey Kalayjian: “What’s up, hooka! Haha, miss you!” Then, at 7:30 p.m., Annie called her friend and sometime boyfriend, Chris Smith, from the road. Her signal was breaking up. She said something about being at the Mobil Station in Rye Brook to get cigarettes. The signal was always bad there, so Smith didn’t give it a second thought.

Fifteen minutes later, just after 7:45 P.M., Annie’s vehicle came to a stop in the center span of the Tappan Zee Bridge. Under the bright lights, at least a few stalled, startled drivers had a clear view of a beautiful woman emerging from her car and walking purposefully to the bridge’s rail. At 7:49 P.M., Annie dialed Smith again. She stepped to practically the exact same spot that Scott Douglas had jumped from fifteen years earlier. Smith heard a loud swooshing sound, then nothing.

Alexandra Morell is smoking on the porch of a friend’s house in Rye, looking out over the Westchester Country Club. She is trying to make sense of her sister’s death—at the same age as her stepfather, slipping out of the same make of car, leaping from the same spot. On Alex’s left wrist is a tattoo of her mother’s and father’s initials, arranged crossword style, sharing the letter M for Morell. (Her mother’s second married name, Douglas, is omitted.) “In school,” she says, “they taught me they thought there was a vein from here to my heart. So now that goes over that vein.”

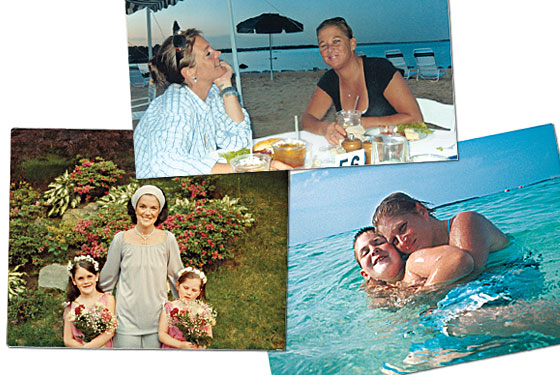

Before their mother’s murder, Alex says, she and Annie had shared an idyllic childhood on a quiet, leafy street in Bronxville, in a white-pillared fairy tale of a house with seven bedrooms—big enough for endless games of hide-and-seek, and even the occasional roller-skate through the halls. Anne Scripps Morell spent practically all her time with the two girls, making crafts, painting pictures, taking them to Baskin-Robbins. “If anything, the girls were spoiled by their mother’s love,” one friend says. “They were always with her and always expected she would be with them.” Anne was sheltered, delicate, and a little naïve—she didn’t learn to drive until she was over 40. Another friend once called Anne “the last of that generation of Stepford wives.”

Anne tended to downplay her Scripps lineage, but Annie and Alex certainly grew up wealthy. Besides the home in Bronxville, there were country-club memberships and regular trips to Scripps-family homes in Palm Beach and Grosse Pointe, Michigan. Alex was the picture-perfect girl with the daring, caustic wit. Annie was less put-together and more awkward, but warmer and more openhearted. Any toughness Annie got came from her sister. “Alex had more of a defense against feeling the drain of emotions,” says Robbie Morell, an aunt. “She may have more boundaries, so to speak.”

Their parents had married at the St. Regis in 1969 in an event that warranted a three-page spread in Town & Country. But Tony Morell, who had worked on Wall Street, was a heavy drinker, and as the couple’s marriage disintegrated, Annie and Alex were sent to the Hun School in Princeton, New Jersey. Still, Annie and Alex idealized their childhood, particularly when it came to their mother. “She was just a good-hearted person,” Alex says. “She loved, loved, loved her kids.”

Annie was a high-school junior in 1987 when she learned her parents were splitting up. Both girls sided with their mother, and when Anne met a younger man just a few months after the divorce was final, the sisters were united in their opposition.

Scott Douglas was 33, dark-haired and handsome. He ran a house-painting business out of a small apartment in Greenwich; he and Anne met at a Super Bowl party at a local pub in early 1988, just months after her divorce was finalized. Scott never mentioned the daughter he’d fathered out of wedlock—or his drinking, or his bouts of depression and time in therapy. The couple were married nine months after they met, in a hastily arranged ceremony in the Morells’ living room. The bride’s mother did not attend.

With her daughters away most of the time, Anne wanted more children, and in 1990 she and Scott had a baby girl named Victoria, or Tori, whom they doted on and whom Alex and Annie also adored. But Scott saw Alex and Annie, now off at college, as competition for Anne’s affection and money. He was a dud with the country-club set, too, passing around his business card, unable to make small talk. He spent more and more time at his old apartment and office in Greenwich, not bothering to tell the women he went out with that he was married. He’d come home drunk, throwing furniture, smashing glasses, threatening Anne.

On New Year’s Eve 1993, Anne and Scott were at home. A few days earlier, after suffering a black eye, Anne had gone to family court to seek a restraining order against Scott. (Anne had sought protection from him before—he once tried to throw her out of a moving car—but the couple would reconcile, with Scott promising to quit drinking.) But the judge Anne needed to see wasn’t there that night, and she was told to come back after the holidays.

At home, Scott decamped to his bedroom to watch TV, coming downstairs every twenty minutes or so to refill his drink. Alex was away skiing for the weekend. Annie was on Christmas break from college, and was invited to a New Year’s Eve party. Her mother was planning on staying home with Tori.

“I won’t go out if you don’t want me to,” Annie said. Anne told her daughter to go ahead. “I’ll be fine,” she said. Then she walked Annie to the door and gave her a kiss.

When Annie came home and didn’t see Scott’s car, she knew something was wrong. She knocked on the door (she’d forgotten her keys), but there was no answer. Finally, police arrived. Scott’s brother had called them at 3:50 a.m., a few hours after Scott phoned him from a gas station, apparently en route to the Tappan Zee, saying, “I’ve done something really bad this time.”

Firefighters, who had also been summoned, pulled the front door off its hinges and found Anne lying on Annie’s bed, hammer blows on either side of her head and a gaping hole in the back. She was alive, but just barely. Tori, who was hiding in her room, off to the side of the master bedroom, had clearly seen what had happened to her mother. “Why did Daddy paint Mommy?” she asked.

Police found Scott’s car abandoned in the center of the Tappan Zee, a bloodstained hammer left on the passenger seat. It took three months, until the spring thaw, for his corpse to wash ashore twelve miles away.

For fifteen years, Annie and Alex were each other’s only true reference point in dealing with their mother’s murder—who else could ever really understand?—though they differed dramatically in the way they processed it. By the time Alex saw her mother, Anne’s face was bandaged; she was in a coma. But Annie saw it all. She rode with her mother to the hospital. She watched her slip into a coma, only to die six days later. “Scott took a hammer to my mother’s head and a steak knife to her face,” Alex says. “The intrusions in her head were so big they thought they were gunshot wounds.” She shakes her head. “Imagine finding your mother like that, her head torn apart and her face all ripped up. So my poor sister Annie had to live with that. I just don’t think she ever got that image out of her head.”

Annie dealt with her grief at first by throwing herself into caring for her half-sister. “Annie became a mom to Victoria,” says an old friend, Hilary Shevlin Karmilowicz. “Everything she was going through, it was Tori, Tori, Tori. She wanted to get custody of her. But she was 22 years old.” In early spring, Anne’s sister, Mary Scripps, brought Tori to her home in Vermont and eventually adopted her. Alex understood. “We were in no state of mind to raise a child,” she says. But for Annie, even though Tori stayed in touch and visited regularly, it was another blow.

In the years that followed, a few friends of the family say, Alex dominated Annie, taking advantage of her kindness and running her life. But others say that Alex really had no choice. Her sister was deeply dependent on her, unable to be alone for long stretches without breaking down.

In 1995, Alex married the man she had been seeing at the time of the murder, a real-estate investor from Eastchester named Jimmy Romeo. In 1996, Annie, who had not returned to college after her mother’s death, married Jimmy’s best friend, Paul Petrillo, whose family owns a construction company. The couples lived fifteen minutes from one another; Annie and Paul in Eastchester, Alex and Jimmy in Rye. Alex’s daughter, Alexa, and Annie’s son, Michael, were like sister and brother—fifteen months apart in age, just like Annie and Alex. But neither marriage lasted. Alex got divorced in 1998, Annie in 2000. “It was right after my mother was murdered. We were in la-la land,” Alex says. One friend says Annie found Paul “boring,” a far cry from the fairy-tale life she craved. Another friend says Annie had drinking problems all through the marriage, and had to be hospitalized a number of times after passing out.

After her divorce, Annie moved to Rye Brook, where a number of her Morell relatives live. Annie’s tiny condo was in a wooded townhouse complex called the Arbors on the Rye Brook–Greenwich border. Alex watched as Annie’s trust fund dwindled. Their mother’s estate only seemed to have $1.3 million, far less than outsiders assumed (it’s possible the girls received other family money not mentioned in Anne’s will). In 1995, Annie, Alex, and the Scripps family sued the state family court and police for $22 million, claiming Scott should have been barred from the house in Bronxville when Anne petitioned the court on December 6, 1993, but those suits were dismissed. They also split a small sum for a USA Network TV movie about the case. Later, a source says, Annie and Alex contemplated suing their uncle James or their mother’s estate, supposedly for cutting them out of other money coming from the previous generation. “I think Mary and Jimmy were jealous because Anne was the favorite one,” the source says. The source says no court papers were ever filed. (James and Mary Scripps declined to comment for this story.)

“Imagine finding your mother with her head and face all ripped up. I don’t think Annie ever got that image out of her head.”

Annie eventually inherited more than $1 million, Alex says, but she appeared to spend it all. Even when she bought her condo, she took out a mortgage, puzzling those who thought she should have enough money to pay cash. “She basically went through everything that was left to her,” says one friend. “She just buried herself in debt.”

Shortly before her divorce, Annie had breast-enhancement surgery. “She was very small-chested,” Alex says. But Annie’s new breasts were uneven, and she was in pain. There was a second surgery to correct the first, Alex says, but that didn’t work either. In the end, “she had to have had eight or ten operations,” Alex says. “And none of that was covered by insurance. She probably spent close to $300,000 or $400,000.” One old friend of Annie’s says the surgeries may have been a form of cutting— self-abuse born of the guilt and self-loathing she felt after her mother’s murder. “Who’s going to want me now?” she’d ask Rosey Kalayjian.

Annie was eager to meet a new man and remarry. She and Kalayjian would hit the spots on Greenwich Avenue, and guys would say they looked just like Jennifer Aniston and Courteney Cox. Plenty of men asked Annie out, but nothing stuck. “She was battling so many demons,” Kalayjian says. “And to find someone who was willing to accept all of that? Plus a child—that’s another obstacle.”

To occupy herself while Mikey was in school, Annie worked part-time at the King Street Nursing Home in Rye Brook. People suspected she was trying to beat back her demons by helping others, but the move backfired. “They loved her,” Alex says, “but Annie would always get so upset whenever somebody died in the nursing home. They tell you not to get too close to the people. But Annie got close to everybody.” Annie had other jobs—an antiques-store clerk, an office cafeteria worker—but none lasted. “She was well liked and she had a great personality,” a former boss says. “But she was drinking excessively, and wouldn’t always come to work in the best shape.”

Annie’s father’s brother, George Morell, died in the September 11 attacks, and Tony himself died in 2005 of a heart attack. (Improbably, Tony’s life had been extended after Anne’s murder when he received her liver in a transplant; he’d been waiting for a match, and Alex and Annie made sure their mother’s liver went to him.) But the most difficult fresh blow for Annie came when her son went to live with his father.

Friends say Mikey was anxious about Annie’s drinking and depression. Still, “he really enjoyed being with her,” says Robbie Morell. Then, last year, Mikey began having trouble in school. When the school suggested he might have to be held back, Annie and Paul, her ex-husband, decided it would be better for him to switch school systems. Mikey moved in with Paul and did well in his new school, but Annie was lonelier than ever. “Him being gone,” a friend says, “was killing her.”

Annie told everyone she knew that she wanted normalcy. “She wanted love. She wanted to raise a family,” says Karmilowicz. Recently, she had learned that Paul’s new wife was pregnant. And when Karmilowicz told Annie she was having a fourth child, Annie groaned and said, “Why isn’t this happening to me?”

Annie drank nearly every night now. She’d drop out of contact with friends. At times, she’d mention she was taking mental-health medication, but “she thought people would be critical about it,” a friend says, “so she pushed it under the rug.” Another source says child-protective services had to place Mikey in his father’s custody on several occasions while Annie was hospitalized for alcohol use or depression.

About three years ago, Alex called Robbie Morell in a panic one morning. Annie had taken some Valium she’d ordered from the Internet. “She said, ‘I don’t know who to turn to,’ ” Robbie remembers. “I don’t know exactly how many attempts there were, but she had reached out for help lots of times.” Robbie met Alex at the Arbors and found Annie in bed. As a mental-health counselor, Robbie was compelled to bring Annie in for treatment. Annie first went to a center called Four Winds, then to Silver Hill, a facility in New Canaan where she had been once before.

At Silver Hill, the doctors recommended electroshock therapy, and Annie agreed. “It was her saying, ‘If this is something that’s going to help, I’ll try it,’ ” Robbie remembers. But when Annie came home, she forgot people’s names and things that had happened to her. “We were looking at the photo album one day and she just burst into tears and said, ‘I don’t remember that trip,’ ” says Alex. “I hate that she forgot the good times but always remembered that tragic day.”

Why had Annie so deliberately, almost gothically, chosen to mirror the method of the man who had caused her so much pain? Maybe she was saying she had died that New Year’s Eve along with her mother—that Scott Douglas, in every meaningful way, took her life, too.

Police found a note in Annie’s car. No one knows if Annie wrote it on the spot or beforehand. Annie’s friend and next-door neighbor, Amy Dorsey, who works for the NYPD and has seen countless suicide notes, was struck by Annie’s tone—how certain she seemed. “I don’t even want to call it a suicide note,” she says. “It was a good-bye note.”

Just one page long, written in the curly handwriting of a girl half her age, Annie’s note starts as a letter to her son.

My little Michael, my angel—

I loved you more then [sic] life and will love you forever. I tried to give you everything and always be there. I’m so sorry I let you down. I’ll be your guardian angel and that’s a promise. Be strong my special son, I love you.

There’s a word about Paul and Paul’s parents, some reassurance, then more apologies.

Daddy and Me-ma/Be-ba will always be there. You’ll grow up to be strong and caring. Always smile. I loved you the day you were born. I’m sorry I let you down.

The rest is an impulsive assemblage of shout-outs and acknowledgments. Alex and Alexa, I love you so much. Thank you for the smiles and for never giving up. Next, a quick rueful word to her half-sister: Tori—wish you loved us. Me [sic] certainly loved you. I always missed you. She tells Amy and Chris she loves them, drawing a heart in place of the word love. She asks for someone to find a home for her two dogs and her cat.

And then, in the middle, not given any special placement at all, a request:

Mommy and Daddy, please find me.