Free on the right, free on the left, free everywhere.

—Bernard Moitessier, The Long Way, his 1971 account of circumnavigating the globe in a sailboat alone

For two years, three months, and 26 days, while the world economy crashed, and Barack Obama ran for and won the U.S. presidency, and Sarah Palin debuted, and Spitzer resigned, and Sully landed, and Jon and Kate split, and Haiti crumbled, and Avatar opened, and Apple unveiled the iPad to the waiting world, Reid Stowe floated alone.

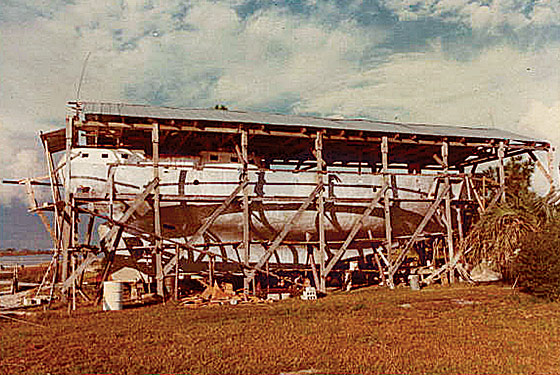

He didn’t know what was happening elsewhere. He didn’t care to know. He wasn’t lost or stranded. He was alone at sea by choice, piloting a 70-foot schooner, the Anne, which he’d built himself, undertaking a mission he’d been dreaming of and planning for most of his adult life: to sail on the ocean nonstop for 1,000 days.

He had a routine. At night, he’d wake every hour or so to check the horizon for ships. He’d sleep until nine in the morning, then get up and put his coffee and oatmeal on to boil. He’d check the GPS and mark his location on the map with an X. He’d update his log, recording his position and conditions. Then he’d retire to a small wooden desk below deck and eat his breakfast and write. Thoughts. Impressions. Dreams. He’d spend the rest of the morning attending to an unending list of repairs: hand-stitching his wind-shredded sails, or jury-rigging a bent bowsprit, or fiddling with a broken electric winch.

At noon, he’d make lunch, drawing from a hold full of six tons of imperishable food—rice and pasta and lentils and peanut butter and Parmesan cheese—maybe adding a handful of fresh sprouts or some salted fish he’d caught and dried on the deck. He’d check his laptop, which received e-mail through a satellite-phone connection, his one tether to the land-bound world. He’d answer his messages, then send back a daily report to be posted on a website, 1000Days.net, being maintained by friends onshore.

“There are a myriad of life support systems to keep me alive and each one needs tending,” he wrote on Day 361. On Day 461: “The food is holding out great. I eat well. The electrical and mechanical systems need maintenance. Pulleys, shackles, turnbuckles and fittings are wearing down like I have never seen before. I had to push so hard to get this mission going that I have been through the aches, the anguish, the barriers, the doubts and fears and they go on. I go on too, it’s worth it.” On Day 842: “You are getting the unedited, live story from me as it happens, right off the cuff, wet off the wavetops and I don’t look back.”

Then he’d close the laptop and get back to the repairs. At 4 p.m., he’d take a coffee break. He’d meditate. He’d paint until dark, his favorite part of the day. At dusk, he’d venture out to the deck and watch the sunset blossom, like red ink dropped in clear water, over the endless horizon of the sea.

He stuck to this routine, perfected in every detail, for the next two years.

He went months without seeing another boat, let alone another human being. In the evening he practiced yoga on a small wooden platform in the salty air. He’d stand on deck and shout, “I love you!” as loud as he could at the waves as they crashed against the hull. He carried a shaman’s mask, a dragon’s head, with him on the voyage, and some nights he’d strip off his clothes, put the mask on, go outside, and dance naked, alone under the vast stars that seemed to belong only to him.

Now it’s August, nearly two months after Reid’s return to the city, and he’s on the phone with Sears. He’s trying to track down a new gas stove for the boat. He’s talking to an automated voice-prompt recording.

“Yes,” he says. “Yes. Large appliances. Large. Appliances.” He finally gets a person on the line. He’s put on hold. He waits. The person returns to tell him that the stove he’s looking for is only available to order online. “Okay, good. Can I order it with a credit card?” he asks. Yes, he can—which is great news, since his partner, Soanya Ahmad, has a credit card. Reid, who’s 58, has never had a credit card in his life.

He hangs up and says, without sarcasm or a trace of impatience, “Well, she seemed real nice.”

Day One: On April 21, 2007, Reid Stowe, then 55 years old, career mariner, adventurer, deep in debt and near dead broke, set sail from a pier outside Hoboken, on a mission to break the record for the longest continuous voyage at sea. He called this trip the “Mars Ocean Odyssey” because, at 1,000 days, it would last roughly as long as a round-trip mission to Mars. Reid had undertaken this kind of adventure before. When he was 19, he went to Hawaii to surf and wound up joining a bohemian sailor on a trip through the South Pacific. Later he built a 27-foot catamaran, christened it Tantra, and sailed it with another man across the Atlantic to Portugal. Then he sailed it alone to Morocco. Then he decided he needed to build a bigger boat.

Reid finished the Anne in 1978, and in 1987, he took her on a six-month voyage to Antarctica with a crew of seven artists, only one of whom had ever been to sea before. When he wasn’t sailing, he was living on the boat, at anchor somewhere, usually for free. He wears hand-me-down clothes from his 16-year-old nephew, and his last apartment was a loft in Soho, in 1988. He’s never lived anywhere as an adult that’s had a refrigerator.

When he set sail that day from Hoboken, he was not alone. He had one other crew member, Soanya, a 23-year-old City College graduate from Queens. She’d never sailed beyond the mouth of the Hudson River.

They’d been friends for four years and, not long after she’d decided to accompany him on his voyage, they became a couple. She lasted at sea for nearly a year, breaking the record for the longest nonstop sea voyage by a woman. But she was suffering from crippling seasickness, and she decided she couldn’t continue. So Reid e-mailed an Australian yacht club and arranged to be met by a friendly vessel. Reid would then venture on, by himself, still two years from his 1,000-day goal.

Day 307: “I sat in the cockpit alone as they powered back towards the land and caught my breath. I reset my sails and turned back to the south. The Mars Ocean Odyssey continues …”

Day 457: “I just found out that Soanya gave birth to our baby boy!”

Soanya had not been seasick; she’d been pregnant. She’d had her suspicions on the boat, but kept them to herself initially. When the news was confirmed, she e-mailed Reid daily with updates and, soon, with photos of their newborn son. She named him Darshen, after the Sanskrit word for “vision.” Reid wasn’t troubled to miss the birth of his son; Reid’s father, an Air Force officer, left for Korea shortly after Reid was born. Besides, it had taken Reid roughly twenty years, with many delayed departures, fractured friendships, and recalibrated dreams, to raise the money and gather the sponsorships to make his trip possible. So there was never a question that he would sail on, no matter what, right to the end.

Day 1,152: On June 17, 2010, under an oceanically blue New York sky, Reid, looking gaunt but exultant, steered the Anne, her sails now patched and yellowed to the color of tobacco stains, up the Hudson, with a barge full of international press trailing behind. The previous record for the longest nonstop sea voyage in history was, depending on how you count it, either 658 days, set by Australian Jon Sanders in 1988 during a triple circumnavigation of the globe (Sanders, incidentally, was the one who picked up Soanya from the Anne), or 1,067 days, which is a rough guess as to how long the Norwegian explorer Fridtjof Nansen spent with his ship stuck in ice as he attempted a trip to the North Pole in 1893. By either count, Reid had broken the record. He’d completed not only the longest sea voyage in history but the longest continuous voyage of any kind ever undertaken by a human being.

A crowd of 300 cheered him as Reid slowly docked at Pier 81 in Manhattan. An organizer urged a small herd of press photographers to step back, saying, “Come on—he hasn’t seen more than six people in three years.” As the photographers elbowed for position, shutters snapping, Reid waved from the deck and shouted, “I see a lot of people here that I love!” then started to cry.

Soanya stood nearby. She’s a petite woman, maybe five feet tall, and she was nearly lost in the crush of the crowd. She waited patiently with the near-2-year-old Darshen asleep in her arms.

And then, for the first time in three years and 56 days, Reid Stowe set foot on land.

“Is that my little baby?” he said of Darshen, still sleeping. He kissed Soanya, then turned to the press. “I wrote some stuff down,” he said. He cleared his throat and read his speech. “This is a new human experience. No one really understands what I did—physically, mentally, spiritually. This was all accomplished through the power of love.” Reporters called out for a statement from Soanya, who said, “We have a really bright and amazing future ahead of us.” Darshen, meanwhile, had woken up and been whisked off by a friend, away from the turbulent scrum.

“What’s next? Where are you going to stay?” asked a reporter.

“I’m going to stay on the boat. I love the boat,” Reid said.

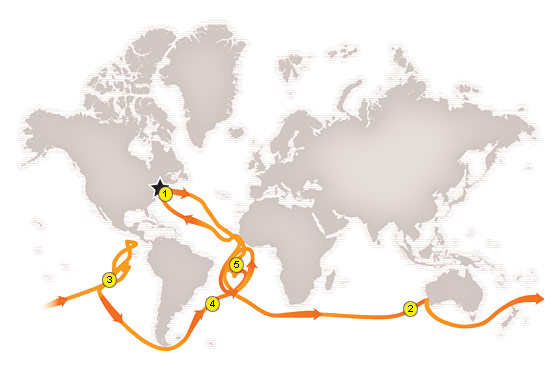

2. Day 307: Soanya departs the Anne, picked up by a yacht off Australia.

3. Day 530: Reid is alerted to the fact that his ship inadvertently traced the shape of a whale.

4. Day 659: A rogue wave overturns the Anne; Reid is briefly knocked unconscious.

5. Day 749: Reid completes his deliberate tracing of the “Oceanic Heart,” as recorded by the GPS.Photo: Map by Remie Geoffroi

You do not ask a tame seagull why it needs to disappear from time to time toward the open sea. It goes, that’s all, and it is as simple as a ray of sunshine, as normal as the blue of the sky.

—Moitessier, The Long Way

The ‘Anne’ bobs lightly in the green water of the Hudson off Hoboken. “You’re looking at the boat that completed the longest sea voyage in history!” Reid often shouts to visitors who wander by, to which one visitor responded drily, “It looks it.”

“I know, and I wouldn’t change a thing!” Reid answered brightly.

The Anne’s not seaworthy at the moment. Ropes need replacing, masts need repairing, and winches have seized with salt and rust. Reid has months of repairs ahead of him, but he’s not discouraged. “Sometimes I look around New York and think I may be the only person in the city living in a home I built with my own hands,” he says proudly. Soanya and Darshen, who’d been staying with her family, are also now living on the Anne. Darshen is a bubbly and curious toddler, and he finds the schooner to be a fascinating playground. He rambles fearlessly over wooden steps and ledges, exploring the enticing corners and nooks, his legs dotted with red bites where mosquitoes snuck through the netting under which they all sleep. On hot days, of which there were plenty this summer, Darshen plays under a blue plastic tarp that Reid’s strung over the cockpit, splashing in a large, translucent plastic bin half-full of water, which serves as a makeshift kiddie pool.

Reid’s driver’s license expired while he was at sea, so when he needs to run errands, he rides his bike to the nearby path station to go to the dentist, or the bank, or to photocopy the hundreds of pages of journals he kept, a job that takes two hours and leaves him so antsy, standing next to that rattling machine, that he starts doing yoga squats in the copy shop.

One day, the family needed to get off the boat for a few hours, while one of Reid’s friends worked on sanding and revarnishing the deck. When they returned, Soanya was worried about all the fiberglass dust. “Fiberglass dust is toxic!” she said.

Darshen lunged toward his wading pool, reaching to splash in the water.

“Darshen, don’t put that water in your mouth!” she called out.

“There’s no dust in there. Do you see any dust in there?” Reid said.

“I don’t need to see it! If it got in, it got in.”

“Do you want me to pour it out?”

“Yes, I think you should.”

And over the water went into the river.

Reid is gradually adjusting to being a father. Darshen is gradually warming up to Reid. Reid has a full-grown daughter, Viva, from a previous relationship, who also had a baby while Reid was away, his first grandchild; his daughter and granddaughter greeted him on the pier when he returned. Previously, though, Reid’s life was sailing and everything else was secondary. The only thing you could count on was that, one day, he’d sail away again. Now he’s ready to be a family man. One of his recent chores was to cut and hang a perimeter of black netting all around the deck, to make sure that Darshen wouldn’t wander away and accidentally fall overboard.

While Reid was at sea, and Soanya was raising Darshen alone, the two of them would talk by satellite phone, their voices seeming scratchy and faraway. Sometimes she would put Darshen on. But Darshen had only an abstract idea of where his father was, or even what “father” meant at all. If someone showed him a picture of a sailboat in a book, he’d point to it and say “Daddy.”

During his thousand days at sea, Reid survived one collision (Day 15: with a freighter, which grazed the Anne) and one really bad storm (Day 659: a monster wave upended the Anne and knocked Reid unconscious in the galley; he suspected the boat had rolled completely over because, when he came to, rice was stuck to the ceiling). But the worst day, he thinks now, was the day when Soanya decided she had to quit.

After she left, Reid started to despair that the voyage was hopeless. The Anne was damaged. The work was endless. The sails were shredding. He’d sew them by hand and they’d shred again. Eventually Reid pulled down all but one of his sails. He stopped setting courses and let the wind take him where it might. The pain in his arms from the constant work got so bad it started to wake him up at night. He prayed for God to send Jesus and the Buddha to heal him. Then he had a vision: Jesus came and laid his hand on Reid’s left arm and the Buddha appeared and laid hands on his right arm. And God appeared to Reid and he was 60 years old with a long white beard, just like in old Italian paintings. At one point, the vision changed and Reid saw floating there in front of him an enormous platter of barbecued spare ribs. But he refocused and the ribs vanished and Jesus and Buddha reappeared and the ship lurched and God and Jesus and Buddha all bumped heads. Then the Buddha turned to Reid and winked at him.

One day, as Reid drifted, a friend e-mailed him with a curious message: “Reid, look at your chart. You’ve drawn a whale.”

Reid checked the chart—it was true. His ship had inadvertently traced the rough outline of a whale in the sea.

He took this as a sign. This was the spirit of the sea, speaking to him. From that moment on, he knew he would make it. He could go two more, five more, ten more years if he needed to.

When astronauts are on space voyages, they sometimes experience a phenomenon called “the overview effect”: an overwhelming, euphoric sense of connection to the universe. Sailors on long voyages have reported similar experiences. The mystic, transcendent possibilities of solitude have long attracted shamans and holy men, and the lure of solo sea travel has transfixed adventurers throughout history.

Now Reid had sailed alone for longer than them all.

Back on land, Reid’s progress was being monitored closely by three distinct groups. There was Reid’s loyal band of supporters, who maintained 1000Days.net. There was Soanya and their new baby. And there was a third group, whose interest was entirely malevolent: a group of commenters posting on a website called Sailing Anarchy.

The website caters to racers, the kind of hard-core weekend sailors who compete in regattas and fetishize sleek, expensive modern craft. On the site, they’d scoffed at Reid’s mission, posting on a message board that eventually reached nearly 30,000 comments. At the beginning, one commenter wrote, “100 days would be a stretch.” Later, one wrote, “He dead yet?” They ridiculed his voyage as not sailing but floating, a kind of “nautical pole-sitting.”

One commenter, who called himself Regatta Dog, became particularly, disturbingly obsessed. He dug up old court papers and posted them online, including a report that Reid once owed over $11,000 in child support to Viva’s mother, as well as Reid’s federal conviction for pot smuggling in 1993, for which Reid spent nine months in jail. Regatta Dog even tried to find out Soanya’s return flight to JFK and meet her at the airport for an ambush interview on video. But he got the wrong info, so he simply walked around the terminal asking other befuddled passengers about the lunacy of a 1,000-day sailing voyage, then posted that clip on YouTube.

These commenters consistently portrayed Soanya as a flaky acolyte or a hypnotized groupie, but she is neither. She’s a strong-willed, well-spoken, thoughtful young woman, who was taken with the idea of living free of the consumer obsessions and expectations of the modern world. She met Reid back in 2003, when he was living on the boat, docked off Manhattan, and she was a photography student at City College, drawn to the waterfront as a romantic escape from the cold geometric canyons of the city. Reid was out working on the boat. She said hello and asked if she could take some pictures. He said sure, then asked, Why don’t you come aboard?

She returned to the waterfront a week later to give him prints of the photos, and Reid had a boatload of people ready to sail for the day. He invited her along. She spent most of the ride chatting with other passengers, while Reid, the busy captain, at home in his element, piloted the boat and entertained his guests. He didn’t pay much attention to her. Later, he sat down, put his arm around her, and said, “So—do you have a boyfriend?”

People were always coming and going, artists and sailors, and Soanya became a semi-regular member of Reid’s informal crew. She liked to listen to him talk about meditation and yoga and sustainable living, or his theories on spirituality and connecting to the universe. These were all things she also thought about, but she had never found anyone among her young friends who could talk about them with any authority, if they even cared at all. She was still in school and working as an office intern, and she came to hate the idea that this might be the whole of her life. Dressing up in office clothes, hewing to a schedule, spending every day penned in a cubicle.

Eventually Reid told her about his dream to sail uninterrupted for 1,000 days, because eventually he told everyone about this dream. It had become a running joke among his friends. Oh, has he invited you yet to sail for 1,000 days? But she considered it. And one clear day, while the two of them sat on the boat on the Hudson, Reid was expounding on the voyage and Soanya blurted out, “I’ll go.”

Early on in their voyage, the two of them both posted lists on the 1000Days website titled, “Ten quick reasons why I like it here.” Reid’s included: “I like being with Soanya on a grand adventure. I like being king of an insecure kingdom. I feel like something good could happen.”

Her list was slightly different. It included: “It’s good to be away from commercialism, noise and stress. I found the wonderful partner to show me the magic of the sea. I’m not stuck doing something I don’t want to do. No one is telling me how to be.”

How can I tell them…? Tell them and not frighten them, without their thinking I have lost my mind.

—Moitessier, The Long Way

When the English yachtsman Francis Chichester completed the first solo navigation of the globe with only one stop, in 1967, he was knighted by the queen. When Moitessier, a sailor from French Indochina, completed a trip around the globe, in 1969, he was hailed in France as a philosopher-poet of the sea. His boat, the Joshua, is still on display in a French museum. When Reid Stowe returned from his journey, he hoped the mayor might be there to greet him. Actually, he hoped the president might greet him, though he knew that was unlikely. But it didn’t seem entirely inappropriate.

Instead, he did some newspaper and radio interviews and got booked on CBS’ The Early Show (it was later canceled) and found out he’d only be allowed to moor his boat for one night in Manhattan. So he scrambled to find a friend with a space in Hoboken. Reid is still optimistic, still full of love for the world, but he’s also confused and slightly frustrated that, for example, not a single sailor has come to visit him to ask how he completed this record-setting voyage. It’s almost as if no one understands what he’s accomplished. When he first returned, he’d been surrounded by reporters asking questions like, “What did you miss most—a hot shower or ice cream?” And Reid, fresh from three years alone communing with the ocean and having nightly revelations on the nature of love, thought, When you’re in the presence of an illuminating gift from the heavens, you don’t think, Gee, I miss ice cream. I didn’t miss a thing out there.

Moitessier would understand. Moitessier, a great inspiration to Reid as a young man, was competing in a race around the world called the Golden Globe in 1968, and he was well in the lead when he decided to change course and simply keep sailing. He explained this in a note, which he flung by slingshot onto the deck of a passing ship, that read in part: “I am continuing non-stop because I am happy at sea, and perhaps because I want to save my soul.” He later wrote that, looking back on his decision, he only regretted the inclusion in the note of the word “perhaps.”

“We’re going to have a good life now,” Reid says on the boat. “We don’t know what it’s going to be. We may not have much money, but we’ll be people who know we did something good for humanity, and everyone will know it, too. And we’ll be respected for that, and loved for that, and my son will grow up coming into that. What’s worth more than that?”

The three of them plan to live on the boat through the winter. They have a wood-burning stove, and there’s still plenty of food in the hold, another year’s worth at least, by Reid’s estimate. And at the end of that year, who knows? Reid is planning another voyage, maybe a slow tour of the sacred sites of the Atlantic Ocean, or a voyage down the East Coast that Reid wants to call “Keeping the Spirit of Adventure Alive in America.”

He’s also hooked up with a literary agent, who’s paired him with a successful co-author, so that’s good. The writer has several Times best sellers on his résumé, and co-wrote autobiographies of William Shatner and Johnnie Cochran. Reid also hopes to mount an art show in Manhattan of the 100 or so paintings he completed on his voyage. One day, he unpacked these paintings to show them to his friend, a curly-blonde French-Canadian art collector named Anne-Brigitte Sirois. Most incorporate collages of sea maps and cosmic swirls and photos of Reid at the wheel of the Anne. One of the collages includes a photo of him and Soanya embracing. When he shows that painting, Darshen wanders over, runs his hand over the photo, and says, “Mommy and Daddy.”

Later, Soanya sits alone on the deck and thinks about the ocean. Her parents were not happy when she announced she was leaving on a boat for three years with a man more than twice her age, but they took her in when she returned, a year later, pregnant, and helped her raise her son. As for life on the ocean, she both misses it and doesn’t. She’s not a sailor, she’s decided, not like Reid. She remembers how he would sit out happily on the deck and do yoga with the salt-wind licking at his face, and she’d retreat down below to do her yoga on the bed. Reid gets tremendous pleasure from pulling ropes and setting sails, but to her it’s just work; she doesn’t enjoy it at all. The one part of sea life she does miss, though, is how simple and direct it all was. Out there, you relied on yourself and no one else. If you were hungry, you’d fish. If rain was falling, and you were thirsty, you’d go out and catch the rain.

She’s done most of the parenting because, as she sees it, she has a two-year head start on Reid. He’s a patient father, sometimes too patient, letting Darshen toddle off toward unseen perils. But he’s getting better. And she’s started to see Reid in some of Darshen’s expressions. She’s noticed they’ve got the same mouth. And Darshen has really taken to the water. He welcomes visitors cheerily to the boat by name if he knows them, and if he doesn’t, he greets them by shouting, “Hi, person!”

On one recent afternoon the three of them sat together on the yoga platform, cross-legged under a bright and placid sky. Reid and Soanya closed their eyes and chanted Om. Unexpectedly, Darshen, sitting at their feet, joined in. They sat like that, eyes closed, chanting in unison, for a long, edifying moment.

Reid opened his eyes and shouted out joyfully—Hey!—and gave Darshen a big hug, and Darshen laughed. And Soanya thought, When you’re all together like that, it really doesn’t get any better. For that moment, the three of them, alone yet together, may as well have been a million miles from the rest of the world.

Day 23:

Soanya growing sprouts.

All photographs courtesy of Reid Stowe

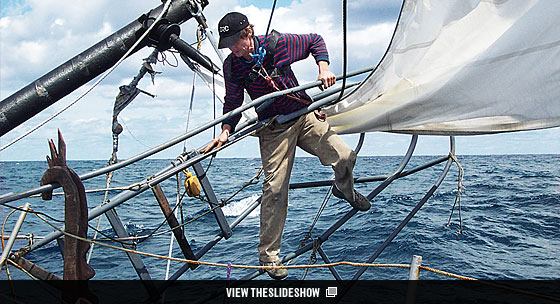

Day 15:

Repairing a bent bowsprit after a collision with a freighter.

All photographs courtesy of Reid Stowe

Day 640:

Facing down a fierce Cape Horn gale.

All photographs courtesy of Reid Stowe

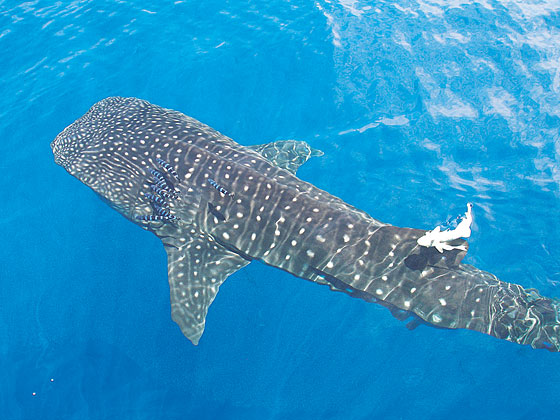

Day 876:

A whale-shark sighting.

All photographs courtesy of Reid Stowe