I t’s closing in on midnight on a drizzly Monday, and Jay Bakker, son of Jim and Tammy Faye, is having a spiritual moment of sorts on a pleather banquette in the back recess of the Williamsburg bar Union Pool. On the concert stage in front of him, his best friend, the Reverend Vince Anderson, fronts a band called the Love Choir. The woman playing sax wears dark sunglasses under the stage lights, the trombonist looks like a trippy Jesus, and the music has a funky soul sound that Jay refers to as “dirty gospel.” Already, Anderson has shed his black suit jacket, and sweat drips from his bangs onto the keyboard that’s programmed to sound like a church organ. He begins the set with a Tom Waits–style incantation, growled out over the packed house:

I am an atheist.

I am a Jew.

I am a Muslim.

I am a Christian.

I am whatever you have a problem with … tonight.

Tonight’s message—that religion is divisive, a bane rather than a balm—is one that Bakker, the fallen scion of American’s most infamous Christian family, knows his way around. But Bakker isn’t thinking about himself right now. He’s thinking about the country seething over the “ground-zero mosque,” about the umpteenth round of Middle East peace talks, about the soldiers who are finally returning from a war in Iraq that’s been considered an American crusade. He’s thinking about just how much RELIGION DESTROYS, as a tattoo close to his armpit reads, and how seriously, seriously fucked up that is. He’s thinking, too, about Revolution, the church–cum–religious movement he helms, part of which is unfolding right now, whether or not the Williamsburg waifs who’ve packed themselves into the dark concert hall realize it.

The Love Choir is the unofficial musical component of Revolution. For those seeking a more explicitly religious experience, sermons are held Sunday afternoons in Pete’s Candy Store, another bar a few blocks away. Most people out tonight have come for the music and the cheap drinks; they haven’t come to find Jesus. But then again, Bakker isn’t out to save any souls or be a beacon of Christian light in the moral morass of New York City. He’s trying to do something of the opposite: to use New York City to save Christianity from itself and its rigid ideas of identity, faith, and worship.

In a manner that borders on proselytizing, Bakker, an Evangelical Christian, has mounted a multifaceted attack on the Christian Establishment. In addition to his Brooklyn ministry, he travels regularly to churches and festivals, appears on television news, and has a large online following (his Twitter feed has over 4,000 followers). Both because of his lineage and his strong language, he has become an unofficial spokesman for a growing group of young, disaffected Evangelicals attempting to splinter from the mainstream church—and call it to task in the process. “Christianity has been on the wrong side of a lot of issues,” Bakker says—and this, he believes, has gone on too long to allow for niceties. “We like to just kind of rip the friggin’ Band-Aid off. We’re about as subtle as a bull in a china shop.”

As if to prove the point, Anderson is now pacing the proscenium, his hands raised over his head in the manner of an old-school revival preacher, howling lyrics about turning water into wine. “I wouldn’t be drinking so much if I didn’t go to church so often,” one guy says, sidling up to the bar as Anderson slides down a banister into the crowd and screams, “Tonight, this is a temple! Hallelujah!”

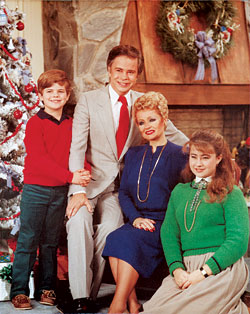

I f anyone should recognize religion as spectacle, it is Jay Bakker, whose birth on December 18, 1975, was announced to America when “It’s a boy!” flashed across the screen of the Christian show The PTL Club (Praise the Lord). His parents first landed on Pat Robertson’s television network in 1966 with a puppet show for children. A decade later, Jim and Tammy Faye had created their own network empire and were fast on their way to becoming the country’s richest Christian ministry. Jim was filming live the moment Tammy Faye went into labor.

Jay grew up as prince of Heritage U.S.A., his father’s Christian resort and theme park. Opened in 1978 in Fort Mill, South Carolina, Heritage was meant as a one-stop shop for Christian indoctrination and rejuvenation, with campgrounds, TV studios, a church, school, shopping complex, and water park. Heritage attracted about 6 million visitors a year and, at one point, was the third-most-popular theme park in the nation (after the two Disneys). Jay and his older sister, Tammy Sue, went to church and school there, and they could go weeks without seeing a person who wasn’t connected to the PTL ministry. “The whole world was based around what my dad did,” Jay says of that time. “I thought my dad ran the world.”

Jim and Tammy Faye certainly weren’t the only ones who benefited from the prosperity gospel they preached; having a theme park fully at his disposal helped Jay win friends. But he was an insecure child, chubby, uncomfortable with being paraded in front of the camera every Sunday. He struggled with undiagnosed dyslexia and developed an ulcer when he was 9. Because his family received hundreds of death threats, he was constantly under the watch of bodyguards, and because his parents were busy running PTL, these handlers effectively raised him.

Then, in 1987, Jay’s world disintegrated. Tammy Faye overdosed on prescription medication. While she was still at the Betty Ford Center, news was released that Jim had had an affair, which led him to cede control of the PTL ministry to Jerry Falwell. Falwell confiscated the Bakkers’ home near Heritage, along with much of its contents, and the family retreated to their house in Palm Springs, where Jay helped his father hang sheets over the windows to deter the camera crews camped outside. “Everything I knew was just completely gone overnight,” he says. “At 11 years old, it was just like, ‘Okay, now I have to start a new life.’ ”

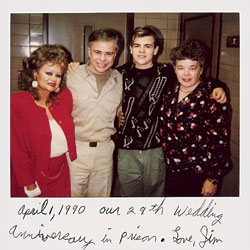

Meanwhile, a grand-jury investigation into PTL was being launched, and Jim was found guilty of 24 counts of fraud for selling more “lifetime memberships” to Heritage than the resort could accommodate. He was sentenced to 45 years in prison. Jay, desperate to help his father, cold-called other famous pastors, begging them to write letters on his father’s behalf (all but Jimmy Swaggart declined). Mostly, he felt helpless. He started drinking when he was 13, and would sometimes use his mother’s eyeliner—the most famous eyeliner in the world—to make himself look goth. He was suspended from school for punching a kid who said his father was being raped in prison. When Tammy Faye decided to divorce Jim, Jay was the one who told him. By the time he dropped out of tenth grade, he was smoking pot and dropping acid, which caused him to have terrifying flashbacks until he was put on the antipsychotic medication Thorazine. He gave up drugs but upped his alcohol intake.

When Jim Bakker left prison, after serving a reduced sentence, in 1994, his son was spending up to $400 a week in bars and frequently blacking out. Jim arranged for him to attend Master’s Commission, a boot camp of sorts in Phoenix for kids considering joining the ministry. Jay dropped out after a week, convinced that his family had been excommunicated and that he was cursed for having the last name Bakker. He had no desire to sign up with mainstream religion again.

But it was at Master’s Commission that he first heard about Revolution, a new ministry being formed that seemed intentionally to be setting itself apart from anything staid. Sermons involved smashing a TV with a sledgehammer. Punk and hard-core bands played before services. The goal was to get past the posturing of religion and to make it relatable to people like Jay—kids who were turned off by the moralizing and cheesy melodrama of the Jim and Tammy Faye generation.

Jay offered to work for the fledgling ministry, helping to jump-start a church that was soon getting recognition for its unorthodox approach. By the time he was 21, he had moved to Atlanta and become minister of his own branch of Revolution. He held services in bars, inviting curious skate punks he met at his job at a record store and posting signs around town that said AS CHRISTIANS, WE’RE SORRY FOR BEING SELF-RIGHTEOUS JUDGMENTAL BASTARDS. It worked. Jay’s flock swelled to about 60 members, and soon he was managing a staff of five.

Revolution was originally just a rebranding of old-school Christian theology: rebellious in affect, but not communicating a message that looked very different from, say, Billy Graham’s. The pose of defiance was enough to draw Jay back into Scripture, but as his personal understanding of the Bible developed, his theology became more progressive and radical. He married at 23, and when his wife got accepted to a graduate program at NYU in 2006, Jay saw it as an opportunity to move his church into liberal terrain. He packed up his Bible Belt apartment and headed for Williamsburg.

C onventional wisdom has it that pastors’ children either rebel or end up pastors themselves. Bakker has managed to do both. “I’ve been called the grunge pastor, the punk-rock pastor, the tattooed pastor, the David Cross of Christians,” he says. “Whatever the next thing is that happens to involve tattoos and clothing, I’ll probably be called that.” But to say he’s a prodigal son is both simplistic and not really true.

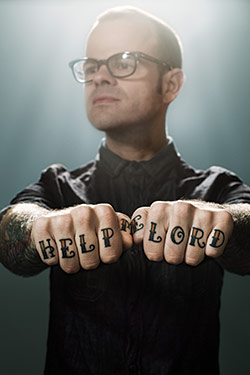

Bakker’s relationship with his mother remained very close until her death from cancer in 2007, after which he had HELP ME LORD tattooed across his knuckles. His bond with his father has been more strained. The two can go for months without talking, and Jim—who has remarried and adopted five children with his new wife—does not always join Jay and Tammy Sue for holidays. But Jay blames any awkwardness between them on difficult expectations rather than on real conflict. “I think my dad’s a pretty sincere guy—when he’s on TV,” Jay commented in One Punk Under God, a documentary series made about him in 2006. “He just kind of needs an audience.” Jim has preached at Revolution in New York; Jay has been a guest on his father’s current show, which broadcasts from Branson, Missouri. And just as his relationship with his parents never really ruptured, neither has his belief in God. Even in his angry teenage years, Jay simply assumed that God hated him.

“All the stuff I’d been taught my whole life didn’t seem to be adding up to what’s in the Bible.”

Bakker’s real rebellion has been against mainstream Christianity, which he doesn’t think has much to say about forgiveness. He was 20 when he entered AA (“I’ve never had a legal drink”), and his theology has certainly been shaped by the program: He now says he drank in part to get over his guilt about drinking, a stranglehold that was released once he came to realize that “God loved me no matter what.” This experience led him to resent Christian legalism, the dos and don’ts that are so much a part of modern faith, and this sent him to the Bible. “I started reading the Bible for myself for the first time,” he says, “and I was just blown away by it. All the stuff I’d been taught my whole life didn’t seem to be adding up to what’s in the Bible.”

The problem with Christianity these days, as Bakker sees it, is not that it conflicts with our modern understanding of science—the Richard Dawkins critique—but that it conflicts with our contemporary views of morality. “The younger generation is just like, ‘This seems contradictory to people I love. Why are certain people being ostracized?’ I read about Jesus, and then I’m told that we should vote this way, but it seems like Jesus wasn’t for war. It doesn’t even seem Jesus liked war. How does ‘Blessed is the peacemaker’ become ‘Our God, our Jesus wants us to kill people?’ How does ‘Blessed are the poor’ become ‘We shouldn’t put money into tax issues that help them’?”

Bakker is certain that if Christianity actually modeled itself on the life of Christ, then these contradictions would disappear, leaving behind the most basic tenets: Jesus was resurrected, and he died for our sins. “There’s just something about the idea of grace and the life of Christ,” he says, “ that I can’t get away from.” The rest of Protestant Christianity, however, he’s basically prepared to ditch—a stance that pushes him beyond the far liberal wing of the Evangelical Christian community and into what is known as the “Emergent” ministry.

The Emergent movement is not an organized force in American theology; most of its members would probably dispute being members of anything. But it is a way of referring to a growing number of churches and ministers—like the Void collective in Waco, Texas, and the theologian Brian McLaren—who attack the fundamentals of fundamentalism. They tend to be pro-choice and support gay marriage, and they don’t fret over premarital sex. They welcome atheists and embrace doubt. They like to read Nietzsche during services.

And though Bakker is hesitant to use the term himself, Revolution has cohered into one of the nation’s most vibrant Emergent churches. “The reason why traditional Christianity works so well is because it tells people that things happen for a reason,” says Peter Rollins, a pioneer of the Emergent movement. “We don’t want to suffer; we want an easy answer. You can fill stadiums with that. But at a community like Revolution, they don’t have an answer for people who are suffering. They say, ‘We don’t know why this is happening, but we’ll suffer through it with you.’ ” Or, as Bakker puts it, “Faith isn’t answers all the time. Faith is helping you deal with the questions.” His Facebook page lists his religious views as “Changing.”

None of this thinking has endeared Bakker to the conservative-Christian behemoth. “I think a movement founded on rebellion is going to collapse under the weight of its own moralism,” says the Evangelical writer Ted Kluck, who accuses Revolution of substituting the arrogance of the traditional church with its own. To others, Bakker is not moral enough: He is engaging in “cafeteria Christianity,” picking only the parts of the faith that suit him. By focusing on grace, he is absolving sinners. He’s been threatened physically at speaking engagements and been told he’s leading people to hell. But Bakker speaks like a true believer. “Another type of reformation is happening,” he says. “And when a reformation is happening, the reformers aren’t recognized as reformers. They’re seen as heretics.”

My religious reeducation begins in earnest one day this summer when Bakker arrives at my apartment with several dog-eared Bibles in a messenger bag. I, too, grew up God-fearing and south of the Mason-Dixon Line. My great-grandmother rarely missed an episode of The PTL Club and sent in regular donations. I once confessed to the leader of my weekly Bible study that I might be a bit of a doubting Thomas, at which point the good woman explained just what I could expect if I chose to believe that Jesus was not my personal lord and savior: unfathomable cold followed by unfathomable heat, unending pain, an abyss where I would be cut off from my family, and where I might cry out for Jesus to save me, but it would be in vain because I had doubted him for one second one afternoon when I was 12.

I hightailed it out of the South as soon as I could. But in college, while others seemed able to jettison any trappings of religion, I was not. If belief and disbelief are two orbits that never intersect, as has sometimes been suggested, I’ve often felt like a particle bounding untethered between them. In other words, I’m enough of a believer to be wary of Bakker’s message and enough of a doubter to be wary as well.

Over a six-pack of Diet Coke and between a number of cigarettes smoked on the fire escape, we go verse by verse through the tomes, picking through some of the key issues that rankle or rally modern-day Christians: homosexuality, premarital sex, abortion, women’s rights, marriage, divorce, Heaven and hell. Bakker points out the inconsistencies in the text, the varying interpretations, the parts that have been taken out of context; and rather than being alarmed that there’s no biblical imperative, he finds this liberating. “To me, Christianity is not a moral code,” he says at one point. He believes this kind of thinking belongs to a culture rooted in the concept of good works and fed by a capitalist notion of faith by transaction, where success as a Christian is tallying souls saved and donations made. “It’s like fine print. It’s like, ‘Here’s the Good News!’—and they get you in and comfortable, and then they’re like, ‘Okay, here’s the actual reality: Jesus loves you just the way you are, but not actually.’ ”

In 2005, shortly before moving to New York, Bakker publicly came out as a gay-affirming minister. It’s a stance he believes to be biblically substantiated, and as we sit on my sofa, he proves it, going systematically through the “clobber” verses of the Bible that have traditionally been used to deem homosexuality a sin. He argues that the very word homosexual didn’t appear in the Bible until 1958, and that it has been translated from a Greek word that could be referring to the sexual practices of pagan idol worship. In a reading that could outliteral the literalists, he views “sodomites” as simply people from Sodom. “And Sodom,” Bakker says, “was destroyed for a lack of hospitality.”

But Bakker’s support for homosexuality has had consequences. After he made his conviction public, the wealthy Christian family that was his major source of funding withdrew its support. One by one, his speaking engagements were canceled. He had to lay off his staff. “By this time we had health insurance,” he says. “We had a great board of directors. But we just didn’t have the finances anymore.” In a crushing YouTube video from that era, Bakker begs a sea of stony African-American faces at a southern church to support gay marriage, or at least not condemn his support of it. “It’s hard for me,” he says from the pulpit, “when people who’ve been through such persecution and been judged against, all of a sudden, they don’t want freedom for anybody else.” The congregation, which had been lively moments before stares at him, silent and hostile.

Compared with his charmed upbringing in the PTL kingdom, Bakker’s life is now fairly monastic. His wife left him in 2007. He has held on to their railroad apartment in Williamsburg, sharing it with a cat named Pedro. He is still paying off credit-card charges from the move, and though he receives a salary from Revolution, it isn’t always able to pay him in full. He no longer has health insurance, and he sometimes gets behind on rent.

Close to 10,000 people download Revolution’s sermons each week, but asking for donations is not high on the church’s list of priorities—a tricky proposition, anyway, when your last name is Bakker. “We’d rather have you here than your money,” he frequently says. Looking back to the riches his father knew at PTL but “from the viewpoint of being a minister now whose church is barely making it,” Bakker says he understands why “people find hypocrisy in a preacher having more than one house.” More than anything, he recognizes how isolating money and power can be. “I remember one time I said, ‘Dad, why are preachers so freakin’ crazy?’ And he’s like, ‘Because you just get in your own world.’ I would love to invite someone like Joel Osteen to come live with me for a month, grow a beard, and just go by Joe. Let him be among people who aren’t church people, who aren’t in that whole bubble, and experience what it’s just like to be normal.”

Bakker recently finished reviewing galleys of his second book, Fall to Grace, which will be released in January. Though it will have a “bit of a refresher course at the beginning for anyone under 30” who may not remember the Bakkers, the book is not a memoir (as was his first book, Son of a Preacher Man). It is, instead, an attempt to synthesize the grace theology he’s been developing for over a decade. Its message is rooted in the Book of Galatians, in which the apostle Paul chastises several churches he founded for becoming too legalistic, for trusting laws rather than Christ’s free gift of salvation, and for using those laws to exclude the people who don’t follow them.

O n a recent Sunday afternoon, Revolution decides to try something new.

“We’re having Revolution Question and Response,” Vince Anderson announces as he and Bakker settle into bar stools on the stage of Pete’s Candy Store. “Um, notice the use of language. We do not have the answers. I repeat: We do not have the answers.”

The congregation titters, and Bakker smiles back at them a little sheepishly. Under the stage lights, he looks astoundingly like his father. His large eyes swim behind thick glasses. There’s something about him that seems a little gun-shy. He still has a slight Carolina twang. When he’s nervous, he tells jokes that aren’t always funny.

It’s hard not to respect someone who won’t abandon the church even as it tries to abandon him, and who aggressively searches for truth without claiming that he owns it. Still, while Bakker and Anderson have the sympathy and attention of their audience, I can sense parishioners trying to work out what they think of Revolution. Once you strip so much out of Christianity, what is left? How do you agree with a church that is still figuring out its message?

But as I’m sitting there, close to the back and beer in hand, it occurs to me that maybe the opposite of faith isn’t doubt. Maybe the opposite of faith is certainty, a comforting belief in your own rightness. To a greater degree than most Evangelicals may care to admit, Jay Bakker’s open-armed ministry is an extension of what his parents created. Jim and Tammy Faye were much more tolerant than other televangelists; in 1986, Tammy Faye famously interviewed a gay minister who had been diagnosed with AIDS. But theirs was a theology of aspiration—believing is easy, and believing leads to success—and it didn’t encourage its followers to doubt their faith or themselves. This, it seems to me, is what Jay is offering: a Christianity that allows for, and is even sustained by, failure.

Among the questions asked—but not answered—at the sermon that day: What happens to the souls of unborn babies? Is God calling us to give up meat? Should Christians live in communes? What’s a good church in L.A.? Does hell really exist?

That last one gets everyone’s attention. Bakker points out that the Bible itself can’t quite decide what “hell” is: a waiting room? A lake of fire? A dump outside of Jerusalem?—and that it depends on your interpretation of the Book of Revelation. After talking for a while, though, he admits that whatever the Good Book might say, he just has trouble with the concept of fire and brimstone. “I have a hard time because everything I know about Jesus and grace and love and forgiving your enemies—hell would sound like God doesn’t practice what he preaches. I want to question hell.”

Bakker grins ruefully and suggests that maybe they should move the discussion out to the bar. “We’re already in enough trouble for what we’ve said today.”

“Would you like to pray?” Anderson asks. And yes, Jay Bakker would.