One afternoon last June, the quaint silhouette of a three-masted sailboat made its way into New York Harbor and pulled up at the Red Hook Marine Terminal. The Black Seal, a 70-foot-long schooner, had just completed a 3,000-mile wind-powered round trip to the Dominican Republic. There, it had taken on twenty metric tons of cocoa beans, mostly from La Red de Guaconejo organic-cacao cooperative, whose beans are said to yield chocolate with notes of “sweet pipe tobacco” and “Cabernet Sauvignon.”

The 400 bags of beans were headed for the Williamsburg factory of Mast Brothers Chocolate, maker of artisanal chocolate bars wrapped in gorgeous, thick paper printed with repeating anchors, Florentine swirls, antique bicycles. At first, the brothers bought off-the-rack wrapping paper at a nearby art-supply store, but they now design the patterns in-house and have the paper printed in Long Island City, and the almost-opulent packaging has been no small part of their success.

The boat itself was equally artisanal: It had been built by hand, over 25 years, in the Cape Cod yard of its captain, a man the Masts have called “an American hero.” One of the brothers, Rick, had stayed home from the trip with his pregnant wife, late in her third trimester, but Michael had been aboard the ship for the whole four-week journey from Cape Cod to the Caribbean and back. A lot of work goes into supplying Whole Foods with $9 single-origin craft-chocolate bars sprinkled with Maine sea salt, “created using solar salt houses” on “the mystic coast of Maine.”

The brothers both have magnificent Civil War–period beards. They grew up in Iowa and moved to New York to become a chef and a filmmaker, only to be waylaid by artisan dreams. When they speak of their chocolate, they’ll say things like it “represents more than just a candy bar; it represents a new way of crafting food,” and it embodies “a fiercely independent, almost Emersonian spirit.” In their shiny new 3,000-square-foot showcase factory on North 3rd Street, they feed their direct-trade cocoa beans into a custom-built winnower before milling the nibs in repurposed stone grinders. (They replaced an earlier blown-glass version of the winnower, fearing glass might end up in the chocolate.) There’s an upright piano in one corner for impromptu ivory-tinkling.

Touring the space recently, elder brother Rick, who runs operations, takes pains to point out that Mast Brothers is a bean-to-bar chocolate-maker—sourcing the cocoa, roasting it—rather than a mere chocolatier that outsources production. But if the Masts are Luddite chocolate-makers, they’re also figures in a very contemporary caricature. More than anyone else in the New Brooklyn artisan movement, they exemplify to an almost implausible degree the daguerreotype stereotype of the bristly hipster, in newsboy cap and tweed britches, pedaling his penny-farthing to a north Brooklyn industrial space to make handcrafted nano-batch sweetmeats. If you’ve ever wondered what a Christopher Guest documentary about Brooklyn artisans might look like, Google “Mast Brothers YouTube.”

Michael, younger, laconic, handsome, heads sales but leaves it to his big brother to declaim the company’s unimpeachable artisanality. As Rick explains, they avoid preservatives like soy lecithin, develop customized “roasting profiles” to bring out the unique character of each type of bean, and let their chocolate “rest” for a luxurious 30 days (makers of high-end dark chocolate believe this improves flavor). Their chocolate is used by chefs like Dan Barber and Thomas Keller and Alain Ducasse, but they do their own local distribution in the company station wagon.

“The restaurant and food industries have some of the gnarliest environments,” Rick says. “We’re trying to reinvent that for the modern world.” It’s a rather grand vision of chocolate modernity. In a back office, an employee sits at a computer editing a movie about the schooner trip. In another room, a man is hand-sprinkling that Maine sea salt onto still-soft chocolate bars. The wind-powered Caribbean sourcing voyage, arranged by the brothers as a kind of anti-industrial act, a proof that old ways could be made new again, was merely their latest, most exuberant step back in time.

The schooner is obviously great PR, not that the brothers Mast would ever put it that way. “We don’t have a marketing department,” Rick says. “We have an education department.” For a chocolate bar that has sailed into the hearts of urban sophisticates largely under power of its packaging, backstory, and media-bait olde-tymey-ness, this statement sounds like rank corporatespeak, but the brothers seem to earnestly regard their candy bars as a pedagogical tool. And the White Man’s Burden top notes aren’t limited to their org chart. They have the used burlap cocoa sacks sewn into tote bags, which they sell. There are 25 employees, most of them full time and each with medical and dental insurance. Capital and labor eat lunch together at a common table.

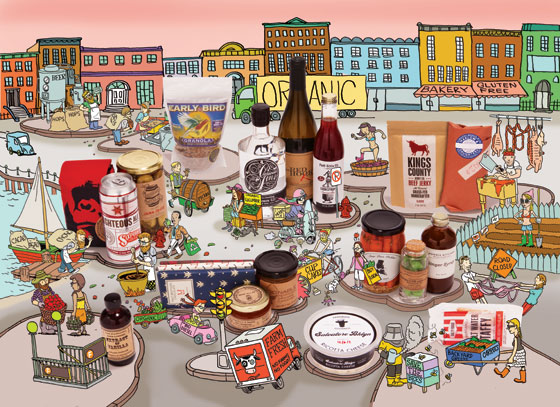

Brewers, Bakers, & Beef-Jerky Makers

A few members of the tribe.

Listening to Rick talk, it’s easy to be seduced by the vision: a world, or at least a borough, where thousands of salvaged-teak schooners ply the oceans, or at least the Gowanus Canal, bearing Mason jars full of marmalade made from windfall kumquats. It’s like a child’s dream. The supermarket aisles are lit by Edison bulbs, staffed by scruffy men in butcher’s aprons, and stocked with cruelty-free dog food and hand-pulped toilet paper. But wait: Should the TP come from new-growth forests (more environmentally correct) or old-growth (more authentic)? Those lightbulbs are beautiful, but aren’t they inefficient? If small batch goes global, how will the idiosyncrat perform this pageant of superior taste? (By embracing Wal-Mart-scale production as a “retro” counterculture?) And is there really a mass market for $9 chutney? In other words, can twee scale? And if it can, and we do find ourselves hurtling toward this nightmarish Brooklandia, is it still okay to like those serrano pepper and “vanilla & smoke” chocolate bars?

By Brooklyn is a small shop that opened last April on Smith Street in Carroll Gardens with the mission of selling only products made in Kings County. Among the store’s inventory, made by some 120 different vendors, are $29 “reclaimed slate” cheese boards from the Red Hook–based Brooklyn Slate Company and wee $58 terrariums from a Dumbo company called Undiscovered Worlds.

The store itself is a kind of walk-through diorama, a snow-globe fantasy of New Brooklyn in miniature—the boroughwide artisan arms race stuffed into a storefront. There’s packaging featuring vaguely Victorian typefaces, and scents and flavors that seem simultaneously retro and contemporary: P&H Soda Co.’s lovage soda syrup, Liddabit Sweets’ beer-and-pretzel caramels, Salty Road’s bergamot saltwater taffy. There is Clinton Hill–based Early Bird granola (“gathered in Brooklyn”); Park Slope–based Brooklyn Hard Candy (“handcrafted in Brooklyn”); Gowanus-based Brooklyn Brine Co. pickles (“proudly hand-packed in Brooklyn”); and Greenpoint-based Anarchy in a Jar jam (“made with love in Brooklyn”). As much as these are variations on a theme, they’re also a theater of marketing one-upmanship. “Small-batch” Jam Stand jam from Red Hook is displayed near “very small batch” Bittermens bitters from Dumbo and that Early Bird granola, which is baked in “tiny batches.” Clearly, small is the new big. This is packaging that, as much as telling you what you’re buying, is telling you who you are—a Brooklynite of a sort scarcely imaginable ten years ago. A Breuckelenite, let’s say.

This is not the Brooklyn on your map but a notional place consisting mainly of the western “creative crescent” that arcs from Greenpoint south to Gowanus and runs on freelance design work and single-origin, crop-to-cup pour-over coffee. It’s the Brooklyn where bodegas stock Fentimans “botanically brewed” Dandelion & Burdock soda and where the Dumbo headquarters of crafting juggernaut Etsy has air ducts literally, no joke, swaddled in crocheted cozies. It’s not the Brooklyn of Brownsville, East Flatbush, Ocean Park, Canarsie. By Brooklyn owner Gaia DiLoreto, a 37-year-old former IT worker, is black and wants to be “a role model to young black women,” she tells me. She had one intern from East New York who “knew nothing about artisanal food. An $8 candy bar was insane to her.”

Fortunately for DiLoreto, there’s a robust audience for whom that candy bar is the very apex of civilization. Area code 718 romantics love to see their hometown’s name every time they pull something out of the fridge, to pretend a borough of 2.5 million people is a small English village, to partake of a Shop Class As Soulcraft authenticity that’s missing in their Twitter-addled, cubicle-drone lives, and to reassure themselves that Brooklyn is more “real” than Manhattan and not just an annex with shorter buildings. Sightseers from 212 are equally avid buyers: salving their one percent class angst, signaling their membership in the elite tribe of ethical aesthetes, shoring up their idea of Brooklyn as that exotic but taxi-accessible place where all the kooky artists and kids live and create stuff for the adults in Manhattan who actually make the world go around. And then there are the tourists who compose half of DiLoreto’s business. “Everyone loves Brooklyn,” she says. “That’s the place everyone wants to be, to have a part of, to be a part of. I want to do everything I can to leverage that.”

You don’t hear words like leverage coming out of many of the artisans’ mouths, and at a time when we’re learning about the “pink slime” used as filler in public-school hamburgers, you can’t resist applauding the impulse to reject the industrial status quo—to make fresher, healthier, better-tasting food, to take entrepreneurial risks and seek meaning in one’s work. But it’s equally hard to avoid the sense that the new Brooklyn economy is moss growth in the shade of larger corporate forces. Plutocrats of a certain stripe like their baubles to come with meaningful, brow-furrowing backstories, and the artisans, with their small-scale production and deliberate inefficiencies and expensive ingredients, need the postindustrial wealthy to buy their $14 pickles and $10 granola. The buyer of $9 jam, after all, isn’t another maker of $9 jam. It’s the guy whose multinational robotic assembly line spits out jars of $1 jam. Or it’s his trustafarian son, the Global Jam Logistics heir. Or it’s the private-equity guy who just offshored GJL to a sweatshop in Bangalore.

I recently ate a bowl of Early Bird’s Farmhand’s Choice granola with milk for breakfast. The bag cost me $9, but with its judicious sweet-savory use of olive oil, salt, and pecans, it was distractingly tasty. A couple of weeks later, I buy a bag of Early Bird’s Jubilee Recipe (cherries and pistachios) and a bag of its Choc-A-Doodle-Doo (chocolate and coconut). They are even better. I buy a second bag of Jubilee. Then a second bag of Choc-A-Doodle-Doo. I’m in deep now.

I cherish the little pouches atop my refrigerator, with their rustic-urban design of a colorful bird, stalk of wheat in its beak, flying over a cityscape. Because the granola is “gathered in Brooklyn,” I can take pride in supporting local manufacturing (local mixing, anyway). The organic rolled oats and organic pumpkin seeds and organic coconut and organic brown sugar pleasingly affirm my endorsement of sustainable farming practices. The use of whole ingredients, slow roasting, and “tiny batches” testifies to my discerning appreciation of the artisan and to my rejection of the industrial food system. The dried sour cherries and salt and extra-virgin olive oil prove the sophistication of my palate: I am beyond the easy pleasures of butter and unadulterated sweetness. I don’t do yoga, but if I did, I am reassured to read on the pouch that a recommended occasion for enjoying the granola is when I’m “striking warrior pose.” And by buying this granola, a sticker informs me, I am “giving to GLSEN, an anti-bullying organization.” I know $9 is a lot to pay, but this isn’t just food.

At the same time, taken together, the artisan products, and particularly their packaging, can give you the willies. With all that label cross talk—We’re more Brooklyn than thou! More handcrafted! More “consciously” sourced!—we get more than we barter for. You only think you’re just buying a jar of artisan pickles. Suddenly, by association, you’re one of those people packing a ukulele into your $130 Fjällräven rucksack, swinging by Bierkraft to pick up a growler of Flying Dog Raging Bitch Belgian IPA, and riding the G to Greenpoint to take part in a late-night hootenanny in a former stapler factory. But what if you’re not one of those people? Or actually, what if you are one of those people, and one of the things that makes you one of those people is your acute allergy to feeling like one of any kind of people? Maybe you believe bullying is bad, and appreciate the virtues of yoga, and are a moderately environmentally responsible citizen, but you also feel uncomfortable having something in your shopping cart that is ostentatiously palimpsested with as many political slogans as a seventies guitar case. And as great as those pickles may taste, maybe you find it kind of objectively embarrassing, and possibly inexcusable, to spend $14 on them. Maybe. But that granola is pretty fucking awesome.

There is the twee comedy of eating Brooklynishly, and then there’s the twee sincerity of producing Brooklynishly: wide-eyed entrepreneurs slogging through the nitty-gritty of business-building. The word artisan, shopworn as it may be, is usually not, actually, an affectation.

One product By Brooklyn used to carry was Maiden Preserves jam. It came in a beautiful jar. Alison Roman and Eva Scofield were co-workers at the Williamsburg outpost of Momofuku Milk Bar, the David Chang dessertery. Roman was a sous-chef; Scofield’s job title was “Etc.” Both were itching to do something on their own, and when Milk Bar got its own table at the Brooklyn Flea, Kings County’s favorite artisanal trading post, in early 2011, chef Christina Tosi said that any employees with their own project could sell through the Milk Bar table. “I said, ‘Let’s make jam,’ ” Roman remembers. “ ‘Wouldn’t it be cool?’ ” Tosi let them use the Milk Bar kitchen during off-hours, and each of the women kicked in a couple of hundred dollars for ingredients and materials. “We came up with a name and got everything together fast,” Roman says. “We were flying by the seat of our pants.”

They were going to make jam differently. They would use fresh organic fruit and make all the jam themselves. They would offer unusual flavors: vanilla-lemon, grapefruit-hibiscus. Most of all, Roman had her heart set on using one particular jar, a sublime amalgam of glass, rubber, and steel made by a German company called Weck. They were expensive—$1.85 wholesale per jar, compared with others costing about 60 cents each—but Roman and Scofield figured the jars would differentiate their product. “They’re very well-made, adorable, and crazy expensive,” Roman says.

Everything seemed to go well at first. The jam was delicious. The packaging was lovely. The women retailed their jam for $7, until people told them they should charge more and they raised the price to $9. “ ‘Handmade in Brooklyn with local fruit’—that’s all you had to say for some people,” Scofield says. “They’d say, ‘We’ll take eight.’ ” Williamsburg retailer Bedford Cheese Shop picked them up. The Vanderbilt, a fashionable bar and restaurant in Prospect Heights, started using their jam in a cocktail after Scofield, coming in for her shift as a waitress, gave a jar to the bartender. West Elm wanted to carry them. Gilt Groupe asked for samples. The women were navigating a well-trod artisan path from hobbyist daydream to entrepreneurial venture, seeming to slalom effortlessly between Brooklyn’s small-is-good ideology and the growth imperative.

But there was a disconnect. The jam sold well at the Brooklyn Flea, but even there, they rarely did more than break even. There were unanticipated expenses—liability insurance, incorporation, various licenses and certifications, logistical snafus. After Milk Bar gave up its Flea table, Roman and Scofield had to rent their own, and after both women stopped working there, they had to rent commercial kitchen space. “People would say, ‘You guys are doing so well,’ ” Roman says. “I’d say, ‘No, we’re not.’ There’s this fantasy, but it’s not as simple as putting fruit in a jar and selling it.”

There was also an emerging divide between the partners. Roman wanted to handwrite each label and cook every batch in an eight-quart kettle pot and stick with selling to baby and bridal showers and cute boutiques. Scofield wanted to spin off a line with cheaper jars, maybe a private label, and sell to bigger markets. Roman’s new job, in a magazine test kitchen, left her with less time to cook. “It was becoming clear we didn’t have the same vision,” Roman says. Finally, in December, Roman and Scofield stopped making jam. Now they hardly talk.

Scofield, meanwhile, is moving ahead with her own new jam business. This time, she’s working up a business plan and is considering using a co-packer to make the product. Above all: “I’m sourcing different jars.”

While the carefully considered choice of what jar to put your homemade jam in might seem like design-junkie hairsplitting, economic-development types hope that a borough’s worth of would-be jelly moguls could actually add up to something more. And they’re not totally crazy. Only a few years ago, the idea of a resurgence of any kind of manufacturing in Brooklyn seemed like nothing more than a nostalgic daydream, right up there with the comeback of egg creams and soda fountains. In 1978, there were 116,000 manufacturing jobs in Brooklyn. By 2000, there were just 43,000. By 2009, another 53 percent of the jobs were gone, leaving only 20,000. But all that vacated factory space—at least that part not converted to residential lofts—beckoned. People calling themselves locavores started to care about where their food came from and how it was made. The DIY movement took hold. And with the recessionary job-market crunch, suddenly the opportunity cost of launching your own business shrank dramatically. So many Brooklynites started cooking up batches of jam, chocolate, pickles, and granola that artisan aspirants had to specialize. Now you can buy Q artisanal tonic water and Empire artisanal mayonnaise and DP Chutney Collective artisanal pear mostarda. And oh, that nostalgic daydream of egg creams and soda fountains returning to Brooklyn? On a recent Thursday afternoon, Eastern District in Greenpoint was serving up chocolate egg creams using local artisanal P&H soda syrup made with Mast Brothers cocoa husks.

Few people in California in 1849 made money panning for gold; the smart play was to sell picks and shovels. Likewise, in Brooklyn’s artisan boom, the biggest upside isn’t necessarily in pickles or beard oil (yes, that’s a thing). Take the not-at-all-small-batch Pfizer Building, on Flushing Avenue. Viagra and Lipitor were both made here, in the 600,000-square-foot building on the site of the pharmaceutical giant’s original headquarters. The building’s new developer thinks it’s perfectly suited for conversion to food manufacturing, and a number of artisans have already moved in, including Kombucha Brooklyn, McClure’s Pickles, Brooklyn Soda Works, Steve’s Ice Cream, and People’s Pops. A bin labeled “mustache covers,” intended as an anti-contamination measure in the Pfizer era, feels like a wink to the building’s newest tenants.

And Pfizer is only one node in the ecosystem. Every weekend, up to 6,000 people visit the Brooklyn Flea, navigating their Bugaboos past the likes of Kings County Jerky and Writing Machines, a pair of women specializing in “typewriter curation.” Andrew Tarlow’s Williamsburg-based Marlow food mini-empire also sells cheese boards made from fallen trees and leather footballs sewn from the hides of the grass-fed cows that were ground up to make your hamburger at his restaurant Diner. And the artisans themselves are participants in one giant kibbutz-y swap meet: Sixpoint Brewery used Mast Brothers cocoa nibs in its Dubbel Trubbel ale, Steve’s Ice Cream uses Kombucha Brooklyn kombucha in its Red Ginger Kombucha sorbet, Liddabit Sweets uses Salvatore Bklyn ricotta in its fig-ricotta caramels, and the list of collaborations goes on and on.

You might get the idea, from all this, that the artisans’ day-to-day lives are a charmed blur of tasteful design and enchanting aromas and Zooey Deschanel. Which makes the contrast all the greater when you behold the unglamorous reality of a lone guy in a hoodie holding a blow-dryer, heat-sealing bottles, one at a time, in an unheated, windowless storeroom in Greenpoint—as P&H Soda’s Anton Nocito was doing on a recent sleety morning. Or of tattooed, 31-year-old Shamus Jones, pacing amid stacks of boxes because there’s nowhere to sit in the raw garage space in an unmarked carriage house in Gowanus that is pickle company Brooklyn Brine Co.’s headquarters.

A second job is the norm—DiLoreto, the By Brooklyn owner, estimates that only a quarter of her vendors are full-time artisans—but waiting tables to pay the rent is almost an anachronism. The old waiter-actor has been eclipsed by the actor-artisan. Now the risky dream job is starting your own pickle company, and the art hustle is your fallback. Bob McClure, whose McClure’s Pickles brought in over a million dollars last year, had a role in a Visa commercial as recently as this past December.

And every remotely ambitious artisan sooner or later finds himself making trade-offs of one sort or another. Early on, Jones had to accept that as a New York pickle-maker he would need to compromise his locavore mission when he discovered that in this region cucumbers grow only three months of the year. “Friends said, ‘Dude, you make pickles. You can’t not produce for three-quarters of the year.’ It was a hard thing to wrestle with in my mind.”

Rob Behnke and Matt Burns have never been hung up on purist definitions of Brooklynness. Burns grew up in South Dakota and got a job when he was 14 at a taquería in Sioux Falls. There, he made the fried chips and fresh salsa and fell in love with the condiment. Behnke, who has an M.B.A., grew up in New Jersey. In 2007, through Craigslist, they became loft mates in Bushwick, where they were both part of the Todd P underground-music scene. One night in April 2008, Burns made some salsa for a show Behnke had booked in the Opera House basement, and the feedback was good. The next morning Behnke said, “Hey, we could start the cool salsa company.”

Right out of the gate, the Brooklyn Salsa Company had five flavors, one for each borough. Their packaging used bold colors and sleek typography; their only preservative was lime juice. Within three months of their 2010 launch, they were in Fairway and fifteen Whole Foods supermarkets in the region. A month after that, they were picked up by Fresh Direct. By December 2011, they had 500 accounts, and they expect to have over 1,000 by the end of this year. Co-packers upstate and in Kentucky make their salsa, and they’re selling 10,000 to 15,000 jars every month. They are moving away from identifying their flavors with New York City—keeping Brooklyn, but switching the other four flavors to San Francisco, Mumbai, Havana, and Mexico City. They want to be “a national brand by year two,” Behnke says, “and the first international salsa company.”

That kind of good old-fashioned entrepreneurship can cost you friends in the east–of–the–East River artisan scene. The Brooklyn Kitchen, one of Brooklyn Salsa’s first retail accounts, stopped carrying the product. “I liked it better when it was a fresh product, not jarred,” co-owner Harry Rosenblum says. “They expanded. I saw it in a lot of places. It was a less special thing to offer.” DiLoreto, the By Brooklyn owner, refuses to sell Brooklyn Salsa and has also nixed McClure’s Pickles (run out of Bed-Stuy but made in Michigan) and Kombucha Brooklyn, which boasts on its label “Born in Bkln” but is made upstate.

Sitting in his work space in the Pfizer Building, surrounded by live experimental cultures for new flavors and a prototype for a home kombucha kit he’s making for Williams-Sonoma, company founder Eric Childs, 26, takes issue with people he calls “localists. That’s an extremist mentality I don’t agree with,” he says. Bedford Cheese Shop’s Charlotte Kamin agrees. “I’m curious how sustainable it all is. Brooklyn has thought of itself as unique for a long time. I’ve never been focused on local. It’s what the tourists ask for. I’m seeing a lot of producers stop. The reality is you don’t make money or you overextend yourself.” Childs’s take-it-out-of-the-city story is a case in point. “I wouldn’t have been able to grow,” he says. “The rent here is four times what it is upstate. Utility and labor costs are different. But my family’s in Brooklyn. All the money comes back here. I used the name Brooklyn not just because of the appeal but because I love Brooklyn.”

Steven Eisenstadt loves Brooklyn, too. Cumberland Packing, the company his great-grandfather founded, has made the iconic pink Sweet’N Low saccharine packets since 1957 and is still going strong over by the Navy Yard.

Walking through an invisible haze of particulate, an FDA-compliant hair cap in place, you can literally taste the company’s history. Sweet’N Low is just one of the products that Cumberland packs, and the flavor in your mouth keeps changing as you pass from room to room: Sugar in the Raw, Stevia in the Raw, Agave in the Raw, Nu Salt (sodium free), Butter Buds (natural butter flavor), NatraTaste Blue (aspartame), NatraTaste Gold (sucralose). The Brooklyn factory produces around 55 million packets a day. Last year, revenues approached $200 million, up from $150 million in 2005. This is what a small Brooklyn startup looks like after 65 years of growth. By all business logic, the company shouldn’t be here.

Partly it has stayed because of inertia, Eisenstadt, the current CEO, says, and partly for sentimental reasons. “My grandfather taught me to play chess here. My dad still comes in every day.” Five employees have been here for more than 40 years, and 200 have been here for more than twenty. Some employees are the third generation in their families to work here, and 200 live within walking or cycling distance. While Cumberland has lost some workers, it has never laid anyone off. It has never had a strike. “Job retention and creation were a big part of our mission all along,” Eisenstadt says. “We could automate and make more money. We could move to New Jersey and make more money.” The rent would be cheaper. The company could avoid the $80 per truck in tolls that it currently pays to bring materials across the Hudson. But the Eisenstadt family has resisted selling. “If private equity came in, the jobs would be gone.”

In other words, what’s keeping Sweet’N Low in Brooklyn isn’t all that different from what motivates many of the anti-industrial young artisans. But it’s hard to pin a borough’s economic hopes on sentimental attachment, especially since the most successful companies will have the fewest reasons to remain in Brooklyn: The bigger they grow, the greater the economies of relocating for cheaper labor and land. Hard, but not impossible.

Eisenstadt sometimes plays golf with Steve Hindy—a former AP foreign correspondent, now 63, who learned homebrewing from diplomats in Cairo who had perfected the process while stationed in Middle Eastern countries where beer wasn’t available. After he moved back to the U.S., in 1984, he and Tom Potter, a onetime Chemical Bank loan officer, launched Brooklyn Brewery. At first, they had all their beer made by a brewery upstate, but in 1996, the company, which projects sales of $40 million to $45 million this year, built a brewery in Williamsburg. Its capacity is now 60,000 barrels a year, and it will soon grow to 100,000. The brewery has 57 full-time employees in Brooklyn, and a $12 million expansion is under way.

When Hindy told one of the original investors that “we wanted to call the beer Brooklyn, even though he was a lifelong Brooklyner, he said, ‘Are you sure you want to? I’m not sure it will play well in other places.’ At the time, in the early eighties, Brooklyn had a very different image.” Back then, Brooklyn meant shuttered factories and ruined neighborhoods and had yet to be reimagined as a garden of artisanal delights. “But I guess it takes a guy like me, from the Midwest, to believe in Brooklyn, to be taken by Brooklyn. It’s turned out to be a very good name.”

Beverages Grady Laird, Dave Sands, and Kyle Buckley Grady’s Cold Brew Photo: Jonathan Nesteruk

Beverages Anton Nocito, P&H Soda Co. Photo: Jonathan Nesteruk

Beverages Antonio Ramos and Caroline Mak, Brooklyn Soda Works Photo: Jonathan Nesteruk

Beverages Colin Spoelman, Kings County Distillery Photo: Jonathan Nesteruk

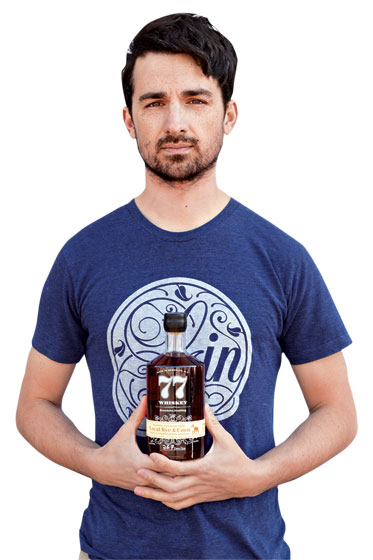

Beverages Brad Estabrooke, Breuckelen Distilling Photo: Jonathan Nesteruk

Beverages Kari Morris, Morris Kitchen Photo: Jonathan Nesteruk

Baked Goods Matt and Allison Robicelli, Robicelli’s Cupcakes Photo: Jonathan Nesteruk

Jams Sabrina Valle and Jessica Quon, The Jam Stand Photo: Jonathan Nesteruk

Jams Laena McCarthy, Anarchy in a Jar Photo: Jonathan Nesteruk

Spreads Elizabeth Valleau and Sam Mason, Empire Mayonnaise Co. Photo: Jonathan Nesteruk

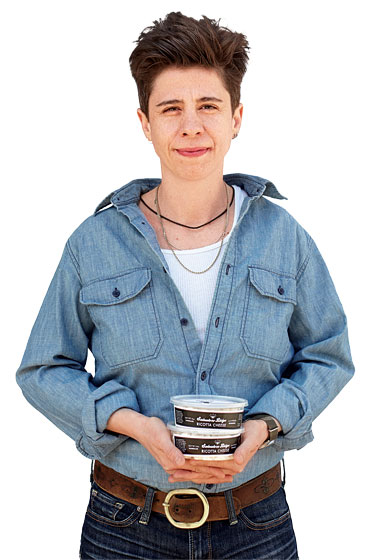

Spreads Betsy Devine, Salvatore Bklyn Photo: Jonathan Nesteruk

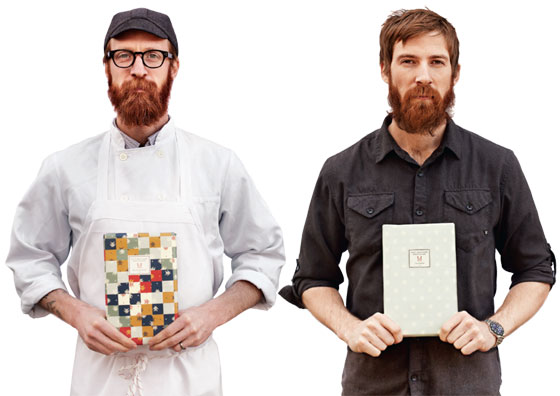

Sweets Rick and Michael Mast, Mast Brothers Chocolate Photo: Jonathan Nesteruk

Sweets Liz Gutman and Jen King, Liddabit Sweets Photo: Jonathan Nesteruk

Sweets Nathalie Jordi, Joel Horowitz, and David Carrell, People’s Pops Photo: Jonathan Nesteruk

Sweets Jenna Park and Mark Sopchak, Whimsy & Spice Photo: Jonathan Nesteruk

Sweets Marisa Wu, Salty Road Photo: Jonathan Nesteruk

Sweets Nekisia Davis, Early Bird Granola Photo: Jonathan Nesteruk

Savory Chris Forbes and Evelyn Evers, Sourpuss Pickles Photo: Jonathan Nesteruk

Savory Shamus Jones, Brooklyn Brine Co. Photo: Jonathan Nesteruk

Savory Robert Stout, Kings County Jerky Co. Photo: Jonathan Nesteruk

Savory Matt Burns and Rob Behnke, The Brooklyn Salsa Company Photo: Jonathan Nesteruk

Home Lindsay Carver and Chris Grodzki, Stanley & Sons Photo: Jonathan Nesteruk

Home Sacha Dunn, Common Good Photo: Jonathan Nesteruk