“Don’t be sad,” says Finklestein on his deathbed. “I’ve had 80 good years.”

“But you’re 98!” says his wife.

“I know.”

Except for the occasional doctor’s appointment or bad cold, Irving Kahn hasn’t skipped a day of work in more years than he can remember. And he can remember plenty of them: He’s 105.

That record is vexing to his youngest son, Thomas Graham Kahn, who though 69 and president of Kahn Brothers, their brokerage and money-management firm, is still called Tommy. (Irving is chairman.) How can he take a vacation if his father won’t?

Instead, Tommy threatens to dock his dad for his short workday, which begins around ten and ends by three and often includes a nice bowl of soup. “It’s not like we have so many employees we can afford to have him shluf off,” Tommy says.

Tommy runs the business, which has about $700 million under management. But even though Irving, with his very short stature and very large glasses, looks a bit like a horned owl peering up from his desk—a desk that features both a computer and grip bars—he is no figurehead. His is still the corner office, 22 floors above Madison Avenue. (During the blackout of 2003, he walked down.) He gives or withholds the papal blessing on investment policy and reviews every transaction undertaken by the firm’s youngsters on behalf of clients.

The world’s oldest stockbroker, he first went to work on Wall Street in 1928. “This was before the Depression,” he says, then specifies which depression, as if I might confuse it with the one in the 1890s. Both are real to him; through a chain of memory leading back to his grandparents, Eastern European Jews who settled on the Lower East Side shortly before that earlier upheaval, he can almost touch the Civil War.

More directly, he can touch the technological revolutions that followed. He describes his father’s good fortune in getting into the lighting-fixture business in the years after “Mr. Edison opened his downtown office”—the one that brought electric power to Manhattan in 1882. He remembers with perfect clarity building a crystal radio in his bedroom around 1920 and amazing his mother, who thought music came only from Victrolas, with the music he “caught for free.”

When you’re 53, as I am, and believe yourself to be on the wrong side of life’s unknowable midpoint, a conversation with someone who will soon be twice your age, and who furthermore has retained all his marbles, can be disorienting. For one thing, it has the effect of collapsing a century into a pancake. Czar Nicholas II and Barack Obama, gaslight and computer glow, grandmothers and grandchildren: All are contemporaries, all in sharp focus.

The indiscriminate urgency of memory is disorienting for Irving as well. “I’d rather not know who I was and who I knew and what I did,” he says. “It uses up space I need for today.”

By “today,” incredibly, he also means the future. All conversations with Irving eventually wobble back to his favorite ruts, such as how new technology might affect the viability of companies he follows. “I don’t worry about dying,” he says, assuming it will happen in his sleep. Instead he worries about staying mentally agile, which is why he reads three newspapers daily and watches all the C-Spans. “I know people collect postage stamps, but that’s just one thing. It’s about having multiple interests.”

He does not say multiple attachments; his own upbringing—his mother ran a shirtwaist business out of the home—suggested the value of independence and keeping an eye on the horizon. Newness served his family well: “A new country, a new language, a new public school, a new college.” At his home a mile up Madison—until he was 102 he took the bus—he has, he says proudly, “thousands of books, not one fiction. Mostly I’m interested in what’s on the edges: solar energy, sending vehicles beyond the moon.”

His belief in a personal future that will repay this curiosity—a future I can hardly imagine for myself without worries of illness and decrepitude—is what’s most disorienting about Irving Kahn. You’d think that as he got older, then even older, and then bizarrely old, he’d have had ever more opportunities to despair. And, true, his eyesight and “earsight” aren’t what they were. He can’t walk much on his own anymore. He despises these limitations but ignores or finds ways to outwit them. Loss as well. His wife’s death, in 1996, was a huge blow, Tommy reports, but Irving “put his foot down a little more on the pedal, if that was possible.” When macular degeneration recently made reading difficult, he learned to enlarge the font on what he calls his Gimble.

It helps that he is wealthy enough to have full-time attendants. Also, perhaps, that he has always been a “low liver,” without flamboyant tastes, as his brown, pointy-collared shirt and brown patterned tie attest. He goes to bed at eight, gets up at seven, takes vitamins because his attendants tell him to. (He drew the line at Lipitor, though, when a doctor suggested it a few years back.) He wastes few gestures; as we speak, his hands remain elegantly folded on his desk.

Still, a man who at 105—he’ll be 106 on December 19—has never had a life-threatening disease, who takes no cholesterol or blood-pressure medications and can give himself a clean shave each morning (not to mention a “serious sponge bath with vigorous rubbing all around”), invites certain questions. Is there something about his habits that predisposed a long and healthy life? (He smoked for years.) Is there something about his attitude? (He thinks maybe.) Is there something about his genes? (He thinks not.) And here he cuts me off. He’s not interested in his longevity.

But scientists are. A boom in centenarians is just around the demographic bend; the National Institute on Aging predicts that their number will grow from the 37,000 counted in 1990 to as many as 4.2 million by 2050. Pharmaceutical companies and the National Institutes of Health are throwing money into longevity research. Major medical centers have built programs to satisfy the demand for data and, eventually, drugs. Irving himself agreed to have his blood taken and answer questions for the granddaddy of these studies, the Longevity Genes Project at Albert Einstein College of Medicine in the Bronx, which seeks to determine whether people who live healthily into their tenth or eleventh decade have something in common—and if so, whether it can be made available to everyone else.

What have the researchers learned? Not what Irving wanted to know, which was only whether those who live longer have higher earning power. For the rest, like how he got involved in the Einstein study, he says, “You’ll have to ask my sister.”

His older sister.

“Oy,” says Sophie.

“Oy vey,” says Esther.

“Oy veyizmir,” says Sadie.

“I thought we weren’t going to talk about our children,” says Mildred.

Between 1901 and 1910, Saul and Mamie Kahn—the electric-fixture salesman and his clever wife—had four children: two girls (Helen and Leonore), then two boys (Irving and Peter). By 2001, when Helen turned 100, they were thought to be the oldest quartet of siblings in the world. Helen’s sassy tongue and taste for Budweiser made her a minor celebrity on old-age websites; four years later, upon turning 100 himself, Irving rang the bell at the New York Stock Exchange.

But the family’s DNA may be even more celebrated. All four have participated in Einstein’s longevity research, begun by Dr. Nir Barzilai in 1998. For these studies, Barzilai has assembled a cohort of some 540 people over the age of 95 who, like the Kahns, reached that milestone having never experienced the so-called big four: cardiovascular disease, cancer, diabetes, and cognitive decline. He theorized that these “SuperAgers,” as he calls them, must have something that protects them from all four conditions. Otherwise, when they didn’t have a heart attack, say, at 78, they’d have succumbed quickly to the next thing on their body’s inscrutable list. So instead of looking, as most genetic studies do, for pieces of DNA that correlate with the likelihood of getting diseases, Barzilai looked for the opposite: genes that correlate with the likelihood of not getting them—and thus with longevity.

The top correlate for longevity is one that requires no blood test to discover: having a SuperAger in your family already. (Though Mamie died at 64, Saul lived to 88, exceptionally long for a man born in 1876.) But the results at the DNA level are nearly as strong. Barzilai has so far identified, or corroborated, at least seven associative markers. The most significant is the Cholesterol Ester Transfer Protein gene, or CETP, which in one unusual form correlates with slower memory decline, lower risk for dementia, and strongly increased protection against heart disease. (Among other things, it increases the amount and size of “good” cholesterol.) Only about 9 percent of control subjects have two copies (one from each parent) of the protective form of CETP, while 24 percent of the centenarians do, including all four Kahn siblings.

Other markers found more frequently among the SuperAgers include a variant of the APOE gene that protects against atherosclerosis and Alzheimer’s, a variant of the FOXO3A gene that protects against tumor formation and leukemia, and a variant of the APOC3 gene that protects against cardiovascular disease and diabetes. (This variant alone has been associated with an average life extension of four years.) Having long telomeres—regions at the ends of chromosomes that shorten as you age—is another kind of marker, acting as an instant-read longevity thermometer. There’s evidence, as well, that small stature among the SuperAgers (Irving is now about five foot two) may reflect the influence of a protective factor seen throughout nature; ponies live longer than horses.

Suggestive though they are, these findings so far lack the real-world application that can turn even the most questionable longevity fads, like Resveratrol, into worldwide sensations. After all, as Tommy Kahn puts it, would you really want to know if you have a predisposition for your penis falling off unless there were “some kind of splint” you could get to repair it? (Tommy, a widower, recently remarried.)

But the Einstein project is fascinating for a major reason beyond its science: Its main test group consists entirely of Ashkenazim—that is, Jews who descend, as more than 80 percent of American Jews do, from communities in the Pale of Settlement of Eastern Europe. In longevity news, the spotlight frequently passes from one group to another: Georgian yogurt eaters, Japanese pensioners, the Pennsylvania Dutch. But 540 Jews in a New York–based study of extreme old age is too delicious. The mind cramps with the possibility of jokes.

Barzilai acknowledges as much, telling me first off that most of the original intakes were done by a Gentile nurse named William Greiner. After Greiner visited the participants in their homes, interviewing them and taking their blood, Barzilai would get calls saying that the young man was very nice, but why didn’t he touch the cake they’d prepared?

Mostly gray at 56, Barzilai, Israeli by birth, is a puffball of excitability: twinkling, gesturing, capable of persuading anyone to do anything. Well, almost anyone. His mother, a Holocaust survivor born in what is now Ukraine, refused to let him test her blood. “For her, the genetic studies had already been done,” Barzilai recalls. “And she didn’t enjoy it the first time.”

He laughs, but the twinning of darkness and lightness in his life’s work is no accident. Longevity is the flip side of mortality, as Jews who survived the twentieth century do not need reminding. When a centenarian says she’s Ashkenazic, he takes her word for it: “Do you think there would be impostors?” And when he goes to synagogues to solicit volunteers, he makes this argument: “Yes, we had a miserable history, okay, let’s get over that, we ended up not in such a bad place. And if we’re able to give back, to find genes associated with longevity, it’s really something we have to do. I’m not choosing Ashkenazim because of only a technical point, but also tikkun olam”—the rabbinic injunction to repair the world.

As it turns out, the miserable history is inseparable from the technical point. Barzilai centered his studies on Ashkenazim not because they live longer or produce more centenarians than other ethnic groups. They don’t. It’s that their unusual development as a homogeneous community makes them easier to study at the level of DNA. Genetic research done by Barzilai’s Einstein colleague Gil Atzmon suggests that Ashkenazim branched off from other Jews around the time of the destruction of the First Temple, 2,500 years ago. They flourished during the Roman Empire but then went through a “severe bottleneck” as they dispersed, reducing a population of several million to just 400 families who left Northern Italy around the year 1000 for Central and eventually Eastern Europe. Though their numbers increased dramatically once there, to some 18 million before the Holocaust, studies suggest that 40 percent of today’s Ashkenazim descend from just four Jewish mothers. How proud those mothers would be to know that the reason their mishpocheh has remained far more genetically alike than a random population—Barzilai says by a factor of at least 30—is that until recently their sons almost never married outside the clan.

That likeness means that small genetic differences—as small as one “letter” of DNA code—are more easily spotted on Ashkenazi genes than on those of, say, Presbyterians. Icelanders are good, too: They are all descendants, Barzilai says, of five Viking men and four Irish women. But they are a tiny population, with proportionately fewer centenarians, and aren’t so easy to find in New York. Ashkenazim are plentiful. And because they are also fairly similar in their educational and economic status, some of the variables that can muddy the picture are already controlled.

Others are controlled more explicitly. An Einstein study published in August asked whether the SuperAgers, over the course of their lives, had better health habits than the general population.

The answer was no; their habits were, if anything, worse. They smoked as much or more than others and were no better about diet or exercise. Tommy Kahn described his father’s lifelong eating habits as “lamb chops one night, steak the next.” Exercise was sporadic and mild. “Healthy living can get you past 80,” says Barzilai, “but not to 100.” Something else is at play. When asked what they themselves thought it might be, the participants offered such explanations as genes, luck, and family history. God, says Barzilai, finished last.

God agrees to grant Hyman a wish, with the condition that whatever he asks for, his brother-in-law will get double.

“Okay,” Hyman says, “I wish I were half-dead.”

There was nothing Jewish in the Kahns’ upbringing: no Yiddish, no synagogue, no shtetl sentimentality. Saul and Mamie left Grand Street for Yorkville as quickly as possible. Helen and Peter eventually changed their last name to Keane for professional reasons—in Helen’s case when she started contributing articles about women’s fashion to Liberty magazine in 1936. The editor said the new name would sound more like a writer’s.

Perhaps, but then she’s had many names. Helen Faith Keane is the one she used professionally—not just at Liberty, but as the host of a daily TV talk show called For Your Informationin 1950, and as an instructor of costume history at NYU from 1947 to 1977. Mrs. Philip Reichert is her married name; her husband was a cardiologist who dabbled in sexology. But mostly she’s been called Happy, a nickname acquired at camp at 16 that remains apt 93 years later.

Happy explains this to me as best she can. Though she is perfectly turned out in peach slacks and a chic bouclé jacket, with her nails neatly done in Bungle Jungle red, she is hampered by speech difficulties, the result of two strokes in 2005. Her thoughts are intact, but I can’t understand her except when she puts a huge effort into producing a few clear words. Mostly she lets her live-in caretaker, Olive Villaluna, interpret, a relief apparently compromised by the rare thing Olive gets wrong. At these moments, Happy will sometimes grab my wrist—we are sitting side-by-side in wooden armchairs in her Park Avenue apartment—and wring it like a washcloth. Other times she makes a gesture that looks like she’s firing a small gun. Olive says it’s a tic of her frustration.

But for the most part, like Irving, Happy does not dwell on difficulty, or even on the past. She’d rather see whatever’s on Broadway or in the museums. “She hated that costume show at the Met,” says Olive, “you know, the guy who committed suicide”—and here Happy makes the gun gesture again. “And just recently, in June, she said, ‘Olive, there’s a new exhibition of Capucci’ ”—the Italian fashion designer—“ ‘in Philadelphia.’ ‘Okay,’ I said, ‘we’ll make arrangements.’ She said, ‘No! Right now!’ So we packed our bags and went the next day.”

Listening intently, Happy demands the show’s catalogue, which is brought by Olive’s husband, Joseph. She points at Capucci’s incredible creations, beaming with pride as others do over pictures of their children. Not having any of her own, she has suggested that Olive and Joseph’s baby, due in February, be named Faith.

I have sat with many old women before; it’s a professional hazard, or privilege, and my nature as well. I’ve heard their stories, patted their shocking, soft skin. I have seen them invite my pity and repel it, too. But Happy doesn’t want any of that from me. She wants me to join her in some new experience right now. Do you like Johnny Mathis? Rodgers and Hart? She points to where her piano used to be, as if inviting me to play, but she’s given it to Cornell University, of which she is, it hardly needs saying, the oldest living graduate.

“Happy, you had to stop playing after your stroke,” Olive reminds her. “Before that you played every day. We got back from Mamma Mia! and you played ‘Money, Money, Money’ from memory!”

Oh, well, Happy shrugs; what’s next?

Since she has indicated that she doesn’t believe, despite her family’s evidence, in a gene-based explanation of her longevity, I ask if “just moving on” is part of the secret everyone assumes SuperAgers must have. Can gumption trump decay even at 109?

“I don’t know anything about it,” Olive says she says. “Many people did the same things as she, but they don’t live to be so old.” Happy shrugs again.

“We went to the doctor yesterday,” Olive continues. “She mostly just goes to say hello.” Like her brothers and most SuperAgers, Happy takes few medications, and only since her stroke. “He asked her, because I mentioned that she had lost weight recently and sometimes could not sleep, ‘Are you depressed?’ And Happy said, ‘Why? Why would I be depressed?’ ”

I wonder if depression should be on Barzilai’s list of big diseases that SuperAgers escape. When her husband died, in 1985, Happy gave away her best china and took off for several years of world travel, barely stopping at home except to repack her bags. When she had her stroke twenty years later, she worked harder than anyone Olive had ever seen to restore her ability to speak and write. At first there was only one word she could form, and it’s how she addressed Olive, by her mother’s name: Mamie.

Recalling this, Olive, who’s 39 and from the Philippines, starts to cry. “I didn’t know, when she asked me to live here eleven years ago, we would fall in love with each other.”

Happy wrings my arm. “In America … we have president … his wife … Mamie.”

She smiles triumphantly, then asks me to join her for lunch at Tao, the loud, expensive Asian restaurant down the street.

Klein brags to Cohen about his new hearing aid: “It’s the best one made— I now understand everything!”

“What kind is it?” Cohen asks.

“3:15.”

Happy exemplifies one of Barzilai’s conclusions: that SuperAgers do not age differently from other people, just later. Much later. Many do eventually get hit by one of the big four, or by other catastrophic problems, but 30 years after the rest of the population. The average age at which American women have a first stroke is 72; Happy’s was at 105.

In the meantime, other ailments can take a greater toll than they normally get the chance to. Chief among these are vision and hearing problems, like the kind Irving and his brother, Peter, both have, and mobility problems associated with arthritis. (Irving considers it a triumph when he only has to wake his attendant once a night to go to the john.) Sometimes these relatively minor irritations can be sufficient to do you in. Their sister Leonore, a lifelong outdoorswoman and gardener who preferred that you call plants by their Latin names, was completely healthy when she tripped on a scatter rug in 2005 at age 101. She died a few weeks later.

But mostly such problems won’t kill you. Already, thanks to stents and pacemakers and bypass surgery, some people who, a generation ago, might have been dead at 75 are muddling through their eighties, albeit half-broken and medicated to the gills. Soon, if the promise of Barzilai’s studies is realized, you may muddle much longer, perhaps even to 122, which was the age at which Jeanne Calment—the longest-lived human who could prove it with a birth certificate—died in 1997.

If so, like the Kahns, your happiness may depend on habits of mind, chief among them flexibility, that you would need to have developed decades, or even a whole lifetime, earlier. And on having a determined family member or top-drawer companion to keep you safe from falls, telemarketers, lapses in hygiene, loneliness.

Will it be worth it? Or will it turn out to be an inversion of the classic joke, surely Ashkenazic, about the bad restaurant: The food is terrible—and such large portions!

I too am Ashkenazic, with longevity on both sides. My father’s father, like Irving Kahn, could not imagine retiring; he went to work on a Friday, shul on a Saturday, and died on a Sunday morning, at 89. (My father, now 85, works full time.) My mother’s mother, Anna, from the same part of “Poland-Russia” as Mamie Kahn, drove well into her nineties and only stopped, under duress, when she grew too short to be seen by cars behind her. People were alarmed by the driverless Chevy Nova wandering down the street; I called it the Flying Landsman.

Toward the end, Anna lost some of her short-term memory, though images of marauding Cossacks remained intact. She also, more generally, lost interest. One day, my mother said to her, “Mom, do you know that your birthday’s coming up?” Anna shrugged. “Do you know how old you’ll be?” Another shrug. “Mom, you’ll be 99!”

“Oy,” Anna said. “I feel like I’m 100.”

She didn’t quite make it and was glad. She had always told us that if she ever got sick, she wanted us to put her in a Hefty bag by the side of the road. My mother, on the other hand, made it clear she wanted to live as long as possible, with whatever artificial help was required. The sad irony is that each got what the other wanted. My grandmother lived far longer than her enjoyment of life could justify, though she was never sick. My mother, at only 71, faced with incurable leukemia after surviving colon cancer, changed her mind and asked me, as her health-care proxy, to authorize the removal of life support when the time came. It came quickly.

So when Barzilai says it’s a “good sign” that I look far younger than 53—arrant flattery—and suggests that I have my DNA checked for his various markers, I say yes but worry that I’ll come to regret it. Do I want to find out if I’m likelier to emulate my grandmother or my mother? And anyway, who got the better deal?

I describe the dilemma to each of the Kahns and ask whose wish, my mother’s or grandmother’s, matches their own. Irving sides with my mother’s, if not her outcome. “If you’re alive, you might yet find the answer to something,” he says. “The puzzle you couldn’t solve before. The capacity to enjoy learning is what matters.” Happy agrees; she can think of nothing that would make her not want to keep living.

Mrs. Radosh says to the rabbi, “My husband keeps shrinking! When we married he was five foot eight, and now he’s five foot four. Can you say a blessing for him?”

“Of course: May he live to be four foot ten.”

Peter Keane, the baby of the family at 101, lives with his wife, Elisabeth, called Beth, in Westport, Connecticut, on a pleasant suburban street filled with mature shrubs and trees, including a huge weeping cherry by the driveway. Peter was pretty much fine until 2007, when the glaucoma and macular degeneration that had been under control for years suddenly turned catastrophically worse. Within months he was blind. Now his eyes often weep of their own accord; Beth, always noticing, subtly tucks a tissue in Peter’s fist to cue him.

Aside from that, and a general weakness that makes his cushioned wheelchair useful, he looks to be in great shape. He has a lot of hair, not even all gray; his voice is clear and expressive. Like most old or even middle-aged people, he can lose track or forget a word he’s looking for; the only odd thing about it is how upset he gets when this happens. He’ll stammer on a syllable, fighting to get it out, or give up with a pained cry of “Shit!” Or he’ll bicker with Beth. “If you’d just let me say it!” he yelps occasionally, to which she always responds, “Yes, dear.”

Beth is 67; they met in 1984, when she was 40 and Peter a very youthful divorcé of 73. “He was charming and delightful and fun to be with, and he remains so,” Beth says; when Peter starts telling the story of his life, in vivid and sometimes bawdy detail, you can see what she means. A cross between Zelig and Douglas Fairbanks, he seems to turn up everywhere in the last century’s book of glamorous pursuits, then disappear and pop up again somewhere else.

It does not make his blindness any less painful that most of these exploits involved a camera. After graduating from Cornell with a degree in ornithology in 1932, he went to work, at $17 a week, for Margaret Bourke-White, developing film and assisting on location. “When she went out on the gargoyles”—for her famous shots of the Chrysler Building—“I went too.” Next he’s in Hollywood, an assistant cameraman on the sets of Gone With the Wind and The Wizard of Oz, shooting Vivien Leigh as she escapes from Atlanta in a buggy and watching Judy Garland lip-synch “Over the Rainbow.” Two tours of the Pacific in the Signal Corps with Frank Capra; work on the development of Technicolor; a stint at Screen Gems; and then the balance of his career, until his retirement at 81, in video technology at HBO: All rush forth with a young man’s gusto.

But when he pauses, the stories gutter. Beth restarts him, subtly, with a prompt. Still, his memories, however merry, are soon revealed to be merely dutiful, dragged out for my benefit. If they are worth the effort, Peter admits, “it’s news to me.”

Inanely, I seek refuge from this sadness by exclaiming over a doe snitching birdseed from a feeder outside the window. But of course Peter can’t see that. The gorgeous weeping cherry is someone else’s joy.

“I can’t do much now, really,” he says equably. “I talk to people I used to know on the phone. They ask me how the weather is, and I don’t know. I tell them I never get out. Is that depressing? Very. No cure for it, though. I said when it happened that if you lose your eyesight, you are 99 percent dead. The other one percent, that’s a matter of habit. Except for other”—he struggles to find the word but makes do with an approximation—“instances, I still feel that way: I’d rather die. The other instances are family, Bethy. That’s enough.”

He does not feel the need to adjust either side of this statement, but simply sits with it. So does Beth, her hands folded.

“It also depends on how you decide to go.”

And here Beth changes the subject to happier things: Peter’s two children from his first marriage, his two grandchildren, the time ten years ago when all four Kahns spent a day on the terrace. Everyone seemed so young then, she says. “I’m not sure I even know what old is now.”

Peter does: “Dumb luck.”

At his checkup, Schwartz asks the doctor, “Do you think I’ll live to 100? I don’t smoke or drink or eat rich food or have sex with loose women.”

“So why do you want to live to 100?”

No matter how feisty the study participants on their good days, no matter how upbeat their videos on the Einstein project’s website, aging is for most people a dirty business, whether it progresses slowly starting at age 70 or rushes in 30 years later. In a way, it might be worse at the extreme; when you’ve had so many more years of health, its collapse, or the fear of it, may be more painful. For the Kahns, an expectation of family exceptionalism surely took hold, despite Leonore’s “early” death: Each sibling’s apparent invincibility supported the others’. Their longevity came to seem a matter of willpower, not fate. “I admire what Dr. Barzilai—is he really a doctor?—is doing,” says Irving. “To a point. Where we part ways is in trying to match up one thing that can be passed along with one result. I don’t think it really works that way.”

To scientists, though, the science is compelling. But if a great deal of longevity is genetic, it still expresses itself in unpredictable ways even among the most closely related—much as Mamie Kahn’s pot roast recipe was passed to her children in slightly variant forms. Peter’s aging has been as different from Irving’s and Happy’s as his picture of his early life is from their cheerful version. (He says that his parents were too busy to pay much attention and that the children were friendly but not close.) When Barzilai tells me several times that “there’s more than one way to get to 100,” he means that SuperAgers don’t typically have all the markers he’s studied; just one may be enough. But the statement could also mean that you can get to 100 in different conditions: depressed or happy, trapped or freed.

In any case, researchers are plotting alternate routes. Currently under way at Merck are Phase III trials of a drug that mimics the action of the CETP variant Barzilai has shown to correlate with cardiovascular and cognitive health in the SuperAgers. The results are expected in 2013. And though Barzilai is not affiliated with that project, he is working on his own longevity drugs through a biotech start-up he established with a colleague. One drug is based on a line of peptides he calls mitochines, which decrease with age in the normal population, but not as much among centenarians. He hopes to synthesize the chemical and “put it back in” where nature has leached it away.

Eventually, he says, the idea is to develop all such markers into longevity drugs and to “achieve a greater health span within our potential maximal life span.” Not that he calls them “longevity drugs” in grant proposals, since aging is not itself a diagnosis for treatment and thus not what the NIH looks for. “Instead, I say our mission is to prevent chronically debilitating diseases of old age”—basically, the big four. “There may be a side effect: It may increase life span. If so, we apologize.”

However worthy that sounds, it’s unclear to me whether the baby-boomers who may be the first beneficiaries of such death-delaying drugs are hardy enough to endure the extra decades of nonlethal afflictions they will face instead. And by baby-boomers I mean me. I have a hard enough time waiting three weeks for the results of my DNA test without worrying myself to death. How would I endure 30 extra years like that?

It looks like I won’t have to. Gil Atzmon tells me, in his gruff, amused, Israeli way, that I don’t have any copies of the protective CETP variant. Also, the lab was able to read only part of my APOE gene, so it’s impossible to say much about my risk for Alzheimer’s.

Even the one bit of good news is bittersweet: One sequence of my FOXO3A assay showed the “longevity genotype,” which suggests some protection against the diseases that killed my mother. (Presumably this “good” sequence came from my father.) But then Atzmon sighs portentously. “I’m sorry to say your telomeres are very short. Remember, this is like a thermometer. It was maybe you were stressed that day they drew your blood. But if you were on vacation, or feeling a little healthier, maybe we get a better result.”

I know: The test is descriptive, not predictive; an association, not proof. Still, I ask how bad it is.

“If I would place it in age,” Atzmon says, taking his time to consider, “I would believe you’re currently 75 to 80 years old.”

Oy. I feel like I’m 100.

What does a Jew hope people will say about him at his funeral?

“Look! He’s moving!”

Happy went to Tao for lunch without me. Over the next few days, she also dined at her other favorite restaurants, Lavo and Rue 57. She seemed intent on an even fuller schedule of activities than usual, as if she were checking off a list. She visited the Cornell Medical Center to meet a newly hired archivist, explored the Village in search of a restaurant where she and her husband once ate (it’s now a Starbucks, so she ordered coffee), had lunch at a friend’s apartment, and spent Sunday afternoon at the Central Park Zoo with Olive and Joseph’s nieces.

The next day, Olive noticed a slight wheeze. Antibiotics were prescribed. By Friday, Happy was noticeably weaker while awake and began making odd gestures in her sleep, as if reaching for something in the air in front of her. Olive believed it was Happy’s late husband. “I know that you are here for Happy,” Olive told him, “but please not now.” Over the next two days, Happy would sleep, wake cheerfully, ask to get dressed, have a bite to eat, then fall asleep again, reaching.

There can come a time when people no longer live for themselves but for those who, in a strange reversal, have come to depend on them. Selfishly, we may want our old loved ones to just keep going, if only as a bulwark against our own mortality. Tommy Kahn’s hope is that Irving “can live for another five, ten years, something like that.” Olive wished Happy would live forever.

But on the afternoon of September 25, six weeks shy of her 110th birthday, Helen “Happy” Faith Kahn Keane Reichert died while napping in her recliner, with her lipstick on and her nails newly done in Bungle Jungle red. Until that moment, she had been, many thought, New York City’s oldest woman: a title that, of necessity, is often transferred, if rarely as gently. No breathing tube, no defibrillator paddles—just oatmeal for breakfast, a soft-boiled egg and jam for lunch, and the reaching in the dark for whatever was coming next.

When Beth Keane told her husband the news, he became silent. “It was a deep silence that lasted a minute or two,” she wrote to me in an e-mail. “Then he turned to me and said, ‘You know, I have been expecting this’ ”—and has not spoken of it since. Irving had pretty much the same reaction. Still, the two brothers met at Peter’s house five days later and sat alone for a long time in the kitchen “within arm’s reach of each other,” Beth reports. Irving faced away from the view, which Peter, of course, couldn’t see.

If they were wondering about the value of living so long when it meant facing the death of everyone they grew up with, you can hardly blame them. Even with the miraculous enhancements sure to come in the next decades, longevity is a mixed blessing. For Jews, who are enjoined by their faith and history and meddling grandmothers to be healthy and live long, and to have children who will do the same, it can become such an obsession as to make the time gained seem unworth the worry. Nothing in Barzilai’s arsenal of misspelled genes will address that.

Still, no one wants to stop trying—and I say this as a grumpy 75- or 80-year-old man. In that regard, the real significance of SuperAgers like the Kahns may be in demonstrating the choices more and more of us will face. Do you give up or keep reaching toward the future? Shortly before dying, while Olive was helping her drink some tea, Happy “suddenly held my stomach with her two hands,” Olive says. “And looking on my tummy, she started saying ‘So cute, very very cute.’ That’s the last time she hold me!”

Olive starts to weep. “My problem is I never thought of her age, I treated her like she can go on and go on and go on. But I know she’s with her loved ones. And she left me knowing I was with mine.”

Olive’s baby, it has since been decided, will be named not Faith but Happy. May she live to be …

Helen, Born 1901

Age 1Photo: Courtesy of the Reichert Family and Olive Villaluna

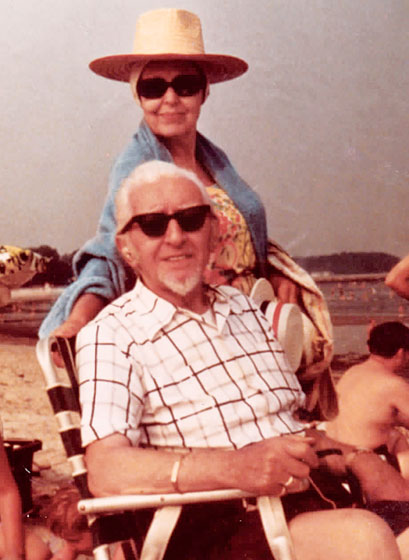

Helen, Born 1901

Age 56Photo: Courtesy of the Reichert Family and Olive Villaluna

Helen, Born 1901

Age 108Photo: Courtesy of Olive Villaluna

Leonore, Born 1903

Age 7Photo: Courtesy of the Kahn Family

Leonore, Born 1903

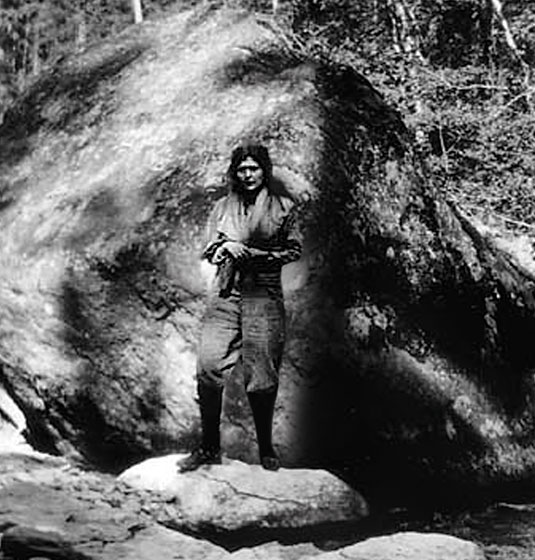

Age 17Photo: Courtesy of the Reichart Family

Leonore, Born 1903

Age 22Photo: Courtesy of the Reichart Family

Leonore, Born 1903

Age 99Photo: Courtesy of Olive Villaluna

Irving, Born 1905

Age 1Photo: Courtesy of the Kahn Family

Irving, Born 1905

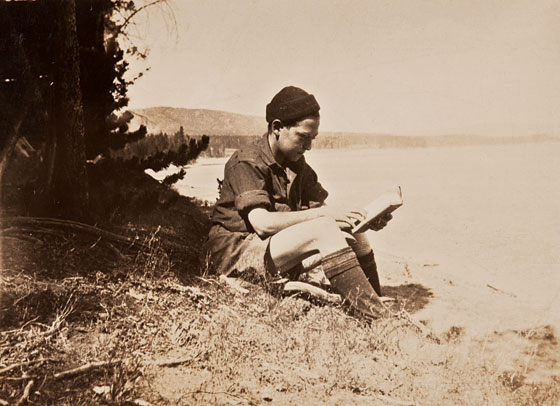

Age 16Photo: Courtesy of the Kahn Family

Irving, Born 1905

Age 45Photo: Courtesy of the Kahn Family

Irving, Born 1905

Age 105Photo: Christopher Lane for New York Magazine

Peter, Born 1910

Age 1Photo: Courtesy of the Kahn Family

Peter, Born 1910

Age 35Photo: Courtesy of the Kahn Family

Peter, Born 1910

Age 50Photo: Courtesy of Peter Keane

Peter, Born 1910

Age 100Photo: Courtesy of Peter Keane