|

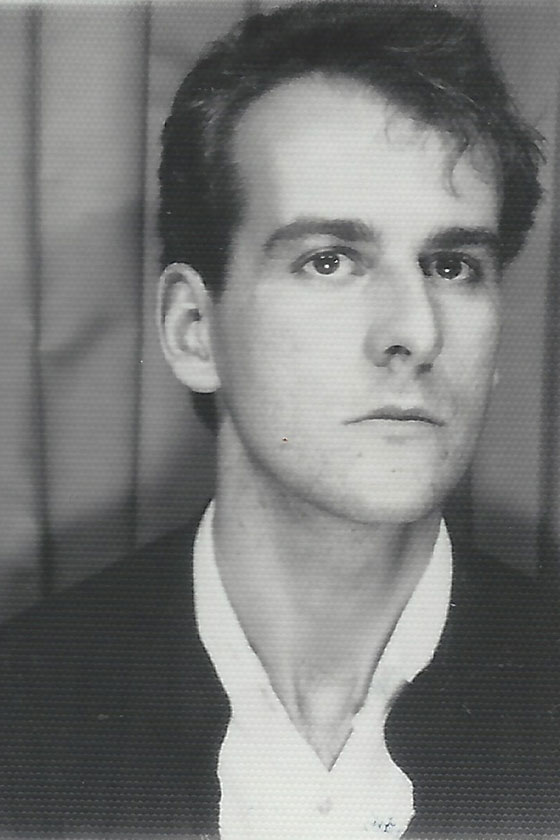

Simon Critchley.

(Photo: Courtesy of Simon Critchley) |

I was working in this factory that was making drugs for diabetics in a town in Hertfordshire, 30 miles north of London. I was 18. My job was to mix these drugs in a huge food mixer, about six feet long with huge paddles inside. And to get all the stuff, you had to get it out in buckets, and the buckets you’d put into sacks, and then you’d give it to the next stage of the process. To get the last of the white powder out, you’d have to put your hand in the machine and push it down the hole. I was bent over, my arm was in the machine, someone turned it on, and obviously I flinched but my arm was caught in the machine by these inch-thick steel paddles. Somehow I wrenched my arm out of the machine so that he hand was almost completely severed. I didn’t feel, in a sense, pain. It was a very strange feeling.

After two weeks in the hospital, I was told by the doctor — I remember this very clearly — that I could keep my hand. Until that moment they had me on so many drugs, I hadn’t even realized that I was probably going to lose my hand. And what saved it was the fact that I was working in a drug factory — this sounds like a kind of episode of Narcos or something — it was a legitimate drug factory, and it was sterile conditions, so I didn’t get an infection. Because if I’d gotten an infection, they’d have to amputate. And that would have been interesting, you know? So I look at people who’ve got limbs missing and I go, “Yeah, that could have been me.”

But the effect was a kind of memory wipe — that was the psychological thing. The trauma of the experience erased my memory. I was a kind of blank slate. I asked my mother or sister, you know, “What happened?” And they showed me photographs and I recognized it as me, but I had no memory. There was a clear break and I still don’t know who that person was from zero to 18.

So now I had to rebuild the memory. Eventually, rather than fill that in with, you know, rock and roll and drugs, I went back into education and discovered philosophy. That time, I was ready for it. It just seemed smarter and more difficult. I’ve always been attracted to difficult things. I went to university when I was 22. I was a working-class kid, just kind of streetwise. I thought I could see through a lot of the people teaching me. But the philosophers I was taught by I couldn’t see through, I couldn’t work out how they were doing what they were doing. And that intrigued me.

I couldn’t physically write for the best part of a year, and I had to relearn to use my hand. And then when I was a student I had to relearn to write every year to write exams — ’cause everything back then was written exams, and my writing was pretty much illegible. And also I was in a lot of pain. So my relationship to pain changed — and my thinking with pain. We think of pain as some kind of problem — it’s not a nice thing to have. But pain can transform. I remember thinking, you know, very clearly in my mind, that I’d never be happy. I thought, I might as well throw myself into studying and teaching because I could help other people who felt a similar kind of anxiety and disturbance, and hopefully help them too.

The first thing that really hit me viscerally was a line in Heidegger when he says, “Anxiety reveals the nothing.” And on one level I didn’t even know what that meant grammatically — what does that mean? But I knew intuitively what was at stake. Because I was suffering from profound anxiety, but it wasn’t linked to a fear of anything. So the first discovery I made, if you like, was making a distinction between fear and anxiety. Fear is always related to an object. So you can be scared of crocodiles or whatever, and if a crocodile is not there then you’re not scared. Anxiety has no relationship to a particular object. Anxiety’s a kind of general mood that one has in relationship to the world. And once you’ve got that, once you’ve made that discovery, then you’re no longer scared in the same way. Right? That’s good. So mostly we misdescribe anxiety as fear and we think that I feel the way I am because I’m scared of this or that or this person or that person. And then if you get rid of that, you realize that this is just what it means to kind of be alive. And to be happy with that, then you can lose your fear.

I thought, in my naïveté, that I could help other people that were suffering with anxiety. That was it. I was suffering with this kind of overwhelming, nameless anxiety and I couldn’t identify it, and I was given, as people usually are, medication. That didn’t work, it just felt like I was living in kind of a bubble. And this realization about anxiety really helped. I thought I could teach people that. And that would be a first step.

****

Critchley’s most recent book is Memory Theater.