|

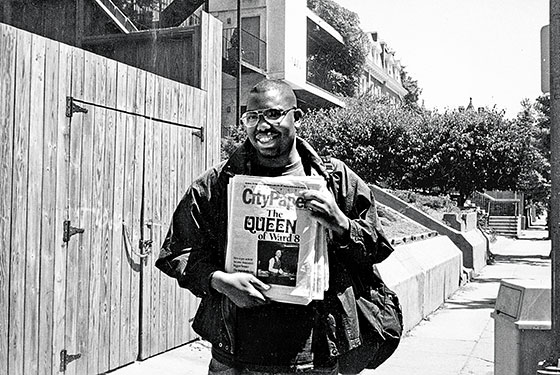

(Photo: Courtesy of Ta-Nehisi Coates) |

I used to read the Washington City Paper, and they would do these long-ass articles, maybe like six-, seven-, eight-thousand-word articles. They were the weirdest articles because they were what we call today longform journalism but they were in that sort of Hunter S. Thompson school, and there would be this mix of first person and reporting. A lot of times, they were writing these long-ass articles about people they clearly didn’t like. But they didn’t just sit like back and write about people; they would go interview the person, they would spend time with somebody they didn’t like. It was very confrontational and aggressive, and there’d be this mix of history and cultural criticism and first person and journalism. It seemed so creative, it seemed like you had so much at your disposal.

I had just turned 20 years old. And — geez, I was so close to school — I mean high school, that’s the crazy thing about it. I was still very much a child in many ways. In some ways I was more mature than other people, in other ways I was very, very immature. One way that I was mature is that I really cared about writing, I cared a lot about it. And I would have written David Carr a letter expressing my interest, and I think I sent him this little chapbook of poetry and three or four articles that I had written for the school newspaper. You just mailed it off, and, you know, you just waited — that’s old school right there, you put it in the mail. And so he called me — somebody from the office called me ’cause there wouldn’t have been email back then. They would have left a message and said, you know, “Hey, this is so-and-so from the City Paper, we’d like to talk to you.” I went in, and I tried to dress as best as I could. And that was not very dressy, but it was okay. I think I had a pair of nice pants, and I remember I had a leather jacket on — I didn’t have like a normal blazer, so I had a leather jacket on — and my little tie. There were no black people in the office. Like none. This is immediately the whitest place I had ever been in my life. Right away. So I get in and culturally, you know, it’s like a different world. I’m looking at these folks, and they’re not even professional, or corporate, like what you see in the movies or on TV. You know, these are like alternative white people, and I had no exposure to alternative white people, like none. I didn’t know what that was. They were all dressed down; I think it was March and they had on shorts. I was like, God, everybody’s in shorts. What’s going on here? They were so, so relaxed. And then I was brought in to talk to David Carr. And David was loud and boisterous, and he was in shorts, and he was charming, even if he was loud and boisterous and aggressive. He’s very likable instantly — kind of crude. He’d yell at you, but he yelled at everybody. I think the only other place you might get that experience is like in athletics. Maybe in the armed services. He said, “Yeah, I got your stuff, and, you know, this poetry thing, we don’t do this, but, you know, I like this. I like that you did this.” And I think looking back on it, what he liked was that I had made it — I think he liked the fact that I had put it together into a book; it’s a little chapbook. That showed initiative. I wasn’t just sort of scribbling things in my room and sending them out. And he said, “Yeah, man, you’re the shit, man. You’re the shit. Why don’t you come do this?”

Erik Wemple was my editor, and he sent me over to Ward 8 to talk to this group of people in this neighborhood called Hillcrest about why they couldn’t get a sit-down restaurant in Southeast D.C. Southeast D.C., at that point, had a reputation as a really poor area of the city, but nestled within there was this neighborhood of Hillcrest that was very middle class, very working class, very nice. And they just couldn’t get services. I didn’t think I could write that story. I didn’t think I was that type of person. There were people at City Paper who did that, and I thought they were better than me, I thought they were smarter. I thought they were naturally better than me, like they had some sort of instinct for something. What I found out — what I discovered at City Paper — was that journalism is a done thing. In other words, there is no real “better than you.” There’s just the story you produced. That’s what it is. Either you repeatedly asked questions or you didn’t. But you made a choice. Someone else might be more curious than you, but the functionality of them being more curious than you is that they just asked more questions. That was a deep sort of lesson — that the winner is the person who keeps asking questions. That’s the winner.