As Michael Bloomberg prepares for his post-mayoralty, his media company is also evolving. For decades, Bloomberg LP saw profits soar by selling just-the-facts journalism and financial information to Wall Street traders. That vision, while still wildly profitable—Bloomberg LP earned $7.6 billion in revenue last year—is now changing. The company is aggressively leasing its terminals abroad even as it is trying to diversify. Last year, Bloomberg spent almost $1 billion to acquire the legal-research firm BNA and spent millions to launch a government-information service called Bgov.

Bloomberg LP began by selling pure information, and its journalism is still heavily influenced by a commodity model. The company’s self-professed mission statement is to become “the most influential” news service in the world. Bloomberg’s agent in this effort is Matthew Winkler, a former Wall Street Journal bond reporter who joined Bloomberg in 1990. Like all Bloomberg staffers, Winkler has an open-air office. “One of the things that Mike bequeathed to us was a culture,” Dan Doctoroff says. “A culture of being highly focused, somewhat paranoid, and we take nothing for granted.”

Like Bloomberg, Winkler can be obsessive and detail-oriented. Winkler’s code is called “The Bloomberg Way,” a 376-page rule book that all new hires are required to study during intensive orientation boot camps. The style was designed to strip all interpretation from the news, leaving behind nothing but facts (one famous rule has it that no sentence should begin with “but”). Winkler says his code is an homage to George Orwell, E. B. White, and Bill Zinsser. “Use one word when two will be good,” he says. Bloomberg journalists are constantly evaluated for their productivity. Reporters earn points for the number of clicks their articles receive on the Bloomberg terminal. “It was well known and is well known that if you write a story about Goldman Sachs, sex, Viagra, Tiger Woods, and Barack Obama, you’d get a huge number of clicks,” a former reporter says. At Bloomberg, the internal computer system monitors employees’ activities. “Anyone in the company can look you up to see if you’re at your terminal,” a former staffer says. “It tells you how long your terminal has been idle.”

In a way, Bloomberg LP is like Google: It has one wildly successful business model (selling data to banks in the case of Bloomberg; search in the case of Google). Efforts to expand beyond the core business of leasing terminals to financial firms have failed to produce similar results. In recent years, Bloomberg has grown through international expansion into emerging markets. But the company faces some challenges. Under CEO for multimedia Andrew Lack, Bloomberg Television has failed to eat into CNBC’s audience. Last year, talks to partner Bloomberg TV with ABC News broke down. Bloomberg has tried to attract stars, including offering CNBC’s David Faber a mid-six-figure deal. Bloomberg also went after the Times’ Andrew Ross Sorkin. Neither could be swayed. Part of the problem is that Winkler remains resistant to adopting some of the entertainment values that could attract an audience. Last year, producers inserted a clip from The Princess Bride into a segment about the wild volatility in the market. “Winkler went batshit,” one person familiar with the matter said. “He wrote out a note saying that we shouldn’t mix fiction with news.” (“I think news should always be about the facts,” Winkler says. “You shouldn’t mix fiction with nonfiction; it’s oil and water.”)

Senior executives have discussed getting out of the domestic-television business, but the idea went nowhere; Doctoroff says they’re staying the course. “It fits into the strategy of broader distribution, which helps us to gain greater influence, which helps us to gain greater access, which helps us to generate market-moving, exclusive content, which helps us to sell terminals, which we then reinvest back in our media properties.”

The Bloomberg-ian obsession with measurement and control has often led to friction as Bloomberg has tried to build out his company. In October 2009, he approved the decision to pay $5 million to acquire Businessweek from McGraw-Hill. Financially, the title was a mess—executives said it may have been losing in excess of $40 million a year, a number that scared off other bidders, including Donald Trump. (“I was shocked to see those numbers,” Trump told me recently. “That thing was a rocket ship going in the wrong direction.”) But Bloomberg wanted the 80-year-old publication. On one level, it was a marketing play: Having the Bloomberg name slapped on the title meant it was now a weekly presence in office parks all across the country, and CEOs of companies far beyond Wall Street would want to grant interviews to Bloomberg journalists. “We bought [Businessweek] because we have 2,000 journalists and they’re writing historically for 300,000-plus customers,” says Doctoroff. “Those customers are a very deep audience, but a very narrow audience. We need to make sure we have broader distribution to reach them so that they are far more likely to talk to us first.”

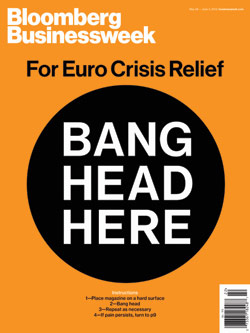

Organizationally, Businessweek would be a major test of Winkler’s control. Shortly after the deal closed, Bloomberg hired former Time.com editor Josh Tyrangiel to edit Bloomberg Businessweek. At first, Tyrangiel’s vision clashed with Winkler’s determination to prevent an erosion of the rigid style he’d demanded all these years. In an early staff meeting with members of the magazine, Winkler made it clear that Businessweek would be governed by the same rules that guided his wire service. “He said, ‘Same product, different packaging,’ ” one staffer in the room recalled. After Tyrangiel ran an article Winkler didn’t like, Winkler critiqued the magazine’s use of anonymous sources as sloppy journalism in a weekly memo to the entire newsroom. Still, in the past two years, Tyrangiel has managed to transform the magazine, to critical praise—though a spokesperson confirms that it is projected to lose some $18 million this year.

Opinion journalism has been an even more complicated challenge—but to Bloomberg a necessary one. “He looked around and saw that a lot of the media properties he reads have editorial voices. Bloomberg didn’t,” his communications director, Howard Wolfson, says. “He thought, Why not? He felt there were too many voices on the extremes. There was a need and an opportunity to fill space in the center.”

Pointedly, Bloomberg decided the venture would be housed in the offices of his foundation, independent of Bloomberg News. Bloomberg’s opinion arm was christened Bloomberg View, and Bloomberg personally hired Jamie Rubin, a former State Department spokesperson, to run the View alongside the New York Times’ former deputy opinion editor David Shipley. Bloomberg was vague in his directions, telling staffers that “as long as what they published was “pro-capitalist, pro-freedom,” he’d have no issues, one editor recalls.

A fault line soon opened between Shipley and Rubin. There were personality differences: Shipley is a measured manager, Rubin can be brusque and domineering in meetings. Colleagues were turned off when Rubin invited Admiral Mike Mullen for lunch and excluded certain staff members. Rubin didn’t like the townhouse’s open-plan offices. When his request for an office was rejected, he asked if higher cubicle walls could be installed around his desk. Ultimately, he often worked in a conference room.

Contrary to what Rubin may have wanted, View was beginning to look more newspaper op-ed page than think tank. In June 2011, Rubin pushed to publish an editorial by Stuart Seldowitz, a former State Department official who had been Rubin’s sole hire, that advocated a tougher line on Pakistan than the Obama administration was pursuing. The article sparked a battle between Rubin and his allies and the journalists, who felt it was too aggressive. The editorial was published, but by that point, Rubin and Shipley’s relationship was beyond saving. The journalists saw Rubin as an example of the mayor’s promoting from within his social circle (Rubin’s wife is Christiane Amanpour). “Jamie was referred to as a cocktail-party hire,” one staffer says.

Rubin and Seldowitz were fired last September. “I wish the mayor the best and hope his effort succeeds,” Rubin, who is now an economic adviser to Governor Cuomo, wrote me in an e-mail, “but from my experience there, without some major changes, I don’t believe it will ever be the influential platform he envisioned.”