In the hours after Hurricane Sandy sucker-punched New York and moseyed away, leaving a ring of filth, death, mold, and crumpled houses, the lesson of the storm seemed clear, if you were in a moralizing frame of mind. We had disrespected the sea—built too close, too low, too blithely—and been punished for it. All those glittering apartment towers with their whitecap-flecked views were a mistake of the market. When the first waves hit, New Yorkers suddenly understood topography they had always ignored, and any neighborhood with the word “heights” in its name (Crown, Prospect, Washington) now had a comforting ring. The storm made it obvious why people had avoided soggy landfill, at least until low-lying factory areas like Tribeca were magically made luxurious. In the future, surely real-estate ads would boast of a property’s elevation.

Seven months later, Mayor Bloomberg is doubling down on the waterfront metropolis. Even as the clock runs out on his mayoralty, last month he released a valedictory manifesto with a dry title (“A Stronger, More Resilient New York”) masking an urgent cry. New York has too long and tangled a relationship with the waterfront to retreat upland or cower behind seawalls, the report declares. Compiled by a battalion of specialists at the mayor’s behest, the 438-page analysis works its way around the city’s 520 miles of fantastically varied coastline, proposing a $20 billion array of treatments. Dunes in the Rockaways, levees in South Beach, removable walls on the East Side of Manhattan, hardened power stations, flood walls, wetlands, bulkheads, esplanades—the proposals vary sometimes block by block.

Behind that hyperrational menu of engineering options is a technocrat’s love letter to the maritime city. The charts and recommendations amount to a statement of faith that the waterfront is the city’s future as well as its past. Partly, it’s a reaffirmation of long-standing policy. Most of the major developments that Bloomberg has championed and that are now in the works—Hudson Yards, the Cornell tech campus on Roosevelt Island, Willets Point, Riverside South, the Con Ed site, Hunters Point South—flank the East and Hudson Rivers. But even if he did not have his legacy on the line, Bloomberg grasps an essential truth: This is a city built not just near the water, but over, under, and in it.

Glance at a map of New York, and what you see is a lot of blue, ringed by a piecrust of boroughs. This is a largely liquid city, a stunningly obvious fact that for decades was almost forgotten and that we’re only just beginning to remember. In 1877, Harper’s Weekly took its readers on a tour of East River landmarks, pointing out “the public buildings on Randall’s, Blackwell’s, and Ward’s islands, Hell Gate, the Hunter’s Point oil-works, the Navy-yard, the Drydock, the massive masonry of the great bridge, and the crowds of shipping down to the beautiful Battery and historic Castle Garden.” A century later, in 1977, that same itinerary would have led past forgotten wastelands, rotting structures, crumbling bulwarks, and vacant piers. That period of traumatic neglect haunts every page of the Bloomberg plan.

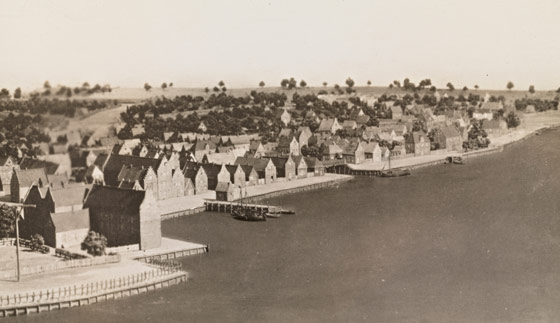

New York’s relationship with its waters is a long and crazy romance, fueled by manic energy, gilded dreams, violence, abandonment, and elated rediscovery. The story begins on a claustrophobic block of Pearl Street between Broad and Whitehall Streets, shadowed by office towers on all sides. In the seventeenth century, this was both the edge of New Amsterdam and its center. The town’s greatest house, Peter Stuyvesant’s two-story mansion, sat beside serried shops, wooden homes, taverns, and warehouses. Ships moored at the sole wooden dock poked into the East River. Sailors unloaded their cargo, hauled it across the dirt road to the Dutch West India Company, and lifted it into the upper-level storeroom by a pulley fastened to the brick façade. Colonists from a country under perpetual threat of drowning knew to keep their valuables raised.

For 350 years, that process—moving stuff in, working on it, and shipping it out—fueled the city’s growth. In 1730, Nicholas Bayard opened North America’s first sugar refinery on Liberty Street, a momentous event not just because it introduced New York children to the joys of commercial candy. Ships carrying sugar from the Caribbean also brought other fragrant cargoes: cocoa, molasses, limes, tobacco. Sugar and shipping produced great wealth and establishments in which to spend it: Watchmakers, booksellers, clothiers, and other ateliers hugged the docks.

One of the startling aspects of Sandy was the collision of prosperity and disaster. Urban pioneers with million-dollar views watched the storm ravage their streets. Art galleries took a beating. It’s a drama that has played out many times before, because the waterfront was always where the money was. If Madonna had stepped off a vessel at Burling Slip around 1800 and asked to be taken “to the middle of everything,” she would have been pointed toward Tontine Coffee House, at the corner of Wall and Water Streets. Built in 1793 by the city’s first stockbrokers as a place to do business in, it also served as an inn, a dining room, and a bazaar where dealers traded whatever was for sale: molasses, investments, political influence, news, and slaves. “The steps and balcony were crowded with people bidding, or listening to the several auctioneers,” a visitor reported. “The slip and the corners of Wall and Pearl-streets, were jammed up with carts, drays, and wheelbarrows; horses and men were huddled promiscuously together, leaving little or no room for passengers to pass … Every thing was in motion; all was life, bustle and activity.” The frenzy accelerated after the 1825 opening of the Erie Canal, when New York Harbor became a vestibule for all America. Soon, tides of bankers, brokers, lawyers, bookkeepers, and politicians sloshed daily between the docks and the grand new marble Merchants Exchange on Wall Street.

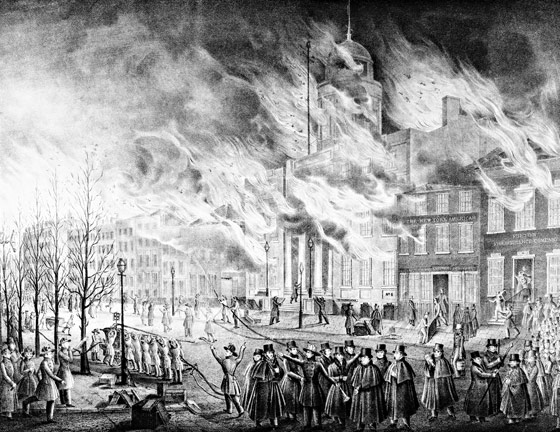

Then, one December night in 1835, a security guard smelled smoke. In one of the many jammed warehouses downtown, some scrap of wealth awaiting shipment went up—a bale of cotton, maybe, lit by a dropped cigar or a spilled oil lamp. In minutes, the frigid wind off the harbor tossed the flames from window to window and roof to roof. Firefighters flailed; pumps seized up and near the shore the East River was frozen solid. Crowds frantically hauled valuables to the Old Dutch Church, a solid brick building. It was said that when the fire swept into the nave, feeding on pews and salvaged ledgers, someone rushed to the doomed organ loft and played Mozart’s Requiem as the flames rose. More likely, the sound was hot air rushing through the pipes, producing eerie unmanned blasts. When the fire finally burned itself out on the second day, lower Manhattan was a charred hellscape. The Merchants Exchange and the Tontine Coffee House were gone. Dozens of ships, cut loose so the flames wouldn’t leap aboard, drifted offshore like so many Flying Dutchmen.

Today, as we tally the mountainous task of preparing for future onslaughts, it’s worth reflecting that New York has had to retool far more radically in the past. After the 1835 fire, with most of the seventeenth- and eighteenth-century city wiped out, New York reseeded itself. Businessmen built a more lavish and durable set of storehouses, banks, and exchanges. Fire codes were rewritten. Water was piped in from upstate. Two days’ total destruction were a blip when what mattered most was that the flow of goods, people, and credit remain unobstructed. Just three years after the fire, in 1838, the S.S. Sirius chugged into New York Harbor, eighteen days out from Ireland, winning a transatlantic race with the Great Western. The era of the steamship had begun, and the pace of commerce accelerated again.

Just as environmentalists are scrutinizing the Bloomberg plan to gauge the collateral damage to nature, so in the nineteenth century some people felt that rebuilding was a greater calamity than the fire itself. In 1844, Edgar Allan Poe took a skiff into the East River and was gloomily entranced by the wilds of midtown. “The chief interest of the adventure lay in the scenery of the Manhattan shore, which is particularly picturesque,” he reported. But, he continued, “I could not look on the magnificent cliffs, and stately trees, which at every moment met my view, without a sigh for their inevitable doom … In twenty years, or thirty at the farthest, we shall see here nothing more romantic than shipping, warehouses, and wharves.” You can sense the same struggles between the conflicting needs for construction and conservation in the pages of the post-Sandy report, where new East Side towers jostle with restored wetlands and rocky shores. Commerce made the waterfront buzz, and also made it infernal. Jobs and pollution, liveliness and crime, prosperity and decrepitude, labor and leisure—all these opposites gave the industrial waterfront its schizophrenic allure.

As the island became more urbanized, it produced immense quantities of rubble and refuse. In 1811, the Commissioners’ Plan decreed that Manhattan would grow along a rectilinear grid, so hills were leveled and cliffs blasted away to make the terrain conform to the map. As the population grew, the tonnage of trash exploded: Between 1856 and 1860, its volume increased 700 percent. Huge loads of ash, offal, manure, dead horses, and household garbage were carted to the water’s edge and loaded onto floating “dumping boards” and into the shallows and slips, where they gradually became alchemized into real estate. The slow process haloed the city in stink, but in the long run it proved to be the most profitable form of recycling. Poe’s picturesquely irregular shoreline grew flat, straight, and smooth, the perfect staging ground for a great economy—and for wrenching social tumult.

The cogs that kept the intercontinental mercantile machinery running were the longshoremen, brave and powerful workers who spent their days heaving 300-pound sacks and were periodically crushed beneath tumbling loads of cargo. It was brutal work, but it was regular. It was also one of the few jobs open to African-Americans, making the waterfront one of the only areas where whites and blacks lived side by side. Proximity did not lead to racial harmony, though. The all-white Longshoremen’s Association complained that black dockworkers were driving down wages; shippers periodically hired them as strikebreakers. In March 1863, a rampaging white gang hunted down black porters, stevedores, and carters. When the Draft Riots broke out that summer, resentment spilled over into the waterfront’s racial turf battles. Black longshoremen were beaten and lynched, their bodies hurled into the river. Intimidation worked. By the time the chaos abated, the Manhattan waterfront was almost totally white, as blacks fled to Brooklyn and New Jersey.

Eventually, they returned, of course. No horror was enough to weaken the magnetic power of trade, so the waterfront became ever more frightening, chaotic, and thrilling. By the mid-nineteenth century, logs floated down from Maine were herded toward the Steinway piano factory in Astoria. Floating grain elevators bobbed back and forth from dock to train depot. The waterways were so congested that you could practically have hopped from deck to deck clear across the Hudson. The traffic crammed warehouses with exotic goods: A list that appeared in Harper’s in 1877 includes half a million pounds of annatto (“for coloring ‘country butter’ ”), 64 million pounds of brimstone (“destined to regions infernal?”), and 170,000 pounds of opium.

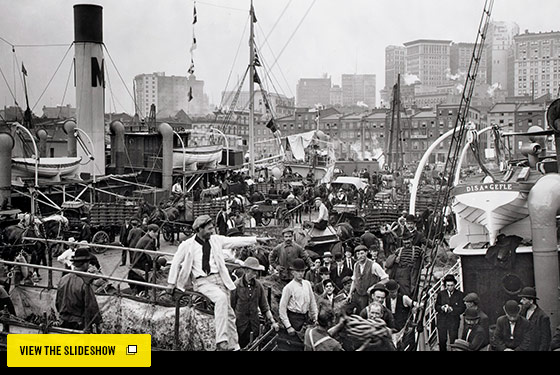

As authorities tried to bring order to the waterfront, shippers turned it into a jumble of makeshift, foul piers. Cattle brought by train from the West were driven through the streets, onto vessels bound for England. Passengers and pickpockets milled among the horse-drawn carts that stood waiting for their loads. Freight trains huffed along Tenth Avenue, regularly crushing wagons and killing pedestrians.

To these industrious throngs, the notion that New Yorkers would one day trot along the waterfront for their health and pleasure—or that the rich would live there voluntarily—would have seemed absurd. Waterfront real estate was too necessary to allow for leisure. Drinking was welcome, though. At the eastern end of 57th Street, an open-air beer garden, the Felsenkeller, had an orchestra and bowling tournaments. Other such establishments were far less wholesome. Disembarking sailors had only to stumble a few yards into back-alley taverns that regularly changed sign and address but always purveyed the same fetid atmosphere and cheap rum. In his impressively morbid survey Low Life, Luc Sante tells of Sadie the Goat, a two-bit Hudson River pirate who wore around her neck the ear she had lost in a bar fight, and of the Fourth Ward Hotel, which “had convenient trapdoors through which corpses could be disposed directly into the East River.”

While industry colonized the shores, right-thinking citizens agitated to make the waterfront serve a social function, too. Floating baths, two-story structures built around a courtyard of river water, provided places for the poor to cool off. But recreation required a battle. In 1866, after decades of failed attempts to preserve various shoreline patches as parkland, Upper West Side property owners managed to get the cliffs beneath their houses set aside for Riverside Park and gave the job of designing it to Frederick Law Olmsted. But the residents’ desire for picturesqueness collided with the need for a flat zone where the city’s dirty work could take place. In the turn-of-the-century views painted by George Bellows, elegantly dressed West Siders promenade along winding paths, gazing appreciatively across the icy Hudson at the Palisades—and paying no attention to the clanking strip of train tracks, moorings, and dumps immediately below.

It was the ocean liner that finally brought some class to the West Side. The city, embarrassed that visitors who crossed in modern luxury disembarked in squalor, finally overhauled a tumbledown stretch of shacks and rotting docks between 15th and 23rd Streets. Warren and Wetmore, the architects of Grand Central Terminal, designed a suite of modern enclosed piers faced in noble granite. In 1910, the Times reported the project’s cost at $25 million (more than $600 million today) and declared its completion “a matter for general congratulation.” The Lusitania and the Mauretania dropped anchor in Chelsea. The Titanic was supposed to do the same.

Maybe it’s just the foreshortening effect of looking back over a long history, but the swings in the waterfront’s fortunes seem to get wilder and more frequent as you move into the twentieth century. Good and bad times overlapped, and it’s astonishing how little each affected the other. Because it was so useful and also picturesque, the waterfront was a battleground between the bucolic past and the industrial age. The illustrated book The East River contains a surreal pair of photographs from the twenties: One shows a family of farmers on hands and knees, crouched over furrowed fields in the Bronx near Soundview Avenue; the other shows a factory just across the East River in College Point, spitting out Sikorsky aircraft. Even during the Depression, as fewer ships tied up or rolled off the drydock, and stevedores huddled around dockside fires waiting for jobs that never came, the eighteenth century and the twentieth were working out some kind of coexistence.

In 1938, a murderous hurricane threw itself at eastern Long Island, erasing dunes, splintering homes, and taking a swipe at the city before rampaging through southern New England. If ever a weather event should have nudged a complacent area into protecting itself from a potentially hostile ocean, that storm would have been it. But that time, there was no plan, just the tacit assumption that the waterfront and the weather would have to call a truce. Hamptons mansions replaced modest houses, and the Manhattan seawall was patched up, to cries of “Whaddayagonnado?” Just as the world was exploding into war, New Yorkers cultivated a feeling of invulnerability that bordered on the delusional. A few weeks after Pearl Harbor, a German U-boat snuck past Coney Island and found the Manhattan skyline merrily illuminated, silhouetting ships and making them that much easier to torpedo. The career of the glamorous French liner Normandie—a glamorous Art Deco palace, as long as the Chrysler Building is tall—ended just as sloppily. In 1942, the liner was moored at Pier 88 (at West 48th Street), undergoing conversion for military use, when sparks from a welder’s torch started a fire. A few hours later, she keeled over, settling into the river sludge, where she lay rusting till the war ended. It would have been hard to find a more vivid omen.

A few weeks ago, when Mayor Bloomberg released his resiliency report, he held the press conference at the Brooklyn Navy Yard, an attempt to show that the waterfront of the future is not just a pleasure zone but an old-fashioned engine of manufacturing jobs. That hope for the future rests on an evocation of the past, since the glory days of the working waterfront came during World War II. Convoys steamed through the harbor. Governors Island teemed with soldiers on their way to Europe. The Navy Yard employed 70,000 people. When the war was over, New York was left with a magnificent maritime machine, the world’s busiest port, an industrial base on overdrive, and a plentiful supply of brawn.

But by then the city and the water had started to pull apart. Even before the war, Robert Moses had laid down a concrete moat of elevated highways. He cleared entire neighborhoods that he deemed slums and exiled their populations to low-lying—and low-value—waterfront areas. As the country demobilized, the working waterfront turned into a separate universe run by a shadow government. In 1948, the New York Sun reporter Malcolm Johnson wrote a Pulitzer Prize–winning series that later inspired Elia Kazan’s On the Waterfront. The movie focused on one gravel-mouthed young man (played by Marlon Brando), but Johnson was more impressed with the enterprise’s imperial scale. “Here, in the world’s busiest port, with its 906 piers, 100 ferry landings, 96 car-float landings and 57 ship buildings, drydock and repair plants, criminal gangs operate with apparent immunity from the law,” he wrote. “These gangs are well organized and their control of the piers is absolute. Their greatest weapon is terror.”

Isolation created a tangible gulf between upland New York and its increasingly mythologized edge. In Arthur Miller’s 1955 play A View From the Bridge, Alfieri—the character through whom the story is told—sketches the stevedore’s habitat of Red Hook: “This is the slum that faces the bay on the seaward side of Brooklyn Bridge. This is the gullet of New York swallowing the tonnage of the world.”

From the seventeenth century to the mid-twentieth, whenever it seemed that the bond between the port and the city had reached its climax, the intensity made another leap. Fire, violence, economic depression, accidents, and planning blunders couldn’t damage that relationship for long. And yet the love did die. What finally killed it was a banal but transformational invention: a stackable, standardized steel box, eight by eight by twenty feet. The shipping container could be hoisted from freighter to wharf by a crane, then dropped on a flatbed truck or train car without unpacking. The system needed fewer hands but much more maneuvering room than the old piers could offer. Shipping moved to New Jersey, jets displaced ocean liners, and, just like that, the New York waterfront was finished.

The piers quickly devolved into a wilderness of rusting gantries and shattered concrete that nobody wanted. Nobody, that is, except those who had nowhere else to go. In his novel Nocturne for the King of Naples, Edmund White describes the piers in the seventies, abandoned except by a furtive night crew of gay men. “For me there was the deeper vastness of the enclosed, ruined cathedral I was entering. Soaring above me hung the pitched roof, wings on the downstroke, its windows broken and lying at my feet … I smelled (or rather heard) the melancholy of an old, waterlogged industrial building.”

Virtually every old urban port in the world suffered the trauma of containerization and has been groping for some way to heal. Amsterdam is turning piers into the foundations for apartment buildings. Oslo has perched an opera house above its fjord. Hamburg is rolling out a huge multidecade development. Barcelona created a beachfront strip of outdoor leisure. Hong Kong is mired in perpetual planning. What makes New York’s waterfront unique is that it is so long, jagged, and varied. Consequently, so is the story of its reclamation, which has taken innumerable forms: restoring the marshes of Jamaica Bay, populating Battery Park City, rebuilding a popular restaurant at the Dyckman Street Marina, lining the rivers with bikeways, nurturing the Navy Yard, adapting old ocean-liner piers for cruise ships, installing ferry stops, putting in skate parks, cleaning up the Bronx River, and preserving abandoned warehouses.

By the early nineties, all that was left of Warren & Wetmore’s 1910 piers was a rusted skeleton and a history of good intentions. Then Roland Betts, a co-owner (along with George W. Bush) of the Texas Rangers, launched a plan to convert them into a vast sports facility. At the time, just crossing to the river side of West Street was an adventure; driving golf balls toward New Jersey from the Lusitania’s old dock seemed like a lunatic fantasy. Nevertheless, Betts’s Chelsea Piers opened in 1995, catalyzing an entire new neighborhood. Hudson River Park snaked around it, Tenth Avenue became a fine address, and the warehouses turned into the world’s preeminent art district. On a drive up the West Side, the past fifteen years’ new buildings click by almost too quickly to count: the trio of Richard Meier towers at Perry Street, the behemoth that replaced the old Superior Ink factory, the sailing ship of an office building that Frank Gehry built for Barry Diller, glass towers flanking the High Line. The lawless waterfront became a backdrop for the lives of the affluent. Then Sandy hit on October 29, 2012, and five feet of saltwater raced through the Chelsea Piers complex, across West Street, and into the galleries.

In the early nineties, I lived in a landlocked part of Queens, only vaguely aware of the water. I crossed the East River by bike daily, but I saw it mostly as a twinkling grid through the steel-grate roadway of the Queensborough Bridge. On some days, a damp, fishy breeze sneaked through our neighborhood, bringing a whiff of the Keys or the spray from a distant Atlantic storm. But despite these reminders, the presence of water in the city struck me as an archaeological relic. All I could see of the riverfront were stretches of oily concrete and sad sheds behind a chain-link fence. I knew that a canal still lurked beneath Canal Street, and that pleasure boaters sailed in Pelham Bay. On weekends I might make an excursion to Coney Island, where ghostly broadcasts of ancient Dodgers games drifted across the dilapidated beach.

Twenty years later, the New York that’s still reeling from Sandy is a much more maritime place, and the waterfront is shockingly … pretty. These days, you can paddle from one kayak launch to any of 46 others, canoe down the Bronx River, bike for miles along the Hudson, and commute by ferry from Williamsburg to the base of Wall Street. We have discovered the pleasures of conducting our leisure activities—skateboarding, sunbathing, drinking, watching movies, even swinging on a trapeze—within sight of boat traffic.

New York is besotted with its waterfront, or was, until Sandy made it clear that the city resembles the shipwrecked boy in Life of Pi, sharing a lifeboat with a Bengal tiger. Like the beast, the water is beautiful, alluring, and vicious. The storm demonstrated that we can’t get away, we can’t confine it, and we can’t beat it back. As the Bloomberg report makes clear, the only option is a cautious love.

New Amsterdam, a port town from the start: 1660. Photo: Courtesy of Museum of the City of New York

The city, ruined, faces rebuilding: 1835. Photo: Museum of the City of New York/Corbis

Commerce dominated the waterfront in 1905. Photo: Bettmann/Corbis

Charm twinned with reek: Rain on the River, by George Wesley Bellows, 1908. Photo: Courtesy of Jesse Metcalf Fund RISD Museum

Depression-era glamour: the Normandie, 1935. Photo: Gallery Stock

A tough, corrupt workplace: 1937. Photo: Courtesy of Museum of the City of New York

The last days of the longshoreman: 1954. Photo: Robert F. Sisson/National Geographic/Getty Images

Abandoned, then adopted: Pier 51, 1978. Photo: Shelley Seccombe

Leisure trumps all: Hudson River Park, 2012. Photo: Keith Bedford/Reuters/Landov

Leisure trumps all: Hudson River Park, 2012. Photo: Keith Bedford/Reuters/Landov