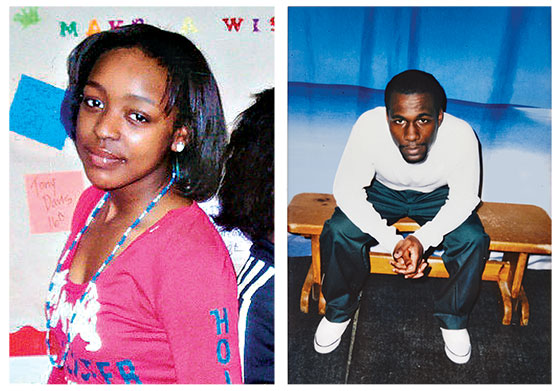

Sahiah Davis and Nathaniel Walcott crossed paths a number of times during childhood, but the last came on April 25, 2011, the night she shot him. They were both 16 and lived in Brownsville, the Brooklyn neighborhood where their parents had also spent much of their lives. Nathaniel was on a bicycle, in search of something to eat. Near a playground on Bristol Street at around 11 p.m., Sahiah and several boys stepped toward him.

Sahiah was five-nine and still growing, all limbs and shoulder blades, with a heart-shaped face and a straightened Afro that crested in a row of bangs. She liked dancing and double Dutch, and in ninth grade played on her high-school basketball team. Her father, James Davis, called her “the Kobe Bryant of Westinghouse,” the vocational school in Downtown Brooklyn. She was known as “Oozi,” which everybody thought sounded like “Uzi” but which her parents insisted was an innocent sobriquet, derived from the very moment she entered the world.

“She wasn’t named for no gun,” her father said. “She was Oozi because when her mother had the C-section, I seen how our daughter ooze out of her belly.”

Nathaniel, for his part, went by “AC.” “Those were the only letters he knew when he tried to sing the alphabet when he was little,” his sister LaToya explained. He was handsome like a TV actor—warm eyes, optimistic countenance—and crazy about cooking shows on TV. “He really thought he was a chef,” LaToya said. “He specialized in breakfast: weirdo omelettes, pancakes with Fruity Pebbles crushed in the batter.”

AC and LaToya were the youngest of five siblings taken in by Charles and Delores Walcott, a tailor and a retired juvenile-correction officer who had already raised several children of their own in a narrow, two-family house on Grafton Street. To the kids’ friends, their living room was a marvel of resourcefulness, paneled with mirrors and full of exotica like the giant white-marble statue of a Borzoi salvaged from sidewalk refuse and dozens of Ghanaian paintings Charles purchased and lugged through Customs decades ago.

Sahiah and AC attended different schools but had known one another since they were 7 or 8 years old. That was when her babysitter, who was dating one of AC’s older brothers, brought her along on visits to his house. And by middle school, the two had similar problems. “She had a short temper,” Sahiah’s father said. “She’d fight a lot. You know how girls are.” AC, his sister said, “was spoiled—the baby. When things didn’t go his way, he tended to act out.” At 14, he was expelled from P.S. 327 for getting in fistfights with other kids and with teachers. A court remanded him to Lincoln Hall Boys’ Haven, a reform school in upper Westchester County. “He had more fun in two years there than here,” LaToya said. “He’d bring home wooden stuff he made in shop. He learned how to cut hair, doing fades or shaving words into the side of his friends’ heads.” Still, he missed home and came back on weekends as much as he could get away with.

“It sounds crazy, but he couldn’t resist the pull of Brownsville,” LaToya said. “This place was all he knew.” When Sunday nights rolled around, he’d hide at his best friend’s apartment and try to go AWOL from the return bus.

At 15, AC joined a friend’s neighborhood gang called Hoodstarz. Sahiah was also a member, but by 2011 she had left to run with a different crew, the Wave Gang. Their friends think her switch had to do with a new boyfriend who was in the Waves, and that, to make good on it, she decided to shoot one of her former allies from Hoodstarz.

So it was that AC, home for Easter break, encountered Sahiah as he tried to ride his bike down Bristol Street.

“Cho!” he yelled out to her.

“Woo!” she and the boys with her replied.

Any Brownsville teenager who happened to hear the exchange would have immediately understood. “Cho” was the Hoodstarz greeting, the equivalent of AC flashing a gang sign; “Woo” was the Wave Gang’s code word. Sahiah and the Waves were telling AC that they did not come in peace.

They quickly surrounded him. She held a gun close to her midsection like a desk worker with a coffee mug and fired at AC. A bullet entered his back sideways and ripped forward through his torso, destroying several organs, according to his autopsy.

“He was trying to … ride off, but it looked like his foot went off the pedal,” a witness later testified. His body fell to the ground.

Stories about the killing appeared in the tabloids the following day, with no details about a potential suspect—an unknown gunman, according to the police. An accompanying photo showed AC’s bike, a pink hand-me-down from his sister, laid out on the pavement and festooned with yellow police tape, its front tire sticking up in the air. Not long afterward, investigators came across the picture again in a Facebook post by a boy who lived in an apartment building considered Wave Gang turf. Beside the photograph of the bike were comments:

AC BUM ASS BIKE

LOLS #Dead

Brownsville, where AC was shot off his pink bicycle, is about a 45-minute ride from Manhattan on the train. It’s a kind of walled city, its uniquely insulated and canyonlike aspect created by the public-housing buildings that occupy the horizon in every direction. Brownsville has 18 subsidized-housing complexes consisting of some 118 buildings, from Tilden’s vertical, Soviet-style campus (eight 16-story buildings comprising 998 apartments) to the relatively low-rise and low-density sprawl of Brownsville Houses (27 buildings of six stories each, 1,319 apartments).

About a third of Brownsville’s households are in public developments—the highest concentration of subsidized housing of any neighborhood in the country, according to the nonprofit Community Solutions. “There are 10,000 units of public housing in Brownsville’s two square miles,” says Rosanne Haggerty, the founder of the agency, which recently established a presence in Brownsville. “In all of Los Angeles, there are about 6,800.” As much of Brooklyn and Queens has boomed, Brownsville has stayed the same. “Gentrification? Forget about it,” says James Brodick, the director of the Brownsville Community Justice Center. “There isn’t even a place to sit down for a cup of coffee in Brownsville.”

And Brownsville, per capita, has by far the highest homicide rate in the city. Over the past six years, the NYPD’s 73rd Precinct—which occupies most of Brownsville—has averaged about 23 murders annually, more than any other except for adjacent East New York (which posts a slightly higher number but has more than twice as many residents). This year, through the middle of May, more people were shot in Brownsville than in all of Manhattan.

The most surprising thing about Brownsville’s endless waves of killing is that many of the victims, along with many of the perpetrators, are children. “The kids keep getting younger—they start at 12 and 13,” says Lieutenant David Glassberg, who ran the NYPD’s Juvenile Robbery Intervention Program in Brownsville from 2007 until this year. “The youth gangs are the reason the Seven-Three is at the top.”

These gangs aren’t cut from the same mold as the drug-dealing enterprises of just a decade ago. They’re cliques of middle- and high-schoolers, divided by block or housing development, who, unlike their forebears, don’t see what they’re doing as a ticket to someplace better. “It was very strange when we realized the kids’ motivation has nothing to do with trying to make money,” says Marc Fliedner, an assistant district attorney in Brooklyn, who has led several investigations of Brownsville’s gangs. “It’s just territorial nonsense. ‘You’re from another building, so I hate you.’ ”

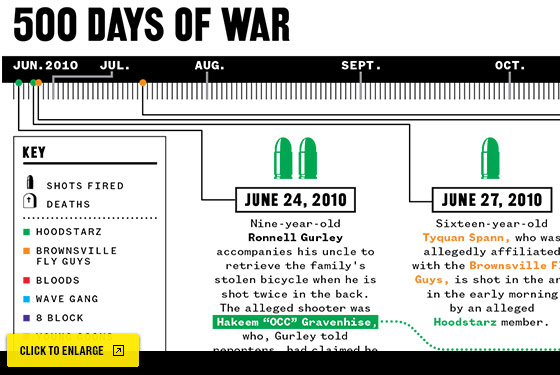

A few years ago, detectives began to focus on a particularly lethal, and vocal, feud playing out along the Mason-Dixon Line of Rockaway Avenue, between the Wave Gang (whose name was inspired by the Adidas logo, and whose members come from the Langston Hughes projects and Brownsville Houses) and Hoodstarz (who reside in or near the blocky, modular units of Marcus Garvey Village). In a little less than two years, the two gangs have accounted for at least six homicides and wounded nearly 40 more victims. More recently, there have been several deaths that police believe may be related. Both the Wave Gang and Hoodstarz were given to weighing in on Facebook and YouTube after each shooting, in patois updates that the police were quickly able to divine and monitor. Hoodstarz called it “going to the beach” when members walked through Wave Gang territory. When one shot a Wave, he said he “clapped him off the surfboard.” To the Waves, shooting a Hoodstarz member—or an “actor”—was “lining you out.”

Brownsville’s gangs are constantly changing their names, merging with others, and splitting off. As it was for Sahiah, a friend one day can be an enemy the next. Some iterations of Wave Gang include Pretty Boy Gang (P.B.G.), Money Gang, Nookie Gang, Smoove Gang, and F.A.F. (“Final Four Tha Fuck Up,” according to a post on YouTube). Hoodstarz has at times been known as 180 Crew and Addicted to Cash (A.T.C.). Other gangs include Brownsville Fly Guys or Brownsville Fresh Gangsters (B.F.G., either way), Bully Boyz, Keep Back Crew, Square Off Crew, Very Crispy Gangsters, Young Guns, 8 Block, Money Gang, Loot Gang, and Yaw Gang. The girls who hang out with the Waves have their own gang, which has at times been called Money Gang Ladies and the Pretty Gang. Some of the kids’ nicknames are Bam Bam, Ruger, Youngblood, Spaz, ’Spect, Peanut, Banga, Slice, Ty Black, Guapo, Birdcage, Murda, Sumo, Uncle Head, Kill Will, and Cereal No Milk.

What it means to be in the gangs—and what constitutes actual gang activity—remain loose concepts. In court recently, when one of the Waves was asked how he joined, he answered: “Just hanging out.” When another member was questioned about what the gang’s purpose was, he answered, “Just used to chill.”

Prosecutors and detectives still don’t know when the battle of Brownsville started or what it was over. Some think it grew out of a perceived slight at a dance-hall party in one of the warring projects, whose turf is separated by about ten blocks. But the authorities did establish a connection to the current group of principals by the summer of 2010, when a series of shootings, allegedly by Hoodstarz members, wounded two associates of the Brownsville Fly Guys (a gang aligned with the Wave Gang). In October, one of them died from the injuries.

Two days later, in what was likely B.F.G. retaliation, the purported Hoodstarz leader, 16-year-old Hakeem (“OCC”) Gravenhise, was ambushed in front of his apartment building with a fatal barrage of gunfire. His mother witnessed the shooting. There have been no arrests in his murder.

When Sahiah quit the Hoodstarz to join the Wave Gang, it was no small betrayal—especially when she proved the seriousness of her intentions by taking out AC. But the Brownsville population at large felt increasingly threatened by the Hoodstarz’s next two salvos, in the summer of 2011: Hoodstarz members allegedly shot one Wave Gang member but also hit five others identified by the police as bystanders—three teenagers (one of whom died) and a 37-year-old man and his 9-year-old son.

The Waves also shot people who weren’t their intended targets. Their alleged leader, 19-year-old Andre Moore, carried out three shootings, hitting a 29-year-old woman and a 16-year-old girl, both of whom were bystanders. And on July 23 he fatally shot 21-year-old Marlon Riley, who was not known to have been a Hoodstarz associate.

Andre, whose friends call him “ ’Spect,” is one of seven children born to Sharon Moore and Dupree “Powerful” Dunbar. Andre’s mother describes her son as “a good boy” and said that one of his teachers told her she was looking at “a future mathematician.” He fell behind at Frederick Douglass high school, she said, though only because of poor attendance. “All the kids from Howard Houses were picking fights with the boys from Langston Hughes,” she told me. “It made him uncomfortable, and I found out he stopped going.”

According to police officers who have known Andre since he was 12, his involvement in the Wave Gang began at around 17 and quickly escalated. While he was growing up, his father did five stays in prison and was reputedly a gang member. (His convictions over the years have involved weapons possession, robbery, and conspiracy.) One of Andre’s younger brothers also joined the Waves.

“Powerful’s a big influence on that household,” Lieutenant Glassberg says. “He’s O.G., talking about street cred and defending your turf. He wants his boys to be like him.”

Marlon Riley’s family, meanwhile, has stressed at every turn that he could only have been an unintended target. “Marlon never wanted anything to do with gangs,” his mother, Arlene Townsend, told me. “After he got shot, I started hearing it was mistaken identity and Andre Moore thought my son was another person.”

But Marlon grew up in Hoodstarz turf, in a second-floor apartment on Tapscott Avenue, though his mother moved with him to the Bronx when he was 16 and a good friend of his was fatally shot. “I tried to get him away from Brownsville trouble, but he would go back because he was lonely,” Arlene said. “I wanted a boy so badly. When he was born, I said, ‘Oh God, thank you.’ It was like I could conquer the world.”

On January 17, 2012, more than 50 officers from the NYPD fanned out through Brownsville early in the morning to arrest dozens of residents whose ages ranged from 15 to 21. Two days later, the Brooklyn district attorney’s office announced the indictment of 43 youths from Wave Gang and Hoodstarz in a sweeping case the prosecutors were calling Operation Tidal Wave. Charges included murder, attempted murder, robbery, and conspiracy, and 35 guns were seized from the kids.

Sahiah Davis, the only girl named in the takedown, was charged with the murder of Nathaniel “AC” Walcott, and Andre Moore was charged with Marlon Riley’s murder. Linked by their Waves affiliation, they stood trial together in the final weeks of 2013. A second murder trial, of two alleged Hoodstarz members, is scheduled for later this year.

For a lot of people in Brownsville, awaiting a court date amounts to an ordinary passage of the teenage years. “Jail’s the most normal thing a lot of my kids in Brownsville do,” says Lieutenant Glassberg. “They see it as sleepaway camp. They see all their friends, they’re gonna have their own bed.” He tells the story of a teenager affiliated with Wave Gang who was recently sentenced to 17 days in jail for a felony—which the judge offered to drop to a misdemeanor in exchange for 16 hours of community service, picking up garbage at Betsy Head pool. “The kid chose jail,” Glassberg says. “How can I compete with that?”

In a similar vein, the implacable animosities that one would expect of a gang war were largely absent at Sahiah and Andre’s trial. It often seemed that the divide was not so much between Wave Gang and Hoodstarz—nor even the People and the accused—as between Brownsville’s residents and the outside world. “I’m not mad at the kids in the other gang, the kids they said Andre and his friends were fighting,” Andre’s mother, Sharon Moore, told me. “The enemies are the police. They don’t police, they harass. They hang out on the roof across the street. When there’s gunshots erupting, the officers is running away before you running.”

At the defense table, the lanky Sahiah had to stoop to whisper to Andre, who stands only five-three. She often wore a purple leopard-print cardigan, and Andre a pair of gray slacks and an argyle sweater. In the time since the crimes occurred, their features have become adultlike, as if their youthful mug shots were re-etched by a draftsman with a heavy hand. From time to time, they looked at the familiar faces in the audience and smiled, waved, or mouthed the punch lines to inside jokes, prompting their lawyers to exchange exasperated stares.

A critical piece of evidence was a rap song that investigators discovered in Andre’s cell phone. Titled “Wave Gang: Bring the Woonz Out” and recorded by two Wave members (“Woons” is Brownsville slang for homebodies), the song boasts about “how many Starz we shot” and belittles the Hoodstarz for not fighting back adequately after some members were killed: “All I see is a bunch of tweets, like ‘Why my bro, AC?’ and ‘Why they kill OCC?’ When my sons come, niggaz fade away like KC. They hide away. They don’t want to play.” A slow scroll of graphics that appeared at the end of a YouTube video for the song also issued a message to several Hoodstarz identified by their nicknames:

K. DOT

MURDA MALO

DEEIISS

BUDAA (FAGGOT ASS NAME)

YALL ALL DEAD MEN WALKING

#WOOOOOOOOOOO

GANG OR DON’T BANG

Meanwhile, Starajha Kelly, who had been friends with both Sahiah and Nathaniel Walcott, became a favorite of the audience, even though she provided detailed testimony of observing the defendant approach the boy with a gun and then seeing him die. This was because she testified that in the hours beforehand, she had been at a party and said that because she doesn’t drink, “I smoked six bags.” Most of the courtroom chuckled, and Starajha smiled triumphantly. “Not by myself,” she said. Starajha began anxiously but eventually collected herself, even as she was forced to admit on cross-examination that she had pleaded guilty for biting her mother and hurling a shopping cart at her from the top of some stairs, and had been arrested for striking a girl in the head before slamming it into a parked car.

Of the four eyewitnesses who saw Andre shoot Marlon Riley, only two could be located for testimony. One of them, tall, rubber-legged Devon Britt, kept his ski parka on throughout and said that when he and Andre encountered Marlon alone on Pitkin Avenue, Andre “asked the guy, ‘Was he chowing?’ ” That, Devon explained, meant “Are you Hoodstarz?” Then Andre “pulled the gun out and started shooting.”

Marlon’s mother and uncle jerked upright at this point in Devon’s recollection, then ran silently into the hallway. Through the doors, she could be heard shrieking. “I believe in an eye for an eye!” her brother bellowed.

Both defendants were found guilty of murder. Sahiah received a sentence of 20 years to life, while Andre’s additional charges resulted in a total of 50 to life. Marlon’s mother, who had banked vacation time from her housekeeping job at a Times Square hotel to attend the trial, said that even though it bothered her to have to see the family of her son’s murderer in court every day, she eventually began saying hello to Andre’s mother. “I don’t know how I’d feel in her shoes,” she added.

When the verdicts came in, Andre’s mother approached Marlon’s family and declared, “We both lost.” Marlon’s uncle, Patrick Scully, said he told her, “You still have your son to go visit. You can hug him. Who are we gonna hug? We gonna go hug a headstone?”

A handwritten sign in the waiting area at Rikers Island said “No blue, red, orange, green PUMAS. Only BLACK Pumas allowed. No brown, gray, yellow, lt. blue, purple. NO New Balance, Nike, Adidas. NO Converse All-Stars Hi-Tops.” This applied only to inmates and gifts visitors wanted to bring them. Andre, anyway, had on Patakis—black canvas prison slippers. “Sometimes people call them Obamas,” he said. “Because they’re shoes from the government.” He was also wearing an orange jumpsuit on which he’d written FREE ME and TRU, for True Religion Jeans, he explained.

He showed off the tattoo another inmate had given him using a hot staple as a needle and a melted-down chessman for ink. On his arm in cursive it read TAVI—for his sister, Octavia.

Andre not only maintains his innocence but says he was never in the Waves. “I was aware of Wave Gang, but I thought they were out in Queens,” he said. “Those kids are bragging on Facebook. Why would I be doing something that my mom’s on?” He brought up the Wave Gang All-In dance, however, which he said he was pretty good at.

“Step-step, wiggle-wiggle, bounce-bounce,” he said. “Me and a bunch of my friends came up with that version. By the time they put it on YouTube, I was in here.”

He felt he’d been railroaded. “The police went around locking up every guy in my building with a criminal history,” he said. He had a rap sheet, with a robbery arrest. And he thought the cops had it doubly in for him because of his father’s reputation. “When they arrested me, one of them said, ‘We know who your father is. We know the background you got.’ ”

Andre said he grew closer to his father after the murder charges came down. “Before, he was gone a lot, but he did what he could do,” he said. “We started talking more once I was at Rikers. We talk about my case, never about my dad’s affiliation with it”—how his father has also served time. “I never ask what he went away for. But I know he went through something like me. He told me to be strong.” Andre also took comfort in knowing there were plenty of his childhood friends right there with him in Rikers. “It helps to already know people, for real,” he said. “I see a lot of guys from Brownsville every day.”

Before his arrest, Andre had barely set foot beyond the limits of eastern Brooklyn. “I’ve been to Queens; I think I’ve been to New Jersey,” he said. “We was in PA once to visit some relatives.” All the same, Andre was eager, after his sentencing, to be transferred to a long-term prison upstate, in Dannemora. “It’s a lot nicer up top,” he said. “The food, more space, they got better TV.” It didn’t help that, for the past two weeks at Rikers, talking back to a warden had got him relegated to the Box, 23-hours-a-day solitary confinement in a cell no bigger than it sounds. “When you in the Box, you can talk to all the other guys in their own Box, up and down the hall—you just can’t see them,” Andre said. “We play Jeopardy! at night, yelling it out: ‘They invented flying.’ ‘Who was the Wright brothers?’ ‘Martin Luther King was shot this year.’ ‘What is 1968?’ ”

An unexpected aspect of life in jail is that whatever fundamental differences the Wave Gang and Hoodstarz had with one another—differences they somehow considered worth risking their lives and those of others over—pretty quickly lost significance when they were away from home. Devon Griffith, another boy from Brownsville who recently served six months in Rikers for robbery, told me that kids from the two gangs stopped fighting once they were all locked up together. One night in the Box, a chorus of boys called out “Cho” from their cells to let a Wave Gang leader who was there know that in his immediate surroundings he was outnumbered. “He yelled back to them ‘All right, all right,’ and stopped telling people he was Wave Gang. And then the Hoodstarz stopped hassling him and the beef kinda ended in Rikers,” Andre said. “Now they cool.”

I asked what he missed about life outside. He said he’d had a girlfriend in Brownsville and they were still in touch. “They put me away before senior year—I was gonna finish high school,” he said.

My parents were some of the first people to live at Langston Hughes,” Andre’s mother, Sharon Moore, said. “This was a very hopeful place for large families.” She was sitting in her living room, high above Sutter Avenue. The buildings and grounds are in ruin: trash throughout the courtyard, cracked windows in the lobby, graffiti and mismatched repair work in the hallways, the smell of urine in the elevator. But Sharon’s home was tidy. On the wall behind a tan velour sofa was a montage of her children’s school photographs. Sharon wore librarian glasses and fuzzy slippers with purple trim. Except for Andre and a daughter who joined the military, all her children live with her. She said she’d been working as a caseworker at the Family Services Network of New York until she got laid off in October. She appreciated that when that happened, her rent automatically dropped from $708 a month to $525.

She said that Andre’s father, who had been a childhood friend of her brothers, was taking Andre’s sentence hard, “because he knows the experience that Andre has ahead of him.” And she didn’t believe her son had shot anybody. “If Andre and these kids were in gangs, then how come there’s still so many shootings even after they got sent away?” she said. Andre’s brother Quaron, also indicted in the case, pleaded guilty to a misdemeanor and served 17 months in jail. Last fall, he was shot in the leg, “right out there in front of our building,” Sharon said, pointing to the window. “That was very scary. He doesn’t know who did it, but it didn’t have anything to do with gangs.”

Sharon turned on the TV and called up the prerecorded news to show me that in just the previous week, there had been two more outbreaks of violence in Brownsville. Seven teenagers altogether had been shot—one fatally—and a girl was pistol-whipped. “There’s a war going on,” she said. “People say it’s the norm now, but how do you move? Where am I going to go?”

Her youngest, Gregory, came home from school at lunchtime and began watching The Fresh Prince of Bel-Air on a 40-inch flat-screen. An hour or so later, Quaron emerged from a bedroom in flannel pajama pants and handed Sharon her cell phone. Andre was calling from Rikers. “Hello, Mr. 22-years-old-today,” Sharon cooed into the phone. She began to sing: “Happy birthday to you. Happy birthday to you. Happy birthday, dear Andre. Happy birthday to you.”

Sharon blamed Andre’s court-appointed attorney for not “reinvestigating” the killings. And Sahiah’s father, James Davis, a chef who lives in the high-rise next door from Sharon’s, also felt let down—by her representation and by law enforcement. Officers had testified that they’d been familiar with the kid for years. “They’d been watching them and doing what? So they’d been saying since they were 12 years old, they wrote them off?”

James added that Sahiah, now at Bedford Hills, a women’s prison in Westchester, has spent the past three years working to earn a high-school GED. “Sahiah is my princess, my angel, my queen,” he said. “When she was growing up, I tried to be prepared for everything—what if she falls and hurts herself, what if she had a boyfriend and gets pregnant when she’s 16. But nothing come along made me think I had to be prepared for her getting put away for murder.”

At Sahiah’s sentencing hearing, LaToya Walcott, AC’s sister, said she’d turned to drinking and drugs for a while after he was killed. “It was always the two of us and then everyone else,” she said. “When my grandmother told me that my brother was shot, my brain tried to reject what my heart knew was true.” Before long, she added, “my ambition died. I went to school and did nothing … I figured, Why try to make something of myself when someone’s going to take my life too?”

Some of the kids who managed to cop pleas in the aftermath of Operation Tidal Wave are back home in Brownsville now. A few weeks ago, I visited with two, Tylek Hayden and Devin Yard, at Tylek’s grandmother’s apartment on Mother Gaston Boulevard. Tylek is enrolled in job-training programs but both say their futures are hitched to the rap group they formed with a third friend. I’d sought them out, in fact, because it was their song—making fun of the Hoodstarz for absorbing their losses without sufficient retaliation—that was played to the jury at Andre and Sahiah’s trial.

“That’s just hip-hop,” Ty explained. “We came up with the name Wave Gang, but it wasn’t even a gang. We’re a rap group. And then other kids started saying they’re Wave Gang, maybe, but we can’t be responsible for what they do.”

Devin said that the war with Hoodstarz was a “police-made-up thing,” and that the threatening lyrics were “just a joke.”

“Matter of fact, we good friends with a lot of those guys and I hung out with them all the time in Rikers,” Devin went on. “Matter of fact, some of those guys rap and just recently we were talking we said, ‘Maybe we should revive the war and start writing more songs about each other, just for the fame.’ ”

Now Ty and Devin are calling their act D.O.D., which stands for Definition of Dreams. They recently recorded a single, “Make It Out,” about trying to leave Brownsville behind—which, they concede, is an essential but elusive goal. A few weeks ago, they rented a bunch of cars from Enterprise to use in a music video—including a BMW and a Wrangler. The next day, two of their friends, who were parked in the BMW in front of the Seth Low Projects, got shot in broad daylight. One died in the hospital. “It’s Iraq here, still,” Ty said.

Around 5 p.m., the local news came on Ty’s grandmother’s TV. The boys watched as clips played silently of Maya Angelou, whose death had been reported earlier in the day.

“She wrote books and some crazy poetry,” Ty said. “She crazy famous.”

“All these legends, why they always seem to be passing in their own house?” Devin said. “Somebody that knows them always finds them.”

“Man, that would be the way to go,” Ty said.

Devin smiled admiringly. “Dying from old age,” he said, shaking his head.