Netty Nance is 24 but can seem much younger. Her hair dangles in long, wild braids over enormous gold medallion earrings. On her hand, tattooed in thick script, is her daughter’s name, Samani. “She’s my miracle baby,” Netty tells me. “If it wasn’t for me getting pregnant, this never would have come out.” She is referring to the discovery she made, one so dramatic it upended her life and the lives of the people closest to her. She’s spent much of the past year both embracing what she learned and trying to wish it away.

Seven years ago, Netty was a senior in high school living in a poor section of Bridgeport, Connecticut, and got pregnant. By the fall, she couldn’t hide it anymore, and didn’t want to. She was excited. Her cousin Brittany was pregnant, too, and now they could be mothers together. But she needed prenatal care, and to get free services from the state, she had to have a birth certificate. Her father, Robert Nance, was a sometime drug dealer who only saw Netty now and then. It was her mother, Ann Pettway, who raised and supported her. But when Netty asked her mother how to get the documents, Ann brushed her off. “She said she was going to handle it,” Netty says.

Netty got tired of waiting. She searched through Ann’s things, found a document with her name and birth date on it, and brought it to the Bureau of Vital Statistics in New Haven. The clerk couldn’t find her records. Netty was furious. But when she pressed, a supervisor all but accused her of trying to assume a false identity. She told Netty that if she kept trying to pass off what she had as I.D., she might be arrested. Netty exploded. “Keep it,” she said, and left the office.

When Netty got home, she told her mother what had happened. Ann shook her head. “I told you I was going to handle everything,” she said.

Before long, the Department of Children and Families called the house for Netty’s mother. Netty wasn’t privy to what they talked about. They might have just asked about the paperwork, or they might have mentioned that without proper I.D., Netty would need to enter their system, becoming a ward of the state. Whatever they spoke about, Ann called Netty several days later, before leaving work, and told her she wanted to talk to her when she came home.

When Ann came through the door that night, she went straight upstairs to Netty’s room, sat down on the bed, and started weeping. In her whole life, Netty had never seen her mother shed a tear. “What are you crying for?” Netty asked.

“Your mom left you,” Ann Pettway told her, “and she never came back.”

It was a full seven years before Netty learned the rest of her story. Her real name was Carlina White. She had been abducted as a newborn baby, nineteen days after her birth, from Harlem Hospital and never seen again. And Ann Pettway was not only not Netty’s real mother—according to the police, she was her kidnapper.

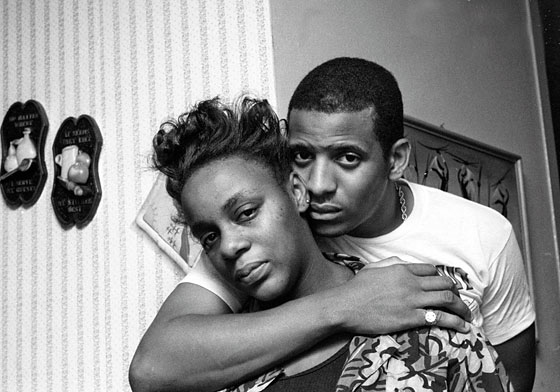

Carl Tyson has large, bright eyes and caramel-colored skin. The resemblance to Netty is unmistakable. We’re having lunch at a diner near his home in Queens. The whole time Netty was missing, he tells me, he never lost faith. “I always felt that my daughter was going to come back. I didn’t know when, but I knew. Joy was the same way. She always had that feeling.”

Joy White and Carl Tyson had been the first couple among their friends to have a baby. It was 1987. Carl was 22, driving a truck and working nights in a parking garage. Joy was 16 and still in high school. They had grown up in Harlem housing projects across town from one another, and were together a year when Joy called Carl at work one day, saying she felt sick. The pregnancy wasn’t planned, but the couple stayed together. Carlina Renae White was born at Harlem Hospital on the afternoon of July 15, a healthy eight pounds.

Joy and her mother took care of the baby at her place; Carl stopped by at night after work. But on August 4, when Carlina was 19 days old, she developed a high fever. Joy called Carl, and they took the baby back to Harlem Hospital. On their way in, Carl remembers being directed by a heavyset black woman in her twenties wearing a nurse’s uniform. Carl didn’t think much about it at the time, but he’d glanced around for her name tag and couldn’t find one.

The doctor wanted Carlina to spend the night, and Carl searched for a phone to call their mothers. When he looked back down the hall, he saw the woman in the nurse’s uniform again, talking with Joy. “The baby don’t cry for you—you cry for the baby,” the nurse told Joy. She seemed to be saying that the baby was fine; it was Joy who needed help. It struck Carl as a strange way to console a young mother.

The couple decided that Joy would spend the night at the hospital, but first Joy wanted to get some things. They left together at about 12:30 a.m., about the same time as the nurses’ shift change. Carl dropped off Joy at her mother’s apartment, went home, and fell asleep.

Carl’s phone rang a few hours later, at about 6 a.m. It was the police, calling from Joy’s mother’s apartment. A detective said Carlina was missing. Joy seized the phone, screaming—“Please get here!” When Carl got to Joy’s mother’s building, police cars were parked outside and detectives crowded the hallways.

Inside, Joy was in pieces, sobbing. Soon Carl was, too. The hospital had discovered that Carlina was gone at 3:40 a.m. Whoever took her had unhooked her IV tubes and left the floor without being seen. The hospital claimed the baby had been checked every five minutes. The police believed the kidnapper must have been studying that pattern and had taken Carlina at just the right interval. They suspected a heavyset woman others had seen around the hospital for the last few months. She wasn’t a nurse, the hospital said, but had passed as one, even convincing other nurses that she belonged.

Joy thought about that strange remark outside Carlina’s hospital room—The baby don’t cry for you, you cry for the baby. “She was trying to get rid of me,” Joy would later say, “so she could take my baby away from me.”

For a time, police thought they had a suspect, a 31-year-old woman named Lucy Brockington. She was wanted for car theft and fit the relevant description. Detectives tracked her down in Baltimore, questioned her, and decided she had an alibi. After that, there was nothing—no sign of the woman or the baby. Carlina White was gone.

Joy left school for a year, began taking anti-anxiety medication, and went to therapy several times a week. Carl says he “would hardly eat. I was angry with everyone. My temper was short.” He would sometimes ask himself why Joy didn’t just stay at the hospital. Or “Why didn’t I stay?” His very presence reminded Joy of Carlina, and hers did the same to him. “It was so much to handle,” Carl says. They broke up about a year after Carlina vanished.

Ann Pettway grew up in the East End of Bridgeport. She attended Warren Harding High School, where Netty would eventually also go. Ann was popular and fun. “Everybody said she used to be bad,” says Netty. “She was out there with those Speedo shorts on, tube tops.” As a teen, Ann served a month in jail for a larceny arrest in a neighboring town; later, she would be caught in a few minor theft and forgery schemes, along with one pot bust. But “she wasn’t a hell-raiser,” says David Daniels, a Bridgeport police officer who knew the family.

In 1987, Ann told friends and relatives she was pregnant. Everyone assumed the father was the boyfriend she’d been seen with on and off, Robert Nance. One of Ann’s younger sisters, Cassandra Johnson, would later tell the National Center for Missing & Exploited Children that she first saw a baby with Ann when Ann arrived with her one day on a Metro-North train. A cousin of Ann’s says Ann left town for a period of time. No one Ann knew seems to have been with her when the baby was born. People assumed she’d gone away to have the baby and then came back.

In January, when the story of the alleged kidnapping broke, Netty told the New York Post that Ann was “an addict,” often in a drug haze. “There were always drugs lying around,” she’d said. “I used to see weapons.” When Ann would come down from a high, Netty said, she’d run out of the house before Ann became “a monster.” Once, she said, Ann hit her in the face with a shoe so hard it left a mark. But now, as we’re speaking, Netty tries to recant it all. She says she is more forgiving—that everything that happened in her childhood was standard issue for where she grew up. “Growing up in an urban family, you were going to get beat, no matter what it was.” Netty takes pains not to call it abuse. “That’s what people want to hear, the sob story,” she says. “But I wasn’t abused. Everything that an average person would have, I had.” Ann was responsible, she now says, but remote—never cruel, but not exactly tender, either. “I’m not going to say she was the best mom ever, but she did what she had to do to make me who I am. She was strict, but she was cool. All my friends used to say she was a cool mom.”

Ann supported Netty by working as a janitor at a local civic center in Bridgeport. Until high school, she sent Netty to live during the week with her own mother, Mary, who lived in a slightly better part of town, so Netty could go to better schools. Her elementary-school principal remembers Netty as her favorite student—“so pretty and so vivacious.” When Netty was about 10, Ann had a baby, a boy named Trevon, and by then Netty was spending much of her time with her cousins and aunts. She was especially close to Ann’s sister Cassandra—“my bestie,” Netty calls her. She spent her time studying new dance steps; writing rap lyrics; and dreaming about modeling or making movies. “Dancer, rapper, model, whatever, I said, ‘I’m going to be famous.’ ”

At least one cousin has said that relatives would speculate behind Ann’s and Netty’s back about the child’s looks. Ann was dark-skinned, and Netty was light. Netty remembers gazing at pictures of Ann to see if the two of them looked the least bit alike. “Everybody called me Little Ann,” she says. “But I didn’t see a resemblance.”

The night Ann told Netty she wasn’t her mother, “my whole stomach just turned up,” she says, “like, ‘What are you saying? What the hell are you talking about? This is not my family? That’s not my grandmother downstairs?’ ” Netty asked who her mother was and where she came from. Had Ann met the woman, or was Netty left on the doorstep? Why didn’t Ann take Netty to the police or a hospital? Why didn’t she ever tell Netty?

With each question, Ann repeated the same answer. She left you and never came back. There was nothing more to it, she insisted. “No names, no nothing.” For weeks, Netty kept asking, but “it would never go nowhere. Even when a year passed by, I was like, ‘You don’t remember nothing?’ ‘No.’ ” Netty and Ann stopped discussing the matter with each other and told no one else about it. But Netty was still curious. She had trouble believing that she had just fallen into her mother’s lap. Her suspicions grew, and she and Ann became more distant. Her relatives had said that Ann was pregnant in the summer of 1987. Was she really pregnant? Did she miscarry? Just before a stranger handed her a baby?

Netty asked her Department of Children and Families caseworker if her DNA could be cross-referenced with some DNA database of missing children. “That’s TV stuff,” the caseworker said. Robert Nance, who was in jail at the time on a rape charge, called Netty after a DCF investigator visited him. Netty asked what he knew about her mother. He and Ann weren’t together by the time Netty was born, he said. If Netty really wasn’t his and Ann’s, he said, he wouldn’t have known.

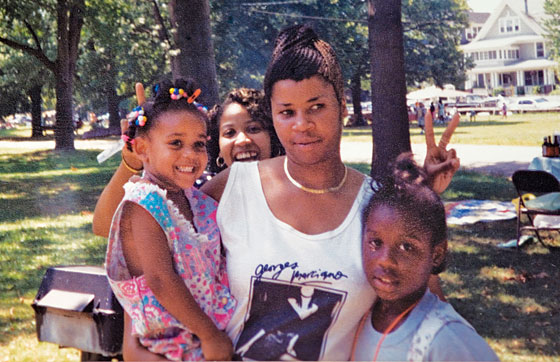

Samani was born in 2005. Netty got her high-school diploma, took a job as a motel-desk clerk, and, when Samani turned 1, moved to her own place; then, two years ago, she moved to Atlanta, where her aunt Cassandra had moved a few years earlier. She found work in a hair salon, tried a little modeling, and still harbored dreams of being a rapper. Ann sent cards and gifts to Samani. Eventually, Netty told Cassandra her secret, and Cassandra encouraged her to keep searching for her birth mother. Late at night, Netty would find herself trolling the Internet for stories of missing children. “Missing child 1987,” she’d type, sometimes adding “Connecticut” or “New Haven.” She never turned up anything. “I’d look at the picture, but it wouldn’t be a child that’s my color. There would be no resemblance.”

Then, last December, Netty went to the website for the National Center for Missing & Exploited Children. The site showed pictures of hundreds of kids from all over the country. For the first time, it dawned on Netty that she could have come from anywhere, not just near Bridgeport. She combed through the photo archive. She saw a picture of a baby girl—a newborn who was just 19 days old when she vanished on August 4, 1987.

Netty dragged the photo to her desktop and saved it. The baby’s face reminded her of Samani. And Samani, everyone told Netty, looked just like her.

Three days before Christmas last year, Netty called the National Center for Missing & Exploited Children’s hotline. “I feel like I don’t know who I am,” she said. She didn’t mention the photo of the baby. At one point she was so overwhelmed she put Cassandra on the phone. “She was agitated,” says the center’s president, Ernie Allen. “She talked about how she’d been trying to get information about her identity for five years. My sense was this was almost a call of desperation.” In that first call, Allen says, Netty also revealed her suspicions about Ann. “She said she believed the woman known to her as her mother abducted her near the time of her birth.”

Netty had trouble with even basic questions. “I guess I’m African-American,” she said—but how could she know for sure? It was Cassandra who reminded Netty of a birthmark on her right arm, a detail the center was able to cross-reference with its records of missing children. “We ultimately narrowed the search to two cases,” Allen says, “and one of those was Carlina White.” The forensic unit compared Netty’s baby pictures with the photo of Carlina at 19 days old, Allen says, and they appeared to be a match. “There was nothing to suggest this was not Carlina.” Tellingly, the birthmark, too, appeared to be in the same place.

Just after Christmas, the center reached out to Joy and Carl. Joy was at work when the center e-mailed her photos of Netty. She screamed and cried. “Both of them were adamant, saying this was their daughter,” Allen says. The center contacted the NYPD’s missing-persons unit. The police took DNA swabs from Carl and Joy on January 6 and went to Georgia for samples from Netty shortly after that. Even before the results were in, Netty decided to call Joy.

Joy was on her way home from work when the phone rang. When she called Netty back, “she had me on speakerphone, with all the aunts. One of the aunts was like, ‘Come home!’ I was happy as hell,” Netty says. “But in the back of my mind, I’m like, What if this is not it?”

Then Joy mentioned the birthmark. Netty was overwhelmed. “I said, Wow. This is real now.”

Netty asked Joy about her father, and Joy told her about Carl. “I called him, and I talked to him for a while,” Netty says. “But me talking to him was more awkward. The mom had that mother instinct. The dad is like I was talking to a stranger.” She was still elated by the contact.

For two weeks, Joy and Carl were on the phone almost constantly with Netty. “We’re talking, and all of a sudden she’s calling me ‘Dad,’ ” Carl says. “And I’m sitting here saying to myself, I can’t believe it. This is my daughter. That’s my firstborn. And Joy would be trying to call, too, and so she would say, ‘Dad, Mom’s on the phone.’ And I was like, This girl is calling us Mom and Dad!”

On Saturday, January 15, Joy paid to fly Netty and Samani to New York to visit. Netty had wanted them to come to her, and Carl had the time—he was home on disability after a truck accident in October—but Joy was having trouble taking time off work. As soon as Netty landed, there was a glitch. Carl had agreed to pay for a rental car but couldn’t be there to meet the flight. He says he had a doctor’s appointment for his work injury; Netty says he was traveling to a casino with some friends. When Netty tried to rent the car, the company forbade it. “You have to be 25,” she says. She was starting to get uneasy about the meeting.

When Joy and her sister Lisa White-Heatley came to pick her up, she began to feel better. “They were just staring at me, going, ‘Oh my God! You look like your dad. You look like your mom, but you got your dad’s eyes!’ ” Joy started to cry.

They took a taxi to Joy’s apartment, where Joy made curried chicken, macaroni and cheese, lasagne, and oxtail. All of Joy’s extended family were there. Netty met her sister and brother (Sheena, 18, and Sydney, 21), aunts, cousins, and a grandmother: Joy’s mother, Elizabeth.“She just fits right in,” Elizabeth said later. “She brought her beautiful daughter. It was magic.” For the time being, Netty and Joy steered clear of talking about Ann Pettway and Netty’s childhood. Instead, they searched for traits they had in common and made little lists of mannerisms and habits they shared. They cooked together, watched Samani play with a new set of cousins and aunts and uncles. “It felt like this is where I belonged,” Netty says.

The next morning, Carl went to Joy’s house to meet Netty. “I’m waiting for her to come downstairs, I’m sitting there like a little kid waiting to get his new toy. I’m shaking. Suddenly this girl comes out of the building. I get up out the car, I go up to her. Tears started coming out my eyes. She said, ‘Dad, don’t start crying, don’t start.’ ” When Netty got in Carl’s car, he just kept staring at her. “She said, ‘Do I have something on my face or something?’ I said, ‘No, girl, you don’t understand what me and your mother went through. Just to see you standing here is a blessing.’ ”

But Netty’s unease returned. She still wanted to rent a car, but the outlet she and Carl went to wouldn’t give her one, and Carl wouldn’t rent one on her behalf. It wasn’t legal, and he was afraid of the repercussions if something happened. “She got upset about that,” Carl says. Netty asked Carl to drive her back to Joy’s. He went to an ATM and took out some cash for her to get her hair done. That also rubbed her the wrong way. “Money doesn’t buy me,” Netty says.

Carl told Netty he just wanted to spend some time with her. “She said, ‘I’m 23. What you want to do?’ And I said, ‘Whatever you want.’ She said, ‘Well, I want to get my hair done. What are you going to do?’ And I said, ‘I’ll sit next to you. Twenty-three years I haven’t seen you. I don’t care if you want to sit in the park!’ So we’re sitting there, and she was like, ‘You know, it feels strange having a man here.’ And I said, ‘I ain’t a man, I’m your dad.’ And she said, ‘Yeah, well, the papers haven’t come back yet.’ ”

Joy tried to smooth things over. “Maybe she just feels that way because she’s just meeting us for the first time,” Carl says Joy told him. He tried his best to see Netty in the days that followed, but she spent most of her time with Joy. It wasn’t all bad: Above all, he was just happy she was alive. Still, though he didn’t want to admit it, Carl was getting angry. “I don’t want to say nothing about her. But her attitude. I’ll be honest with you—if that young lady wasn’t my daughter, she would have been out of my car a long time ago.”

By Tuesday, Netty was starting to feel homesick for Atlanta. At the airport, just before she boarded the plane, she was approached by someone she’d never seen before. “A man came up to me. He was standing next to me and said, ‘Are you Nejdra Nance?’ I said, ‘Yeah.’ He said a detective told him to tell me to call him. And I’m like, ‘Why?’ And he said, ‘We got the DNA back. It came back positive.’ ” The NYPD had been trying to reach Netty, Joy, and Carl. They were surprised to find out they were all in New York.

After getting word at the airport, Netty and Samani went ahead and boarded the plane back to Atlanta. Netty didn’t even call Carl and Joy. “If that was me, and I find out right then and there the DNA came back, and that’s my parents,” says Carl, “I wouldn’t have got on the plane.”

The next day, Carl and Joy called Netty. The news had broken. By anyone’s estimation, no child in American history had ever been missing longer before being reunited with her parents (the only case that comes close is that of Jaycee Lee Dugard, the young girl abducted and held prisoner in California for eighteen years). This was a big story. The Post wanted to fly Netty back to New York and put her up, with Carl and Joy, at the Essex House. Netty agreed to come, this time without Samani, who stayed back with Cassandra. When Netty got to the hotel, “the whole media was outside. They were booking rooms on my same floor. I couldn’t leave the room without someone seeing me. They had to lead me out the kitchen to leave the hotel.”

“You say you don’t know us? Fine. But how are you going to get to know us?”

Joy was unequivocally happy. “I always dreamed this,” she told a reporter. “Now I can sleep!” She told another, “She’s just like me. We like the same colors. We like our houses to be clean. We can’t go to sleep without the dishes being washed.”

Netty tried to be happy, too. “I feel complete,” she said. But the attention made her feel fake. “We were in front of this camera. They were telling us to kiss on the cheeks and hold hands. This ain’t even me, you know what I’m saying? We didn’t even get to do this on our own yet, so why are we doing it for these people?”

Netty found herself thinking about Ann. It wasn’t just that Ann had lied to her. She was an accused kidnapper now. The FBI was looking for her, and she was facing a federal prison sentence of twenty years to life. Ann had been living in Raleigh, North Carolina, for a few years, apparently working recently as a kitchen prep cook. News reports cited what Netty had said about Ann to paint her as abusive. When the Post reached Ann, she’d vowed to make things right. “I’m coming, I’m coming, I’m coming back to straighten this all out,” she said. “I raised her, and I was a good mom.” Then she left the state and disappeared.

When the subject of Ann came up at the Essex House, Netty grew stern, refusing to look at the police sketch from 1987 or even mention Ann by name. “When I look at [Joy], I can see me. With that other lady, I would always be searching for stuff we had in common, but I had nothing in common with her.”

“I want her to suffer,” Joy said about Ann. “I want her to do some time, like I suffered for 23 years.”

The next morning, Netty said she wanted to go home to Atlanta. Carl and Joy couldn’t believe it. “But I’m like, ‘I need to get back to my kid.’ I don’t want all the attention. I just want peace of mind.”

Back in Georgia, Netty stopped calling her newly discovered parents as often as she had been. The media kept coming after her. Netty became so anxious, she says, that when anyone would approach her she’d start to shake. She checked in to a hotel in Georgia to avoid her house.

But the calls didn’t stop. A few years earlier, still in the midst of searching for her real mother, Netty had written Oprah Winfrey a letter about her situation and never heard back. Now an Oprah producer was on the phone, reading her letter back to her. “It was just like, ‘Wow, you all got it and you’re just getting back to me now?’ ”

Joy wanted to do the show. Carl was fine with it. Netty said yes at first, then changed her mind. Although Oprah would have been an uncomplicated celebration for Joy and Carl, Netty would be the one having to talk for an hour about her life and childhood and what sort of mother Ann had been. The weight of what was happening to Ann, and Netty’s role in that, had begun to sink in. Netty was also worried about Trevon, her little brother. Netty had a new family now, but he still only had Ann. What would happen to him if Ann went to jail?

“I told my mom, ‘I can’t do it,’ ” Netty says. “And she was like, ‘Why?’ I knew that she was upset because everybody looks up to Oprah. I did too. Oprah’s my idol. At the same time, I didn’t want to talk about the story anymore. I just needed some time to myself.”

Netty believes that nothing was the same with Joy and Carl after that. Joy and Carl were upset that there was no plan in place to see her. On January 23, Netty watched on TV as Ann arranged her surrender to the FBI in Connecticut.

From the start, Ann’s lawyer, Robert Baum, seemed to campaign for a plea deal—hinting that he’d fight the case if it went to trial, and that Ann wasn’t the monster she was made out to be in the press. “She knows she was a good mother; she knows she gave her everything she could give her, and that Carlina was happy. That she feels good about. But she does feel badly and guilty about raising her and keeping the secret about how she got her. But that’s still an open question: how she got her.”

Based on statements Ann made to the FBI after her surrender, prosecutors say Ann miscarried sometime the summer Carlina was born and became desperate to become a mother. Baum doesn’t necessarily dispute this, but he says the evidence that Ann kidnapped the baby is far from conclusive. It’s possible, he says, that someone else took Carlina, although he has yet to say who did or how Ann wound up with her. In court on January 24, Baum suggested that Netty could be a good witness for the defense. “The person you’ve identified as the victim is in fact with Ms. Pettway’s family,” he said. “They believe she has been and may continue to be for many years a good mother.” Carl went on television saying he didn’t think Ann was really sorry. But it was lost on neither Carl nor Joy that Netty was no longer joining those condemning Ann. “I know she wants to unite with us,” Carl said on the Today show. “But she has had this other family all these years.”

On February 8, Carl appeared on The Early Show and claimed that everything was still all right with Carlina. “I just got to move forward step-by-step,” he said. “She’s 23, so it’s like kind of hard to talk to a grown-up that you haven’t seen since she was a baby. So it’s kind of a little tough. But I’m trying.” Joy, meanwhile, went on Today and accused Netty of actively distancing herself from both her and Carl. “I was on such a high when I first reunited with my daughter,” Joy said. “I was floating on air. I was so happy, and that moment was so great.” Now, she said, “I’m disappointed. This was a miracle that happened. It’s breathtaking. And I just wanted to get that out there, that we found our daughter and that we’re happy. We’re reunited, and I wanted to share that with the world. And it really hurts me that it’s—it’s about money.”

Shortly after Netty had first come to New York to meet Joy and Carl, reports had surfaced of a trust fund. In 1988, the year after Carlina went missing, Carl and Joy had sued the city, which ran Harlem Hospital, for $100 million. In 1992 they reached a settlement of $750,000. Each parent’s share was eventually reduced to $162,643.28. Carl and Joy agreed to put half of each of their shares, or a total of roughly $162,000, in a trust fund for Carlina, should she return before her 21st birthday. When the trust was liquidated, in 2008, Carl and Joy each collected what they’d put in. “I have two other kids,” Joy told Today. “And I had to take care of myself. And I had to live.” “Some parents probably wouldn’t put any money away,” says Carl, who says he lost much of the money in a divorce. “Me and Joy, we did 21 years.”

Netty, Joy seemed to be saying, was less interested in reuniting with her parents if the trust fund was gone. But Joy also told the Today show that she realized Netty was attached to Ann and Ann’s relatives. “I do have to understand that that is her family, you know. She was brought up by them. I’m her mom, and she is—you know, she’s just like so—it’s just so hard to explain. She’s with that family, and that’s all she knows.” Joy also said she very much wanted Netty in her life. “I’m her mother, and it hurts not to have a relationship with her. It really hurts. And I want my daughter back, I want her here, and I want her to spend time with me and the family, and I want her to get to know me. It’s like we’re two strangers. We don’t know each other.”

Netty didn’t comment on what Joy said at the time. But she now says she was furious about it. “The people who knew me when I was going through this and knew how passionate I was to find out who my parents were, they know this stuff is not based upon cash,” she says. At the same time, Netty acknowledges she asked Joy about the trust. She says that a lawyer who was advising her at the time suggested she ask about it. She says she didn’t feel comfortable bringing it up in person, so she decided to text Joy about it. “I asked her, and she said something about how whatever people were saying [about Joy and Carl still having a lucrative trust fund] was not true. So I was like, ‘Okay.’ But I guess they took my ‘Okay’ as, like, you know, ‘Whatever.’ ” Joy’s comments left Netty feeling betrayed—that she made them at all, and that she made them publicly and not just to her. “How dare you go on TV and say something like that?” Netty says she asked Joy on the phone after the show. “I never asked y’all for anything.”

In May, Robert Baum announced that Carlina White would “be supportive in every way” of Ann Pettway in her kidnapping case—even testifying on her behalf if needed. By July, Netty had cut off all contact with Joy and Carl.

Ann Pettway has spent the last nine months in a federal detention center in Manhattan. While an FBI agent says the statements Ann made about miscarrying and desperately wanting a baby essentially amount to a confession, Baum intends to argue that there is no physical evidence placing Ann at the hospital that night. The judge had hoped to get the trial started this fall, but that now seems unlikely. Baum wants a chance to investigate other possible suspects and leads. He just received the complete case file from prosecutors, and was recently given time to track down Lucy Brockington. “Several witnesses at the hospital at the time picked out Lucy Brockington’s photo as the person in the nurse’s uniform they believed was responsible for the crime,” Baum says. “One of those witnesses who picked her out at the time was Joy White.” Brockington matches the police description of the woman who posed as a nurse: black, between 25 and 30 years of age, about five foot eight and 180 to 190 pounds. Of course, so does Ann Pettway.

When I ask Netty if she would ever want to visit Ann in jail, she makes a face. “I don’t really know,” she says. “I don’t like jails, and I don’t like hospitals. That’s not what I do, and I’m not going to get out of my comfort zone.” Would she ever communicate with Ann again? “Yeah,” she says. “But it’s going to take a little while for that to just—when I’m ready to, I know that I will. Just not at this moment.”

The hard part, she says, is talking about Ann with Samani. “She’s very close with my daughter. She did more stuff with her than I think she did with me. She took her trick-or-treating. Christmas, Halloween, school. She provided like a grandmother’s supposed to. My daughter still talks about her now. But when it comes to her being incarcerated, I can’t say that to her yet. She doesn’t know the story. I just say she’s on vacation.”

Back in Atlanta, at her lawyer’s office, Netty tells me she has switched her cell number several times, scrapped her Facebook and Twitter accounts, and stopped returning e-mails from practically everyone. Even the therapist she’d started seeing had no way to reach her for a time. She says she spent the summer with Samani, working some in a hair salon and making vague plans to study photography and filmmaking. “I have to get clarity on who I am. I have bills to pay. I have to teach my daughter. I’m trying to build my own career. I can’t just sit here and dwell.”

A friend of Joy’s says she is desperately sad and terrified of commenting publicly again for fear of driving Netty further away. Carl, meanwhile, is enraged. “She says she’s got to live her life? Okay,” he tells me. “But you’re not spending any time with your family. None at all. You say you don’t know us? Fine. We don’t know you. But how are you going to get to know us? I’m frustrated. I’m tired of my kids asking when they’re going to see their sister, can they call her? I tell them I don’t have the number, and they say, ‘What do you mean?’ I know one thing. If I were her, from January to now I would have at least seen us once.”

Netty isn’t blind to the fact that she has caused Carl and Joy pain. I ask her what she’d say if Joy called her now. “She can’t call me,” Netty says. But a moment later, she corrects herself. “I did what I did because I felt like when I’m ready to dip back in, it’s going to be on a different note. The approach has to be better than it was the first time. It was just too much commotion.”

A few weeks later, Netty tells me that she called both her parents. Her conversation with Carl was brief. But the call with Joy lasted three hours. “It’s been on my conscience,” she says, explaining that she needed “just to have the right words and be able to have the understanding. And I got what I wanted, from my mom at least.” The trust-fund issue, she now says, was “just a misunderstanding.” What really put her and Joy at odds was Ann Pettway. “I know they both want justice,” Netty says of Joy and Carl. “I would feel the same way if someone did that to my child. But at the same time, I have unconditional feelings for her.” She means Ann, though she still won’t mention her by name. “I’m willing to forgive her. And I still have love for her.”

Netty says she is happy she knows the truth now. “There was a part of me that wasn’t even there, and now I feel whole. Even in the beginning of the year, with all the drama and stuff, I was kind of cloudy. But now I know who I am. That’s the main thing—just to find out where you come from and who you are.”

So, who is she? Is she going to remain Nejdra Nance?

“No, she says. “I’ve been trying to get my paperwork together. When I get my I.D. and everything, it will say Carlina White.”

But there’s a caveat. “When someone asks me what my name is,” she says, “I say Netty. I don’t tell them my name is Nejdra, and I don’t tell them Carlina. Netty’s not what the Pettway family gave me or what the White family gave me. It’s what I gave myself.”