Twelve hours into 2007, Brownsville registered the city’s first murder of the year—a 26-year-old man shot in the back while walking to the store. This year, the neighborhood held the same unfortunate distinction: Just after 2 a.m. on New Year’s Day, another 26-year-old—shot in the chest in front of a Brownsville housing project—became the city’s first murder victim of 2008.

The intervening year was chaotic and violent in this pocket of Brooklyn. As the citywide murder rate was dropping to its lowest level in decades, murder was on the rise in four neighborhoods here: Brownsville, East New York, Bushwick, and Bedford-Stuyvesant. Together, these adjacent police precincts in northeastern Brooklyn accounted for nearly a fifth of the city’s murders and almost half the borough’s. The police scanner rang out with these locales all year: a teen shot in the head in Bushwick Houses; two teens and a 21-year-old gunned down on Brownsville’s Lott Avenue, the site of at least three shootings; a 16-year-old pounded with two slugs to the chest in Bed-Stuy’s Tompkins Houses. On it went.

Of course, like the rest of the city, northeast Brooklyn is still phenomenally safer than it once was. Back in the early nineties, people in these neighborhoods got killed at two and three times last year’s rate. “We had 765 murders in 1990; this morning it was 207,” said Brooklyn District Attorney Charles Hynes, a few days before Brooklyn’s final 2007 tally reached 212. Still, the murder rate here has been trending upward—with occasional fluctuations—since 2001. What is making this part of Brooklyn so resistant to the positive developments in the rest of the city? In 2003, Hynes commissioned a study to try to answer this question. “I woke up one day and said, ‘I can’t figure this out. We see the numbers coming down, but we see certain areas of definable levels of violence, particularly homicidal violence, and maybe we should go to academe [for answers].’ ”

What the academics found was a new kind of gang. The massive, corporate-style drug organizations of the eighties and early nineties are long gone from the streets of Brooklyn—driven out during the boom years by aggressive policing and an improved economic outlook. What they left in their wake is a wildly fractured drug market populated by an amorphous and crowded field of close-knit, hard-to-identify miniature gangs—and a form of violence that may be even more difficult to tamp down than what came before it.

Names like “Crips” and “Bloods” conjure images of old-school, dyed-in-the-wool gangsters orchestrating crime through disciplined, hierarchical posses. But that’s not modern New York. “These are all young kids,” says Ric Curtis, chair of John Jay College of Criminal Justice’s anthropology department and one of the authors of Hynes’s study. “They may claim allegiance to ‘Bloods,’ but it’s a bunch of neighborhood guys who got together and decided to call themselves Bloods.”

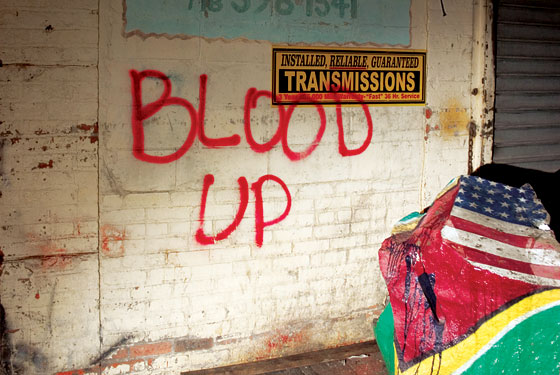

They’re still gangs, to be sure, but the label is more stylistic than organizational. The distinction’s important: Instead of a couple of big gangs, there are dozens of small, clannish sets, often made up of literal cousins and next-door neighbors. Walk around Brownsville and the signs cry out from the walls. There are spray-painted B’s and C’s with arrows pointing upward, meaning “Bloods up” or “Crips up.” But that’s just the beginning. There’s a laundry list of acronyms—GCC, L*C, MAC, COC$, all groups calling themselves Crips. Northeast Brooklyn is chock-full of these mini-gangs, and they’re fighting.

The question is, what are they fighting about? Yesterday’s drug violence was a means for dominating the market and protecting the product from stickup artists, who targeted street-level salesmen. Today, dealers sell primarily to known customers and avoid risky street-level sales—and, thus, should be less likely to get involved in competitive gunplay. So why all the killing? “The idea that the shootings are drug-related has some truth to it, but it’s overstated,” says John Jay’s Greg Donaldson, who wrote a 1993 book about Brownsville and is working on a follow-up. “What they are, are people who are armed because they’re in the drug trade, but then it’s often personal—somebody said something to someone’s girlfriend.”

That’s what happened to Danny’s best friend. Danny, a baby-faced 19-year-old who didn’t offer his last name, has spent his whole life in Brownsville’s Tilden Houses. He claims not to be in a gang, but “Crips” is scratched into the wall on his floor at Tilden—and he carries a chain of black rosary beads, which the D.A.’s office says is a gang sign that comes from prison, where guards can’t confiscate religious iconography. Danny does admit to having a gun, and he’s puzzled by questions about how he got it. “I took it off somebody else,” he says matter of factly.

Two years ago, Danny’s friend was hanging out on Rockaway Avenue, the commercial strip that runs alongside the projects, when he noticed a girl coming out of a bodega across the street. Danny’s buddy hollered at her. Her boyfriend didn’t like it. They argued. Danny’s friend shot the other kid in the butt. He survived, but by morning, Danny’s friend was dead. The 16-year-old answered a knock on the door and faced a hail of bullets. “It had to be somebody he knew or he would’ve never opened the door, especially after what had happened,” Danny says. “He had his gun on him, but he didn’t even get to pull it out.”

Deanna Rodriguez, the D.A.’s gang-bureau chief, says the academics may be right that this sort of interpersonal beef among armed young men has caused the surge in violence in recent years. But the real concern, she argues, is that the small gangs are becoming entrenched—and starting to fight over drug-dealing turf. Maturing subsets of Latino gangs like the Latin Kings and Dominicans Don’t Play, she says, are particularly worrying—which may explain the city’s sharpest murder spike, in Bushwick’s 83rd Precinct, where a peace between area Latin gangs has fallen part.

“There were several gangs that were operating in one area, and they just coexisted,” says Rodriguez. “Each gang had their area, and they sold their drugs and were just able to exist independent of each other, because there was money to be made.” For some reason, she says, that’s broken down, and the same thing is happening all over the borough. “What appears on the surface to be a fight will have gang overtones. It’s not something you readily see until you investigate it. And then you have to look at the whole area and see what’s going on there.”

Ben Igwe, who runs the Family Services Network of clinics and aid agencies in Bushwick and Brownsville, believes the gang violence is intensifying because the poverty here is getting worse. The volume of food moving through his free pantry has nearly doubled in the last year, and he runs out of supplies every month. “Where are all the people who are priced out of Fort Greene and Bed-Stuy going? They come to Brownsville and Bushwick,” he says. “They move in and you have this higher concentration of poverty and they are stressed—and you are going to have conflict.” In 2006, Bushwick’s population jumped by more than 8,000 people, or about 7 percent, according to the Department of City Planning; 13 percent of the neighborhood’s residents lived in a different home than the year before. “There’s a pulse,” Igwe says. “You can feel it. And that stress ends in people acting out.”

The Police Department has vowed to stop the acting out, and a fresh crop of academy grads started flooding into the area over the holidays. But nobody who spends time in these neighborhoods thinks the gangs will be cowed. On Christmas Eve, a 12-year-old robbery suspect escaped from a police cruiser parked at a Rockaway Avenue corner when someone just walked up and opened the car door. “People are not afraid of police, and they’re not afraid of jail,” says Donaldson. He acknowledges that the cops’ war of attrition against organized crime brought murder rates way down at century’s close, but he argues no policing solution can hold permanently. “You’re not dealing with the root cause,” he says. “Nobody wants to hear about the root-cause thing, because it’s an old story. But nobody ever gave those guys jobs.”