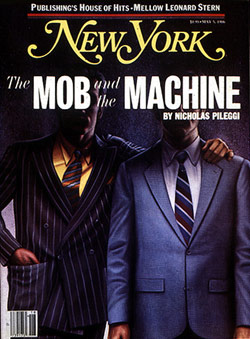

From the May 5, 1986 issue of New York Magazine.

FBI agents who have spent their careers memorizing the nicknames and roles of New York’s organized-crime hoods have suddenly found themselves thumbing through copies of The Green Book, the city’s official directory. It turns out that many mob middlemen, and even a few top hoods, have begun showing up in the current political scandals.

So many connections have been made that some agents have had to draw up color-coded charts (Gambino, blue; Lucchese, yellow; Colombo, pink; Genovese, red; Bonanno, green) to help them keep track of the complicated web linking the hoods and the city’s political machine.

“The mob has always had some influence in politics, and in the past, they even had their own candidates in one or two key spots,” said Ron Goldstock, head of the state’s Organized Crime Task Force. “But now we are beginning to see evidence of a pervasive presence. It’s practically open. We’ve even begun to see partnerships in which mobsters and city officials were in business together.”

Rudolph Giuliani, the U.S. Attorney in Manhattan, said the organized-crime groups have grown so emboldened that mob-linked companies have begun making campaign contributions on the books. “There was a day when hoods might have slipped money to people under the table,” Giuliani said, “but we’re beginning to find that many of the companies linked to organized crime have openly contributed to political campaigns”—the subject of yet another investigation.

The renewed concern about the influence of organized crime in city politics comes at a time when the mob itself is under pressure. In the last year, federal and state prosecutors have brought several big cases against major mob figures. And, perhaps because of the federal and state crackdown, a power battle has apparently erupted within the mob. The latest piece of evidence is the April 13 car bombing that killed Gambino crime-family under-boss Frank DeCicco.

Of the almost two dozen separate federal and local investigations that have been kicked off by allegations of bribery in the city’s Parking Violations Bureau, at least a half-dozen now involve links to the mob. These include:

• The secret real-estate partnership between former Department of Transportation commissioner Anthony Ameruso and Angelo Ponte, an alleged mobster.

• The curious comings and goings of reputed mob money-launderer Michael W. Callahan, who was one of the few non-family members to visit former Queens borough president Donald Manes in the days just before Manes killed himself.

• The relationship between indicted Bronx County Democratic leader Stanley Friedman and a top aide, Paul Victor, the son of an organized-crime member. Victor was a secret partner in a printing firm that had no plant facilities yet received a total of $250,000 from Friedman’s campaign committees.

• The relationship between City Planning commissioner Theodore Teah and Robert Hopkins, a six-foot-five-inch, 250-pound organized-crime policy operator who has been charged with ordering the murder of a mob rival.

• The connections between former Taxi and Limousine commissioner Jay Turoff and a casino employee with reputed links to the mob.

Other investigations sparked by the political scandals are trying to learn why $22 million in city contracts was awarded to a plumbing company that employed Gambino crime boss John Gotti and whose owners were indicted last June for obstructing justice in a heroin case involving Gotti associates; why a towing company linked to a Lucchese consigliere has kept its exclusive Department of Transportation contract with the city for five years; and whether mob influence was involved in a controversial landfill and marina project in Queens. One of the project’s partners, a man who is under indictment for tax fraud, ran a catering operation and restaurant that’s known as a Gotti hangout.

What’s more, several politically linked mob cases that were under way before the municipal scandals broke are now being seen as part of a larger pattern. In Queens, former State Supreme Court judge William Brennan was convicted in December of taking a bribe from an organized-crime hood to fix a mob case. Brennan also showed up as a partner in the real-estate deal involving Ameruso.

And in the Bronx, Democratic state senator Joseph Galiber is awaiting trial with reputed mob soldier William “Billy the Butcher” Masselli. The two are charged with running a phony minority trucking firm that allowed a company run by former secretary of labor Raymond Donovan to qualify for the $186 million 63rd Street tunnel contract.

More investigations of the links between the mob and the machine are being opened almost weekly, and—in light of what’s come out recently—the Feds are reopening cases put aside several years ago. For example, they’d like to know more about the 1983 mob-style death of Rick Mazzeo, a real-estate director for the Department of Marine & Aviation. Mazzeo’s body was found in the trunk of a car in Greenpoint just before he was supposed to testify about ripoffs of city leases.

“We’ve found wiseguys just about everywhere we looked,” said Raymond Dearie, the former U.S. Attorney in the Eastern District, who was recently appointed a federal judge.

Following the mob’s political trail is a complex, touchy business these days because the connections are usually subtle or hidden. Working through lawyers, union leaders, and businessmen, the hoods have managed to make their contacts and work their deals without resorting to strong-arm tactics. The big guns on both sides—the top mobsters and the top pols—rarely need to get involved. The arrangements are made through middle-men and aides, people who have forged friendships in childhood, in campaigns, in various business deals.

“Few hoods are in power themselves,” Goldstock said, “but they are sometimes behind the people in power. The real connections seem to come between the pols, business associates, and certain union support. Almost every politician needs some kind of business and union support. The pols need money, phone banks, lawyers to safeguard the polls, manpower to get petitions signed, buses to get people to the polls, and flatbed trucks for loudspeakers.

“We’ve found wiseguys just about everywhere we looked,” claims one former U.S. Attorney.

“The person running for office may not directly have to make any deals, but his campaign people do. The friendships and relationships are established. Then, when the candidate gets elected, he usually appoints the same people who have helped get him elected. They may not be appointed to the top, showcase posts, but they do get the jobs where they can affect what goes on.”

The story of the mob and the machine goes back at least to 1931, when Lucky Luciano sent two gunmen to see Harry C. Perry, the co-leader of Manhattan’s 2nd Assembly District. The gunmen asked Perry to step down in favor of Albert Marinelli, a pol in Luciano’s debt. Perry complied.

In the years that followed, the mob’s influence became brazen. During a Tammany Hall fight in 1941, Frank Costello dispatched gunmen to Tammany clubs around the city to help elect Costello henchmen as district leaders. Within a year, Costello’s men made up the majority of Tammany’s governing board. Not long after, Costello was getting calls from judges thanking him for his support in getting them court nominations.

The mob’s interest in the business of government grew more sophisticated in the sixties and seventies, when government became big business. Food programs, day-care leases, waterfront development, urban-renewal contracts, and minority-enterprise businesses, for example, offered great opportunities for theft. By the late seventies, the city’s real-estate boom and the mob’s hold on key construction unions helped put organized crime in a position to drive up the costs of building in New York. The mob became a participant in the city’s booming economy.

Until recently, no one seemed to be looking, and few people seemed concerned that the mob had worked its way into the machine.

For years, the Thomas Jefferson Democratic Club of Canarsie, in Brooklyn, has been the most powerful clubhouse in the city. Brooklyn Democratic boss Meade Esposito headed the club for fifteen years, until his retirement in 1984.

Esposito’s connections to organized-crime hoods are well known. His name popped up repeatedly in a bugged junkyard trailer used as a headquarters by Lucchese capo Paul Vario in 1972. The tape led to the convictions of 40 organized-crime hoods and 21 corrupt policemen. Esposito has never tried to hide his connections. He says he knows some of the city’s crime chiefs because he grew up with them. During his years as a bail bondsman, he bailed them out. He denies, however, that they have any influence with him. “I never do a thing for them,” he says.

Nonetheless, in the 261-acre Brooklyn Navy Yard, for example, where Esposito long held the patronage key, it was discovered a few years ago that the mob had somehow managed to take hundreds of thousands of dollars in shipyard elevator-repair contracts, despite the fact that the repair company had no employees and operated out of the rear of a Brooklyn café. The contracts were rescinded.

“Things have been going on for years,” said Ed McDonald, the chief of the Federal Organized Crime Strike Force in Brooklyn. “But no one seemed to be paying any attention. We had a series of convictions involving wiseguys and politicians; we had murders, disappearances, and congressmen writing mercy letters to judges on behalf of vicious mob capos; and, after a paragraph in the papers, very little seemed to happen. The bad guys were replaced by new bad guys, and the system continued without missing a payoff.”

As a result of the current investigations, however, many of the cozy relationships between the mob, its middle-men, and the city’s pols are being looked at with new suspicion.

The career of former Department of Transportation commissioner Anthony Ameruso, 46, offers a fairly typical example of how the mob and the machine were quietly linked until the recent investigations opened everything to scrutiny. Shortly after Mayor Koch’s election in 1977, Ameruso was appointed DOT commissioner, despite being rejected by the mayor’s own screening panel. However, Ameruso did have the support of Meade Esposito.

Ameruso remained a commissioner—in charge of the Parking Violations Bureau, among other agencies—even though he was the target of several inquiries. His name popped up on FBI tapes as far back as 1979, when two mobsters, Nat and William “Billy the Butcher” Masselli, talked about a supposed “meeting with Ameruso” and stressed that “nobody is supposed to know about it.”

There was a Department of Investigation probe after the DOT awarded lucrative car-towing contracts to Midtown Collision, a company that listed among its employees Christopher “Christy Tick” Furnari, a consigliere in the Lucchese crime family.

Ameruso was also questioned about allowing a highly coveted no-parking sign to be put outside a Mulberry Street restaurant owned by Matthew “Matty the Horse” Ianiello, an organized-crime capo who was convicted in December in federal court of skimming millions of dollars from his restaurants and topless-disco operations.

In 1984, Ameruso had even been put under surveillance by the city’s Department of Investigation after officials received reports that he had accepted cash kickbacks from Federal Armored Transport, a mob-connected armored-car company that won a $107,000 contract with the PVB. The inquiry began after Federal’s contract was rescinded because two of its guards were arrested carrying unlicensed guns. What’s more, officials discovered that Federal’s PVB contract called for the company to collect money throughout the city and carry it to banks, even though Federal had no insurance and no gun permits.

Though Ameruso managed to survive all these inquiries, he resigned in January after news broke of the bribery scandal in the PVB. Ameruso himself was not directly tied to the PVB scandal, but as the commissioner in charge of the bureau, Ameruso said, he felt responsible. Koch publicly regretted the loss of the DOT commissioner.

Shortly after Ameruso left office, however, an informant called the FBI and claimed that Ameruso had been a secret partner with Angelo Ponte in a parking lot at the corner of Spring and Varick Streets. Ponte, who’s a private carter and one of the owners of Ponte’s Restaurant in lower Manhattan, was identified in state hearings last year as a member of the Genovese crime family.

After selling the parking lot in 1985, the partners (there were six in all) made $2.3 million on a 1981 investment of $505,000, according to investigators. Ameruso himself made $148,000 on his $40,000 investment. In addition to the potential conflict of interest inherent in the city’s parking czar going into the parking-lot business, Ameruso “intentionally manipulated the price of his investment” so he wouldn’t have to report it on the city’s financial-disclosure form, according to former U.S. Attorney John Martin, who was appointed by Koch to investigate city corruption.

Ameruso’s lawyer, Nicholas Scoppetta, denied that his client has engaged in wrongdoing. He said that Ameruso knew Ponte from eating at Ponte’s restaurant, and that he got involved in the parking-lot deal at the suggestion of a Queens banker, Michael Cousins. Ameruso has not been charged with any crime.

In Queens, federal agents are very curious about the relationship between Donald Manes and Michael W. Callahan, a mysterious, 47-year-old organized-crime associate. While Manes was recuperating from the suicide attempt and heart attack that were apparently brought on by the PVB scandal, Callahan visited him twice—the last time eight days before the former county leader killed himself.

Callahan’s criminal record goes back at least to 1982, when he was indicted for setting up a money-laundering scheme for the mob. He pleaded guilty to a lesser charge and identified himself as a close associate of Joseph Trocchio, a member of the Genovese crime family.

Agents who were watching the Manes house said Callahan tried to leave without being spotted, by slipping out the back door. He then went to pay-phone booths several blocks away and made several calls after nervously looking around to see if he was being observed.

Callahan and Manes were certainly friends, often hopping off together to Atlantic City in a helicopter. What’s more, Callahan sold Manes a Westhampton Beach house for the bargain price of $204,000, even though it had been listed for $295,000 by local real-estate agents. Investigators would like to know why Callahan was so generous toward Manes concerning the house, and they’d like to hear about any other business dealings between the two men. In addition, they want to know whether Manes viewed Callahan’s last visit as friendly.

Agents have also gone back to look at Manes’s appointment in 1978 of Dominick Santiago as director of the city’s Public Development Corporation, an agency charged with attracting new industry to New York. Santiago led a remarkable double life, one that in itself epitomizes the close connections between the mob and the machine. As Dominick Santiago, he was Carlo Gambino’s godson, ran trucking companies suspected of mob infiltration, and served as president of Independent Local 3108 of the Brotherhood of Carpenters. Also under that name, he was arrested, indicted, and given a six-month federal-court sentence in 1975 for embezzling $500,000 in pension funds. Under the name Nick Sands, however, he became a Democratic state committeeman in the 33rd Assembly District in Queens; he got his Public Development Corporation appointment; he was a fund-raiser for Governor Carey; he became a member of local School Board 24; and he organized a 1979 fund-raiser for Representative Geraldine Ferraro.

On May 8, 1980, two men opened fire on Santiago/Sands as he left his home in Middle Village, Queens. He was hit nine times, but he survived and has since kept a low profile, according to the Feds. Today, agents are trying to figure out why so little was done to investigate the matter.

After the shooting, Manes said he was “shocked” to learn about the background of the man he had appointed: “He came well recommended as a union president and school-board member and a member of the State Democratic Committee.”

Agents watching the Manes house saw the mob associate slip quietly out the back door.

In another investigation in Queens, District Attorney John Santucci is looking at the dealings of Arc Plumbing and Heating, an Ozone Park outfit that had $22 million in city contracts, including the contract to redo the restrooms as Shea Stadium. Santucci first came upon the connection between John Gotti and Arc in 1981, when the D.A.’s office installed the first wiretap in Gotti’s headquarters. Lieutenant Remo Franceschini, who heads the Queens D.A.’s squad, turned over his original work on the Gotti case to the Eastern District, where Gotti is currently on trial on racketeering charges. But the information about Gotti’s employment at Arc, which had been approved by the state’s parole board, apparently never made its way to city officials: Millions of dollars in city contracts were awarded to Arc, even though the mob connection had been established.

“As a cop, I’ve been watching wiseguys for 30 years,” Franceschini said, “but I’ve never seen them so bold. It’s practically out in the open. I was amazed to find that Arc had over $22 million in city contracts, but I’m more amazed every day.”

Santucci is also looking into a case involving a controversial landfill and waterfront development along Cross Bay Boulevard in Howard Beach. Among the partners in the project are Frank Russo, the owner of the Villa Russo, a Queens restaurant and catering hall that was a Gotti hangout. (For a time, Santucci ate there, too.)

“We began looking into the landfill and waterfront development after complaints about the way in which zoning variances were put through,” Franceschini said.

Three weeks ago, the state attorney general charged Russo, in a twelve-count indictment, with evading nearly $50,000 in state and city sales taxes. Russo has pleaded not guilty in the case.

Sometimes, if mobsters can’t go directly into partnership with members of the city’s political elite, they hire them as lawyers. There’s nothing improper about a politically active lawyer having a mobster as a client. But prosecutors argue that some mobsters work through their lawyers to make their influence felt in the city.

Bronx Democratic leader Stanley Friedman is an associate in a law firm—Roy Cohn’s firm—that is known for its vigorous defense of organized-crime members. Friedman, who has been indicted for bribery and stock fraud in the aftermath of the PVB scandal, is the kind of public official who boasted about his connections in city government and his mastery of the bureaucracy. To a great degree, Friedman was right about his political clout, but he also picked up a number of associates along the way who are now coming under scrutiny.

For example, the Manhattan district attorney’s office is examining the connection between one of Friedman’s top aides, Bronx City Planning commissioner Theodore E. Teah, and Robert Hopkins, a mob policy operator charged last month with ordering the murder of a mob rival. Teah, a former employee of Roy Cohn’s law firm, was Hopkins’s lawyer. After the revelations about Hopkins came out, Teah said he was “aghast” to learn of the murder charge and of his client’s reputed mob ties.

Investigators for Manhattan District Attorney Robert Morgenthau, however, say that Hopkins’s reputation as a mob policy operator was widely known in the city. Hopkins himself is hard to miss. He stands six feet five inches tall and weighs 250 pounds. He fancies himself a rock star and once rented the Palladium for $15,000 to throw a party for J. J. Jackson, an MTV V.J. He tipped disco doormen with Cartier watches. And he shared a $2-million, fifty-ninth- and sixtieth-floor duplex at Trump Tower with the son-in-law of Lucchese crime-family soldier Peter “Petey Beck” DiPalermo.

Teah had Hopkins’s power of attorney, and the lawyer’s name appears on a sales agreement for a building Hopkins bought on City Island that has since been used to raise the million-dollar bail in the homicide case. Teah has explained that his name appeared on the sales papers only because Hopkins was out of town at the time of the signing.

Other questions about Teah have been raised recently. Federal prosecutors are looking into Teah’s $29,000-a-year job as president of the Bronx Broadcasting Company, a corporation set up by Bronx Borough President Stanley Simon to produce community programming for a cable system that doesn’t yet exist. Teah, who was Simon’s campaign manager last year, is also being investigated by a federal grand jury in connection with the giving of more than $168,000 of Simon’s campaign printing work to a Yonkers company, Town Hall Printing. The firm is owned in part by two of Friedman’s closest aides—Paul Victor, counsel to Friedman’s Democratic County Committee, and Murray Lewinter, the secretary to the committee. Town Hall’s lawyer told prosecutors that Victor and Lewinter got $15,000 in profits last year on a “handshake” deal that brought the political printing work to the firm.

“So far, we have found that Town Hall has no printing plant and does none of its own printing,” one investigator said. “It’s just a telephone number in a Yonkers office that passes its printing work on to other firms.”

Teah denies knowing that Victor and Lewinter were the secret owners of Town Hall, and he says he did not authorize payments to the firm.

Paul Victor, the cops say, is “well connected.” He is law chairman of the Bronx Democratic party and counsel to the Public Administrator’s office of the Bronx Surrogate Court. In 1978, as the party’s parliamentarian, Victor made the key decision that allowed Friedman to take over the Bronx Democratic organization. In 1984, Governor Cuomo appointed Victor to the state’s Law Revision Commission.

Victor is also the son of Genovese crime-family soldier Albert “A1 Sappo” Viggiano.

Despite his involvement in civic affairs, and his influence in picking judges, prosecutors say that much of Victor’s income has come from his representation of organized-crime figures.

Jay Turoff, the city’s former Taxi and Limousine commissioner, is currently being investigated for awarding 100 taxi medallions valued at $100,000 each to a company in which he may have had an interest; for giving a lucrative taxi-meter contract to a family friend; for steering TLC business to a Brooklyn Democratic-party printer; and for improperly borrowing $244,000 from a taxi-industry credit union that allegedly paid Turoff a $30,000 bribe. His mob links, his comp trips to Atlantic City, and his penchant for blackjack are something else.

Through his gambling activities, Turoff became friendly with Charles Meyerson, an employee of the Golden Nugget in Atlantic City. Federal authorities in Brooklyn are now investigating whether Meyerson allowed Turoff to secretly buy into a cab company in Yonkers. Turoff’s lawyer, Edward Rappaport, denied any wrongdoing by his client.

Meyerson himself is under investigation for allegedly arranging lines of credit at the Golden Nugget for known mobsters and for sneaking them into the casino.

Until the muncipal scandals broke, law-enforcement authorities had rarely focused on the connections between the mob and the machine. All that’s starting to change now. The effects of the new, get-tough approach are likely to be evident in the next few months as the various investigations continue rooting out trouble. Still, some authorities think the effort may be too little too late, at least as far as organized crime is concerned.

“Today, the hoods are almost indistinguishable from the good guys,” said former federal prosecutor Raymond Dearie. “Their businesses have been assimilated. Yesterday’s hijacker is going to college and is armed with a telex machine instead of a gun. The real story in the next few years will be the extent of this new mob’s influence in the city.”