From the March 27, 1972 issue of New York Magazine.

At 4 p.m. one Saturday last month, a tall, thin, eighteen-year-old youth called Judd was standing on Daly Avenue in the South Bronx fingering the butt of the sawed-off shotgun that jutted from the top of his dungarees. Flanking him on either side were two other young men, Mike and P.I., both seventeen, both with pearl-handled .22-caliber pistols in their belts. All three wore the colors of a Bronx street gang called the Black Assassins.

Facing them not more than five feet away was an eighteen-year-old youth named Alvin, president of the Majestic Warlocks. Standing alongside Alvin were Power, 22, and Butter, 20, both leaders of a group called the Old Timers, a sort of alumni club for old Warlocks. If any of these three was packing weapons, they were well concealed.

Across the street a boy of about fifteen, a Warlock, could be seen crouching in a doorway, the barrel of a rifle barely visible in the shadows. Two more Warlocks had circled around a car and stood side by side on the curb behind the Assassins, their right hands hidden in the folds of their jackets. Along Daly Avenue, ordinarily one of the most heavily patrolled neighborhoods in the Bronx, no squad cars passed by. (Cops, gang members swear, know when to lie low.)

It was a faceoff on the Assassins’ home turf, the long block on Daly Avenue between 180th and 181st Streets. The confrontation was occasioned by an incident the night before at a party in the Warlocks’ basement clubhouse several blocks away up the snake-like hill that borders Crotona Park. The details are obscure, but the incident apparently involved the roughing-up of the girl friend of a Black Assassin who had had too much to drink. The Assassins had fired two shots, No one had been hurt. The only damage, apparently, was to both gangs’ pride.

On the street Saturday afternoon Judd was the first to speak.

“You want to talk?” he said. “We’re ready.”

Power spoke for the Warlocks. He was at least an inch taller than Judd and several pounds heavier. He and Butter had both been presidents of the Majestic Warlocks in their day. Now, as Old Timers, their concerns ranged over the entire Warlock tribe, which includes four separate divisions in four parts of the Bronx. They go wherever trouble develops.

Power opened his denim jacket at the hip, showing no weapon. “We’re clean, man,” he said.

“Well, we’re not,” Judd said, with an uncertain smile.

“How you gonna talk with a piece in your belt?” Power said. He stepped back a foot or two and the entire Warlocks contingent seemed to fan out very slightly.

At that moment a lean, young, well-groomed Puerto Rican who had been leaning against the wall of a nearby apartment house came forward. José Ramos, a 21-year-old street worker who had been reassigned to desk duty in Brooklyn in an office of the Youth Services Agency after a recent administrative shakeup, was on his own time, but his presence on Daly Avenue that Saturday last month was no accident. Through sources painfully built up over time, Ramos had learned of the incident the night before and of the confrontation that figured to follow. Both Judd and Power knew Ramos as “T.C.,” the nickname he had used since his own day as leader of a Bronx gang called the Royal Javelins.

Ramos stepped between the two groups and spoke quietly for a few minutes. He persuaded Power, Butter, and Alvin to talk the matter out in the Assassins’ basement headquarters. It was a considerable concession; on the street the advantage was theirs. As the six youths and Ramos headed down an alleyway to the Assassins’ meeting place, at least 25 previously unnoticed Warlocks suddenly emerged—from shadowed doorways, out from behind parked cars, clambering down from fire escapes.

Inside the Assassins’ basement headquarters—two dimly lit rooms with painted stone walls and several lumpy chairs and sofas salvaged from sidewalk junk heaps—the Warlocks remained standing.

“We didn’t come here to make you apologize,” Power said. “We just came for an apology.”

Judd became angry. “If anyone has apologizing to do …”

Butter tried his hand. “Look,” he said, “let’s get this down to the brothers who did what to who.”

“We don’t work that way,” P.I. said. “We settle scores as a group.””Didn’t you sign the ‘Family Treaty’?” Ramos said quietly to P.I.

A long silence followed. Then both sides started talking at the same time, not arguing, just talking, and soon after the quarrel seemed resolved, with each side apologizing to the other and handshakes all around. Then the Majestic Warlocks departed in peace.

Thus, thanks only to the delicate intervention of a city worker under no obligation to be there, and thanks to his timely mention of a “Family Treaty” of doubtful force and durability, a fragile, uneasy calm prevailed on Daly Avenue that cold afternoon last month. Otherwise, Daly could easily have become what several other streets in the South Bronx have already become in recent months and what other streets may very well become before the year gets much older—the setting for a brutal showdown between quarreling youths gathered in street gangs. Without much notice, it seems, street gangs have again become a problem in New York, this time on a scale and with a potential for violence that may be unprecedented—the near certainty of gunplay and a high probability of mindless, trivially motivated homicide.

There are at least 70 separate street gangs in the Bronx alone right now. Some of them, like the Majestic Warlocks, have affiliations with others bearing the same name in various neighborhoods. Others, like the Black Assassins, are independent. In size any one gang will vary from about two dozen to 200, and no one dares estimate how many members the 70 have, combined—4,000 is a reasonable guess.

In the South and East Bronx, predictably, most gangs are all black or all Puerto Rican. But mixed gangs of blacks and Puerto Ricans are not uncommon. In the North Bronx, most gangs are all white. The Five Percenters profess themselves Black Muslims, but most groups have no truck with ideology. (Despite some encounters between blacks and whites, race has not been an important factor in gang action thus far, but the potential is obviously there.)

Chains, knives, fists, and, of course, those crude and unreliable homemade affairs called zip guns were the staples in the more vicious gang wars in the 1940s and 1950s. Today there is scarcely a gang in the Bronx that cannot muster a factory-made piece for every member—at the very least, a .22-caliber pistol, but quite often heavier stuff: .32s, .38s, and .45s, shotguns, rifles, and—I have seen them myself—even machine guns, grenades, and gelignite, an explosive. One gang, the Royal Javelins, has acquired some walkie-talkie radios.

“… Heroin destroyed the gangs a decade ago. But these new gangsin the Bronx aimed a reign of terror at the drug pushers …”

Through the efforts of a remarkable street worker named Eduardo Vincenty, a member of the ten-man “crisis squad” set up in 1970 within the Youth Services Agency of the city’s Human Resources Administration, a massive non-aggression pact among Bronx gangs was worked out last fall. Beginning with five gangs from the East Tremont area, Vincenty orchestrated the formation of a “Family Peace Treaty” binding the signatories to talk out differences first before escalating a quarrel and, if talking couldn’t settle a matter, to get gang members to settle their differences on a one-to-one basis, with fists only, in a closed room. By November 29, 1971, Vincenty had lined up 68 gangs to sign the Family Treaty.

But as this is written, the Youth Services Agency’s ten-man crisis squad is no more, disbanded in an administrative shuffle just last month. (It was in this shuffle that José Ramos was pulled off the Bronx streets and sent to a desk in Brooklyn.) And Vincenty himself, at 26 a five-year veteran mediator of street quarrels, is under doctor’s orders to stay in his three-room apartment on Marmion Avenue for now. On January 21 of this year Vincenty took a .22-caliber bullet in his temple as he tried to stop a fight on Tremont Avenue in the West Farms area.

Just how fragile a peace prevails among Bronx gangs was shown only eight hours after José Ramos got the Majestic Warlocks and the Black Assassins to shake hands. On Sunday morning, February 27, just after midnight, a suspected Five Percenter named Emilio White, alias Emilio Esau, was gunned down on Vyse Avenue just up the block from the Assassin clubhouse. The two bullets that entered White’s back, according to police of the 48th precinct, were fired from two different .22-caliber pistols of the same make, the kind that comes with a pearl handle. The bullet that entered White’s forehead just above the bridge of the nose was a .32, fired at point-blank range. Witnesses to the shooting picked out three faces in a gallery of photos at the station house. All three were identified as Black Assassins—P.I., Mike, and a third whose name the police did not have. Reportedly, it was Judd.

By midafternoon Tuesday, February 29, P.I. and Mike had been arrested and charged with first-degree murder. The cops were said to be looking for Judd. The next day, a friend saw Judd slouching in the shadows across the street from the Bronx Boys Club on Hoe Avenue, a favorite hangout of many gang members. Judd looked as though he hadn’t slept for days.

“Do you know the cops are after you?” the friend asked.

Judd smiled the same uncertain smile he had on Daly Avenue as he faced the Warlocks. “For the dude that was hit last weekend? Yeah,” Judd said. “I didn’t have anything to do with it. Neither did the two they got yesterday.”

The friend, who clearly didn’t believe him, asked, “Are you going to split until things cool off?”

“I know the detectives around here,” Judd answered, as he started walking away. “There are only three of them who could spot me.” Then he said, over his shoulder, “The Man better get all the leaders before summer, ‘cause if he doesn’t, nobody’s gonna stop us then.”

It’s easy to see why New Yorkers haven’t had to worry about street gangs in any serious way for more than a decade. By 1962 the group tensions and violence that previously arose in quarrels over “turf” and girls were all but totally relieved by a new kind of ghetto street worker—the dope pusher. Heroin destroyed the gangs.

It’s a good deal harder to say what began to bring the gangs back. One major factor, clearly, was the emergence of the Black Panthers, the Black Muslims, and the Young Lords—groups of young people with at least the semblance of a program, a taste for violent confrontation if necessary, an interest in change, and a strong intolerance of hard drugs. By the late 1960s it seemed as if half the blacks and Puerto Ricans in the Bronx had become members of, or at least identified strongly with, such groups.

Since then, calls for revolution and hassles over political doctrine appear to have lost their appeal. They offer little to a sixteen-year-old with a father or a brother or sister who is a heroin addict. Slowly, neighborhood gangs of young people, mostly teenagers but an astonishing number no older than ten, began to reappear.

At first, these new gangs—or “cliques” as they prefer to be called—showed little interest in violence just for the hell of it. When they began, much of their anger was tightly focused on the dope traffic in their midst. Independent of one another, many gangs began a reign of terror against pushers. By early 1970, when the city government awakened to their existence, these new gangs had pushed at least a portion of the heroin trade westward, across the Grand Concourse.

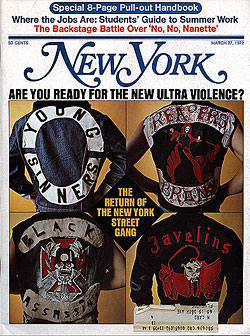

Instead of staging full-scale rumbles over turf here and there, cliques began sending out tentative peace feelers to one another. In mid-January of 1971 the outlines of a remarkably sophisticated political alliance began to take shape. A coalition known as the Brotherhood was forged by Ruben Maldonado, then president of the Royal Javelins, and Robert Williams, president of the Peacemakers, with the help of Eddie Vincenty, whom they enlisted as an utterly trustworthy adviser and middle man. At the time, the Javelins and the Peacemakers were the two most heavily armed gangs in the Bronx, with single large divisions in the East Tremont area. Within a month they were joined by the Young Sinners, the Reapers, and the Black Spades.

Outside agencies quickly became interested in the Bronx gangs. The Young Lords and Será, a Federally-backed Spanish-speaking anti-poverty group, joined with the city’s Youth Board to open a storefront center for the Ghetto Brothers, a large and vocal clique in the Southeast Bronx. Various neighborhood groups with Federal funds began making overtures to gangs in the Tremont and Hunts Point areas.

But other outside groups began paying attention too. Within days of a Daily News story on the Brotherhood last November, various New York equivalents of Krupp and Skoda—munitions salesmen dispatched by the organized black underworld, some gang members are convinced—were filtering through the Bronx ready to deal in hand guns, machine guns, grenades, and explosives. Earlier this month, a large clique in the Northeast Bronx concluded a deal—one of the gang insists it was with the Black Panthers—for four high-powered rifles and “several” .38 revolvers. Reported price: just under $300.

With Bronx street gangs, as with nations, arms races tend to lead to disaster. As a result, the delicate Family Treaty negotiated by Eddie Vincenty last November is rapidly losing whatever force it had. The death of Emilio White on Vyse Avenue last month is no isolated case. Some recent items:

February 18: three all-white gangs from north of Fordham Road go south, with machetes, looking for Black Spades. The Spades are nowhere to be found; they are up north on the white gangs’ turf, with guns.

February 24: Robbie Williams, 21, former Peacemaker president and co-founder of the Brotherhood, is stabbed outside his home on Vyse Avenue. He is released from the hospital four days later, just in time to see his new daughter baptized.

March 12: Anthony Rennie, a fourteen-year-old Black Assassin, is shot to death trying to negotiate a truce between his gang and the Shades of Black.

March 13: the Young Saigons, a clique from 162nd Street, beat up on members of the Seven Immortals in the street near Morris High School. Julio, president of the Immortals, heads to the Saigons’ clubhouse to negotiate a peace, but nobody listens.

The ability of the Bronx police to deal effectively with today’s well-armed street gangs may have been grievously compromised in a recent and bizarre event. On February 29, according to some gang members who say they were present, seven uniformed policemen shouldered their way into an apartment on Westchester Avenue, headquarters of the Seven Immortals clique, searched it, and in the process destroyed a television set and a record player. On their way out, the Immortals say, the police paused long enough to scrawl an obscene message on the wall. Their testimony is supported by Leonard Levitt, a reporter for the Time-Life News Service, who lodged a personal protest with police authorities after the incident. Two days later, on March 2, two members of the Seven Immortals and eight members of another clique, the Slicks, were arrested as a result of an altercation inside the Simpson Street police station. Two cops were reportedly injured. Members of the Immortals and the Slicks charge that the attack in the Simpson Street police station never took place. They claim the whole incident was a frame-up, part of a continuing policy of police harassment.

Gang attitudes toward the police are a predictable compound of cynicism, mistrust and fear. The litany of grievances ranges from major brutality to minor harassment at cops’ hands. Cruising police cars, more than one gang member says, habitually dart down a side street to intimidate a lone youth, only a lone youth, if he happens to be wearing his “colors”—his gang jacket. Various members of the Royal Dutchmen, Young Sinners, and Sixth Division Black Spades claim to have been frisked by cops without cause, then had their jackets “confiscated” and told not to be caught wearing colors again. Over the years, gangs have learned to cope. They learned, among other things, that police were jotting down names they heard on the street and compiling dossiers at the station house. To make the task harder, virtually all gang members take a nickname when they join a clique. Even a gang member’s closest friends may not know, or care, what his given name is.

“… Their chief form of punishment, administered in high seriousness, is a physical beating—of unpredictable severity …”

But many gang members take a surprisingly pragmatic view of the police. Cops, it seems, occasionally have their uses. Last November, police of the Simpson Street station began to question members of the Mongols, a gang centered around Bryant Avenue and Westchester Avenue, about a murder that had occurred a few days before. Some Mongols, suspecting that their own president, Lucky, had fingered some of his own people, began to plan an insurrection against his leadership. To clear himself of their suspicions, Lucky went to the police and offered to tell them what he knew of the crime. The police went along with him, made an arrest on the basis of his testimony, and cleared the Mongols they had questioned. In so doing, the police got Lucky off the hook.

Like the police, the schools, too, have their uses, but the schools may not be so reliable. According to Spectra, president of the Imperial Dutchmen, a member of his clique went to the principal of his high school asking for protection from a rival gang in the school. The principal, Spectra says, advised the Dutchman to drop out permanently—”in the best interests of all concerned.”

The gangs have built a rigid, almost stifling social structure for themselves that stands in odd contrast to their near-total rejection of the outside world’s institutions. School doesn’t interest them—at least half the teen-age gang members in the Bronx seem to be either total or partial dropouts—and government betrays. On the surface, at least, they seem genuinely oblivious to the skin color of any man they regard as having an impact on their lives. Ted Gross, a black man who directs the Youth Services Agency, is contemptuously dismissed by many as an “Oreo cookie”—black outside and white puff inside. Lou Benza, a white assistant to Bronx Borough President Robert Abrams, is praised to the skies for his efforts to get gangs into storefront job-training centers. (It’s schools that the gangs put down, not education.)

The great majority of gang members live at home. Many easily manage to keep their gang affiliations from their parents; in many cases a “home life” can scarcely be said to exist. Some gang members often spend days, weeks, and months on end living in basement and apartment headquarters throughout the Bronx. This helps explain why gangs place such great importance on having a headquarters of their own—off the street and out of the way of the police.

The Royal Javelins solved their problem in an enterprising way. They proposed, to a somewhat uncertain and probably intimidated building superintendent, that they be given the use of a three-room basement apartment, in return for which they would provide protection to the building’s tenants and help keep the building clean. Thus far, the arrangement has been working out to the apparent satisfaction of the landlord, whose tenants are “taken off” in the streets less often, and to the Javelins, who seem to find pleasure in their “police” responsibilities.

Between 60 and 70 gangs now have clubhouses in the Bronx. Most of them are in basements, but a few, like those of the Javelins and the Seven Immortals, are in apartments. Most of the clubhouses are “leased” under arrangements similar to the Javelins’—in return for police and sanitation services, a place they can call their own.

But a fair number of other gangs, like the Reapers of 180th Street and Vyse Avenue, don’t have a headquarters and swear they don’t want one. “You’ll never get me in a clubhouse, brother,” said one young Reaper, nodding toward a passing police car. “There, the Man knows where you are, and he can come down on you whenever he wants.” He pulled a six-inch blade from the pocket of his denim jacket and said, “Sometimes you just can’t afford to get popped in on, know what I mean?”

Like all gangs through time, today’s Bronx cliques have their own notions of right and wrong. Their code accords, in a broad way, with that of the society outside. But their chief form of punishment, administered in high seriousness, is a physical beating—the severity of which is not always predictable. A girl associated with the Majestic Warlocks was recently disciplined for having taken heroin and having lied about it to members of the gang. To the Warlocks, the lie was as serious an offense as the deed itself. In the Warlocks’ basement headquarters, the girl, fully clothed, locked her arms around a column and received twenty strokes with a wooden paddle across her buttocks, ten strokes on each count. The Royal Javelins favor a garrison belt (not the buckle end) on the bare back. Several gangs use a wet towel.

Virtually all gangs collect weekly dues, usually a dollar or two, spent on firearms or for the improvement of the clubhouse. Failure to pay dues on time is almost always grounds for punishment. Other laws of conduct vary a good deal from clique to clique, but several rules are common to most. The use of marijuana, alcohol, and LSD is generally condoned, but systemic addictives like cocaine, heroin and amphetamines are taboo. First offenders are beaten. Repeaters are often given a choice between expulsion from the gang or a far more severe beating.

Robbery—of outsiders as well as of one another—was becoming a punishable offense in some gangs, on the theory, strenuously argued by the gangs that formed the Brotherhood, that coexistence with the community would naturally lead to community support for the gangs. It’s impossible to guess whether the idea could catch on—especially if the Brotherhood should dissolve.

The gang leaders, invariably called presidents, derive their authority from what can only be called strength of character. Above all, gang members respect courage. Virtually all presidents, and their war counselors (their seconds in command and first to strike a blow in a rumble), are articulate and, in their way, good administrators—good at delegating, good at getting things done. Presidents are seldom elected. They simply assume command, or are given it by acclamation, and they rule with unlimited authority until death, jail, or age intervenes, or until their magnetism gives out.

Some New Yorkers of a certain age—those able to nod knowingly at the drop of such names as the Amboy Dukes and the Redwings—will be tempted, as they ponder the return of the street gangs, to console themselves with the thought that the city has seen all this before. They will be kidding themselves. The city has never before seen so much factory-made firepower in so many youthful, organized hands. Others may think that an old ally in repressing gang violence, heroin, will return. That is less certain. The gangs in the Bronx have been down on hard drugs for several years now, and while no one can say whether they will stay that way, that is the present fact. No one, though, will assume that against the possibility of gang violence in the streets on a tragic scale there is a sensible, adequately financed plan equal to the threat.