Photographs by Cody Pickens

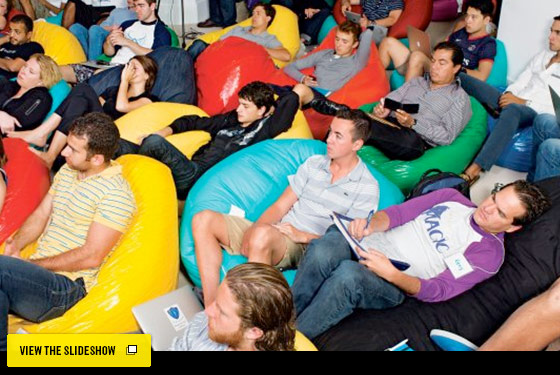

It’s just after breakfast, and the superheroes are gathering in a cavernous white-walled room amid a sea of brightly colored beanbag chairs. Once assembled, they place their hands over their hearts, face the portraits of Thomas Edison and Bill Gates hung high on the wall, and begin reciting their daily oath.

“I will promote freedom at all costs!” says Tim Draper, a venture capitalist with a microphone slung over his ear and a “Save the Children” tie brightening up his suit.

“I will promote freedom at all costs!” the heroes echo back.

“I will do everything in my power to drive, build, and pursue progress and change!” Draper calls out.

“I will do everything in my power to drive, build, and pursue progress and change!” they repeat.

“My brand, my network, and my reputation are paramount!”

“My brand, my network, and my reputation are paramount!”

These 40 young dreamers are the inaugural class of the Draper University of Heroes, Silicon Valley’s newest and most unconventional boarding school for aspiring tech moguls, located in San Mateo, California, just up Route 101 from Facebook’s Menlo Park headquarters. Most of the students are in their early-to-mid-twenties, and their backgrounds are a hodgepodge. There’s a Swiss wealth manager, a Stanford Ph.D., a former professional football player, and handfuls of directionless college graduates for whom Silicon Valley has the same mystique that Hollywood or New York holds for others. For the next eight weeks, they’ll apprentice at Draper’s feet, trying to pick up the tech world’s own brand of magical thinking.

In the process, they’ll be subjected to a fair amount of Draper’s zany-uncle humor. “A little wiggle and you’re good!” he says, miming a chicken dance as he shows the students how to choreograph part of their oath.

Draper, a tall, broad-shouldered bruiser with dark Cro-Magnon eyebrows and a mussed head of hair, finishes the oath and begins dividing the students into the teams they’ll stay on for the rest of the session. There are the Wonders, Titans, Lightning, Tornados, Angels, Magic, Lanterns, Phoenix, and Blizzard, and while it’s not quite clear what the teams are competing for, the students all titter at the idea of Hogwarts-style tribalism. Draper then asks that they introduce themselves with tweet-length autobiographies.

Collete Davis stands up. A petite Floridian, she came here after dropping out of Embry-Riddle, an engineering school. Her goal is to one day drive for IndyCar, and she wants to find a way to fuse her racing career with an entrepreneurial venture of some sort. Tim Draper has allowed her to attend for free in exchange for putting a Draper U. decal on her racing car and suit. After she gives her Twitter autobiography (“Hashtag American, racing driver, IndyCar, STEM education, creativity, family, passion”), she adds an aspiration from her personal bucket list. “You know that rap song ‘Wake Up in a New Bugatti’?” she says. “Well, because of where we’re at, I’d rather wake up in a Tesla!”

Draper lets out a guffaw, then pulls something metallic out of his pants pocket and tosses it across the room to Collete, whose eyes bulge as she sees what she’s been given: the keys to Draper’s Model S.

“Go ahead—take it for a spin,” he says. “Three blocks down that way.”

In the public imagination, Silicon Valley is all moments like these—luck and lucre falling out of clear California skies. But the day-to-day reality of being young in tech is often less glamorous. Even the hottest Internet companies have armies of junior grunts cleaning up code and doing corporate sales—the digital-age equivalent of scouting locations as a movie production assistant or making Excel spreadsheets as a junior Wall Street banker, but the magic of Silicon Valley wraps the sector—banal desk jobs and bold solo projects alike—in the banner of revolution. You feel special, even if you’re just answering the phone.

Draper University, which officially launched this spring, bills itself as a “school for innovators,” but it’s really an eight-week infomercial for the culture of Silicon Valley. Its goal is to infect students with the exuberance of tech and make them brave enough to leave a traditional career path for a stint in start-up land. Unlike at most tech incubators, you don’t have to have a company to enroll at Draper U. You don’t even have to have an idea for one. You just have to cough up the $9,500 tuition or, alternatively, pledge a small percent of your income for the next ten years. (So far, only one person has taken Draper up on the latter.)

Students at Draper are given two days of coding lessons and some elementary Excel practice, but most of what they’ll learn will be soft skills. Instead of teaching hard-core classes in Python and C++, Draper offers a cornucopia of team-building activities, which range from cooking and yoga classes to wilderness training and karaoke. At the end of the session, each student will be a “C.A.,” which stands for “change agent.” They’ll also be given two minutes to pitch a panel of investors on their business ideas. Like tech incubators Y-Combinator and TechStars, which are rewarded for their early support of start-ups with a fraction of future earnings, Draper stands to profit from any successes that sprout from the program. Draper’s son, Adam, has set up a tech accelerator, Boost VC, across the street from the school, where students can apply to polish their idea. When it’s ready for the big leagues, one of Draper’s venture-capital firms will be there, ready to pick up the company for funding. “It all helps itself,” he says. “These guys will all have leads for me.”

Draper, a third-generation venture capitalist, is a true believer in Silicon Valley’s greatness. He speaks in the earnest patois of the sector (disrupt, innovate, and dream would be in 36-point type in his personal word cloud), and a few of the investments that have earned him his fortune have been equally lofty; he remains a backer of Tesla and SpaceX, Elon Musk’s electric-car and space-exploration outfits. His firm made millions investing in Skype and Hotmail, two companies that may not have launched rockets but nevertheless became very profitable household names. Like any savvy investor, Draper’s portfolio contains a mixture of these companies—the ones that represent true innovation—and companies with more modest aims, ones that either piggyback on existing ideas and execute them in a slightly better way or that simply capitalize on consumers’ itchy-fingered desire for novelty. His recent investments include an ad-sales platform, a suite of “intelligent website marketing products,” a laser-tag iPhone game, and Bang With Friends, an app that helps Facebook users find partners for casual sex.

Draper decided to start his own school a few years ago, believing that what young people needed wasn’t practical start-up skills, which other schools already did a good job of teaching, so much as the will to be great and the courage to try their hand at riskier ventures. They would come in scared and curious and leave as courageous converts. “We want to be that frivolous university that can think about the future,” Draper says. “No serious university would teach this stuff.”

Draper’s school is typical of Silicon Valley writ large, in that thick layers of do-gooder idealism overlay the core capitalistic motives. During the first day of classes, I barely hear anyone at Draper U. mention money or the possibility of wringing Zuckerberg-like riches out of a tech start-up. Mostly, students speak about the value of Draper’s “network” and the vague “opportunity sets” that will result from getting to know so many prominent techies. Rather than thinking of this as an M.B.A. lite, or a computer-science boot camp, they view it as an eight-week lesson in dreaming big and thinking futuristically—essentially space camp without the rockets.

“I want these guys to be active performers in life,” Draper says. “If they’re bored in a classroom, they’re not maximizing their lives.”

A few weeks into the semester, I join the class for an afternoon of go-kart racing. After a morning lecture, lunch, and some time by the pool, students pack into a charter bus and head to a nearby indoor track, where they’re outfitted with racing suits and sleek helmets.

Alex Pulido is playfully trash-talking his classmates before the race. He’s a 24-year-old who played water polo and majored in urban studies at Stanford, then spent a couple of years doing freelance photography and other odd jobs before deciding to enroll at Draper U. He told me, one morning, that he and a group of classmates were out late drinking the night before. I asked if any of his classmates have hooked up. He said that nobody had, to his knowledge, which isn’t completely surprising, considering the dearth of females (seven women to 33 men).

“Pretty bad ratio, huh?” he said.

When it comes time to suit up for go-karting, I sidle up next to Scott Freschet. A scruffy-faced 28-year-old, Scott quit his job as a product manager at Yahoo a year ago out of restlessness and has since been living as a ski bum in Salt Lake City while his fiancée completes her residency. His family lives in San Mateo. His dad had heard about Draper U. and told Scott, who decided it might be the place to learn how to shed his worker-bee past and do something more individualistic. But since he arrived, he’s found himself immersed in an agenda of summer-camp games and “personal branding” workshops, in which even the most lowbrow elements are covered with a gloss of earnest grandeur. (Earlier that day, I watched Draper change the agenda line for a planned activity, a gathering of Draper U. students and his daughter’s college friends, from “mixer with sorority” to “hero-a-thon.”)

“The team-building stuff is really incredible and valuable for a chunk of the people,” Scott says. “But I think people with more experience have learned that elsewhere.”

The go-kart grand prix is about to start, and Scott, like everyone else, has squeezed himself into a onesie in preparation to zoom around the track. The competition will be extra fierce, because Draper announced earlier that everyone who finished ahead of Collete, the race-car driver, would earn a bonus point for their team. So, shelving his skepticism, Scott chooses his racing nickname, buckles up, and waits for the checkered flag.

Earlier that same day, I see Collete sitting in the school’s dining room, looking through old photos of herself in her racing uniform.

“I’m sending these to a V.C. who spoke here the other day,” she says. “He’s a driver, too.”

After three weeks, the mystique she felt on the first day, when Tim Draper tossed her his Tesla keys, hasn’t subsided. She’s been oohing and ahhing her way through lectures, bonding with her classmates, and eagerly trying to rack up activity-participation points for her team. Several weeks in, she Instagrammed a photo from a visit to Google’s headquarters. The caption read: “Helloooo@Google—Might as well be the #whitehouse.”

By now, Draper U. students have heard from dozens of entrepreneurs and investors, and most of them have gotten business ideas of their own. Collete is still hopeful that her start-up idea—an educational program to get more young girls studying science and math—will pan out. But most of her classmates have gone for-profit. Some are dreaming about secondhand-clothing exchanges, others are plotting food trucks, a few have signed up to work on a group-messaging platform called LivelyFeed that was started by a Draper student named Ryan. Others remain aimless but motivated.

“There are a couple of people here who, it’s like, I know you don’t have a company, but can I buy stock in you?,” Collete’s roommate, a cheery redhead named McKenna Walsh, tells me.

The two soon leave to join the other students gathered in the classroom. After reciting their daily oath, the class is treated to a presentation by a young French entrepreneur whose company sells a wireless locking device for corporate vehicle fleets. In a thick accent, the entrepreneur details all the yooge possibilities and eemportant innovations that will arise in the coming years, as technological solutions to the world’s transportation problems come to the fore. As an example, he talks about using sailboats as a carbon-free alternative to large shipping vessels.

After the French lecturer finishes, the students go upstairs to their dorm rooms. Collete and McKenna invite me in. Theirs is a fairly standard dorm room, though Collete has taken the liberty of swapping out the standard-issue bed linens for pink satin sheets. On the desk, beside straightening irons and laptops, sits a massive stack of books—the same stack every Draper U. student was given on the first day of school. Among the assigned readings are Donald Trump’s The Art of the Deal, The Wall Street MBA, and Ayn Rand’s The Fountainhead.

Perhaps because they’re being taught about the virtues of capitalism, most of the students now talk freely about money. I overhear discussions of Series A rounds, founder’s equity, and the process of finding angel investors. Increasingly, they’re thinking like businesspeople, rather than dreamers.

“A bunch of us have a bet among ourselves,” McKenna says. “The first one to make $100 million has to fly everyone else to Las Vegas for a party.”

Downstairs, Alex is dressed for the pool in Rainbow flip-flops and Oakleys with Croakies. He’s taking a dip before the next class session. I ask him what he’s taking away from Draper U. He shrugs.

“I don’t really know how it applies yet,” he says. “But it’s been great. Tim’s helping us accomplish our goals, and we’re helping him accomplish his.”

Alex tells me that the previous night, one Draper U. student brought his friend, a street hypnotist, to the dorm rooms for an impromptu performance in which he demonstrated his skills on a classmate.

“This girl put her shoulders on one chair and her feet on the other, like a plank,” he says. “The hypnotist told her to get stronger and stronger, and then he sat on her right in the middle. And it worked—she held him up.”

Hypnotism is a good metaphor for what’s happening at Draper U. Any experienced techie would tell you that there is often a gulf in Silicon Valley between the impossibly grand, world-changing ideas that tech entrepreneurs aspire to (“moonshots,” in industry parlance) and the reality of what gets funded. But moonshot talk serves an important function in the Valley’s ecosystem. By cloaking the mundane in the sublime, by making aspiring entrepreneurs feel that they, too, can change the world through an iPhone app, Draper is building up his students’ inner strength. And then, when, months or years later, a student’s start-up gets tested by a funding crunch or a critical mistake, he’ll think about his metaphorical superhero cape and bear the load.

“I want them to pick up the optimism of Silicon Valley,” Draper tells me one day while looking out over his students. That optimism isn’t empty puffery—in fact, in some respects, it’s the fuel that drives the tech economy. If there is some misdirection, then, in Draper’s superhero shtick, it’s probably the useful kind.

On graduation day, the superheroes assemble for the last time. It’s been a full eight weeks since they arrived, and the vibe in the room is reminiscent of the last day of summer camp. Students are exchanging phone numbers, signing each other’s commencement books, and promising to get back together for reunions in San Francisco.

“You came to this school as good, solid citizens, and you are leaving as superheroes,” Draper says. “Before, you may have been satisfied with the status quo. You may have been perfectly fine to get a job, have a family, live and die, avoiding trouble and not making waves. Now you are the waves.”

In lieu of diplomas, Draper U. students receive masks and capes printed with their superhero nicknames and are instructed to jump on each of a series of three small trampolines placed in a line in front of them. While bouncing from trampoline to trampoline, they’re told to shout, “Up, up, and away!” Then they assemble for a group photo.

“The world needs more heroes,” Draper says. “And it just got 40 more of them!”

After graduation, I walk to a nearby restaurant with Alex and several of his classmates. Alex orders a Stella and lets me in on the news that, in addition to the idea he pitched at session’s end for a restaurant-bill-splitting app, he and his classmates have decided to start another company. Their idea: a web business that allows people to post screenshots from their phones—of funny text exchanges, e-mails, and photo gags—and collects them all on a series of sites.

“There’s a market for screenshots,” Alex says. “Everybody takes them, but nobody’s really consolidated them all in one place.”

Alex and his friends went on a domain-name buying spree, snatching up names like nakedscreenshots.com and bullshitpix.com for use as possible spinoffs. They’ve already pledged to use any dollars they bring in not on Teslas or mansions but on trips to exotic locales together, where they’ll reunite and party.

Walking back to the school to collect my bag, I run into Scott tanning shirtless by the pool. He tells me that unlike many of his classmates, who are moving to the Bay Area in an attempt to continue their start-up quests, he’s planning to move to Seattle to be with his fiancée and possibly start interviewing for jobs at medium-size tech companies. “I don’t have to do a start-up to be happy,” he says. “But I don’t want to walk into a company like IBM, have them go, ‘Here’s your badge,’ and be bored there for the rest of my career. You want to have fun doing what you’re doing.”

A few weeks later, I talk to Collete. After the session let out, she flew to Florida, packed her bags, and drove right back to San Mateo. She’s living in the dorms again while working on a start-up idea and helping out at Draper U. She says Draper is opening a new building on the campus that will house space for both his son’s accelerator and start-up offices. He’s calling the building “Hero City.” Meanwhile, she’s raising a seed round of venture capital to start her own IndyCar company that will allow investors to buy the rights to a share of her future race winnings and sponsorship deals. She already has a lead investor, she says, and is hoping for more. I ask her if this means she’s given up on her dream of starting an educational program for girls. She says it hasn’t, but she needs to contend with her racing company first. “Once I close my round,” she says, “then I can focus on promoting my brand.”