Gentrification: New Yorkers can sense it immediately. It plumes out of Darling Coffee, on Broadway and 207th Street, and mingles with the live jazz coming from the Garden Café next door. Down the block, at Dichter Pharmacy, it’s visible on the shelf of Melissa & Doug toys. An algae bloom of affluence is spreading across the city, invading the turf of artists and ironworkers, forming new habitats for wealthy vegans.

It’s an ugly word, a term of outrage. Public Advocate Letitia James sounded the bugle against it in her inauguration speech on New Year’s Day: “We live in a gilded age of inequality where decrepit homeless shelters and housing developments stand in the neglected shadow of gleaming multimillion-dollar condos,” she cried, making it clear that she would love to fix up the first two and slam the brakes on the third. In this moral universe, gentrification is the social equivalent of secondhand smoke, drifting across class lines.

Yet gentrification can be either a toxin or a balm. There’s the fast-moving, invasive variety nourished by ever-rising prices per square foot; then there’s a more natural, humane kind that takes decades to mature and lives on a diet of optimism and local pride. It can be difficult to tell the two apart. “The things that low-income people think are nice are the same as what wealthy people want,” says Nancy Biberman, who runs the Women’s Housing and Economic Development Corporation in the Bronx. Communities fight for basic upgrades in quality of life, and when they’re successful, their food options and well-kept streets attract neighbors (and developers). It also works the other way: Richer, more entitled parents can lift up weak schools, says Biberman. “They’re more aggressive, and they empower other parents.”

Gentrification doesn’t need to be something that one group inflicts on another; often it’s the result of aspirations everybody shares. All over the city, a small army of the earnest toils away, patiently trying to sluice some of the elitist taint off neighborhoods as they grow richer. When you’re trying to make a poor neighborhood into a nicer place to live, the prospect of turning it into a racially and economically mixed area with thriving stores is not a threat but a fantasy. As the cost of basic city life keeps rising, it’s more important than ever to reclaim a form of urban improvement from its malignant offshoots. A nice neighborhood should be not a luxury but an urban right.

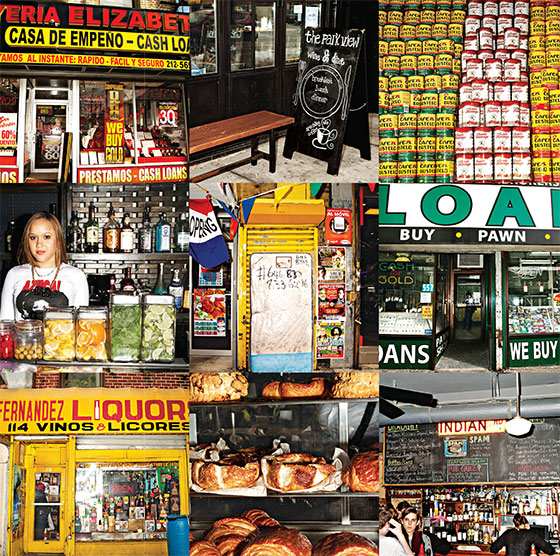

Somewhere, a mournful bugle sounds for every old shoe-repair place that shutters to make way for a gleaming cookie boutique. And yet some old-school businesses, if they’re flexible enough, can do more than survive: They can help nudge a neighborhood into the right kind of change.

“I’m a corner druggist,” says Manny Ramirez, the stocky, genial owner of Dichter Pharmacy. You can feel the pleasure he gets from pronouncing the phrase—the same retro jolt he gets from saying stickball, soda shop, and candy store. But he is hardly living in the past. He’s a canny businessman, Inwood-born and bilingual in English and Spanish, who has known some of his customers from his own childhood and keeps his antennae tuned to the tastes of those he hasn’t even met. Keenly conscious of his low-income neighborhood, he undersells the chain stores on basics like Tylenol and keeps the prices of most items at his lunch counter below $5. But he also stocks expensive lotions, organic moisturizers, and those Melissa & Doug toys. “Now we have people who will buy that stuff,” he says, sounding a little amused. “The idea of a new group of people with disposable income is excellent.”

The drugstore doubles as an ad hoc performance center, where Ramirez hosts chamber-music concerts, “Shakespeare Saturdays,” and poetry slams. “I’m big on social media, and I read the comments,” he says. “Among the people who have migrated here, there’s a large vegetarian and vegan group, so we have veggie chili on Wednesdays and Sundays. If you’re listening, however the neighborhood changes, that’s how you stay in business.”

Ramirez’s optimistic realism contrasts with a common perception of neighborhoods that remain unchanged for generations—at least until the gentrifiers roar in. A few areas where the change is that stark do exist, but far more typical are enclaves that each dominant ethnic group cedes to the next. Of course Inwood is changing; it always was. Right now, it’s a neighborhood of immigrants. Nearly half of its residents were born abroad, most in the Dominican Republic. Yet that “old Inwood” isn’t the one Ramirez grew up in. The year he was born, 1968, a TV station in Ireland aired a documentary, Goodbye to Glocamorra, which chronicled a neighborhood that could have passed for a city in County Mayo. “Five years ago, these apartment buildings were Irish to the last man, woman, and child,” the narrator says mournfully. “Today, their defenses have begun to crumble. The first Puerto Ricans have moved in. The first Negroes have moved in. And more will certainly follow.”

Ramirez was one of those Puerto Ricans, and he grew up acutely conscious of his bifurcated world. “I was too Spanish for the white community and too white for the Spanish community,” he recalls. When he was 10, his family moved from the mostly Hispanic east side of Broadway to the still whitish west side. In the early nineties, he moved to a New Jersey suburb. But Ramirez kept roots in the neighborhood, commuting to work for the district Rite Aid office and attending Good Shepherd. One day, he heard the checkout girls at a Dominican bakery grumbling in Spanish about how the neighborhood was changing. “I remembered when I was a kid and the white people were talking about the neighborhood changing—only they were speaking English.” Same complaint, different language.

Ramirez detected an opening. “I saw that there was an antiques store now, and a Moroccan restaurant, and I thought, This is something I need to jump on.” He bought the 100-year-old Dichter Pharmacy, where he had worked as a teenager. At times, it looked like a bad call. The recession hit the neighborhood hard. The Moroccan restaurant and the antiques store closed. In 2012, a fire destroyed the block. But Ramirez moved the business a few dozen yards up the street. Soon, the Badger Balm and apple-crumb muffins started to sell, and his poetry slams built a following—mostly from the west side of Broadway, though he’s trying to recruit some Dominican bards too.

With strong feelings about the past and an eye on the future, Ramirez is a one-man neighborhood-improvement center. He knows that the change he’s helping to nurture could one day turn on him, though he draws comfort from the fact that his lease won’t expire (so his rent can’t soar) for another twenty years. He keeps a fatherly eye on local kids and notes the low-margin stores that close and the new bars that force up rents. It pains him to see how few Latinos from the east side of Broadway welcome the new stores, and he knows that goodwill extends only so far. “If they’re a low-income family and they’re walking up the hill, past three or four other pharmacies, to buy Tylenol from me, are they going to go next door to Darling for a $4 cup of coffee? Probably not.” That doesn’t stop Ramirez from steering occasional customers there—until the day when he can feed their soy-latte cravings himself.

Nothing symbolizes the abyss between plenty and deprivation more than their physical proximity. The rapid gilding of Brooklyn has, in places, produced a grotesque companionship of vintage-clothing boutiques and Goodwill stores. Even as Bedford-Stuyvesant real estate approaches Manhattan prices, nearly a third of its residents—47 percent of its children—live below the poverty line. The neighborhood remains a bastion of unemployment, public assistance, and crime, moated by great ramparts of public housing. The old inner-city anxieties—that poor people who know only other poor people are more likely to remain that way—have not disappeared. Only now, instead of being stranded in sprawling ghettos, the poor are confined to islands of deprivation, encircled by oceans of prosperity.

Yet those Dickensian juxtapositions are actually a sign of a city that is doing something right. Subsidized housing helps preserve neighborhoods from a uniform wash of affluence. Chelsea and the Upper West Side—two of the wealthiest districts in the nation—still make room for low-income residents in nycha projects. “Those are neighborhoods where gentrification has been meaningfully tempered,” says Brooklyn city councilman Brad Lander, a staunchly progressive ally of Bill de Blasio’s. And all over the city, developers reap tax benefits by erecting luxury buildings and earmarking 20 percent of the apartments for renters who pay far less than their neighbors. A group of visiting developers from Mumbai was thunderstruck by that custom: They couldn’t imagine why well-off New Yorkers would voluntarily share their enclaves with the poor.

The fact that single-family townhouses and public housing often share the same few blocks gives community organizers a versatile set of tools. Colvin Grannum, the president of the Bedford-Stuyvesant Restoration Corporation, arrives at his offices the morning after the city has announced a $50,000 grant to help restore a small ice rink that’s been sitting idle for years near the corner of Fulton and Marcy Streets. He had been hoping for a more robust infusion; now he has to raise nine times as much as he’s getting. A staffer greets him with a shot of ambivalence: “Congratulations, I guess.”

Robert F. Kennedy’s children went skating on the Bed-Stuy rink in the seventies, when the area was an encyclopedia of urban decline. “It looked like a war zone,” Grannum says—“a desolate and blighted community.” In the summer of 1964, riots flared at the corner of Fulton Street and Nostrand Avenue, and mounted police shot at looters. Three years later, RFK and Senator Jacob Javits founded Restoration, the country’s first comprehensive community-development organization. Kennedy envisioned a fusion of public funds and private investment that would nurture local, self-reliant businesses: “What is given or granted can be taken away,” he said. “What you do for yourselves and for your children can never be taken away … We must combine the best of community action with the best of the private-enterprise system.”

That principle forms the foundation of nonprofit community-building groups all over the country and motivates private do-gooder developers like Jonathan Rose. “Can you create models of gentrification in which the benefits are spread out through the community?” Rose asks. The key, he says, is to make sure that residents and shopkeepers in low-income neighborhoods have equity and a political voice—before a real-estate surge. African-American residents of Bed-Stuy who managed to cling to their brownstones through the misery of the sixties, the heroin and crack years, and the devastating epidemic of foreclosures can finally reap the benefit that any longtime homeowner takes for granted: selling the house for a profit. “Development can be a positive force,” Rose says.

Today, Grannum has inherited the dream of healing through business. “I see our job as trying to create a healthy commercial corridor and capture as many retail dollars as we can,” he says. It’s not as if he’s got his eye on Tiffany and Per Se, but he would like the dollar stores and pawnbrokers to be joined by some slightly more genteel options. He mentions Island Salad, a Caribbean-themed place just across Fulton Street from his office, where $6.99 will buy an Asian Rasta (romaine, roasted teriyaki chicken, mandarin oranges, cucumbers, sliced almonds, crispy chow mein noodles, and “island sesame ginger”). It’s the sort of place a couple of young Park Slopers in search of an extra bedroom might wander into and think: Yes! I could live here.

Grannum is unapologetic about trying to bring a better life to Bed-Stuy’s poor by attracting the very outsiders who are supposedly making things worse. “We need affluent and middle-income people,” he insists. “We need a healthy community, and we need services that are first-rate. I just came from a meeting, and someone said, ‘Go to Seventh Avenue in Park Slope and recruit some of those stores!’ And I tell them: Businesses don’t bring affluence; they follow affluence.”

To the residents of East Harlem, a neighborhood ribbed with nycha towers and dotted with new condos, almost any change seems ominous. Andrew Padilla’s 2012 documentary El Barrio Tours: Gentrification in East Harlem ends with a group of conga players on a patch of sidewalk at Lexington Avenue and East 108th Street, with a tenement building on one corner and the DeWitt Clinton Houses on the other. Padilla’s film traces the creep of generic luxury and residents’ tenacious desire to hang on. The conga players’ impromptu jam session encapsulates both the history and the fragility of East Harlem’s identity: All it takes for it to vaporize is for the musicians to pick up their drums and walk away. And they have. According to the Center for Urban Research, Hispanics made up 52.9 percent of southeastern Harlem’s population in 2000; a decade later, that figure had fallen to 47.5. Whites took their place (11.5 percent before, 17.5 percent after).

But trend lines are not destiny. Who does the gentrifying, how, and how quickly—these variables separate an organically evolving neighborhood from one that is ruthlessly replaced. A trickle of impecunious artists hungry for space and light is one thing; a flood of lawyers with a hankering to renovate is quite another. The difference may be just a matter of time—but when it comes to gentrification, time is all.

Gus Rosado, a deceptively mild-mannered activist with a brush cut and a graying Clark Gable mustache, runs El Barrio’s Operation Fightback, which rehabs vacant buildings for affordable housing, and his latest undertaking is a huge gothic hulk at the far end of East 99th Street. Surrounded by public housing and the Metropolitan Hospital, it used to be P.S. 109, closed by the Department of Education in 1995 and badly decayed since then. After years of scrounging for some way to convert the school into living space, Rosado teamed up with the nationwide organization Artspace for a $52 million overhaul that will yield PS109 Artspace, 90 affordable live-work studios, half of them set aside for artists who live nearby. “The only way we were able to get this done was because of the arts,” Rosado recently said. “Suddenly, there was a whole other set of funding sources.”

Leveraging the moneyed art world to provide low-cost housing in a creative community seems like the perfect revitalization project. It promotes stability, fosters local culture, recycles unused real estate, and brings in philanthropic dollars rather than predatory investors. Artspace’s website makes the link between creativity and urban improvements plain: “Artists are good for communities. The arts create jobs and draw tourists and visitors. Arts activities make neighborhoods livelier, safer, and more attractive.”

At the same time, Rosado’s P.S. 109 project triggers a spray of explosive hypotheticals. Who should get preference: a white filmmaker from Yale who moved to East Harlem a few years ago and therefore qualifies as a resident, or a Dominican-born muralist who grew up in El Barrio but has since left for cheaper quarters in the South Bronx? Or: If East Harlem’s new Artspace incubates a nascent gallery scene, will its cash and snobbery help the neighborhood or ruin it? Will the Lexington Avenue conga players find a place in the neighborhood’s new arts hub?

Artists are like most people: They think gentrification is fine so long as it stops with them. They are pioneers, all-accepting enthusiasts, and they wish to change nothing about their new home turf (although a halfway decent tapas place would be nice). The next arrivals, though, will be numerous and crass. Interlopers will ruin everything. As artists migrate across the boroughs, from the East Village to Williamsburg, Red Hook, Bushwick, and Mott Haven, surfing a wave of rising rents, they are simultaneously victims and perpetrators of gentrification.

Rosado understands these dynamics well, but he believes that a little local involvement can go a long way toward shaping the subtleties of neighborhood change. “You can’t stop development and growth, but we’d like to have a say in how that transition takes place.” Lurking in that plain statement is the belief that gentrification happens not because a few developers or politicians foist it on an unwilling city but because it’s a medicine most people want to take. The trick is to minimize the harmful side effects.

In the popular imagination, gentrification and displacement are virtually synonymous, the input and output of a zero-sum game. One professional couple’s $2 million brownstone renovation in Bedford-Stuyvesant equals three families drifting toward Bayonne in search of barely adequate shelter. And so a sense of grievance and shame permeates virtually all discussions of neighborhood change. Even gentrifiers themselves are convinced they are doing something terrible. Young professionals whose moving trucks keep pulling up to curbs in Bushwick and Astoria carry with them trunkfuls of guilt.

The link between a neighborhood’s economic fortunes and the number of people being forced to move away, while anecdotally obvious, is difficult to document. Everyone’s heard stories of brutally coercive landlords forcing low-income tenants out of rent-controlled apartments in order to renovate them and triple the rent. But it’s difficult to know how often that takes place. Between 2009 and 2011, about 7 percent of New York households—around 200,000 of them—moved within the city in each year. Others left town altogether. Yet we know little about where they went, or why, or whether their decisions were made under duress.

Among experts, a furor continues to swirl over whether gentrification and displacement are conjoined. What qualifies as displacement, anyway? Forcible eviction by a rapacious landlord, obviously, but what about a rent that creeps up while a household’s income doesn’t? How about the intangible, dispiriting feeling of being out of place, or a young person’s knowledge that leaving the family home means living in another borough? Or the dislocation that comes when an industry flees, taking its jobs along? These pressures can affect investment bankers and nurses, as well as busboys and the unemployed, and it’s not always easy to distinguish coerced departure from a fresh opportunity, or gentrifiers from the displaced.

In 2005, Lance Freeman, a professor of urban planning at Columbia, examined national housing statistics to see whether low-income residents move more often once their neighborhoods start to gentrify. His conclusion was that they don’t. Mobility, he suggested, is a fact of American life, and he could find no evidence to suggest that gentrification intensifies it. Instead, it appears that many low-income renters stay put even as their rents go up. “It may be that households are choosing to stay in these neighborhoods because quality of life is improving: They’re more satisfied, but they’re dedicating a larger slice of their income to housing,” says Ingrid Gould Ellen, co-director of NYU’s Furman Center for Real Estate and Urban Policy. There is an exception: Poor homeowners who see the value of their properties skyrocket often do cash out. Freeman garnished his findings with caveats and qualifications, but his charged conclusion fueled an outbreak of headlines that have dogged him ever since.

Eight years after he lit the gentrification-is-good-for-everyone match, Freeman sits in his office at Columbia, more resigned than rah-rah about the implications of his work. He doesn’t doubt that displacement occurs, but he describes it as an inevitable consequence of capitalism. “If we are going to allow housing to be a market commodity, then we have to live with the downsides, even though we can blunt the negative effects to some extent. It’s pretty hard to get around that.”

That infuriates the British scholar Tom Slater, who sees Freeman’s data studies as largely irrelevant because, he has written, they “cannot capture the struggles low-income and working-class people endure to remain where they are.” Freeman waves away the binary rhetoric. “You can’t boil gentrification down to good-guy-versus-bad-guy. That makes a good morality play, but life is a lot messier than that.” In the days when RFK was helping to launch Restoration, an ideological split divided those who wrote cities off as unlivable relics from those who believed they must be saved. Today, a similar gulf separates those who fear an excess of prosperity from those who worry about the return of blight. Economic flows can be reversed with stunning speed: Gentrification can nudge a neighborhood up the slope; decline can roll it off a cliff. Somewhere along that trajectory of change is a sweet spot, a mixed and humming street that is not quite settled or sanitized, where Old Guard and new arrivals coexist in equilibrium. The game is to make it last.