“No dictatorships,” Abdullah Alsaidi said firmly the other day. “That was the policy.”

You’d have been forgiven for thinking he was holding forth on his treatment of various despots throughout the Arab world. Alsaidi, who resigned last month as Yemen’s ambassador to the United Nations, was so horrified by the strong-arm turn taken of late by the Yemeni government—ignoring a populist groundswell for political reform, deploying security forces to shoot massing protesters—that he abruptly broke ranks with the president whose administration he had served since 1984.

At the moment, though, just two weeks later, Alsaidi was talking about his thoroughly democratic approach to home décor, with a certain amount of wistfulness. In 2005, he and his family finally moved into the majestic limestone townhouse on 71st and Park (five bedrooms; eight fireplaces, two of brecciated peach marble; a narrow sixteen feet across, “but the depth is what makes this house”), after he convinced the Yemeni foreign ministry that there was value in laying down nearly $7 million so that its U.N. representative would have a New York dwelling fit for an ambassador. The Alsaidis’ search for it had lasted through his first three years on the job at the U.N., during which time they endured a Trump rental on First Avenue. He declared in no uncertain terms that in their new home, each vote would count equally. “Everyone got to choose how to do their own room,” he recalled. “I said, ‘There are no dictatorships here,’ and my wife and children selected what they desired.”

So his three children, all adults now, chose among loft beds, desks, and reading chairs from Ethan Allen for their rooms, and his wife, Amirah, went to work on swags and jabots. Alsaidi, meanwhile, made a personal fiefdom of lighting, installing five crystal chandeliers that burst from the ceilings like fireworks and descend with the languid curves of an odalisque in pantaloons. “I found them in the Czech Republic,” he said. “I mean, come on, where do you think you get Bohemian-crystal chandeliers like that? These are things you know if you’re a diplomat. Actually, I found them in catalogues, then I had the Yemeni ambassador there purchase them tax-free.”

All that, and much more besides, he gave up when he stepped down. Now he was untethered from his homeland, adrift in New York City. It was something to think about, though he knew his problems didn’t compare to those of his countrymen. “These are not real problems I have,” he said. “This is nothing.”

All the death, all the protests, and still President Ali Abdullah Saleh refuses to step down. Yemen has not always been peaceful—there was a civil war in 1994—“but it never happened that you go and bring snipers and start shooting your own, unarmed people.”

The evening the first casualties were reported, Friday, March 18, Alsaidi returned home from the U.N. and discussed quitting with his family. “My wife, Amirah, she understood and she agreed,” he said. “My youngest daughter had been telling me to leave for a long time. She’s naïve.” The next morning, he went to the empty offices of the Yemeni Mission and tendered his resignation to the president by fax. “I had a young man on the staff come in to assist me. I don’t type in Arabic.”

Then it was good-bye, townhouse, and farewell also to the household staff, car and driver (“I never took taxis”), and gravy-train meal plan. “I knew literally every restaurant in this town,” he said. “It’s part of the job. You invite people to lunch, or they invite you. For Northern Italian, I think Felidia is the best. For Southern, I can’t say; there are so many places.” He smiled gamely. “Now I’ll buy a tuna sandwich.”

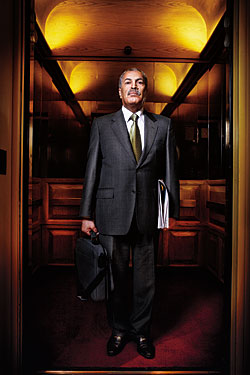

Alsaidi has a compact frame and a graying mustache. In his living room on a recent evening, he wore a dark-brown suit and caramel-colored, high-vamped loafers. He excused himself to fetch coffee, then headed down the stairway again and returned empty-handed. “Some nuts, then I’ll be back,” he said, on his way now to an upper floor. “I just need to find them.”

He came back with Yemeni almonds and raisins and sat down again. “We will be fine,” he said. He will still be able to do the things he most loves to do in New York: play soccer in Central Park with his son, browse the bookstores at Columbia and NYU for obscure medieval-history works.

“And we’ll find an apartment,” he said. He rolled his eyes. “On the West Side.”

As he began to look for a new place to live, Alsaidi was discouraged by two things, “the lack of space and the prices,” he said. “Maintenance alone in a co-op will end up costing $7,000 a month—I didn’t spend that much of my own money in a year here.”

Alsaidi is not alone in his dispossession. The rebellions throughout the Middle East and North Africa the last couple of months have put a considerable contingent of diplomats in America into varying degrees of limbo. The Libyans, whose unresolved government chaos is the most pressing to the State Department, are the greatest in number. On February 25, three days after stating his reluctant allegiance to Muammar Qaddafi (“I am not one of those who would kiss his hands and feet in the daytime and denounce him at night”), Libya’s ambassador to the U.N., Abdurrahman Mohamed Shalgham, broke from his administration in a tearful speech to the U.N. Security Council and was embraced by his deputy Ibrahim Dabbashi, who had resigned earlier in the week and accused the Libyan leader of committing genocide against his own people. The remaining staff of the Libyan Mission—some twenty younger charges d’affaires, ministry counselors, and third secretaries—followed suit.

Even though the Libyans do not represent the government in power in their country, they have continued to report to work at the U.N. “You cannot say they are in limbo,” said Aly R. Abuzaakouk, a Libyan human-rights activist in Washington who is a longtime friend of Dabbashi’s. “They have officially agreed to represent the Transitional National Council”—a loosely knit association of pro-Democratic factions that will control Libya following Qaddafi’s hoped-for ouster.

Some view the Libyans’ decision skeptically. “Both of them have long ties to Qaddafi—they were trusted diplomats in sensitive posts,” said Fred Abrahams of Human Rights Watch. “Shalgham was in charge of Libya’s foreign ministry for years. It’s difficult to look at these decisions as anything other than opportunistic. But we certainly applaud the result.”

Qaddafi’s attempts to appoint other men to fill their positions representing Libya at the U.N., meanwhile, have had an element of farce about them. His first selection, Ali Abdussalam Treki, was reportedly unable to obtain a visa to enter the U.S. His second choice, Miguel D’Escoto Brockmann, is not from Libya but Nicaragua, and his nomination mostly just served to remind the Western world of the two countries’ alliance in the eighties; at any rate, he didn’t take the job.

“We will be fine,” said the former ambassador. “We will find an apartment”—he rolled his eyes— “on the West Side.”

Alsaidi’s resignation may be more complex. While the Libyans here are united—the country’s ambassador to the U.S., in Washington, also resigned—Yemen’s lot is divided. Dozens of cabinet ministers and diplomats—including Yemeni ambassadors to Canada, Germany, China, Saudi Arabia, Egypt, and Iraq—have decided to support the protest movement. But the ambassador to the United States, Abdulwahab Abdulla Al-Hajjri (a brother-in-law of President Saleh), has remained in office, as have the staff of nine that worked under Alsaidi at the U.N. Alsaidi told his people to stay put. “Some of them wanted to do something, but I wouldn’t let them,” Alsaidi said. “These are young diplomats. They would be out on the street.”

The members of the Libyan Mission, on the other hand, had reason to feel much freer to take a stand against Qaddafi. “They are rich, and Qaddafi is persona non grata here,” Alsaidi said. “Even if they lose their jobs, the State Department will look after them. They have $34 billion in frozen assets here. Yemen has nothing here. I don’t even know if I will get my last salary check sent to me.”

The truth is that even before his defection, Alsaidi was something of a world citizen, mentally stateless even as he was tied to Yemen. He finds the Middle East “too suffused with politics.” His career path could been seen as a series of efforts to set himself apart from the image he holds of many peers from Middle Eastern countries—whose worldviews he sometimes thinks can be plagued by a strain of zero-sum self-interest. Yemen is one of the most impoverished nations on Earth, though Alsaidi grew up in a wealthy household. “We are a known family in both Sana’a and Aden,” he said. “We are good in business, good in trade. Though to be wealthy in Yemen is not to be so wealthy that a job at the Ford plant in Dearborn, Michigan, isn’t preferable.” That was what his father left home to do when Alsaidi was a child, mailing money to his family in Yemen every few months but returning to see them only every couple of years.

In 1968, Alsaidi came to Brooklyn, and later attended Long Island University, eventually becoming a U.S. citizen. He studied political science and got involved in student government. “I was the student representative on the selection committee for a new dean when they ended up hiring a woman,” he said. “I learned afterward that she had been worried because of the view that Arabs were hostile to women.”

He decided to pursue a master’s degree in philosophy at Columbia—a favorite professor was Arthur Danto, the art critic and philosopher. His graduate studies further disappointed his father, who hadn’t wanted him to go to college at all. He had expected Alsaidi to join him and the Yemeni community in Dearborn (there are an estimated 10,000 immigrants from Yemen there). “But Detroit is not a city where you talk about a critique of Kant,” Alsaidi said. “People there are consumed with money. Rich or not so rich, it’s how much does your job pay you, how much is that house, how’s business?”

As he rose through the Yemeni foreign service, which he joined in 1984 (he had returned home two years earlier to work for USAID), there was more chafing against socioethnic type. “Most of the people who come to this job are interested in gaining power by getting into the field of finance,” he said. “I wasn’t. They thought I was dumb.” He was posted in Berlin at the time the Wall fell.

Alsaidi was in the U.S. when Iraq invaded Kuwait. “There was this infatuation with Saddam in parts of the Arab world, especially those who resented Kuwait and their wealth,” Alsaidi explained, adding that he’d gone out of his way to let a deputy in the Yemeni foreign ministry know that their country was betting on the wrong horse. “I told him, ‘Realistically, this guy cannot impose his will on the international community, not when you have a match between a superpower and a mediocre Middle Eastern military. He has to retreat.’ I knew that from my reading of Foreign Affairs.”

Saddam Hussein was a mentor to Saleh, who was known among Yemenis as “Little Saddam,” but Alsaidi insists it was only recently that his longtime boss—Saleh has been president of Yemen for nearly 33 years—became incapable of brooking dissent. “He used to call me at night to ask my opinion, and when I disagreed with him”—about Iraq and Kuwait—“he said, ‘You know what? I think you are right.’ Around 2005, that sort of thing stopped. Last year, when I wrote in a report to him that the U.N. was thinking of contingency plans in Yemen in the case of an uprising, the administration phoned me five times to say, ‘The president is not happy with your report, because it isn’t true.’ ”

There’s a lightness to Alsaidi’s life that was absent a month ago. He has already started a new job, at the International Peace Institute, a think tank where he had occasionally participated in panel discussions. “They are making me a senior analyst,” he said. “The money is better than an ambassador’s salary. We have some savings. What do you save for in life if not a time like this?”

Now his nation is New York City—even if he’s not going to live in one of its finer residences. It’s a citizenship he’s been moving toward for a while. “It’s not only the moral issue,” he said candidly. “It’s the way my colleagues at the United Nations would look at me. I believe people there think highly of me. Ban Ki-moon, the secretary-general, told our foreign minister that I am his adviser. So after witnessing the president authorizing the killing of our people, to remain in his administration and try and rationalize it? Well, it would not look seemly. I would rather take the subway.”