At Indian Point Energy Center, the 49-year-old nuclear-power plant 25 miles north of New York City, they talk a lot about safety—safety with regard to terrorism, to floods, to power outages and meteorological events. Most of the talk revolves around keeping the reactors cooled, and protecting what’s known as the spent-fuel pool. This is important, because it takes a few thousand years for radioactivity to decay to a point where it is no longer hazardous. When I show up on a recent weekday, guards with semi-automatic weapons greet me at the top of the hill overlooking the plant, and after a background check, I pass through a recently constructed concrete barrier that Joe Pollock, site vice-president of Indian Point, refers to as his Great Wall of China.

Pollock is responsible for the overall operation of Reactor Units 2 and 3, as well as the maintenance of Unit 1, which was shut down in 1974. (According to a recent Nuclear Regulatory Commission report, low levels of strontium-90 and tritium “appear to be leaking” from Unit 1’s spent-fuel building.) Pollock has worked at nuclear-power plants for over 30 years and comes across as a good-natured guy who absolutely means what he says. He has spent a lot of time this year defending nuclear power. In addition to the tsunami in Fukushima, there was the large East Coast earthquake that shook a nuclear-power plant in Virginia, as well as the tenth anniversary of September 11 (the terrorists had reportedly discussed Indian Point as a potential target). Pollock lives with his wife a few minutes’ drive from the plant, and at the barbecues and around town this summer he frequently found himself discussing disaster preparedness. “You talk to a commercial-airline pilot, they’ll say it’s almost impossible to spot us,” he tells me. The level of structural malfunction at the Fukushima plant, he explains, would not happen here. “They had a radiological release where all three barriers were defeated.”

As Pollock sends me into the plant, I am introduced to a team of friendly nuclear-power-plant workers who know well that the current governor of New York wants to shut them down. “There are a lot of people who don’t like us right now,” says Robert Cranker, a senior technician. “But they don’t understand nuclear power. I don’t blame them. I always tell people that it’s like if I learned everything I know about fire from the Great Chicago Fire, then I would be scared. With nuclear, people know everything they know from Hiroshima and Nagasaki.”

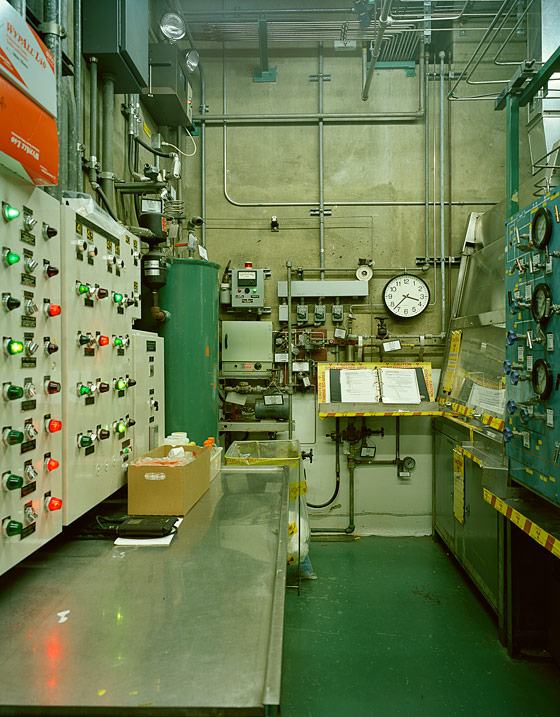

I am security-checked through way stations and I.D.-swiped through doors. Soon we pass a bulletproof-glass window that offers a view of one plant’s control room, which resembles the set of a boring 1979 industrial film: crisp analog dials, a roomy-submarine feel. Now wearing earplugs and hard hats, we pass the giant, bone-rumblingly loud turbines that date from the Carter administration. Next door, 547-degree heat from the reactor’s core is heating water to make steam that turns the generator that produces electrons that shoot down transmission cables and underground substations and through the street and into your outlet that slips them into the lithium-ion battery that powers your iPhone. The number of electrons firing out—2,000 megawatts, enough to power 2 million homes—brings the plant great respect among the power-planners in New York State.

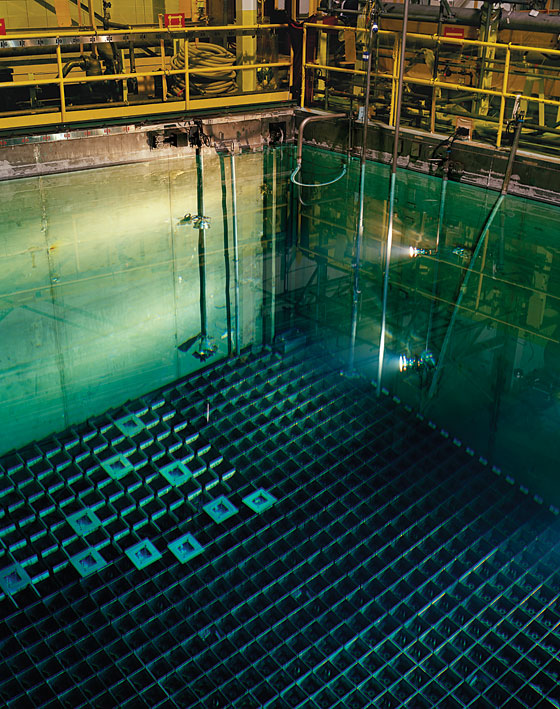

Finally, after sitting down with a radiation-safety technician to discuss the amount of radiation one might safely be exposed to—in this particular case, .2 millirems per hour—I am permitted to view the spent-fuel container, the 23-foot deep, glowing pool containing several decades’ worth of used uranium (the glow is just from the lights used for the monitoring cameras). Visitors are cautioned not to stand directly over the pool, to limit exposure. And so for about five minutes I stand in the eerie generator-muffled calm of the square, concrete room, mesmerized, until my personal radiation detector ticks up to .2, at which point I carefully retrace my steps out the building, passing knobs and valves, mindful of Mrs. O’Leary’s cow accidentally kicking the lamp.

It often takes a disaster, or the threat of one, anyway, to get people thinking about their power—otherwise they just plug in or charge it overnight, without giving a second thought to where those electrons are born. The last time New Yorkers were focused on Indian Point was in the fear-drenched aftermath of September 11. (You may recall Rudy Giuliani, in some of his first work at Giuliani Partners, vouching for Indian Point’s security with his then-associate Bernie Kerik.) Well, Giuliani’s back—starring in new advertisements, paid for by Entergy, the Louisiana-based company that owns Indian Point, in which he stands before a green screen and accentuates the energy needs of “the greatest city on Earth.” “You have the right to know the facts about this important source of electricity,” he tells us. “All of us have a right to know why Indian Point is right for New York.”

In the 2011 version of our energy conversation, however, possible meltdown at Indian Point is not the only subject terrifying New Yorkers. The recent discovery of natural gas beneath the Marcellus Shale formation upstate has led to a boom in the mining procedure commonly known as fracking, which exhumes gas by pumping chemically treated water into the ground, and a corresponding boom in outrage, as many New Yorkers fear our watersheds will be despoiled in the process. Add to that the slow-moving disaster movie of climate change, which left-of-center New Yorkers feel obliged to tackle, though they aren’t exactly sure how. Then there is the fear—this one powered by the Entergy folks in particular—that we will rashly choose to close Indian Point, only for the city to wind up power-parched, blacked out and sweating during global-warming-enhanced summer heat waves that spark a return to the urban looting of the seventies. At least for the moment, energy policy in America comes down to which terrible outcomes we choose to tolerate over others. Here in New York, though the conversation tends to be astonishingly mind-numbing in the fine print, it is, on the macro level, unusually emotional: The decision of how we choose to power ourselves over the next half-century seems to hinge, to a surprising degree, on who can make the most compelling case that every other option is unacceptably frightening.

Andrew Cuomo has been trying to shut Indian Point for over a decade. In 2001, he signed on with a petition from Riverkeeper, the Hudson River environmental group, to close the plant. He campaigned against it when he ran for governor in 2002 and joined a suit against it as attorney general. But now comes his best chance to fulfill a longtime promise, with a hearing to renew Indian Point’s operating license set to take place next year. If the two reactors’ initial licenses are not renewed, then they must shut down in 2013 and 2015 (or soon thereafter). They require a federal permit, but the State Department of Environmental Conservation has to sign off, and Cuomo’s argument has always been, as he put it in his blog last month, “the reward doesn’t justify the risk.”

What precisely is the risk? Difficult to calculate. When Pollock plans for disasters at Indian Point, he talks about something called Beyond Design Basis Events. This includes Hostile Action-Based Events (e.g., terrorists) and SAMGs, a nuclear-industry acronym for Severe Accident Management Guidelines. “It doesn’t matter what event—say, a meteorite from the sky—it keeps you on your priorities,” he says.

Let’s suppose a Beyond Design Basis Event occurs in the shape of an earthquake larger than one Indian Point was built to withstand. As far as scenarios go, this is not science fiction. Plate tectonics was only a theory when Indian Point was being planned. Likewise, we now have a better picture of the patchwork of faults called the Ramapo Seismic Zone, which fans from eastern Pennsylvania to the Hudson Valley. A 2008 report by Columbia University’s Lamont-Doherty Earth Observatory shows that large quakes of magnitude 5 have happened in the past—there have been at least 3 since 1677 in the Greater New York area—and that larger quakes should no longer be considered impossible or even unlikely. The magnitude-5.8 quake in Virginia hit in the vicinity of the North Anna nuclear plant with twice the amount of ground movement the structure was designed for, cracking a wall of a reactor’s containment unit and shifting the concrete pads under casks that store used nuclear fuel. It was the first time an operating U.S. nuclear plant experienced a tremor that exceeded its design parameters. (The plant is awaiting reopening.)

Say we experience a magnitude-7 quake in the area—something that the Columbia report says has a 1.5 percent chance of occurring in any 50-year period. According to Lynn Sykes, an author of the report, Indian Point was designed to withstand a quake of 5.3 at a distance of 35 miles. We now know it sits on a previously unidentified intersection of active seismic zones. A 7 on a fault a few miles away would involve dozens of times more force than the reactors could theoretically handle. Entergy estimates that Indian Point was built with more seismic capability than documented, and many nuclear-power experts agree. “We’re built on bedrock,” Pollock points out. But even if you give Indian Point the benefit of the doubt, and the core reactors survive a hit, a safety official inventing a severe-event scenario might plausibly imagine the failure of a few of the pipes running through the reactor—a hydrogen pipe essential for cooling the core, for instance, or a line carrying lubricating fluids. These kinds of breaks have happened before, and they often lead to fire, according to David Lochbaum, the director of the Union of Concerned Scientists’ Nuclear Safety Project.

If there was a fire in the reactor, then Indian Point would, by regulation, begin to shut down. Fortunately, if the sprinkler system was damaged in the quake, then workers could turn to the additional fire equipment and backup generators installed after 9/11. Unfortunately, the scenario that involves enough shaking to damage the reactor building also involves damage to the buildings containing the emergency fire equipment. Indian Point would then call in local fire officials, who, Entergy boasts, are well prepared to deal with radiation releases. But suppose this quake has damaged area transportation routes. Suppose trees and wires are down and the plant is running on backup power. Suppose emergency officials are dealing with other buildings that have collapsed on emergency equipment: A 2001 study argued that a magnitude-7 quake in nearby Bergen County would destroy 14,000 buildings and damage 180,000. In this scenario, the fire spreads and the reactor is no longer under control.

The core begins to heat up. Perhaps technicians would fashion another cooling system—theoretically, they could call on the Hudson River to flood the reactor. But if that fails, it would be a matter of hours before the ceramic pellets of uranium evaporate the water meant to cool them. This melted pile of pellets would quickly become a molten blob, heating up toward 5,000 degrees and melting through the floor of the reactor. Then hydrogen would build up, which would cause an explosion. In Fukushima, pieces of fuel were found over a mile away; imagine a geyser hurling radioactive material to Peekskill at 1,000 miles an hour.

As far as releases of radiation go, the NRC mandates only a ten-mile evacuation area for Indian Point. In other words, official policy states that New York City would be spared any sizable risk from a meltdown. But perhaps it’s more sensible to look at what the NRC had to say in Japan. After the Fukushima meltdown, the NRC told Americans living there to clear out of a 50-mile zone. Subsequently, the Japanese government declared huge swathes of land uninhabitable for decades. The local 50-mile equivalent is a circle defined by Kingston to the north; Bridgeport, Connecticut, to the east; the Delaware Water Gap to the west; and the southern tip of Staten Island to the south. It includes all of the 8.2 million people living in New York City.

If you agree with the governor that this small risk of contamination of 2.7 percent of the U.S. population is not worth the benefit of nuclear power, then you have to come up with some other way to replace the 2,000 megawatts of energy Indian Point currently provides to New York City and Westchester. And this is where other fears start to come into play. The disaster scenario preferred by the pro–Indian Pointers began showing up this summer in large brochures mailed around the city: In a dark room, a child studies by candlelight as a mother prepares dinner wearing a headlamp. It is a depiction of a cavelike city, where blackouts are a way of life, where (as shown inside) Times Square is dark. “Take nuclear power out of New York’s energy mix and we could be left in the dark again,” the brochure says.

The brochure was paid for by a group called the New York Affordable Reliable Electricity Alliance (AREA), which reportedly receives funding from Entergy, and the mailings are just the start of a nuclear-friendly multimedia public-relations campaign. (A recent post on Indian Point’s Facebook page: “Have you seen the Indian Point Energy Center YouTube channel? Which video is your favorite?”) And it is not just Entergy that supports Indian Point. For the most part, the closer you get to people who have political or transactional interactions with a public that risks losing power, the greater the concern about keeping the lights on. Con Edison, which completed the sale of Indian Point to Entergy days before September 11, 2001, is keeping a low profile on the issue. “We’re trying not to take sides,” says Joseph Oates, a vice-president at the company. Oates has, however, testified to the State DEC that a closed Indian Point could mean loss of power, and he speaks in drastic terms. “We will not have enough energy for everybody, and electricity will be rationed,” he testified. “The first calls will come to us: ‘How come I don’t have electricity?’ ”

Likewise, Mayor Bloomberg, whose extension on his own term limit ends a few months after the license for reactor No. 2 expires, has called Indian Point “critical.” City Hall estimates that an Indian Point shutdown would lead to a 5 to 10 percent rise in Con Ed bills. And if you talk to anybody who works with the energy grid, he will inevitably get around to that blistering day last July when the city took its biggest ever power draught—13,166 megawatts, a figure that makes city officials understandably jittery. “If you close it,” asks Deputy Mayor Cas Holloway, “what’s in its place?”

Entergy and its allies insist it will be impossible to find enough replacement power anytime soon—or certainly by 2012. “New York State is at a crossroads for its energy future,” says Jerry Kremer, a former state senator who is chairman of AREA. “The agenda for new power has been driven by the anti-nuclear people who want nothing.” At the moment, lots of organizations are presenting their plans for how to replace the 2,000 megawatts, from power companies that want a piece of the replacement action to nonprofits like Riverkeeper and the Natural Resources Defense Council, which issued a joint report last month showing that Indian Point could go without renewal and that the lights in New York would stay on (as they do, albeit temporarily, each time Indian Point powers down one of its reactors for maintenance). Tom Congdon, the governor’s secretary for energy policy, says that just among the various plants in development, there is “more than enough projected power that could more than replace Indian Point within the time period.” But the governor’s office was recently contradicted by a report commissioned by Bloomberg predicting that closing Indian Point would result in city power outages. A recent Post editorial called Cuomo “enviro-zany” and ridiculed his assurance that we could find alternative sources of power elsewhere. “From where exactly, governor?” it asked.

A couple of weeks ago, at a packed school auditorium in Greenwich Village, a skeleton wearing a black robe emblazoned with the word die is walking through the aisles as a crowd speaks out against the natural-gas pipeline proposed to run under the West Village. “I am a resident of the neighborhood,” one woman says, taking her turn to testify. “I live in the blast radius.”

It is a public meeting organized by the Federal Energy Regulatory Commission on the $850 million pipeline planned by Houston-based Spectra Energy—fifteen miles of new pipeline connecting freight trains in Jersey City to the city’s natural-gas grid in Staten Island and the Village. Speaker after speaker cites previous pipeline explosions around the country, and chides the federal regulatory agency in charge of pipeline safety. “How will you bring back our dead?” one resident asks. Others lay out a scenario in which gas extracted from upstate fracking would be delivered to New York City and then on to global natural-gas markets, making the U.S. “the Saudi Arabia of natural gas.” At which point a speaker asks: “Do the people in Saudi Arabia seem happy right now?” Actor Mark Ruffalo takes the microphone to berate the federal representatives, bringing the crowd to long cheers as he accuses them of “mainlining” New York State to the ecological disaster that he has seen in Pennsylvania. “This is purely about profit motives,” he says. “Go to your heart and ask yourself, ‘Is this right?’ ”

Another disaster scenario: Child studies by candlelight, mother cooks wearing headlamp.

When an aide to Borough President Scott Stringer reads an abridged statement saying he could not support the pipeline “as it is currently planned,” the crowd erupts again. The aide goes on to say Stringer is opposed to the pipeline transporting any natural gas mined through upstate fracking, which he describes as ruinous to upstate communities and “environmental pillage.” Stringer, though, is not opposed to all natural gas. Natural gas, his aide says to a now-subdued crowd, is expected to replace the dirty heating oil in apartment-building boilers. In the complete version of the statement handed out later, Stringer calls Indian Point “the elephant in the room.”

The question of whether to close Indian Point is not necessarily related to the discussion of whether to allow fracking upstate. After all, the natural gas New York City currently consumes is mostly imported from Canada and Mexico, and the natural gas discovered upstate could presumably sell on a global market. But the two energy conversations could, at the very least, be perceived to be related, which is enough to become a political liability for opponents of Indian Point. Even among environmentalists, you find tensions between those who prioritize closing Indian Point and those rallying against fracking. “How the state works its decisions about where its energy comes from is all incredibly connected to the fracking issue,” argues Katherine Nadeau, water and natural-resources program director for Environmental Advocates of New York. Some conservationists even worry that Cuomo will risk fracking gas as some kind of Indian Point trade-off.

Albany insists there is no fracking–Indian Point connection. “We are not linking them,” Congdon says. “We’re only getting about 5 percent [of our energy from in-state natural gas] right now. It’s not something we are pursuing purely from the standpoint of replacing Indian Point.” Cuomo has called the state’s watersheds “sacrosanct” and has promised strict environmental regulations on whatever fracking is conducted in the future. Still, it’s hard to know precisely what he means when he calls watersheds “sacrosanct”—everywhere is somebody’s watershed, and New York City’s watershed has already been placed off-limits for fear of chemicals’ leaking into the water supply.

As for Spectra’s proposed pipeline, opponents point to the contract the company has signed with Chesapeake Energy, which was recently fined $900,000 for contaminating water supplies in Pennsylvania. They note that there would be nothing stopping Spectra from importing fracked gas from upstate, either. The mayor has spoken out strongly for the project, telling reporters last week that it is “a gas line we desperately need.” He also took the opportunity to make a larger point. “There’s no free lunch,” he said. “You’re gonna have choices. You want more nuclear? Do you want more coal? Do you want more natural gas?” Or as Entergy helpfully tweeted last month: “Yes, there may be alternative sources of power—but at what cost to our economy & environment?

Entergy poses a good question: If you are against the possible destruction of New York City by Indian Point, and also against the as-yet-unquantifiable possibility of watershed damage caused by fracking, and at the same time against summer blackouts and all their attendant public-health and safety issues, is there anything left to be for?

As it happens, there is something exciting about the possibility of closing Indian Point: It could serve as a system-altering shock to New York’s energy portfolio. Even people who are concerned about shutting down the plant see this as a chance to rethink how to power the metropolitan area.

For 75 years after Thomas Edison built the first power plant and distribution line in lower Manhattan, city power was distributed locally through a patchwork of lines. Then Robert Moses built enormous hydropower projects on the Canadian border and large transmission thruways straight down the state. This vastly improved the city’s power capacity, but those transmission lines haven’t been expanded in over a decade, and so even as more low-impact power is generated upstate and in Canada, only a limited amount can make it through the terrible energy traffic jam in the lines between Albany and Westchester. This is partly what has made Indian Point so attractive to power planners: It adds a big jolt of electricity exactly where lines clog up the worst.

“Closing Indian Point is a no-brainer,” says Paul Gallay, Riverkeeper’s president. The Riverkeeper-NRDC report outlines ways to bypass the nuclear plant with what would essentially be extension cords: huge new energy cables that could draw thousands of megawatts from Canada and northern New York to the city. Something similar is expected to be highlighted in another report due in January from the New York Independent Systems Operator, or NYISO, the nonprofit in charge of the state power grid’s operation (it is the FAA of electrons). One idea on the drawing board, the Champlain Hudson Power Express, is a 330-mile cable running from Quebec to Queens, estimated to cost $1.9 billion. Another, the West Point Transmission project, is a 100-mile cable from Albany, estimated at $900 million. Both of these cables would travel mostly underwater, which would reduce nimby concerns about where to site the power lines. A simpler but less ambitious option is to add more capacity to the existing power lines running through the middle of the state. Cuomo has yet to champion any cables specifically, but they are likely to play a role in whatever energy portfolio he proposes.

Any improvement to the state’s transmission lines would, according to Congdon, reduce electric bills. It would also be a de facto plus for the environment and public health. That’s not just because faraway power plants affect fewer people than power plants located in cities. It’s also because, at least for now, renewable energy like wind power is easier to produce up north, where wind is more constant and land is cheaper. (The West Point Transmission line, for instance, is tied in part to wind power in the Finger Lakes and Great Lakes regions.) And opening a huge market like New York City to upstate wind and solar might encourage the kind of investment that could bring down costs.

If Indian Point is closed and transmission-line improvements aren’t enough to fill the gap, New York City would have to rely more on power made within city limits. This, in the short term, could be environmentally disadvantageous. Some of our local power plants rely on kerosene, a particularly dirty fuel, and running them more frequently would lead to increased carbon emissions. However, without Indian Point, New York City would have a stronger incentive to upgrade these plants to run more efficiently. Out in Astoria, for instance, there is a “peaker plant” whose 32 retired jet engines currently burn kerosene and natural gas a total of 800 cycles a year. A plan is in the works to convert the engines to an energy-efficient combined-cycle plant, which would boost the plant’s output from 600 megawatts to 1,040 megawatts and drop emissions by 90 percent on peak days. Renovating just this plant alone would reduce significant emissions in the entire city by 16 percent.

And then there’s the obvious if counterintuitive idea that the cheapest way to make power is to not use it. Politicians and executives of all stripes are becoming more bullish on energy-conservation measures, which Kevin Lanahan, Con Ed’s director of governmental relations, calls “the low-hanging fruit.” To put Indian Point’s 2,000-megawatt output in some perspective: During the summer, New Yorkers use approximately 6.1 million window-unit air conditioners (about one fifth the national total) that together draw 2,500 megawatts of power. This past summer, Con Ed initiated “demand response” programs that gave payments to customers who agreed to cut back their power consumption during peak periods. For those four scorching days in July, the program cut down peak demand by approximately 500 megawatts. Similar conservation measures are taking place within buildings, too. The Empire State Building, after an energy retrofit, is advertising itself as something along the lines of a Biosphere 3, with efficiencies and renewables galore; it has powered down energy consumption by 38 percent.

The future of New York City’s power grid, as sketched by environmentalists and building managers alike, has a lot to do with programs like demand response, which doesn’t cost anything and saves everyone money. But there are a lot of other, more experimental projects in the works: industrial-grade solar panels that might blanket city landfills; wind turbines at Fresh Kills park; tidal-power experiments under the Verrazano-Narrows. It’s not impossible to imagine New York eventually powering itself cleanly through the life of its estuary, the tides and the winds, with power moving from your rooftop down to neighborhood underground batteries.

But at the moment, everything appears to be in limbo, as various private companies wait for the state to make its move. “This is really uncharted territory,” says Richard T. Anderson, president of the New York Building Congress. “We need a call to action. Is this governor going to be an activist governor in terms of power?” Part of the problem is that Andrew Cuomo doesn’t have nearly the same ability to get things done than his father had. Two decades ago, if the city were facing a power shortage, the state would have asked a public utility like Con Ed to build a plant. But when the industry deregulated, Con Ed got out of the business of building its own plants. Now, if the governor wants anything built, all he can do is try to encourage the market by signaling his support for private construction, with state-issued proposal requests, or offering an energy contract to a preferred plant via the New York Power Authority.

The mayor has even less power over the power grid. He is one of the most green-friendly mayors on the planet, and he has traveled the world extolling his efforts to experiment with bridge-top windmills, but he does not even have the power to renovate the kerosene-guzzling plant in Astoria. NRG, the Astoria plant’s owner, has already lined up its permits and community support, but it will only begin construction after bank financing comes through. And banks want to know there are energy customers lined up. Which is more of an issue, so long as Indian Point still generates its 2,000 megawatts.

In the meantime, the folks at Entergy have their own ideas of New York City’s energy future. “With time, and a lot of effort, I think we’re on the right side of the issues,” says Rick Smith, the company’s vice-president. He is sitting in a conference room on an upper floor of the New York Times Building, at the offices of one of Entergy’s lawyers, overlooking the city below. “I think we will get our relicensing,” he says.

When Smith talks about replacing Indian Point, he does the same 2,000-megawatt math everyone else does and, in so doing, emphasizes each alternative’s downsides—air-pollution increases, a possible degradation of the grid. “Con Edison got it right when it cited Indian Point as really important to the grid,” he says. He plays up the greenness of nuclear power. “It’s basically a zero emitter.” He talks about the link between energy and the GDP, and he discounts conservation programs as cramping economic growth. “That kind of cuts counter to the city’s goal of creating jobs,” he says.

Sitting next to Smith is Jim Steets, director of communications for Indian Point, and together they begin to sketch their vision of a New York City populated with small nuclear plants dotted throughout the boroughs. “It’s a little like an aircraft carrier,” Smith says. “I think modular.”

“I grew up in grade school diving under the desk,” he goes on. “People still have the bomb theory, but a couple of generations down from now, everyone becomes more comfortable with nuclear power. That’s why we try so hard to get the facts out. Everyone who goes through the plant comes away with a better understanding.”

Steets pipes in. “The thing is, there isn’t really anything about dealing with radiation that we don’t understand.”

“You know,” says Smith. “I had an MIT professor, he did a presentation on Fukushima, and I said, ‘Listen, you have to explain what’s going on there and how it’s different from here.’ And he said to me, ‘Rick, you know what the problem is? Today we can monitor radiation to the finest detail, and we report it to the finest detail.’ ” This precision, industry officials believe, has distorted public opinion and led to overregulation; by their thinking, a little exposure to radiation isn’t a big deal. “Even the releases at Fukushima,” Smith says, “most of them would have very little effect on public health and safety.”

“Unfortunately,” Steets adds, “our detractors rely so much on fear.”

Smith nods in agreement.

“They refuse to look analytically.”