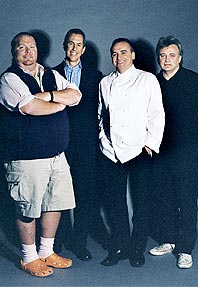

Danny Meyer

Restaurateur

Danny Meyer has been at the forefront of nearly every trend in New York dining, from Greenmarket menus (Union Square Café) to haute Indian (Tabla) to southern barbecue (Blue Smoke). Although his ventures may seem superficially disparate (one guy’s behind the Modern and Shake Shack?), each is an expertly executed elaboration on his original easy-to-love blend of highbrow and lowbrow, of the casual and the fancy—in other words, the dominant trope in restaurants today.

Mario Batali

Chef-restaurateur

Yes, Batali reinvented Italian cuisine as we know it, introduced legions of New Yorkers to beef cheeks and testa, and injected a welcome dose of Falstaffian indulgence into the post-nouvelle-cuisine world (lardo, anyone? A quartino of Barolo? A double-cut pork chop?). But walk into Babbo, the signature venue among Batali’s far-flung restaurant ventures, on a Saturday night, note the indie actors in the corner, the U2 pumping from the speakers, the party-happy attitude of the staff, and you’ll see that the one thing that Batali did that trumps the rest is this: He gave high-quality uptown cooking a big splash of downtown cool.

Jean-Georges Vongerichten

Chef-restaurateur

Not so long ago, eating at an haute French restaurant was a hidebound affair—decades-old elegance, preserved in aspic. It was Jean-Georges, trained in both France and Thailand, who opened up the four-star palate, lightening sauces, bringing Southeast Asian ingredients into the mix, and hiring hotshot designers to glam up his dining rooms. Vongerichten’s flagship restaurant and main laboratory, Jean Georges, set a new standard for high-end eating, and Vongerichten has built an empire of four-star restaurants—from Rama in London to Dune in the Bahamas to Jean Georges Shanghai—becoming, in the process, the iconic jet-lagged super-chef.

Keith McNally

Chef-restaurateur

McNally’s restaurants have an almost mystical ability to please. You certainly wouldn’t call Balthazar, Pastis, or Schiller’s Liquor Bar an authentic French bistro—with their uniform tiled floors, big mirrors, and steak-frites, they’re more like Disneyfied New York re-creations. But that’s not the point. The secret here is the glamorous patina—the illusion of European cool—along with familiar, comforting, and always tasty food. McNally has also become something of a de facto real-estate developer. He doesn’t invent the next hot neighborhoods, but he has a seemingly psychic ability to jump in at just the right moment (Pastis in the meatpacking district, Schiller’s on the Lower East Side). And where he goes, the masses follow.

David Chang

Chef-restaurateur

Chang’s Momofuku Noodle Bar upped the ethnic-food ante. In a city with some of the best Chinese, Japanese, and Korean food outside of China, Japan, and Korea, how do you raise the bar on a simple bowl of noodles? Answer: Momofuku. By adding luxurious ingredients (Berkshire pork) and Boulud - and Craft-honed techniques (he trained at both places) to formerly humble Asian staples, Chang has brought a new level of skill, and deliciousness, to inexpensive ethnic food. Given the crowds that keep lining up on First Avenue, there’s not a pizza-maker, hot-dog vendor, or mu-shu slinger who isn’t, or shouldn’t be, taking notice.

David Rockwell and AvroKO

Restaurant designers

Big-box restaurants—think ofBuddakan, Del Posto, Morimoto —are as much a part of the New York dining scene today as pork belly and tilapia. They’re vast, dramatic spaces designed for a memorable, almost theatrical evening, and they’re all derived, to some degree, from Rockwell’s templates: Nobu, Tao, Rosa Mexicano. The AvroKO team (Adam Farmerie, William Harris, Kristina O’Neal, Greg Bradshaw), meanwhile, has emerged as an innovator of the intimate. The leading-edge design firm’s handful of restaurants—Public, Stanton Social, Sapa—express fanatic attention to detail: the just-so brick walls, the vintage-style lamps, the painstaking selection of a font for the menu. It’s as if you’re in the home of an architect-designer couple who’ve made their apartment their life’s work. Food: Rick Bishop, Frank Bruni, Audrey Saunders …

Rob Sopkin

Director of new stores, Starbucks

This is the man who made the made the coffee shop an endangered species. Starbucks shops have a way of changing a block. They bring gourmet joe, of course (at $1.79 per cup). They provide public space for first dates, wireless office work, and emergency bathroom stops. And they can be a magnet for gentrification (they’re definitely a marker of it). The man responsible for where the Seattle-based Godzilla leaves its footprints in New York is Sopkin. Leading a team of twelve location scouts, Sopkin has added 200 Starbucks to the landscape in the past eight years, from such obvious places as Times Square to such formerly chain-averse neighborhoods as the Lower East Side and Brighton Beach. This is influence through ubiquity.

Rick Bishop

Owner, Mountain Sweet Berry Farms

Bishop isn’t the only farmer who sells ramps—the pungent, sweet wild leeks that ate Manhattan menus a few years back and return, to food fanatics’ delight, for a few short weeks every spring. But Bishop, along with fellow forward-thinking Greenmarketeers like Alex Paffenroth and Ted Blew, deserves much of the credit for Manhattan’s fresh-produce revolution. Over the years, Bishop has brought not just ramps but fragrant little local strawberries, wild watercress, fiddleheads, and Italian shell beans from borlotti to zolfini to the streets of downtown Manhattan. Paffenroth, for his part, pushes formerly rare roots like salsify and burdock. Blew’s Oak Grove Plantation has thirteen varieties of basil, from plain-old Italian to Mexican and Armenian. Together, Bishop and company (with the help of Danny Meyer and other fresh-ingredient-obsessed chefs) have helped awaken New Yorkers’ palates to the pleasures of fresh, locally grown, seasonal ingredients.

Audrey Saunders and Sasha Petraske

Lounge owners, mixologists

Saunders and Petraske have made high-end cocktails the new recreational drug. Their respective watering holes, Pegu Club and Milk & Honey, bring four-star seriousness to what, for the past 40 years or so, has been a Shake-n-Bake approach to drink-making. They revive forgotten quaffs (ever had a cobbler?) and invent new ones (the Gin-Gin Mule) to such delicious effect that ambitious bars, and even restaurants, around town have begun hiring their own top-shelf mixologists to keep ahead on the cocktail curve. That these two would usher in the next wave of cocktail culture should come as no surprise—both are disciples of the original master, Dale DeGroff, who invented a drink or two of his own back at the Rainbow Room.

Saru Jayaraman

Executive director, Restaurant Opportunities Center—New York

Up until April 2002, potato peelers, dishwashers, and other low-wage restaurant workers were among the most powerless laborers in New York. But Jayaraman’s Restaurant Opportunities Center is changing that. At age 17, the activist prodigy founded her first organization, Women and Youth Supporting Each Other; today WYSE has twelve chapters in six states. Now a Harvard-and-Yale-educated lawyer, she files lawsuits and leads protest marches against any restaurant—Brooklyn delisas well as places like Cité—that won’t give its workers a fair shake. In two years, Jayaraman’s efforts have won more than $300,000 in judgments, and though she tends to deflect praise onto those she represents, the oversize checks on her walls speak volumes.

Frank Bruni

Chief restaurant critic, the New York Times

In this Golden Age of restaurants, in which one or another famous four-star chef or talented upstart seems to open another notable establishment every day, the Times remains the publication of record for restaurant owners looking to impress. And when the high priest of star-giving confers, or withholds, his blessing, the cash registers ring, or don’t. Next: The Influentials in Sports