Four years ago, in the fading light of a chilly December afternoon, Jesse Louis Jackson Jr. arrived at a Chicago office building for the most important meeting of his political life. As the eldest son of the Reverend Jesse L. Jackson, Jesse Jr. was no stranger to high-powered summitry. When Jackson was an infant, Martin Luther King Jr. paid visits to his family’s tiny apartment; as a teenager, he accompanied his father to meet with presidents in the Oval Office; by the time he was a young man, and a key adviser to “Reverend” (as he often addressed his father), he was traveling the globe for encounters with Fidel Castro and Nelson Mandela. Now, as the representative for Illinois’s Second Congressional District, Jackson was a political player in his own right—someone whose time was in demand by any number of powerful people, including Barack Obama, who’d tapped Jackson as a co-chair for both his 2004 Senate bid and his just-concluded presidential campaign.

The man with whom Jackson was meeting that afternoon was not a world-historical figure. Illinois governor Rod Blagojevich was under federal investigation for corruption, and a recent poll had put his approval rating at 13 percent. And yet, as far as Jackson was concerned, Blagojevich was a political titan. It was his job to appoint the person who would fill Obama’s Senate seat—an appointment Jackson desperately coveted. Although he was just 43 years old, he had already spent thirteen years in Congress and was itching to move on to bigger things. “I grew up wanting to be just like Dad,” Jackson once said. “Dad wanted to be president.” He’d flirted with runs for U.S. senator and Chicago mayor as possible stepping-stones and was determined not to lose this opportunity. “He’d watched all these people whom he had helped pass him by, especially Barack,” Delmarie Cobb, a Chicago political consultant and a former Jackson adviser, says. “And he was like, ‘Wait a minute, I’ve got to do something!’”

Blagojevich and Jackson had once been friends. When they served together in Congress in the late nineties, they were so close that a colleague referred to the pair as “Salt and Pepper.” And when Blagojevich decided to run for governor in 2002, Jackson pledged his support. But then, according to people close to Jesse Jr., the Reverend Jackson intervened, urging his son to endorse a black candidate. “Junior said, ‘Reverend told me that I needed to shore up my base,’ ” one Jackson confidant recalls. “And he decided to take his dad’s advice.”

As a result, Jesse Jr. knew that, left to his own devices, Blagojevich would never appoint him to the Senate. So he launched an aggressive lobbying effort that would essentially leave Blagojevich with no other alternative. Jackson commissioned a poll that showed him to be the leading choice of Illinois voters to replace Obama. He secured endorsements from newspaper editorial boards and Illinois politicos. He even turned to his family’s celebrity friends. In a memo prepared for Bill Cosby, Jesse Jr. furnished the comedian with the governor’s home telephone number, the correct pronunciation of his name (“Blah-goy-a-vitch”), and talking points in favor of his appointment. “My strategy was to run a public campaign,” Jackson later explained, “as public as possible.”

But the campaign to get Jesse Jr. to the Senate also had a private side. Four days before the presidential election, Raghu Nayak, a Chicago businessman and a longtime friend and supporter of the Jacksons, approached Robert Blagojevich, the governor’s brother and chief fund-raiser, with a proposal. If Rod Blagojevich appointed Jesse Jr. to fill Obama’s Senate seat, Nayak and his friends in Chicago’s Indian community would raise $6 million for the governor’s reelection campaign.

Initially, the governor was not moved. As he infamously explained to an aide, unaware that the FBI had tapped his phone: “I’ve got this thing and it’s fucking golden, and … I’m just not giving it up for fuckin’ nothing.” He told another aide that the thought of appointing Jackson was “repugnant” and that “I can’t believe anything he says.” But as Blagojevich repeatedly tried and failed to auction off the Senate seat—for monetary and political concessions—his opposition to Jesse Jr. seemed to soften. For weeks, Jackson had been seeking a meeting with Blagojevich, with whom he hadn’t spoken in four years, to discuss the appointment. On December 8, 2008, the governor finally granted him one.

For 90 minutes, the erstwhile friends, along with Blagojevich’s chief of staff, met in the governor’s Chicago office, one of the few places in Blago’s world the Feds hadn’t bugged. Jackson began the conversation with a mea culpa, apologizing to Blagojevich for not endorsing him in 2002. Then he proceeded to make the case for his appointment. He presented a binder full of polling data, newspaper endorsements, and letters of support. He also pledged that, if appointed, he would run with Blagojevich when both men were up for election in 2010. At no point, according to the subsequent sworn testimony of all three men who attended, was there any discussion of money. When the meeting was over, Blagojevich seemed impressed and told Jackson that it had been a good interview and he would soon have him back for another.

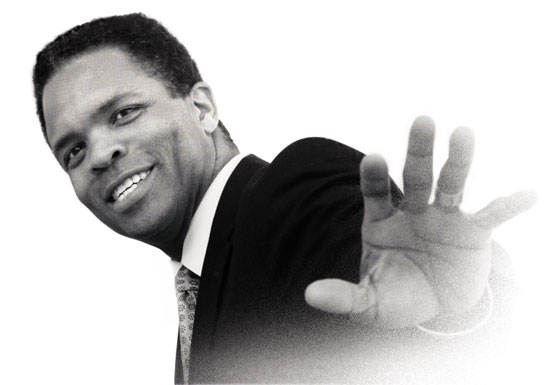

Jackson was elated. That night, he confided to friends that he believed he was on the verge of getting the appointment. He seemed to be at a pinnacle. He was almost the same age his father had been when he first ran for president. Smaller and less somber than Reverend, with lively eyes and a ready smile, he was in the best physical shape of his life, having lost nearly 100 pounds thanks to bariatric surgery and a rigorous exercise regimen. And now he was about to be a United States senator. “Junior felt really good,” one of his friends recalls, “like this thing was finally going to happen.”

The next morning, Jackson awoke to the news that Blagojevich had been arrested on corruption charges for, among other things, trying to sell Obama’s seat. Even worse, Jackson soon learned that the politician referred to in the indictment as “Senate Candidate Five”—who Blagojevich was heard on recordings saying had offered, through an associate, “pay to play” in exchange for the seat—was him. “All of his hopes were dashed,” Jackson’s friend says. “He went from as high as a person can be to as low in twelve hours.”

In a panic, Jackson got on the phone. One call was to his father, who, in turn, dialed his old friend Raghu Nayak and conferenced his son in. Jesse Jr. asked if the FBI had been in touch with Nayak; yes, he said. Another phone conversation Jackson had that day was with a lawyer in the U.S. Attorney’s Office. According to Natasha Korecki’s new book on the Blagojevich case, Only in Chicago, Jackson was seeking assurances that he himself wasn’t about to be indicted when he confessed: “I’m somewhere between a nervous breakdown and insanity.”

In the four years since, Jackson’s predicament, and his state of mind, have only deteriorated. Although he steadfastly maintains that he did not authorize Nayak, or anyone else, to bribe Blagojevich—nor has he ever been charged—the episode has cast a dark cloud on his career. Nayak, who was indicted this summer on unrelated fraud charges, has told federal investigators that Jackson did indeed put him up to a pay-to-play scheme. Nayak also told investigators that he twice paid, at Jackson’s request, for a Washington cigar-bar hostess and swimsuit model to fly to Chicago to visit the congressman—a revelation that, when it was leaked to the Chicago Sun-Times, ultimately forced the married Jackson to publicly admit to adultery. He is currently facing not only a House Ethics Committee investigation into the Blagojevich matter but also a separate federal criminal investigation into whether he used campaign money to decorate his Washington home.

This past June, Jackson took a medical leave from his House seat and disappeared. For weeks, the public—and even members of his congressional staff—did not know what was wrong with Jackson or where he was. Finally, in late July, the Mayo Clinic in Minnesota revealed that Jackson was being treated there for what was eventually diagnosed as bipolar disorder and depression. He was released in September, then readmitted last month. Although he is almost certain to be reelected to his ninth term in Congress this week, it remains unclear whether he will ever return to his job—and there is much speculation in Washington, D.C., and Chicago that he will resign soon after he wins.

Some of those closest to Jackson believe his medical problems resulted from, or were at least triggered by, his recent political difficulties. “He thought he was going to be a senator. He thought he was going to have a chance to run for mayor,” his mother, Jackie Jackson, told a group of supporters in July. “And young people don’t bounce back from disappointment like me and my husband.” But Jackson’s troubles may stem from something much deeper than mere disappointment. His is the story of a tremendously gifted politician who has spent his life wrestling with a legacy—and a man—that has been both a blessing and a curse. “After the Blagojevich stuff, he was obviously dead man walking as far as him moving up the ladder, but I don’t think anyone thought it would get to what it is now,” says a prominent Illinois Democrat who was once close to Jackson. “I think he knew that his name played a large part in getting him to where he was, but he also realized that his name would always hold him back from achieving his ultimate goals. And I’m not sure he ever figured out how to deal with that.”

His name was almost Selma. In March 1965, Jesse Jackson, then a 23-year-old seminary student and a disciple of the Reverend King, was traveling in Alabama when he stopped at an Esso station’s payphone to call his wife, who, when he left on the trip, was heavily pregnant with their second child. As he kept a wary eye out for the Alabama State Police, Jackie informed him that she’d given birth to a son. Seized by the moment, Jackson told his wife he wanted to call the boy Selma, where he had just been with King and other civil-rights activists to protest the “Bloody Sunday” march. But Jackie wouldn’t go along. She decided that their eldest son would carry his father’s name.

As it turned out, the name Jesse Jackson would become almost as iconic in the history of the civil-rights movement. And as his father’s renown grew, Jesse Jr., along with his four siblings, became children of that movement. The Jackson family’s stately Tudor-style house in Chicago’s South Shore neighborhood, which was purchased for the reverend by some of his wealthy benefactors when Junior was 5, was constantly swarming with activists, politicians, and celebrities. When Jesse Jr. wasn’t at home, he was usually being passed from lap to lap at his father’s political organizations, first Operation Breadbasket and later push (People United to Save Humanity).

While the elder Jackson, who was born out of wedlock to a 16-year-old girl in South Carolina, grew up hearing taunts of “Jesse ain’t got no daddy,” his own children had the opposite problem. “One of the first things I became conscious of was that many of my classmates knew me before I knew them,” Jesse Jr. wrote in A More Perfect Union, his 2001 memoir and political manifesto. “[T]here I was, the child of the newsmaking agitator. Some of my friends liked him and some didn’t—probably reflecting their parents’ attitudes—but I didn’t understand enough of what my daddy did to adequately explain it to them. That situation was often hard to deal with.”

So were the expectations. “He looked so much like his father and he acted like him in so many respects and just being the Junior, he was the anticipated successor,” recalls Calvin Morris, a Jackson associate from the Breadbasket days. After Jesse Jr., at the age of 5, clambered atop a milk crate and addressed a Breadbasket meeting, mimicking his father’s gestures and cadences, that sentiment deepened. “I grew up in a house with great expectations,” Jackson told the Chicago Tribune in 1995. “If I want to be a lawyer, that’s not enough. I need to be a Supreme Court justice one day. If I wanted to be an elected official, that’s not enough. ‘One day, son, you may be president.’ ”

At first, Jesse Jr. seemed to wilt under the pressure. As a rambunctious boy, he earned the nickname “Fella”—as in the “baddest fella” on the block. He became such a handful that when he was 12, his parents sent him to a Catholic military school in Indiana, where he received regular paddlings for “conduct unbecoming a cadet.” When his father began to consider a run for the presidency, he sent Jesse Jr. to the Washington prep school St. Albans to be educated “with the Mondales and the Bushes,” as the Reverend Jackson later explained. There, Jesse Jr. became a standout football player but struggled academically and was twice suspended—one time for sneaking a girl into his dorm room and the other for cheating on a calculus test.

It wasn’t until Jesse Jr. went to North Carolina A&T State University, the historically black school where his parents had met, that he seemed to find his niche—and one far different from the one his father had occupied. While Jesse Sr. had been the Aggies’ star quarterback and a member of Omega Psi Phi, Jesse Jr. quit football after one season and never joined a fraternity. Instead, he fell in with a group of “geeky, civil-rights, philosophy nerds,” as Mark Anthony Middleton, one of Junior’s best friends at A&T, puts it. He was active in politics, organizing anti-apartheid demonstrations and voter-registration drives, but he was primarily a behind-the-scenes player. Rather than run for student-body president, as his father had, Jesse Jr. managed the campaigns of his friends. “He decreased so that we might increase,” Middleton recalls. “He didn’t want to be out front.”

After college, Jesse Jr. stayed in that role, becoming a top adviser to his father and, in the process, forging a far closer relationship with a man who, for much of his life, had been a remote figure. In the early nineties, Jesse Jr. was appointed national field director of the Rainbow Coalition and set about trying to bring some order to his father’s notoriously chaotic political operation. Working in the group’s headquarters in Washington, he installed a then-state-of-the-art computer system and created a weekly fax newsletter, JaxFax, that provided talking points to clergy, college professors, and radio stations. He wanted to build the Rainbow Coalition into a real national political organization—one that wouldn’t exist just to assist his father’s quixotic presidential campaigns but would support, and actually help to elect, candidates up and down the ballot. In the process, he hoped that he might instill in his father a discipline and political focus that he’d always lacked.

But his father resisted. Part of it was generational. “Reverend was a technophobe,” Frank Watkins, a longtime Jackson adviser who was the coalition’s political director at the time, says. “He accused Jesse and me of loving computers more than loving people.” But the elder Jackson also seemed threatened by his son’s plans. “Reverend was about Reverend,” one Jackson adviser says. “He just wanted to keep Rainbow the way it was.”

Eventually, Jesse Jr. grew tired of the fight. One day in the early nineties, he unburdened himself to the late journalist Marshall Frady, who was writing a biography of the Reverend Jackson. “He won’t listen,” Junior complained of his father. “We keep telling him, ‘Why won’t you listen to us? We don’t want anything from you or anything. You can trust us.’ ” In obvious anguish, the heretofore dutiful son went on: “I’ve given it over six years of my life. Now I’m gonna go off and prepare myself to make my life. It’s time. I got to. Then I can come to him, you know, from a foundation of my own, and then maybe he’ll listen more. But I’ve got to start making my life now. Doing something myself.”

One morning not long after Jesse Jackson Jr. was elected to Congress in 1995, he boarded a flight at O’Hare for Washington. As he walked down the jetway, a cameraman from a Chicago station trailed after him, but blocking the path, and putting his hand over the lens, was Jesse Jackson Sr. Later that day in Washington, the same cameraman was trying to film the new congressman as he chatted with his colleague John Conyers—when, once again, the Reverend Jackson placed his hand in front of the lens. It was then, according to Delmarie Cobb, who was the younger Jackson’s campaign press secretary at the time, that Jesse Jr. pulled his father aside. “This is completely disrespectful to me, and you would have a fit if I did this to you,” he said, seething. “You will not do this to me again.”

The tension was not surprising. The Reverend Jackson had been against the idea of his son’s running for Congress from the very beginning—he thought he should aim for a lower office. To which Jesse Jr. responded: “If a 26-year-old Patrick Kennedy can be in Congress, then a 30-year-old Jesse Jackson Jr. could be there, too.” Although the Reverend Jackson ultimately relented, campaigning and raising money for Jesse Jr., he seemed uncomfortable sharing the spotlight. On the night Jesse Jr. won the five-candidate Democratic primary (and, thus, essentially the race), the Reverend Jackson insisted on introducing his son at the victory party and spoke for so long that he knocked Jesse Jr. off the ten-o’clock news. A few days before Junior was elected, the Reverend Jackson, who’d been living in Washington for nearly a decade and serving as “shadow senator,” announced with great fanfare that he was returning to push and Chicago, knocking his son off the front pages of the Sun-Times and the Tribune.

What most rankled Reverend was that Junior’s entire approach to politics seemed to be a rebuke. The younger Jackson’s aides—a number of whom had worked for the Reverend Jackson—told potential supporters: Junior is not his father. He really is going to work hard. He was a stickler about making votes, missing not one during his first thirteen years in Congress, and he shied away from publicity. “I’ve had ten press conferences in ten years. My father had ten press conferences yesterday,” he liked to joke. He fought for and won a seat on the Appropriations Committee and began bringing buckets of federal dollars back to his district. John Schmidt, a prominent Chicago lawyer, recalls a meeting with Jesse Jr. when Schmidt was running for governor in 1998. Jackson wanted to give him a tour of his district, and Schmidt had budgeted a couple of hours; the tour wound up taking the whole day. “He knew his congressional district at the level an alderman knows his ward,” Schmidt says. Most important, Jackson was more careful than his father around issues of race—frequently trying to reframe them as economic issues in order to broaden his appeal to white voters. “My dad needs to come out here and see this,” Jackson once boasted at a fund-raiser that was well attended by his white supporters. “This is a real Rainbow Coalition.”

But one skill Jackson gladly learned from his father was oratory. As a young man, he had closely studied his father’s speaking style, often mouthing along to his speeches, and by the time he arrived in Congress, he was a masterful speaker himself. That talent, combined with the ones his father didn’t share, led some aides to refer to him as “Jesse Plus.” “They said his father was a tree-shaker and not a jelly-maker,” Cobb says. “Jesse Junior was both.” The former Alabama congressman Artur Davis, who served with Jackson for eight years, ranks Jackson in the top ten of the approximately 250 members of the Democratic Caucus with whom he served. “Jesse Jr. was one of the more prodigious political talents of his generation, bar none,” Davis says.

And yet, in Washington, Jackson never quite mastered the rhythms of Capitol Hill. A Tae Kwon Do devotee, he’d sometimes be spotted walking through the marble halls of Congress in his dobok, and he seldom lingered on the floor to schmooze. His colleagues viewed him as something of an oddball and a loner. (People on the Hill say that it’s telling that the only congressman to visit Jackson at the Mayo Clinic has been Dennis Kucinich.) “He was not a guy who seemed to warm to the artificial camaraderie of the House,” Davis says. Although Jackson frequently claimed that he hoped to be the first black speaker of the House, his heart never seemed in the pursuit. “People who talk about wanting to be in leadership are rarely successful at it and he never really worked to cultivate those relationships with members,” a senior Democratic House aide says. “He was good at the presentation of politics, but the actual behind-the-scenes execution was always a little clumsy.”

Instead, Jackson’s focus was back in Chicago, where he was building a formidable political machine. In the basement of his house, a block from Lake Michigan, Junior constructed a campaign war room. He filled it with computers, phones, even a giant mail machine capable of producing thousands of four-color mailers—and he would take candidates there to show them the political muscle he could provide if they earned his support. “He was meticulous in his preparation,” recalls Alexi Giannoulias, who sought and received Jackson’s endorsement for his 2006 state treasurer’s campaign. “When I met with other people, I’d say, ‘Here’s why I want to run.’ I’d give them my heartfelt pitch about why I wanted to be in public office. With Junior, he’d say, ‘I want to hear your pitch, but I also want to see polling, how much money you’re going to raise, who’s running your campaign. Give me the numbers and the names.’ ”

Jackson began to assemble what some around him called a “farm team.” He seeded the Chicago City Council, local county commissions, the Illinois State Legislature, and state executive offices with his allies. At one point, he helped his minister get elected to the State Senate; a few years later, he spearheaded his wife Sandi’s successful campaign for Chicago alderwoman. Meanwhile, Jackson worked to build up his fund-raising base. Some traditional Democratic patrons, including Jewish Democrats, were off-limits. “He doesn’t have a great calling card with North Shore lakefront liberals because they’re very suspicious of the Jackson family,” one prominent Illinois Democrat explains. So Jackson created new donor groups, cultivating relationships, for instance, with members of Chicago’s growing and increasingly wealthy Indian community, including Raghu Nayak.

And then there was his signature issue: the construction of a third airport in the cornfields 40 miles south of Chicago. Junior argued the airport would be an economic-development engine for the whole South Side. But it would be a political engine for him, too. For years, O’Hare, which is run by the City of Chicago, had been a major patronage operation for Mayor Richard Daley and other Chicago politicians. The new suburban airport would be managed by a commission that was dominated with Jesse Jr.’s supporters, giving Jackson his own patronage candy bowl. No one in Chicago was entirely sure what Jesse Jr. intended to do with the political machine he was building, but one thing was clear, says a prominent Illinois Democrat: “It was designed for something bigger than getting reelected to represent the Second District every two years.”

A U.S. Senate seat was bigger, and Jackson began eyeing the one held by an unpopular Republican who would be up for reelection in 2004. “That seat had Junior’s name on it,” says Hermene Hartman, a longtime Jackson family friend. Then, in the fall of 1999, a riot broke out at a high-school football game in Decatur, Illinois, leading to the expulsion of several black students. The Reverend Jackson protested their expulsions—comparing Decatur to Selma and saying the students were victims of racism—and eventually went to jail for his efforts. A video subsequently emerged showing the students had indeed incited the riot. The Reverend Jackson looked like a fool. “Jesse Jr. said, ‘There’s no possibility that I could win the election,’ ” Frank Watkins, Jesse Jr.’s longtime press secretary, recalls. “ ‘My dad was recently in jail in Decatur, and I’m going to go down there and ask for their vote?’ ”

A young state senator named Barack Obama did not have that sort of baggage, and in 2002, he met Jesse Jr. at a Chicago restaurant. Michelle Obama had been a Jackson-family friend for years, having gone to high school with Jackson’s older sister, Santita, and Jesse Jr. (who once confessed to having a boyhood crush on Michelle) had attended the Obamas’ wedding. Over breakfast, Obama told Jackson that if he planned to run for the Senate seat, Obama wouldn’t, but if Jackson wasn’t running, could Obama have his support? Jackson gave it to him, putting his basement war room at Obama’s disposal and appearing on billboards and mailers with him. For Obama, who had lost a congressional race in 2000 over doubts about whether he was “black enough,” Jackson’s backing was crucial.

Four years later, when Obama ran for president, Jackson was there to help again. He leaned heavily on his fellow members of the Congressional Black Caucus to support Obama, going so far as to threaten primary challenges against those who’d endorsed Hillary Clinton—a move that particularly rankled older black congressmen, like Charlie Rangel and John Lewis, who’d known Junior since he was a child. But Jackson’s biggest battles on behalf of Obama were with members of the Jackson family, many of whom were supporting Clinton. When his mother Jackie cut a radio ad for Clinton in South Carolina, the Obama campaign had already aired one that Junior made there; he also worked to raise money for Obama in order to offset the $100,000 his brother Yusef raised for Hillary.

Jesse Jr.’s thorniest task was managing his father. Although the reverend had endorsed Obama, he didn’t always act like it—complaining to a South Carolina newspaper that Obama was “acting like he’s white” and, most infamously, being caught by an open mike saying that “I want to cut [Obama’s] nuts off” for “talking down to black people.” In public, Jesse Jr. was blunt with his push back, saying that he was “deeply outraged and disappointed in Reverend Jackson’s reckless statements” and that his father “should keep hope alive and any personal attacks and insults to himself.” Privately, he was even more pointed in what he said to his father, telling one Democratic strategist, “I smacked him down.” By the time Obama was elected, there was so much ill will in the Jackson family that Jesse Jr. and his younger brother Jonathan, best friends since childhood, were barely on speaking terms.

But Obama and his advisers did not reward that loyalty by helping Jesse Jr. get what he most wanted: Obama’s Senate seat. Shortly before the election, Obama dispatched emissaries to tell Blagojevich that he hoped the governor would appoint his adviser and friend Valerie Jarrett—and that Obama explicitly didn’t want the seat to go to Jesse Jr. Indeed, Obama’s aversion to Jesse Jr. was so pronounced that Blagojevich and his aides eventually came to view appointing Jackson as a way to punish Obama for not offering Blagojevich anything in exchange for appointing Jarrett. “That would be revenge,” one Blagojevich aide told his boss.

Part of the Obama team’s reluctance about Jackson was political. Obama’s advisers were never sold on the idea that Jackson could hold on to the Senate seat when it came up for reelection in 2010. “They put Jesse in the box of being an urban black politician, of being Jesse Jackson’s son, who couldn’t win a statewide race,” says one person who participated in conversations with the Obama team about the Senate appointment. But it also may have been personal. “I don’t think Barack ever trusted Jesse,” says one Illinois Democrat, who was friendly with both Jackson and Obama. “He was just suspicious of him.”

The suspicion was mutual—and perhaps inevitable. One prominent Illinois Democrat remembers running into Jesse Jr. at the 2004 Democratic convention the morning after Obama’s keynote address: “We knew something special had happened, and everyone from Illinois, especially everyone from Chicago, was happy—everyone except Jesse. He was like, ‘What the fuck? This guy just hurdled over me.’ ” Once considered the most prominent young black politician in the United States, Jackson could no longer even claim that honor in his hometown.

After Obama failed to go to bat for Junior on the Senate appointment, or offer him a job in the administration, that suspicion curdled into outright bitterness. “He seemed very sore at the president,” one person who discussed the matter with Jackson says. “He felt the president really just forgot him and kind of left him out. Junior viewed himself as having made a king and people, including the king himself, didn’t appreciate that.”

On Saturday, June 10, Jackson appeared from Chicago, via satellite, on Melissa Harris-Perry’s MSNBC show. He was touting a bill he had just introduced to raise the minimum wage. “This is not welfare,” Jackson said. “These are people who are working hard every day, and at the end of a hard day’s work, they can’t keep up with the Consumer Price Index.” That afternoon, after Jackson had flown back to Washington, he called Watkins to check in. “He was talking about, ‘Man, the minimum-wage thing is driving these right-wingers crazy,’ ” Watkins says. “He was really pumped up about that.”

But that evening, Jackson’s mood apparently darkened. According to an account his wife, Sandi, later gave to the Chicago Sun-Times, Jackson was in his Dupont Circle home by himself. (Sandi and the couple’s two children were in Chicago.) “His father, Reverend Jackson, called him on the phone and felt he didn’t sound right,” Sandi told the newspaper. “Jesse told his father he was so exhausted, he couldn’t take another step.” It was then that the Reverend Jackson and Jesse Jr.’s brother Yusef went to the congressman’s house and rushed him to George Washington University Hospital.

Jesse Jr. had in fact been struggling for some time. He had long suffered occasional but violent mood swings—laughing one moment, sobbing the next—so much so that nearly a decade ago members of his staff half-jokingly diagnosed their boss as bipolar. His condition worsened dramatically after the disappointment of not getting the Senate seat and the stress of the subsequent investigation and revelation of his adultery. The congressman who prided himself on never missing a vote became an absentee legislator. “He did absolutely nothing,” says former Illinois congresswoman Debbie Halvorson, who served in the House with Jackson in 2009 and 2010.

Earlier this year, however, Jackson was reenergized. Halvorson, who’d lost her reelection bid in 2010, ran against Jackson in the Democratic primary for his redrawn district—the stiffest electoral test he had faced since 1995. Jackson rose to the challenge, pouring himself into the campaign and, in March, he thumped Halvorson by taking more than 70 percent of the vote. But soon after his victory, he plunged into a deep funk. This may have been brought about by the fact that the FBI had opened an investigation into whether he’d used campaign money to decorate his home. But it seems just as likely that Jackson, having worked so hard to hold onto his seat, now had to confront the crushing reality that all of his effort had merely resulted in his remaining in the same place. According to a friend, Jackson began “drinking heavily, self-medicating, and going days without sleep. He was out of control. He was on a path that was self-destructive. Something had to change.” Indeed, although Sandi portrayed her husband’s hospitalization that night in June as a spur-of-the-moment decision, others close to Jackson suspect it was the result of a planned intervention—something the congressman’s friends and family had been discussing for weeks.

Five days after his father and brother took him to the hospital in Washington, Jesse Jr. checked in to the Sierra Tucson Treatment Center in Arizona, a facility a family friend had recommended because of its reputation for privacy. That discretion initially enabled Jesse Jr. to keep his condition a secret: It took more than two weeks for his congressional office to announce that he’d taken a medical leave of absence and even then his spokesman said it was for “exhaustion.” But when Jackson transferred to the Mayo Clinic for more intensive treatment in late July, he could no longer keep his whereabouts or condition under wraps. After receiving inpatient treatment at the Mayo Clinic for more than a month, he returned to his home in D.C., where he received extensive outpatient treatment, visiting with his doctor twice a day. But even that proved insufficient, and in late October, he returned again to Mayo. Jackson and his doctors still have no timetable for getting him back to work.

In addition to medical help, Jackson has been seeking political counsel, especially from the man whose nepotistic presence in Congress he once derided: Patrick Kennedy. Kennedy, who was treated at the Mayo Clinic for depression before he retired from the House in 2010, has visited Jackson in Minnesota and at his Washington home and has been struck by his former colleague’s condition. “He has always carried himself with a certain force of personality, and you could clearly tell what a grip this illness has had on him,” Kennedy says. “He was dealing at the most basic level with a sense of himself and with this overwhelming feeling of inconsolable grief. He was clearly debilitated.”

In his conversations with Jackson, Kennedy has encouraged his former colleague to think about a life beyond electoral politics—and to place his struggles in a broader context. “I’ve told him, ‘You’re going to be a great champion for the case of mental health because it’s a civil-rights cause, too,’ ” Kennedy says. “His father wore the mantle ‘I am a man,’ and it was a mantle that said, ‘Don’t dehumanize me because of the color of my skin.’ Now Jesse Jr. can wear that mantle in a new era, where the stigma has less to do with the color of his skin than the type of illness he’s suffering from.” Jackson, for his part, asked Kennedy to speak to Jackson’s father, who hasn’t been as receptive. “I think his father, like my father, comes from a generation where these issues aren’t spoken about,” Kennedy says.

In fact, the Reverend Jackson may have far more immediate political concerns. Although Jesse Jr. is all but certain to be reelected on November 6, his future in Congress is very much in doubt. In Chicago, his decision to remain on the ballot has been interpreted not as a sign of his intention to stay in office but as a gambit to deny the local Democratic bosses the opportunity to appoint his replacement. “I think the strategy is to push this past the election, to give him time to work things out with the doctors or the prosecutors or whomever,” a Chicago Democratic strategist says, “and then, if necessary, he’ll step down.” If that happens, Jackson’s seat would be filled through a special election. An open House seat on Chicago’s South Side would set off a political free-for-all, and already a number of state legislators and aldermen are positioning themselves. But the fighting for the Second District seat could be the most intense among the Jacksons themselves.

If the Jacksons want to keep the seat in the family, as many believe they do, Sandi Jackson would seem to be the most logical candidate. She is already an elected official, and she had been prepared to take over the seat if Jesse Jr. had received the Senate appointment in 2008. But Sandi has long had a difficult relationship with the rest of her husband’s family. “They’ve never liked her from day one,” Delmarie Cobb, who was working for Reverend Jackson when Jesse Jr. and Sandi met in 1988, says. “They beat him up all the way down the aisle.” Initially, the Jacksons objected to their son’s choice of a spouse because she was a child of divorce. As time went on, they disapproved of Sandi because they believed she was a meddler: It was originally her idea that Junior should run for Congress, and, over the years, Jackson’s campaigns have paid Sandi more than $400,000 in political consulting fees.

All of which is why, according to multiple Chicago politicos, the Jackson family wouldn’t support Sandi’s candidacy. Instead, the family, and Jackie Jackson in particular, has been privately pushing Jesse Jr.’s younger brother Jonathan—a businessman who, in recent years, has occupied the aide-de-camp role for his father that Jesse Jr. once performed—as their preferred successor. “It’ll be Jonathan Jackson against some Establishment candidate,” the Chicago Democratic strategist predicts.

For the moment, though, the seat is still Jesse Jr.’s. A decade ago, Jackson and his advisers had penciled in 2012 as the year he might run for the White House. “I told him if we stayed steady on the case that we could change America,” Frank Watkins recalls. “His message was bigger and broader than his dad’s. They were talking about him the way they talk about Barack now. He was going to be the first black president.”

Instead, Jackson now finds himself campaigning for reelection to his House seat as a ghost. In late October, a few days before he returned to Mayo and a little more than two weeks before voters were to go to the polls, Jesse Jr. released his first public statement since he disappeared in June. In an automated phone call to households in the Second District, the congressman updated his constituents on his condition. “Like many human beings, a series of events came together in my life at the same time and they have been difficult to sort through,” Jackson said in a hushed, hollow voice that lacked its usual rich timbre. “I am human. I am doing my best. And I am trying to sort through them all.”