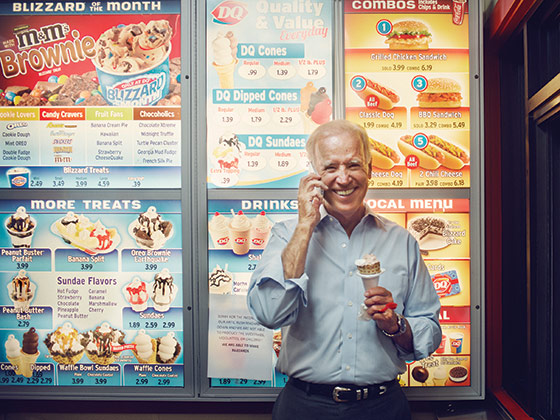

Jesus Christ!” Joe Biden barks, pitching forward in the captain’s chair in his cabin aboard Air Force Two. We have just departed Roanoke, Virginia, for Washington, D.C., after a three-day campaign swing through North Carolina and the Old Dominion, during which Biden has been on display in all his garishness and glory. He has given a series of scorching speeches aimed at Mitt Romney and his freshly minted running mate, Paul Ryan. He has mingled with the locals at a coffeehouse, a firehouse, a country store–cum–bluegrass showcase, and a high-school football practice (“You’ve started school already? That’s un-American!”). He has made an unscheduled late-night stop at Dairy Queen, inhaling a chocolate-and-vanilla-swirl cone. And, oh, yes, he has blurted out the latest addition to the epic Biden blooper reel—a question about which has now provoked him to take the Lord’s name in vain.

For the past 24 hours, Biden has been watching, fretting, and simmering as his remark before a substantially black audience that the Romney-Ryan plan to “unshackle Wall Street” would “put y’all back in chains” has ignited a flaming freak-show conflagration. An array of conservative ultra-Caucasians are accusing him of race-baiting. Representing the pot-and-kettle caucus, Rudy Giuliani is calling him stupid and Sarah Palin is spluttering that he is a drag on the Democratic ticket, while Romney himself has affected a tone of outrage so flagrantly faux—“the White House sinks a little bit lower”; “campaign of division and anger and hate”—that it qualifies as rhetorical trompe l’oeil.

The V.P. has so far largely held his tongue about the contretemps. But as we clear the runway, he sets that (in)famous organ free, emitting a succession of soliloquies by turns defiant, defensive, and indignant. “Look, I’ve been saying that exact same thing since [John] Boehner made his speech … where he used the phrase that you’ve gotta unshackle the economy, unshackle Wall Street,” he begins. “You got a whole bunch of examples of where I said, ‘The last time these guys unshackled the economy, they put the middle class in shackles—they shackled you’ … It’s the exact same thing Romney’s talking about: first, being able to do away with Dodd-Frank, and, man, if that happens again, the middle class is gonna get screwed.”

And: “I don’t make any distinctions with what I say to a black audience—and I have a better relationship with the black audience than anybody you know. I don’t think a single person in there who was African-American went, ‘My God, he’s saying Romney would put us [literally] in chains.’ By the way, would it be better if I’d used ‘shackles’? Yeah, that’d help!”

And: “What [the Republican reaction] does say to me is the desperation of Romney. You’d think after naming his vice-president, on their first magical mystery tour together, like Barack and I did, it would all be up, like it was after we got started. Obviously, it didn’t go so well or they wouldn’t be looking for this whole thing.”

Biden pauses and takes a breath. You think he’s finished. Foolish you. Air Force Two will be safely at cruising altitude before he brings his retort in for a landing with a one-fell-swoop dismissal of the Twitterverse, the blogosphere, the hot-eyed Foxified yakkety-yak-yakkers, Romney, Ryan, and, in a way, himself: “I don’t think this has a single little effect on voters.”

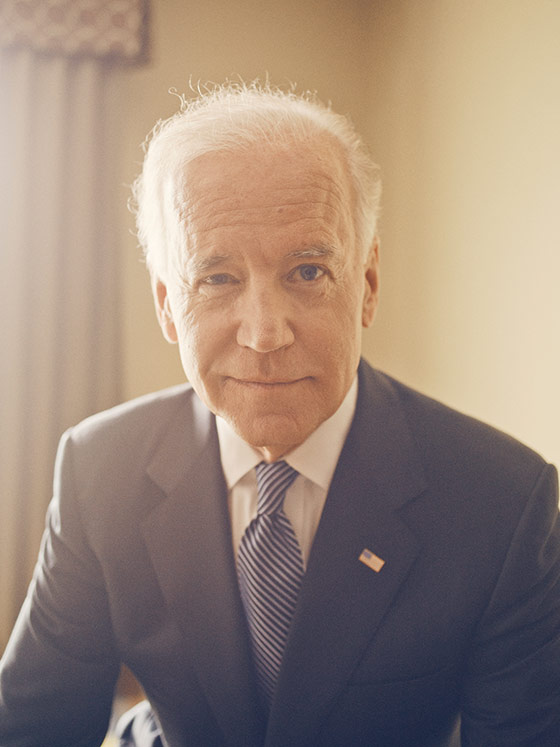

Joseph Robinette Biden Jr. has been in Washington for nearly 40 years, the first 36 as a United States senator from Delaware, the past three-plus as understudy to Barack Hussein Obama. (It should be said: Hussein and Robinette—what a country!) With a résumé like that, Biden is well aware that his assessment of the “chains” brouhaha could be readily applied to any vice-presidential candidacy in its totality: that, for incumbents and challengers alike, a running mate’s gig is severely limited in scope, tightly circumscribed in duties, and exerts an influence on the electoral outcome ranging from marginal to de minimis.

Until recently, Biden had no reason to see his role in this general election unspooling any differently. He would spend the fall doing what seconds-in-command always do, what he’d been doing for months already: wielding the hatchet, revving up the base, and shoring up Obama with working-class whites, old folks, and Jewish voters, mainly in Florida, Ohio, and Pennsylvania. He would uncork a honking oration at the Democratic National Convention this week in Charlotte, “tell[ing] a story about my guy and how he’s governed,” as Biden puts it. He would find himself debating (surely) Rob Portman or Tim Pawlenty—and no one would give a shit.

But then Mitt Romney pulled a rabbit from his hat and upended those expectations. In filling his V.P. slot with the 42-year-old cheesehead chair of the House Budget Committee and author of the seminal governing document of the congressional wing of the Republican Party, Romney injected a bracing dose of youth, substantive audacity, political risk, and partisan glamour (or what passes for glamour on the right) into a race that had been teetering on the edge of terminal torpor. Suddenly, with the spotlight trained on Ryan, whose speech last week at the Republican convention roused the hall and popped off the TV screen, Biden was bathed in luminescence, too. Suddenly, amazingly, the undercard mattered—with next month’s toe-to-toe between the No. 2’s elevated from a sideshow to a marquee event.

Biden, to be sure, has been here before; in 2008, his debate with Palin garnered a larger audience than any of the televised tangles between Obama and John McCain. The task before Biden this time around will be different, though, and not just because he isn’t seen as the prohibitive favorite. With Ryan now providing the ideological and intellectual heft on the GOP ticket, the Democrats intend to spend the next 60 days talking as much about him as about Romney. Yet the vice-presidential debate will be their only opportunity for direct engagement with Ryan—and Biden, not Obama, will be the one doing the engaging.

Thus is Biden facing the last great challenge of his last campaign. Unless, of course, it isn’t. Biden will turn 74 in 2016, and his poll numbers have sagged since he took office, but he and his people have been hinting that he might have another presidential bid in him. Some political observers regard this prospect as ludicrous: They see Biden as a clownish gasbag. Others greet it with delight: They see him as a national treasure. This is how it’s always been for Biden, with opinions about him diverging radically as if at a fork in the road of life—one that seems as fundamental as whether, deep down, you’re a Beatles or a Stones person.

But the truth about Biden is, in fact, more subtle and complex: that his greatest asset, what Obama strategist David Axelrod calls his “bluntness and ebullience,” is equally his gravest liability; that his old-school m.o. makes him almost uniquely unsuited to this postmodern political-media moment; that in a culture that pines ardently for authenticity and then punishes it cruelly, his utter incapacity for phoniness (and, yes, his grievous inability to control his yap) endows him with enormous charm and guile—and also renders him a human IED.

Biden is acutely sensitive to all of these perceptions of him. Some he shares, some he tolerates, others drive him batty. What he can’t abide is the concept that he has reached the end of the line. In a career riddled with tragedy and disgrace, with episodes of emotional, political, and even physical disaster and defeat, Biden always recovered, because he always had something left to prove. And whether it comes to Ryan or 2016, he apparently still does. “My friends are always kidding me about it—I can’t fathom the idea of thinking of retiring,” he declares. “Hell, man! I can still take ya!”

On election night four years ago, after Obama and Biden climbed down from the stage in Chicago’s Grant Park, the ticketmates shared a moment with Biden’s mother, Jean (who was then 91 and now is in a better place, as they say). As Biden tells it, his mom walked up, took Obama’s hand, and said, “Honey, come here, it’s going to be okay”—and then grabbed her son’s and offered him reassurance, too: “Joey, he’s going to be your friend.”

Among those who knew either man remotely well, this was not a common forecast back then. As much sense as Biden—a white guy with gray hair, blue-collar appeal, and foreign-policy cred—made as Obama’s V.P. pick, temperamentally and stylistically the two were chalk and Camembert. The campaign had done nothing to generate warmth between them; in fact, it brought a chill. Following the Democratic convention, they rarely stumped together and barely spoke by phone. As tensions mounted, Biden disgorged a series of gaffes that drove Obama to anger. On a conference call after his running mate publicly declared that “it will not be six months before the world tests Barack Obama” with a “generated crisis,” the nominee growled, “How many times is Biden gonna say something stupid?”

The frostiness continued through the transition and into the early days of the new administration. In February 2009, at the House Democratic Caucus’s annual retreat, Biden reported that, in a conversation between him and Obama about some aspect of policy, they acknowledged that even “if we do everything right … there’s still a 30 percent chance we’re gonna get it wrong.” Obama, asked about it later by a reporter, replied snidely, “I don’t remember exactly what Joe was referring to. Not surprisingly.”

But soon enough, in the hellish atmosphere of crisis that pervaded the first year, a thaw set in. In agreeing to be Obama’s No. 2, Biden had insisted that he be the last person with the president’s ear on every major policy decision. Not only did Obama honor that, but he offered Biden carte blanche to attend any Oval Office meeting that he wished. The vice-president found himself playing point on two crucial pieces of business, the stimulus and the drawdown of American forces in Iraq, and a key role in the review of Afghanistan policy.

Which isn’t to say Obama ever stopped cringing at Biden’s persistent indiscipline or sporadic outright blunders, but he came grudgingly to accept them as part and parcel of Biden being Biden. Obama’s West Wing aides, however, were often less forgiving. When, this past May, the V.P. sparked a firestorm by announcing on Meet the Press that he was “absolutely comfortable” with gay marriage, forcing his boss’s hand on the issue, Obama’s people, and especially White House senior adviser David Plouffe, were livid. And they made their displeasure loudly known, internally and to the press.

Prideful and possessing no diminutive ego, Biden felt bruised by his treatment but apologized to Obama—only to find the president a great deal less bothered than his inner circle. “Look, Joe,” Obama said, according to Politico’s Glenn Thrush in his new e-book, Obama’s Last Stand, “there are people who want to divide us. You and I have to be on the same page from now on.”

In fact, the same page is where Biden and Obama usually find themselves. Over time, a sense of personal chemistry has flowered alongside professional esteem. Biden warmly recalls that when, in the spring of 2010, his son Beau suffered a stroke, Obama came racing down the hall and gave him a hug. And the president—who Biden has told friends is “more Irish than me”—values the fierce loyalty the V.P. has demonstrated. Time and again, in public and private, Biden has dressed down anyone who has dissed Obama. (At a meeting of House Democrats in late 2010, Biden upbraided Anthony Weiner so forcefully and profanely that he earned a standing ovation.) “The stories all get back to Obama,” says a White House official. “He loves them.”

Biden admits that, unlike his mother, he was uncertain that he and the president would become pals. “My son’s more like Barack than I am like Barack,” Biden tells me. “And my son and Barack have the same exact core: They’re cool, they’re cerebral, they’re straight, they keep their passion in check. They’re the modern politician.”

But Biden sees an essential similarity between himself and Obama, generational differences be damned—illustrating the point by noting that they are both popular with college kids. “I think the bottom line is, what they like about Barack is Barack doesn’t pretend to be what he’s not, and I don’t pretend to be what I’m not,” Biden says. “It only matters what he thinks, but we both think we make a pretty good team: We’re an unmatched matched pair.”

Where Biden and Obama are in perfect sync is their attitude and approach to the matched pair on the Republican ticket. A few hours after Romney unveiled his V.P. pick, on August 11, Biden phoned Ryan to congratulate him and welcome him to the race; the call was cheerful and consumed mostly with talk of family. But Biden did offer Ryan one piece of advice: that he should be enjoying this moment, reveling in it, having a ball. What Biden might have added, if he were being candid, was: I know I am.

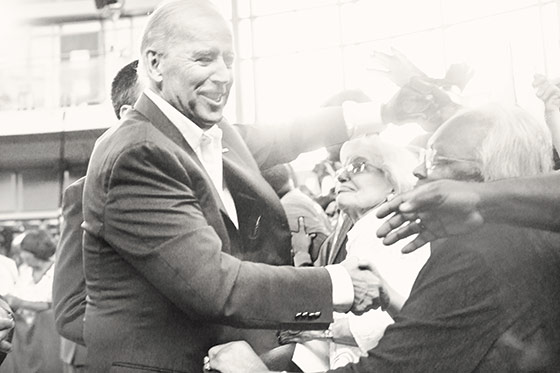

Forty-eight hours later, Biden launches his southern tour in Durham, North Carolina. The day before, an hour away in High Point, Romney and Ryan had held a rally that drew more than 10,000 souls. The crowd this morning at the Durham Armory is less than a tenth that size, but Biden doesn’t care. After unfurling a shaggy-dog story revolving around the two brain aneurysms that nearly killed him in 1988—a tale set entirely in Delaware but ending with a punch line, attributed to his wife, Jill, that goes, “Joe, if you die, I’m moving to North Carolina!”—he tosses bouquets to a congressman (“It really is wonderful just riding along in Butterfield’s wake”), a state senator (“Floyd helped me last time”), Durham’s mayor (“one of the president’s favorite mayors”), and a local T-shirt manufacturer (“I got coffee on my shirt here, so from here on out, I’m gonna be wearing one of your T-shirts”). Apparently immune to both apocrypha and pandering, the crowd roars with delight.

Yes, Joe Biden loves the stump—and it’s a good thing, too, since the stump is where he has been living for the better part of the past six months. Far in advance of the president, and even before the GOP had settled on its nominee, it was Biden who began the process of framing the argument against the Republicans with a series of major policy speeches in the spring and then in ripping Romney as a rapacious, secretive plutocrat devoid of empathy for ordinary people. “Chicago has been eager from the very beginning,” a top Biden adviser tells me, “for him to be the sharp tip of the spear.”

That’s the role Biden is playing this afternoon in Durham; his speech is the first full-throated response by either him or the president to Ryan’s selection. To say that Team Obama is laughing-gas giddy about the pick would be an overstatement, but just a mild one. All along, two of the Democratic side’s paramount strategic imperatives have been to keep the election from being a pure referendum on Obama’s economic stewardship, instead making it a choice between competing visions, and to paint Romney as a figure indistinguishable from the congressional wing of the Republican Party. And the Ryan selection has made both jobs much easier—just listen to Biden.

“This really is one of the starkest choices, not only important but one of the starkest choices for the American people, and it’s good that it’s a stark choice,” he declaims. “Congressman Ryan has given definition to the vague commitments that Romney’s been making … Congressman Ryan, a congressional Republican, as one person said, has already passed in the House what Governor Romney is promising to give the whole nation. And ladies and gentlemen, we know, we know for certain, what I have been saying for a long time: There is no distinction—let’s get this straight—there’s no distinction between what the Republican Congress has been proposing the last two years, actually the last four years, and what Governor Romney wants to do.”

For the next half-hour, Biden rattles through the specifics that he believes justify those damning charges. Yet it’s clear that for all of Biden’s distaste for Ryan’s conception of the proper role of government, his scorn for Romney and delight in deriding him are infinitely greater.

“I don’t have to tell people about outsourcing—you all get it,” Biden says. “And I love Romney’s answer: ‘There’s a difference between outsourcing and offshoring.’ ” At which point Biden falls silent, drops his chin to his chest, and, with mock solemnity, performs the sign of the cross. “You can just hear the conversation—two guys on the unemployment line, one guy turns and says, ‘Were you outsourced or offshored?’ ”

To listen to Biden, it’s not hard to grasp why Chicago has made him the campaign’s arrowhead. At a moment of pervasive economic anxiety and roiling ire at the one percent and its political enablers, Biden is the only person on either party’s ticket genuinely fluent in the language of populism. And at a juncture at which the Romney-Ryan operation has concluded that running up its margins with working-class and elderly white voters is its sole path to victory, Biden is the only one who can, you know, go there and not seem like a big fat fraud.

And the day after Durham, he does—bounding in to a diner in Stuart, Virginia (pop. 1,400), that seems plucked from another era. Inside the Coffee Break Cafe, on the town’s minuscule main drag, Biden finds two dozen patrons, all as unpigmented as he and most around his age, sitting at Formica tables under pictures of Chet Atkins, Rhonda Vincent (signed), and any number of nascar drivers. He also finds Glen Wood, a regular at the Coffee Break and founder of Wood Brothers Racing, the nascar team that won the Daytona 500 last year.

“I heard someone in here won the Daytona,” Biden bellows, pushing past a photographer and jovially saying, “Get out of the way, man,” as he makes a beeline to Wood. “This guy did what I dreamed of, man! I’d trade being vice-president in a heartbeat for having won the Daytona!”

Soon enough, Biden, holding a Coke in an old-school glass bottle, is chattering away with—more like at—the AARP-ish crowd: about unemployment, the “9/11 generation” of veterans, and his wife (joking that he and Obama “married up” to ladies who are “more popular than we are”). A woman excuses herself, explaining that she has to get back to work at a local Walmart, inviting Biden to stop by. Biden quips that he just might: “I’m like a poor relative; I show up if I’m invited. The rich ones never show up. The poor ones come, stay longer than they should, and eat your food.” And then quotes Harry Truman: “If you want to live like a Republican, vote Democrat.”

When the press confers honorifics on the V.P. such as “Obama’s de facto ambassador to white working-class America,” this is the kind of scene that leaps to mind. A scene featuring Regular Joe Biden, born in Scranton, Pennsylvania, son of a used-car salesman, graduate of the University of Delaware, honest-to-God hot-rod aficionado—“My first car was a ’51 Plymouth”—who didn’t blanch when The Onion spoofed him in 2009 with a story headlined “Shirtless Biden Washes Trans Am in White House Driveway.” (Biden’s only gripe was that they got the car wrong: He owns a 1967 Corvette, which the Secret Service won’t let him drive.) A guy, in other words, who can talk the talk and walk the walk, who can go places that his superior can’t.

Team Obama quails at the suggestion that the president is reliant on Biden to reach blue-collar whites. “I think that’s way overstated,” Axelrod maintains. “The president is hitting some of the same targets, just at different times. So I wouldn’t say we need an ambassador into those communities, but Biden extends our reach in a really important way.”

Biden agrees—sort of. “Here’s the thing, and this is gonna sound self-serving,” he tells me. “Whatever year Sam Nunn left the Senate in the nineties, I remember pollsters coming into the [Democratic] caucus and talking about the race and saying Sam and I were the only, if memory serves me, two Democrats in the United States Senate who still got a majority of the white-male vote. No Democrat gets it! Barack’s no different from any other Democrat. Hopefully, I am a little different—and I’m not being a wise guy.”

Whether Biden is seen as a wise guy or Obama’s designated white guy, there’s no dispute about the political import of the constituencies with which he has special purchase. With the Democratic ticket having established wide and apparently unbudgeable leads with African-Americans, Latinos, and Asians, the focus for Romney’s operation has narrowed almost exclusively to white voters. The performance with whites that will be required for Romney to win can be pinpointed with some precision, assuming that turnout levels of the other blocs are roughly the same as in 2008. “If the president is below 40 percent, like 38 or 39, there’s a chance for Romney,” says Republican pollster Bill McInturff, who with Democrat Peter Hart conducts the NBC/Wall Street Journal poll. “If Obama is at 41 or 42, it’s not going to work.”

Obama, recall, won 43 percent of the white vote in 2008, bolstered by his strength with college-educated white women, with whom he is doing even better this time. Thus the significance to Team Romney of two overlapping constituencies with which Obama is much weaker: blue-collar and silver-domed whites. And thus its recent emphasis on two issues meant to drive high turnout among those groups: welfare and Medicare. With a series of hard-edged ads, the campaign has put volatile issues of race and class squarely on the table, accusing Obama of gutting welfare reform and draining $716 billion from Medicare (and its mostly white recipients) to fund Obamacare (and its mostly minority beneficiaries). That the ads are either blatantly false or wildly misleading is largely beside the point, which is that they are effective. And that effectiveness, in turn, makes Biden’s role in vouching for Obama with working-class and older whites—the cops and firefighters and aging Catholics with whom his bond is, as he puts it, “sort of in my DNA”—all the more critical.

Yet Biden’s appeal is hardly limited to such voters. He is also a force with African-Americans and Hispanics. (His speeches this summer to the NAACP and the National Council of La Raza were both huge hits.) The secret sauce for Biden is his skill as fingertip politician: his gifts for gab, for glad-handing, backslapping, ear-bending, and good-natured arm-twisting. “There’s a genuine love of people and of the game,” says his longtime consultant John Marttila. “The only analogous figure in modern politics is Bill Clinton. You know that moment in Primary Colors where the Clinton character is in a Krispy Kreme at 2:30 in the morning talking to the guy behind the counter? If you want to understand Biden, you have to understand that’s where it starts.”

But if Biden’s facility for retail politics is, on the one hand, a glorious thing to behold, it makes him, on the other, a kind of anachronism. “He is always talking to the people in the room—that’s why he thinks he’s there, and he can never get to a place where that becomes secondary,” says another of his long-serving adjutants. “But the truth is, you’re really only in part talking to the people in the room; you’re also talking to, you know, everyone else.”

That would be true for any politician, but its meaning and implications are amplified a thousandfold for a sitting vice-president—as Biden, as he exits the Coffee Break Cafe, is about to be painfully reminded.

At the speech a few hours earlier that day at which Biden had coughed up “put y’all back in chains,” the comment had provoked no immediate commotion. The V.P.’s traveling press pack had fixated instead on another, more typical and less incendiary, verbal miscue: Biden’s fiery exhortation of the crowd, “With you, we can win North Carolina again!”—when, in fact, the stage on which he stood was in Danville, Virginia.

But by the time that Biden’s motorcade is rolling out of Stuart, the “chains” controversy is raging on Twitter, cable, and the web. In the traveling press van, a young network-TV producer is imploring Biden’s press secretary for a comment. “My bureau chief says it’s a big story,” the reporter explains. “I mean, it’s leading Drudge.”

Biden’s history of gaffes, of course, is long, storied, and infinitely entertaining. Just in his current job, he has made sport of John Roberts’s botched job in administering the oath of office to Obama (drawing the stink eye from the president); proclaimed in the midst of the swine-flu pandemic panic, “I would tell members of my family, and I have, I wouldn’t go anywhere in confined places right now”; referred to women lacrosse players as “gazelles,” to a Wisconsin custard-shop manager as a “smartass,” to a candidate for the House as a candidate for the Senate, to the Irish prime minister’s living mother as deceased, to the current century as the twentieth, to tea-party Republicans as “terrorists,” and to himself and Gabrielle Giffords as “both members of the Cracked Head Club”; made fun of Obama for his reliance on teleprompters; declared that “the president has a big stick”; and, the pièce de résistance, pronounced the passage of health-care reform “a big fucking deal.”

What accounts for Biden’s boners? The three prevailing conservative theories, that he’s a simpleton, or suffering senility, or both—don’t pass the laugh test. The people closest to Biden offer two alternative explanations, neither mutually exclusive nor unpersuasive.

The first involves Biden’s self-image as an orator of the highest rank. Though the V.P. relishes few things more than speaking, he detests prepared texts and the teleprompters that present them. He wants to add color, add texture, add flourishes—add the ad-lib. Combine that with Biden’s hunger to forge a tie with his audience, and what you get is him holding forth to a roomful of Virginians, straying off-script and slipping into a drawl, snapping off a one-liner easily misread, or misrepresented, as racially charged. As one of Biden’s aides observes, his error in Danville “wasn’t the chains, it was the y’all.”

The second boils down to Biden’s failure, even now, to reconcile himself completely to the constraints inherent in the vice-presidency. “Biden is adamant that part of his brand is saying exactly what he thinks, sometimes in exhaustive detail, about any issue,” says an adviser who has worked with him for years. “The biggest change psychologically he’s had to make is understanding that he’s no longer only speaking for Joe Biden. He’s speaking for Barack Obama, the administration, the whole Democratic Party. You’ll often hear him say, ‘Look, this is just my view, Joe Biden’s, not the administration’s or the president’s.’ We have to tell him, ‘You can’t say that.’ ”

All of which helps explain how Biden allowed himself to get ahead of Obama on same-sex marriage. The V.P. had recently been at a fund-raiser in Hollywood at the home of a gay couple and come away moved by meeting them and their two kids. So when he was asked about the topic on Meet the Press, the strictures of his office fell away: He had to speak his mind, tell the story, make it interesting. The V.P.’s aides could only sigh. Though they have no desire to quash his candor or spontaneity, they do wish they could imbue him with another quality: a smidgen of impulse control.

Biden’s moment of truth on gay marriage would have rattled the Richter scale in any era. But thanks to the insta-immediacy of the web and the infinite loopiness of YouTube, even his most trivial infelicities, inaccuracies, and imprecisions create unsettling tremors. The situation frustrates Biden, but he takes some comfort in knowing that the politician to whom he is most often compared has suffered similar travails.

“President Clinton and I had a talk awhile ago,” Biden tells me. “You know, there used to be in my generation a guy named Rod McLuhan”—here apparently mixing up Rod McKuen and Marshall McLuhan—“who said, ‘The medium is the message.’ And it really is kind of the message. So the discussion I had with Clinton was about how did he think he would have done on the rope lines [today], when everybody has a camera and a dictating machine, being able to instantaneously take three words out of a ten-word sentence and move it. We were both talking about how it generates a different kind of discourse and a campaign style … It’s like, the constituencies that I have strong and closest relationships with are not bloggers, you know what I mean?”

Certainly Chicago and the West Wing do. But after four years since Biden joined the ticket, his mistakes are fully priced into the stock. No one was doing cartwheels when “chains” chewed up several news cycles, and yet Team Obama treated it in just that way—as a cock-up, not a calamity.

“One thing you come to appreciate when you’re in these roles is that no one is gaffe-free—nobody,” Axelrod argues. “Every once in a while, that bluntness and ebullience of Biden’s skids off in a direction that makes you say, ‘I wonder what that was about?’ But in a business full of blow-dried automatons, he’s a vivid, authentic human being. He’s proven himself in really substantive ways, and he’s so good out there [on the campaign trail] that I’ll gladly take the downsides for the upsides.”

That the Obama high command will still feel the same way a week from now is all but guaranteed. Biden’s speech at the Democratic convention, taking place the same night as Obama’s in Charlotte’s Bank of America Stadium, will consist of “bragging on the president in a way the president can’t brag on himself,” in the words of one of Biden’s senior aides—and will likely set the proverbial barn ablaze. But the question of the V.P.’s ultimate impact won’t be settled until October 11, when he debates Ryan at Centre College in Danville, Kentucky.

The pressure on Biden that night will be plentiful, no doubt, with curiosity about Ryan likely to drive an unusually large audience for a veep debate. (“Our ratings should be better than Kemp-Gore,” quips Biden’s chief of staff, Bruce Reed.) But it will be nothing like what he faced four years ago. By the time that Biden finally went mano a mama grizzly with Palin, her disastrous interviews with Katie Couric had transformed her from a shooting star into a hick on a high wire. The challenge Biden confronted, therefore, was beating not just Palin but outsize expectations. And while Sarah from Alaska pulled off a Pyrrhic victory by not melting into a puddle on the floor, every post-debate instant poll judged Amtrak Joe the winner by a wide margin.

Taking on Ryan will be a more straightforward proposition. With Palin, the primary danger Biden had to guard against was appearing patronizing to her, seeming to dismiss her as a dim bulb—which he thought she was. “He had a real tightrope to walk,” recalls former Michigan governor Jennifer Granholm, who played Palin in debate prep with Biden. “We tried to goad him into being condescending, into showing off his Senate-speak. His instinct is to go on the attack, and he had to be careful there, too.”

The challenge this time is different. “Paul is, by everyone’s account and by my observation, a bright guy and is really ideologically driven,” Biden says. “So the difference is, I don’t think I’m going to have to worry that people are going to say, ‘There goes that guy pouncing on poor young Paul Ryan.’ ”

Quite the contrary. Among conservatives, the widespread assumption is that only one heavyweight will be present on the debate stage, and it won’t be Biden. That Ryan will show off his intellectual superiority—his policy wonkery, his mastery of matters budgetary—leaving the V.P. sputtering and flustered. And more than a few members of Biden’s own party fear that they are right. “There’s no secret about it,” a Democratic consultant observed to the Washington Post. “Ryan is going to school him.”

But this assessment underestimates Biden’s forensic savvy—and may well overstate Ryan’s. True, no one would ever nominate Joe for the chairmanship of Mensa (but then, the same should be said of any adult still enamored of Atlas Shrugged). His career, however, is replete with examples of assiduousness and applied intelligence. It’s often forgotten that it was Biden who, as Senate Judiciary Committee chair, masterminded the defeat of Robert Bork’s nomination to the Supreme Court. Also forgotten is how he did it: by huddling with legal scholars such as Harvard’s Laurence Tribe and determining that, although Bork’s strict-constructionist views on abortion were politically problematic, his positions on privacy more broadly were lethal. “Biden is a sponge,” says Granholm. “He’s a quick learner, a hard studier, a ferocious worker, and, most important, incredibly strategic.”

As for Romney’s running mate, Biden’s allies point out that, in his initial weeks on the ticket, Ryan’s armor has been shown to have a variety of glaring chinks: inconsistencies between his putative principles and his behavior on issues ranging from the stimulus to budget votes during the Bush administration. “You go down the list—Medicare Part D, the wars, the tax cuts,” says a prominent Democrat. “There will be a lot of ripe opportunities for Biden to expose Ryan for what he’s not.”

“I think this is going to be a values-driven debate, and on the values plane, there aren’t many people as steadfast as Joe,” adds his old friend and adviser Martilla. “Anybody who lowballs Biden in this setting is making a grave mistake.”

Biden, for his part, points to his experience as providing him a crucial insight that he will bring to bear against Ryan. “Ultimately, vice-presidential debates are about the president and the other nominee,” he says. “It’s all about the principal.”

What this means is that Biden has no intention of debating Ryan except as a proxy for Romney. Whether Ryan will be wise enough to understand the importance of doing the converse and adroit enough to act on it is an open question. His speech at the convention was proof that Ryan can turn on the charm and twist the blade when the red light comes on, at least in a scripted setting. What remains to be seen is if he can pull off the same tricks spontaneously and under fire, while at the same time projecting at least a facsimile of humanity.

“Ryan is better at that than Romney,” says Granholm, ignoring the fact that the same could be said about a mannequin. “But nobody is better than Biden. There are similarities between him and Ryan: both creatures of Washington, both know a lot about policy. But Biden understands what people are feeling and puts it into words, especially the anxiety of working people—no one feels their pain more than he does.”

On the last morning of his southern swing, Biden gives a speech (carefully, as written) at Virginia Tech university in Blacksburg, then makes an unscheduled stop at the memorial to victims of the 2007 shooting spree on campus. A misty rain is falling when he arrives at the site on the main quad. Slowly, silently, somberly, Biden walks along the semi-circular path, studying each of the 32 stones laid in the ground that bear the fallen students’ names, staring for a long time at the plaque that reads WE WILL PREVAIL. WE ARE VIRGINIA TECH.

As Biden makes his way back to his motorcade, a reporter asks what the memorial means to him. “It reminds you how precious life is,” he replies quietly, almost meditatively. “I think of those kids, but I also think of their parents. No child should predecease their parents. I remember what it’s like.” A long pause. “It brings back”—another pause—“it brings back memories. Whether it’s that call, out of the blue, that you get, and it’s like, How could this happen?”

For Biden, the call came nearly 40 years ago, a month after he was first elected to the Senate at the age of 29: A tractor-trailer had plowed into the family car, killing his wife and baby daughter and seriously injuring his two boys. Fifteen years later, Biden’s first campaign for the presidency ended in abject ignominy, with him branded a plagiarist (for lifting lines from Bobby Kennedy and the British Labour Party leader Neil Kinnock) and a fabricator (for false claims about his academic record in law school). A few months later, he suffered his two aneurysms and a pulmonary embolism, conditions so grave that a priest administered last rites. Twenty years after that, he waged his second presidential campaign, in which a gaffe on its announcement day—calling Obama “articulate and bright and clean”—grounded his bid before it took flight. In each of these instances, many people, and sometimes Biden himself, thought that he was finished. But it turned out Biden’s story always had another chapter in it.

The question swirling around the V.P. now is whether he is ready to acquiesce to his epilogue—or might try to generate a whole new volume. In 2008, the premise of Biden’s selection as running mate was that he was a Cheney pick: He would serve Obama free of ulterior motives or longer-range ambitions. But almost as soon as Biden assumed office, his people put out the word that, as his then–communications director Jay Carney was quoted saying in the Times, “we’re not ruling anything in or out” regarding 2016. Since then, there have been routine emanations from Bidenworld that the idea of another run is on the table.

“I’ll give you my word as a Biden—a serious answer,” the vice-president says when I raise the topic on Air Force Two. “If the Lord Almighty came down and sat at that coffee table and said, ‘I guarantee you’re the nominee if you say yes now,’ I wouldn’t say yes now. Because I don’t know what the hell four years from now, three years from now, is gonna be like. But I know one thing: I have no intention, if I feel as good and have the same mind-set I have today, of my just saying, ‘Well, you know, I put my years in, and I am proud of what I did. And now, you know, I’m going to play a lot more golf.’ ”

So just how serious is the prospect of Biden 2016? According to his lieutenants, the floating of the possibility is partly a hard-eyed effort to maintain his currency and leverage; Biden is fond of saying, “You’re either on the way up or on your way down.” But Biden also genuinely wants to keep the option open. What’s animating him at this point is less calculation than ego, pride, and force of habit. “You go to someone who’s been a senator since he was 30 and say, ‘That’s it, you’re done,’ ” postulates one of his closest confidants. “What’s he going to say? ‘You’re right, thanks!’ No. He says, ‘What do you mean I’m done?’ ”

For all of Biden’s impetuousness, however, he is also a pragmatist, and one who relies to an unusual degree on a particular (and particularly vivid) brand of foresight. As Air Force Two touches down at Andrews Air Force Base, Biden is musing about What It Takes, Richard Ben Cramer’s classic book about the 1988 campaign. “He came up for each one of [the characters in the book] with one little thing that he said was the defining feature of who we were,” Biden says. “And with me … it was that I’ve never done anything, except once in my life, that I couldn’t see [in my mind beforehand]. When I’d go out for a pass, I would literally picture the ball in my hands before it was thrown. That’s how I do things. I picture exactly what the end is gonna be. Jumping out of a tree on top of a trolley car as a kid, I’d picture it. It wasn’t just impulse. And when he said that, I started thinking to myself, Son of a bitch. How did he … ?”

All of which explains why Biden, as far as I can tell, is actually, factually undecided about 2016. There are simply too many unknowables for him to be able to form a clear picture in his head of his own future. Will the economy turn around? If it continues to flatline, the Democratic nomination in 2016 will be close to worthless for anybody, let alone Obama’s two-term No. 2. Will Hillary Clinton run? If she does, Biden’s close friendship with her—and his desire not to end his career being flattened by the political equivalent of a freight train—would almost certainly impel him to stand down.

Yet Biden can already see one thing clearly, which is the foundational and nonnegotiable precondition to hurling himself at the White House again: he and Obama on Election Day, victorious. Or so he tells me.

“Here’s where I am,” he says as we prepare to part. “I really don’t see how the American people embrace a team that says, ‘There’s really no compromise. It’s my way or the highway.’ And secondly, how they embrace the notion that we’re gonna cut a whole lot of things in order to spend, even if they get tax cuts, billions of dollars on people who aren’t even asking for it.”

Biden smiles, pats my shoulder. “That’s what this campaign’s about,” he concludes. “And if I’m wrong about this, then I … I … I … I … I really should retire retire.”

Additional reporting by Clint Rainey.