|

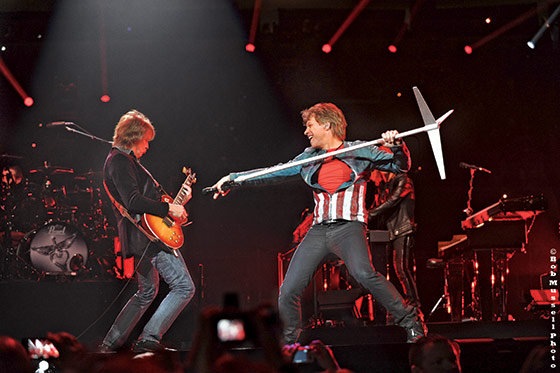

The last time Jon Bon Jovi played Buffalo (to cheers), in 2013.

(Photo: Bob Mussell) |

And so, the ban. Several fans from Orchard Park, home to the Bills’ stadium, formed a group, now known as Bills Fan Thunder (originally called the 12th Man Thunder), and began handing out BON JOVI–FREE ZONE posters to local businesses. Jack FM 92.9 announced it would replace the 13 Bon Jovi songs in its rotation with a revised version of “Livin’ on a Prayer.” (“Johnny used to get played on Jack / Now he wants our Bills / But Buffalo just won’t take that / He’s wack.”) Slippery When Wet was banned not just from participating bars, but also from CrossFit gyms, strip clubs, a local Moose Lodge, and Lullabies and Butterflies Family Daycare. “He won’t be wanted dead or alive,” read a comment on the group’s Facebook page. “He will be dead.”

Buffalo is New York State’s second-largest city, but it’s closer to Cleveland and Detroit, both geographically and spiritually, than to Manhattan or Brooklyn. In 1901, when the city hosted the Pan-American Exposition, Buffalo was America’s eighth-largest city, with more millionaires per capita than anywhere else in the country. By 1960, when the Bills came to town, it was still among the top 20 largest cities. Today, it is 73rd. The city had built its reputation on moving things better than anyone else, but the mid-century construction of the interstate-highway system and the dredging of the St. Lawrence Seaway, which made possible oceangoing traffic from the Atlantic all the way to Chicago, had shoved Buffalo to the sidelines of the modern transportation economy. “This city’s primary export is young people,” said Mike Caputo, a Buffalo native and PR consultant for the Bills Fan Thunder.

And yet most Buffalonians maintain an intense pride in their city—they like to point out that their football team is the only one that plays its home games in New York State—and when I visited the city earlier this month, Matt Sabuda and Brian Cinelli, co-founders of the Buffalo Fan Alliance, another Bills fan group, tasked themselves with showing me the city’s optimistic side. The metro area’s population had ticked upward after six decades of decline, and cranes were visible on the skyline for the first time most people could remember, thanks to $1 billion in extra state funds allocated for its economic development by Governor Cuomo. “The momentum is finally shifting for an area that has really struggled,” Sabuda said as we sat down at a bar on Lake Erie that could have been on the North Fork if the assembled yachts were bigger. “If the Bills left, it would be like the guy who starts being really successful—he got the great job, he bought the awesome house—and the wife just says, ‘I’m out.’ ” I heard the broken-marriage analogy from a number of Buffalonians—most of the time followed by an addendum noting that they would rather have her run off to Los Angeles with the guy in the red convertible than with a friend 90 minutes away. “With Toronto, it’s like she’s leaving him for his neighbor,” Sabuda said.

By the time I arrived in Buffalo, the anti–Bon Jovi movement had developed multiple fronts: If the Bills Fan Thunder are its rank and file, Sabuda and Cinelli, who both hooked their sunglasses onto the third button of their collared shirts, are its diplomats. (Most of the people involved in both movements are middle-aged white men.) When Ralph Wilson’s health began to decline, Sabuda, a real-estate investor, and Cinelli, a lawyer, had looked into various ways they might keep the team in town—public ownership, antitrust claims, suing the NFL—before settling on a plan to raise a pool of money from local businesses, fans, and concerned citizens that could be offered as an interest-free loan to an owner committed to Buffalo.

Sabuda and Cinelli had not yet raised any of the $100 million they hoped to gin up, but they had recruited several prominent former Bills to join the group’s advisory board and were planning to meet that afternoon at a casino in Niagara Falls with Andre Reed, a retired wide receiver. As we drove north along the Niagara River on the Robert Moses State Parkway—“Robert Moses built highways on all of our best views,” Sabuda said—they ticked off a list of natives who might save the team: Terry Pegula, who owned the NHL’s Sabres, or Tom Golisano, who made a fortune creating payroll systems but had said he wouldn’t get into a bidding war with the Toronto group.

“What about that guy from Google?” Cinelli asked.

“Chris Sacca?” Sabuda said. “He was an early investor in Twitter. He tweets about the Bills all the time.” (Sacca’s tweeting had not yet turned into an interest in buying the team.)