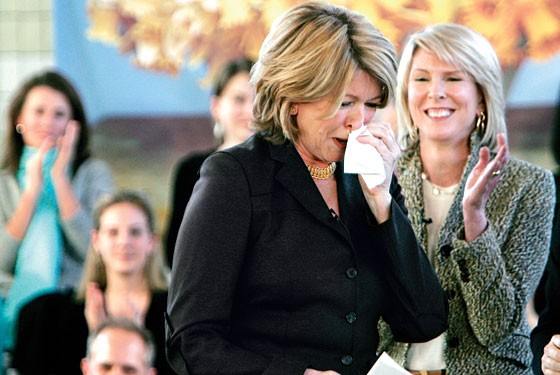

She wore a brown suit hemmed at the knee, a gold necklace, and stiletto heels. As she walked into the soaring white hall with clerestory windows, hundreds of her employees rose from banks of folding chairs, clapping and cheering.

It was the morning of Monday, March 7, 2005. Three days earlier, Martha Stewart had been inmate 55170-054, patron saint of precipitous falls. After news broke in June 2002 that Stewart was being investigated for insider trading, her company stock plummeted; since she owned a majority of the shares, this meant that her own net worth was also devastated. She had been ousted from control of the company that bore her name and seen its very existence threatened. She had been pilloried in the tabloids, humiliated in the courts, and locked up in prison for five months.

She was 63 years old, an age when many people are finalizing plans for their retirement. Instead, returning to the West Chelsea offices of Martha Stewart Living Omnimedia, Stewart looked poised to launch one of the all-time great comebacks in business history. As the theme music from her TV show played, she blew kisses and stepped onto a stage in the middle of the room.

While incarcerated, Stewart had transformed her public image. At the federal women’s camp in Alderson, West Virginia, she had taught yoga, picked wild dandelion greens, and learned to appreciate the simple virtues of vending-machine chicken wings. Now, standing beside a spray of daffodils, Stewart told her employees she had thought of them every day. They were her heroes, she said. She held up the nubby, scallop-edged poncho crocheted by a fellow inmate that she had worn as she flew home from Appalachia in a Dassault Falcon jet. She spoke of the “tremendous privilege” of meeting the women with whom she served time at the facility. “I don’t regret everything,” she said.

Stewart’s company had not left the stagecraft of her resurrection to chance. At her Cantitoe Corners farm in Bedford, a flatbed truck was provided to give the media an optimal vantage to document her return home. And already, Martha Stewart Living Omnimedia seemed well on its way to repairing the destruction of the past three years. An estimable new CEO, Susan Lyne, former president of ABC Entertainment, had been appointed. The company had signed a high-profile deal with producer Mark Burnett to put Stewart back on TV, both in her daily show and in a new, Martha-focused version of The Apprentice. Soon, she would resume her column in Martha Stewart Living.

Wall Street had taken note. From the moment the previous September when Stewart announced that she would begin her prison sentence immediately—she wanted to be out in time to oversee the spring planting in Bedford—until shortly before she was released, MSLO stock rose from $11 to $36. Stewart’s personal net worth more than tripled, to over $1 billion, and she was named to the Forbes 400 list for the first time.

And so, as she spoke to her employees that Monday morning, it was possible for Stewart and her team to disregard the recent past and even the near future, when for five months she would wear a monitoring anklet and be confined to house detention for all but 48 hours of the week. “We are, all of us, in this next chapter, going for greatness,” Stewart said, before growing misty.

As part of a settlement with the Securities and Exchange Commission, Stewart later consented to a five-year ban from serving as an officer or director of her company. Next month, that ban comes to an end, and with it, so does the saga of her misbegotten stock trade. Stewart will rejoin her board of directors this fall. But the Martha Stewart Living Omnimedia of today bears scant resemblance to the one she imagined six years ago. In fact, the prevailing narrative of Stewart’s post-prison years, according to which she redeemed herself and overcame her tribulations, is largely illusory.

MSLO has been profitable in only one of the past eight years, losing a total of $185 million during the same period. In the fourth quarter of last year, on the verge of violating loan covenants, the company had to renegotiate its debt with Bank of America. Operationally, the company faces significant problems, too. Stewart’s daily television-programming block on the Hallmark Channel has scored such disappointing ratings that it was cut from eight hours to five. The company has struggled to replace the revenue it used to enjoy through its licensing partnership with Kmart, and it has failed altogether to build a commercially significant digital business. Its stock price has languished below $5 for most of the past year (and at press time was $4.07). Last week, a Wall Street analyst slashed his valuation of the company’s assets by 10 percent.

MSLO recently announced that it had retained the Blackstone Group to “explore strategic partnerships.” Many analysts interpreted the move as the first step toward a possible sale. This past Friday, Stewart’s top executive announced he would step down a year ahead of schedule. The idea of Stewart selling the company that embodies her life’s work seems almost unfathomable. In fact, it’s difficult to say which would be more unlikely: Stewart relinquishing her company completely, or Stewart reporting to other owners. But she may have a powerful incentive to sell. Her wealth is overwhelmingly tied up in her stock, which is both depressed and illiquid; an acquisition could provide a cash windfall. She also may have little choice. Given the straits in which the company finds itself, her board may see no alternative.

Though people close to the company were reluctant to speak on the record, they tell a remarkably similar story of how things reached this point. Following her June 2003 indictment for charges surrounding her suspect trade of the biotech stock ImClone Systems, Stewart had watched her control over her company disintegrate. The board of directors, which she had kept out of the loop about the SEC’s interest in her stock trade until after it had become a full-fledged problem, had cautioned her about the risk of denying everything. If she disgorged her profits, admitted to a faulty memory, and showed some humility, she would likely get off with a slap on the wrist. But Stewart, who declined to be interviewed for this article, had been determined to maintain her innocence. “No amount of advice could dissuade her,” recalls someone knowledgeable about Stewart’s conversations with the board.

Upon being indicted, Stewart had stepped down as chairman and CEO, and with the company losing advertisers and business partners en masse (Safeway pulled out of a significant planned licensing deal), the board had quickly embarked on a de-Martha-ing strategy: shrinking her name on the cover of the magazine, and removing it altogether from Everyday Food (an unfussy magazine the company had launched to hold the line against Real Simple). The company’s attempts at diversifying included acquiring the newsletter of alternative-health guru Andrew Weil and the magazine Body & Soul. It also began to develop new personalities from within, including Marc Morrone on pets and Lucinda Scala Quinn as a more approachable food brand.

De-Martha-ing, not surprisingly, did not sit well with Martha. But by this point, her influence over the board was minuscule, and a number of directors who had joined what they thought would be a board “about fun and eating cookies,” as a colleague recalls, were replaced. On the advice of counsel, the board largely ceased communicating with Stewart. When she asked that the company pay all her legal expenses, on the grounds that what was good for her was good for the business, the board refused. “She said, ‘I am the company. Without me, the company’s nothing,’ ” says someone familiar with the matter. “It was a very emotional conversation.”

Jeffrey Ubben, the then-chairman of her board whose investment fund had taken a 20 percent stake in the company, had believed that she was being scapegoated. Still, he also felt a fiduciary duty to his investors. “I spent a lot of time personally trying to get her to put it behind her,” Ubben says. “As awful and unfair as it was, if she went to jail and paid penance and came back strong, that was the way to get through it. That was a terrible conversation.”

It had been perhaps the most destabilizing episode in Stewart’s life—the moment when she felt least in control of Martha Stewart Living Omnimedia. But it also marked the beginning of her attempts to take it back. Because when Stewart finally agreed to begin her sentence, she had asked for something in return.

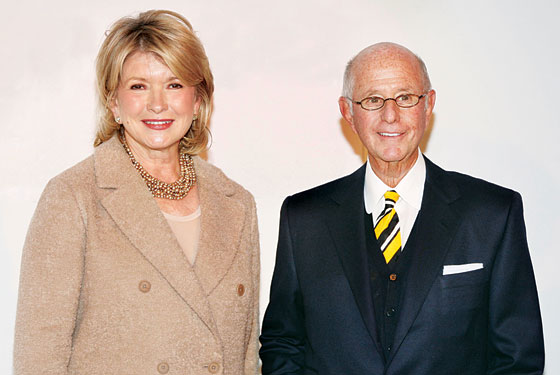

In March of 2004, a week after her conviction, Stewart joined her friend and personal banker Jane Heller, of Bank of America, for lunch at the Long Island home of Charles Koppelman, former CEO of EMI Music. In recent years, Koppelman had developed a specialty advising celebrities in trouble. When designer Steve Madden went to prison for securities fraud, Koppelman took over the company in his absence, and Heller, who was both Koppelman’s and Michael Jackson’s banker, had insisted that Jackson hire Koppelman as an adviser. At a moment when Stewart had been frozen out by her board, a former director says, “he told her, ‘I’ll help you get the company back.’ ” Koppelman would later tell Fortune that he had told Stewart “there would be circumstances where what’s good for Martha Stewart isn’t good for the company. But what’s good for her company is 100 percent certainly good for Martha Stewart.”

Koppelman understood the needs of artists and celebrities. He told Stewart just how misguided he thought the de-Martha-ing strategy was. She was grateful to find someone who understood how underappreciated she and her brand were. It was a strange merger of sensibilities: The doyenne of baking and fresh linens was aligning herself with a cigar-smoking macher of business deals and pop-music hits (Vanilla Ice, Wilson Phillips) whom she had only just met. But with striking speed, Koppelman, who declined to comment on the record for this article, became Stewart’s confidant.

Stewart recommended Koppelman to the board twice. At first, in June 2004, the board voted not to appoint him, out of concern that he would be a mouthpiece for Stewart, and because of his reputation from his time in the music industry. Off the Charts, Bruce Haring’s exposé of the industry in the nineties, depicts Koppelman as a spendthrift who chased hits at the expense of building artists’ careers. But one month later, after agreeing to go to prison, Stewart again asked that Koppelman be named to the board. This time, the board acquiesced. According to several sources, Arthur Martinez, the board’s deeply experienced lead director who was former CEO of Sears, resigned the same day in protest.

The new, softer Martha Stewart who emerged from prison allowed microwave ovens to be referred to in her magazines for the first time. She named one of her French bulldogs Francesca, after a fellow convict. She announced plans to do a TV show about rehabilitating errant women while they rehabilitated a house; a fixer-upper was bought in Norwalk.

That show never happened (among other reasons, Stewart’s probation forbade her to associate with felons), but otherwise, Martha Stewart Living Omnimedia became a deal-making machine. Besides the Burnett TV deal, there were a series of how-to DVDs to be distributed by Warner Home Video; an all-Martha-all-the-time satellite-radio channel on Sirius XM; a business book called The Martha Rules; and a licensing agreement under which KB Home would develop whole communities of Martha-designed and –branded houses. MSLO made plans for a magazine targeted at younger readers called Blueprint, which would launch in 2006.

This burst of activity was a strategic plan to save MSLO from extinction, but it soon seemed to some observers within the company as if Stewart’s attitude had less to do with business prudence than with an urgent desire to make up for the years she had lost. “There were things she was more willing to consider” than previously, says a former board member. Some of the deals were misconceived. Her Apprentice was “a debacle,” in the words of a television executive close to the deal. “Mark Burnett was all about controversy,” says the executive. “He wanted to say the word jail. He wanted her to show the house-arrest bracelet. Frankly, Martha’s about making apple pie.” In 2005, the company lost $76 million.

By the end of that year, it was evident that the humility Stewart had acquired during her legal troubles was not so easy to maintain. In interviews, she stopped talking about the poncho and Francesca the convict and jailhouse yoga and became increasingly confident. In an article in Fortune, she declared her big takeaway from the ordeal to have been: “I really cannot be destroyed.”

Stewart was supported by a tight new circle of advisers. Sharon Patrick, the former McKinsey consultant who had been the co-architect of her business empire, was gone, having served as CEO after Stewart’s indictment until being replaced seventeen months later by Susan Lyne. Patrick lacked a chief executive’s temperament, in the view of the board, but her absence was quickly felt: Because of her feisty personality and long relationship with Stewart, Patrick was seen as having a unique ability to stand up to her.

Koppelman became chairman in 2005, and he began to take an increasingly hands-on role at the company. He was a canny, Brooklyn-born businessman who, while still in college, had managed to land a record deal for his singing trio the Ivy Three. Though some of the deals he would make for the company were invaluable—Sirius XM and Home Depot, to name two—he could be an irritant to the rest of the corporate leadership, partly because of his own deal with MSLO (when he first joined the board, he negotiated a paid consulting arrangement for himself) and partly for more stylistic reasons (he had the computer removed from his office to make room for a TV). Koppelman was also viewed as enabling Stewart’s self-regard as much as tending to the company’s well-being. “He told her the stock should be at $30,” an executive recalls. “I asked him, ‘What’s your math?’ He’d call me negative.”

There was unusually high executive churn, and according to many executives who worked there, it was an intensely frustrating environment in which to get things done. Robin Marino, the head of merchandising until this May, was responsible for 3,000 items at Macy’s alone, but Stewart insisted on personally approving every one. “At a board meeting,” recalls someone with knowledge of the episode, “Martha walked in with a pot, slammed it on the table, and goes, ‘This is crap. I don’t want my name on it.’ ” A series of highly capable executives came and went, worn down by Stewart and thwarted in their efforts to bring the company back to health. And yet, although Stewart’s reputation of being a difficult boss was widely known, she continued to attract talented executives. Explains one: “Before you go there, you can’t imagine how bad it is. You can’t imagine that a company with a brand that’s so big could keep functioning with so much dysfunction.”

As if the company didn’t have enough challenges, it was facing a massive threat to its bottom line. The Kmart deal Stewart had forged in the late nineties was singularly brilliant. At the time, Kmart was desperate, and she had exacted a lopsided contract that guaranteed an escalating minimum payment to MSLO every year, regardless of how many products Kmart was selling.

When Kmart went into bankruptcy in 2002 and began shutting down hundreds of stores, it became that much harder for the retailer to sell enough products to meet the minimums. After Sears and its hard-nosed chairman, Eddie Lampert, took over Kmart, and the deal came up for renewal, they were firm in demanding a more equitable agreement. Watching Stewart and Lampert negotiating, a former Kmart executive says, was “like a cockfight; both of them were arching their backs and making points that weren’t really relevant.”

The deal was not renewed. This became a huge problem for Stewart. By 2005, Martha Stewart Living Omnimedia, despite its name, had morphed from a media company into a merchandising company. That year, the merchandising division was the only one that made money, and 89 percent of it came from the Kmart deal. In 2007, the company was profitable for the first time since 2002, but that performance was significantly helped by one of the largest payments in the Kmart contract. With the deal’s end approaching in January 2010, MSLO desperately needed something to replace it.

At times, the offices resembled a shelter for battered crafters.

The board had long been concerned by what even Stewart called the “getting hit by the bus” scenario. For all of the brand’s ubiquity, the business was strikingly undiversified beyond products that had Stewart’s name on them. One model the directors had looked to was the Estée Lauder Companies. As Estée approached 70, the company began to acquire other brands and also launch its own non-Lauder brands, such as Clinique. Smart acquisitions, theoretically, could help make up the revenue gap expected with the end of the Kmart deal.

Stewart proved resistant. There were a few small successes, like Everyday Food, and the purchase of Emeril Lagasse’s non-restaurant-business assets. But many more attempts to diversify went nowhere. The company pursued a series of potential acquisitions, including the Knot, Cynthia Rowley, and Jonathan Adler. A lot of the deals were far along, and then Stewart would find something wrong with them. In some cases, she’d nix the idea at the last minute, after sitting down with the prospective brand owner. As one former executive puts it, “She didn’t want anyone else in the kitchen.”

Instead, the company went into a merchandising frenzy. When Sharon Patrick was around, she had enforced a careful discipline on outside deals, making sure they were both true to the brand and significantly profitable. The new licensing relationship with Macy’s, which began in 2006, has since proved integral to MSLO’s merchandising business, as have partnerships with Home Depot, PetSmart, and the crafts retailer Michaels. The board, according to an ex-member, squelched many of Koppelman’s ideas, including attempts to do a deal for Martha-branded vitamin supplements and Martha-branded clothing. They were also opposed to a deal with TurboChef, which wanted to bring out a Stewart-branded $6,000 convection oven. “It was exactly the opposite of what we preached,” this person says, “which was that we didn’t just put our names on things—we create things.” But the deal, which included a multi-million-dollar first-year license fee, eventually went through. By last year, the company had done a hodgepodge of licensing deals, including video games, a wine with Gallo, branded weddings at Sandals Resorts, and frozen dinners at Costco.

The company’s looming revenue problems—and its sinking stock price—affected Stewart’s mood, and the mood was infectious. The creative rank and file at Martha Stewart Living Omnimedia were a mix of proud elitists and wild enthusiasts, prone to almost ecstatic fervor about such matters as glitter and hole punches. They lived for Martha’s approval, and at her best, she could be inspiring. But Stewart was also famous for her drive-bys. A group of stylists and art directors might spend a week away on a shoot, only to have Stewart dismiss their labor with a belittling remark. “Martha would say, ‘Ugh, why are there bananas there? I hate bananas,’ ” says someone who edited food stories. “There’s a list of things she loathes.” At times, the offices resembled a shelter for battered crafters. “That women’s bathroom,” the editor adds, “there are women in there crying literally all day long.”

Stewart had invented the category of lifestyle publishing and branding, but by 2008, she had a lot of younger, leaner rivals. Plus, the recessionary economy of the late aughts was far removed from the bubbly millennial environment in which Martha Stewart Living Omnimedia had gone public, and what had thrived as an aspirational brand at times seemed out of touch.

At the flagship magazine, Martha Stewart Living, one editor after another would come in and try to Real Simplify it, to make it more about hamburgers and chocolate-chip cookies and less about tassel-strewn, Venetian-themed dinners for twenty. A Thanksgiving story shot at Stewart’s stables in Bedford featured a long table and was so complicated that it became almost a comedy of errors. A child’s hair caught fire. Stewart sliced her thumb and was sent to the hospital. At the table, Stewart was flanked by Brooke Astor’s son, Anthony Marshall, and his wife, hardly avatars of the simple life. (By the time the story was published, Marshall was on trial for misappropriating his mother’s fortune, and the pictures had to be blurred out.) “There was an incredible divide between what Martha was interested in and what the reader wanted,” a then-editor says. “As Martha got fancier, readers were going in the other direction.”

In the boom years, Stewart’s extravagances could reasonably be seen as the cost of doing business. But with MSLO losing money, the clash between business imperatives and Stewart’s perfectionist aesthetic became increasingly problematic. “The entire workday would come to a halt so we could discuss the virtues of sea-foam green over more of a blue-green, and would take literally 30 minutes,” remembers an editor. “Susan [Lyne] would say, ‘I’m sure you guys can make this decision.’ ” Despite the cash crunch, Stewart would not hesitate to send staff members to, say, India, to obtain a certain piece of fabric. The company kept three separate test kitchens. Stewart herself retained “nine personal assistants,” says a former executive. “Nine. That number is untouchable. I broached it with her, and I almost lost my job that day.” (A source close to the company calls the number “highly exaggerated.”)

Part of the disconnect had to do with the fact that Stewart’s own lifestyle was becoming more luxurious. In 2008, shortly before Lyne left as CEO, Stewart asked the two board members seen as being most assertive in challenging her compensation and expenses to resign. At the same time, the Koppelman-led board replaced Lyne with two co-CEOs, a structure that observers noted left Koppelman, who assumed the titles of executive chairman and principal executive officer, firmly in control. Since then, the board has changed from one dominated by seasoned corporate executives with diverse board experience to one liberally salted with friends. (Frédéric Fekkai, Stewart’s former hairdresser, sits on the compensation committee.) Stewart’s annual compensation package grew from $2 million in 2007 to $10 million in 2009. That year, Stewart also received a $3 million onetime “retention” and “noncompete” payment, preventing her from leaving her own company and competing against it. Koppelman, in 2008, received $8 million in compensation.

There was also the matter of Stewart’s personal expenses—long the subject of titanic struggles between her and her CFOs. It has never been clear where Martha Stewart the person ends and Martha Stewart the brand begins, nor how either is distinct from Martha Stewart Living Omnimedia. She lives and breathes her business and anything she does (or buys) in her personal life can become fodder for the magazine, or the TV show, or a product, or a tweet. But between her farm in Bedford, her home in Maine (Skylands, the former Edsel Ford estate), a house in East Hampton, and an apartment on Fifth Avenue, Stewart has steep personal bills to pay. And that isn’t including her car and driver, personal trainer, home-security system, and other amenities that come with being Martha Stewart. She expenses an extraordinary amount of them.

The company’s porous boundary between personal and professional extended to other personnel. Koppelman hired his daughter, Jennifer Koppelman Hutt, to be his assistant, and later she became co-host, with Stewart’s daughter, Alexis, of the television show Whatever, Martha! Koppelman Hutt was paid $350,000 last year, while Alexis Stewart made $400,000. Koppelman’s fiancée, Gerri Kyhill, who had been his late wife’s manicurist before becoming his assistant, runs the New York outlet of the pole-dancing-exercise chain S Factor, in which Koppelman is an investor. In 2008, MSLO’s human-resources department sent an e-mail to employees offering pole-dancing classes at S Factor as a company-paid benefit. Kyhill and S Factor’s founder, Sheila Kelley, also led Stewart through a pole-dancing routine on her television show.

The outsize compensation, the board’s composition, the aggressive expensing—this is exactly the kind of corporate governance that can depress a stock. James Berman of hedge fund JBGlobal put 10 percent of the fund into shorting MSLO from September 2009 to June 2010. He was drawn to it because of the company’s “excessive compensation and ‘related-party transactions,’ ” among other apparent conflicts of interest, and successfully rode the stock down from $7 to $5. “It’s one of the few successful shorts we’ve had during this bull market,” he says.

Wall Street was punishing Stewart for not putting stockholders’ interests first. But she wasn’t even putting her own interests first. Stewart’s wealth is tied up almost entirely in her real estate and company stock, which she has always believed to be undervalued. One of the intriguing aspects of her high compensation is that if she were simply to take a $1 salary, along the lines of Steve Jobs, the market would almost certainly reward the move with a hike in her stock price; and an increase of just $1 would boost Stewart’s net worth by tens of millions of dollars.

Multiple former executives see this as Stewart at her least rational. One of them speculates that she can’t help feeling, given how hard she works, that she deserves to be paid well. Another executive chalks up Stewart’s obsession with compensation to her humble origins: “I think she still has the fear that she will end up with nothing.” This was the billionaire, after all, who had risked everything over a $51,000 stock trade.

Even using the loosest definition of “business expense,” Stewart has found she cannot fund her lifestyle on reimbursements alone. In recent years, according to a knowledgeable source, her old friend and personal banker Jane Heller has arranged extensive loans to Stewart. When it was announced in May that Blackstone had been retained, one theory was that Stewart “needs an event to monetize her stake.”

As the stock price has continued to disappoint, sinking as low as $1.73 in early 2009, sources say that relations between Stewart and Koppelman cooled. Stewart has always looked outward when apportioning blame, and she seems to have settled on Koppelman, her onetime savior, as the responsible party for the company’s poor performance. “Martha doesn’t like to hear what she doesn’t want to hear,” someone with knowledge of the relationship says. “Even Charles knows things are beyond screwed-up. He’s become the bad guy.”

This week, Martha Stewart will turn 70. The former model still looks remarkably youthful. She remains ever interested in learning something new and traveling to an exotic place she hasn’t been before. She is a gadget geek who’s constantly tweeting her own photographs (“She’s like a middle-aged man when it comes to audiovisual equipment,” says a middle-aged man who has worked with her). But although she has borne her age gamely, the fit with her brand has become slightly strained.

Stewart had explored launching a magazine targeting older readers that was to be called Grace (her confirmation name), but after Blueprint folded in late 2007, the project was shelved. The pole-dancing video is a little bit painful to watch. And the incorporation of Alexis Stewart into the company fold has been a study in brand dissonance, with the daughter of the woman who likes to talk about her Friesian horses free-associating on-air about her abortion and her sexual fantasies involving Scott Bakula.

Several people who’ve worked at her magazines say that Stewart has become less certain that she is in touch with younger people’s tastes. Thus the rise of 42-year-old decorating editorial director Kevin Sharkey, a kind of adoptive son to Stewart who often travels with her. She’s named a shade of gray in her line of Home Depot paints after him, as well one of her French bulldogs.

Of course, Stewart is still Stewart. This was apparent even in the Blackstone announcement, which used the unusual phrase “explore strategic partnerships.” Because the typical code for putting a company on the block is “explore strategic alternatives,” the wording suggested that MSLO was not in play and yet might be. There are any number of reasons why a company might not wish to telegraph a determination to find a buyer. A motivated seller draws lowball offers. But in the upside-down universe of Martha Stewart Living Omnimedia, there may be stranger reasons for the cloudy phrasing. “My belief,” says an MSLO insider, “is that Martha does not want to be perceived as someone who wants to sell the company, so if it doesn’t sell, it won’t be perceived as a failure.” More weirdly, an institutional schizophrenia may be playing out, where the board wants to sell the company and Stewart doesn’t. Indeed, no sooner had the press release gone out than new COO Lisa Gersh went off-message, telling the New York Post, “It is not our stated intention to sell in any way.”

The company does have significant assets. For all its travails, it has proved able to innovate, creating iPad apps successful enough that Apple and Adobe use them in their ads; Stewart has 2.3 million Twitter followers. The Martha Stewart brand remains hugely iconic. The company has a vast library of evergreen how-to content that can be repurposed for years to come. Its major merchandising partnerships are growing, and last week, on the company’s lackluster second-quarter earnings call, Koppelman sketched a future of robust international growth.

Analysts and sources knowledgeable about MSLO suggest a range of possible outcomes. In one, the company goes private, freeing it from the burdensome costs, responsibilities, and scrutiny of being a public corporation. This scenario, according to a source close to Stewart’s camp, is the one favored by Stewart: It would allow her to partially cash out while giving her more control of her company. According to another source, Blackstone has been engaged for the dual purpose of first positioning the company for sale—by signing up for a number of new licensing deals—and only then selling it. The great new hope at the company is Gersh, a sharp-elbowed television executive who is expected to ascend to CEO. That ascension drew suddenly nearer when it was announced last week that Koppelman will step down from his executive position by December, a year earlier than his contract had provided. Yet if Gersh has been hired to make some of the tough cost cuts Stewart has long resisted, it’s an open question how long she will remain in Stewart’s good graces once she tells her that she needs to cut the budget of, say, Martha Stewart Living, by 30 percent.

Because of Stewart’s propensity to hold so tightly to her brand and empire and prerogatives, she now faces an unenviable conundrum: She must be torn between her reluctance to give up power and her desire for her company—and name—to outlast her. Were she only to fade gracefully into an emeritus role, she might sit back and watch her stock rise. But that would require that she get out of her own way.