Collins Tuohy has told this story before, and by now her delivery is spot on. It was Thanksgiving morning, and her family were on their way to pick up breakfast. “Because in our household,” she says in her Memphis drawl, and pauses for emphasis. “My mother thinks that if we go and get food.” Dramatic pause. “And bring it back to our house.” Another pause. “Then it counts as home cooking.”

The audience laughs as Collins, a twentysomething Kappa Delta in a leopard-print dress and heels that bring her a good four inches closer to God, shakes her head affectionately at her parents, Leigh Anne and Sean, who are sitting next to her onstage at the Aria Resort & Casino in Las Vegas. Then her story turns serious. As they were driving, they spotted a boy from Collins’s school walking down the street, unseasonably clad in shorts and a T-shirt. Leigh Anne asked her husband to pull over.

You probably know the rest. So did the thousand or so salespeople that diamond manufacturer Hearts on Fire had invited to hear the Tuohys speak during its annual seminar. At this point, practically everyone with eyes has seen the movie The Blind Side, which tells the story of how the Tuohys adopted that boy, Michael Oher, and transformed him, by the grace of Jesus and with the help of cash from Sean’s fast-food franchises, from almost-certain lost cause to millionaire NFL star.

Oher’s story might never have been told outside Memphis if Sean Tuohy’s high-school classmate Michael Lewis hadn’t happened into town soon after that Thanksgiving Day to talk to his old friend for a story he was working on about their high-school baseball coach. Lewis watched as Collins, her brother, Sean Junior, and a six-foot-four, 350-pound mystery streamed in and out of the house and quietly wondered what the hell was going on.

When they were done talking, Sean Tuohy escorted Lewis to the door. “Well, I hope another 25 years doesn’t go by,” he said.

Lewis paused in the entryway. “You’re really going to let me out of here without telling me who the black kid is?” he asked.

Collins Tuohy hasn’t actually read the book that Lewis subsequently wrote about her family and that served as the basis of the movie. She doesn’t need to, she says, and not just because she “lived it,” as she puts it, but because the story has taken on a life of its own. Last year, the Tuohys published another book, In a Heartbeat: Sharing the Power of Cheerful Giving, followed in February by Oher’s own memoir, I Beat the Odds. Leigh Anne, who was an interior decorator before she became professionally herself, has appeared on Extreme Makeover: Home Edition, is developing a reality show about at-risk children, and has become good friends with Sandra Bullock, who played her in the movie. “I could eat him with a spoon,” she told People, of the actress’s own recently adopted child.

“But it was Michael Lewis,” Sean reminds the crowd at the Aria, “who got the ball rolling. And he has a new movie coming out, Moneyball—”

“Oh, don’t plug him,” Leigh Anne interrupts good-naturedly. “He’s made plenty of money off us.” Big laughs from the crowd—she has a point. But so does Sean. Without The Blind Side, the Tuohys would be a family of local saints; with it, they are something like national heroes, touring the country from speaking engagement to speaking engagement on a kind of paid victory lap. They may be the most enterprising beneficiaries of a phenomenon now so common it deserves to be called the Michael Lewis Effect—the way the author makes his subjects into celebrities just by writing about them, endowing obscure figures with major profiles, intellectual prestige, even earning power.

“He changed my life,” Oakland A’s general manager Billy Beane had told me the day before, bouncing through the Oakland Coliseum on a golf cart between his own press appearances for the movie Moneyball, adapted from Lewis’s baseball book turned management manifesto. Beane had been a backroom-style executive in a forgettable market—a pretty good gig if you like baseball, but nothing that would get you recognized in the street—before Lewis’s 2003 Moneyball proclaimed him a genius for his team’s use of sabermetrics, an arcane statistical method of evaluating players. The book, which sold over a million copies, changed the way baseball was played, made “Moneyball” a shorthand term for data-driven innovation in any field, and turned Beane himself into a savant legend well outside of baseball circles. Though he’s still not quite as well known as the guy who sneaks up behind him and slaps him on the back as Beane walks to his next interview. “Hey, man,” says a familiar voice. That would be Brad Pitt, who plays him in the movie.

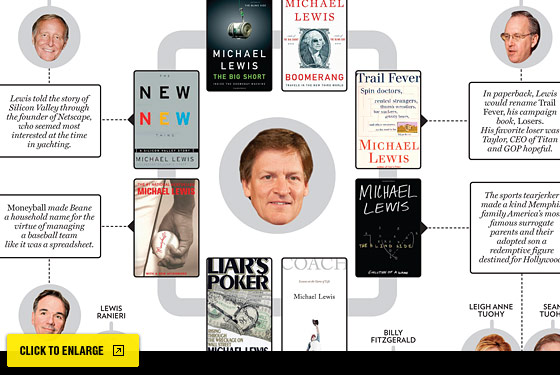

Photographs: Skip Bolen/Getty Images (Lewis); Eric Charbonneau/Getty Images (Beane); John Shearer/Getty Images (Collins Tuohy); Donna Svennevik/ABC via Getty Images (Oher); Jeffrey Mayer/Wireimage/Getty Images (Sean And Leigh Anne Tuohy); Jack Ainsworth/AP Photo (Taylor); Daniel Acker/Bloomberg via Getty Images (Gutfrund); Jamie Rector/Bloomberg via Getty Images (Ranieri); Patrick McMullan (Remaining)

“Michael does this over and over again,” says Don Epstein, the agent who handles Lewis’s speaking engagements, which are plentiful and remunerative. Epstein also handles Lewis’s remarkable spillover: When Lewis does a book, he often puts the people he writes about in touch with Epstein, because, inevitably, they are going to need an agent, too. Even supporting characters are in demand: Epstein books for Paul DePodesta, Moneyball’s number-crunching straight man; Susan “Miss Sue” Mitchell, who tutored Michael Oher in The Blind Side; and Meredith Whitney, the financial analyst whose early warnings about subprime debt were highlighted in Lewis’s financial-crisis narrative The Big Short. “It’s almost like he stamps his own brand on you by writing about you,” says Whitney.

Lewis is often referred to as a business writer, and this is sort of true, in that his narratives usually focus on some kind of market, be it for bonds or baseball players. But he’s a business writer only in the same way that Malcolm Gladwell is a business writer. What most interests him are people and how they behave. He tends to favor stories about mavericks—like the Tuohys, Beane, Whitney, and Steve Eisman, the eccentric short-seller star of The Big Short—smart people who identify gaps of logic and market inefficiencies, and take advantage of them.

He can write about these kinds of people with such skill in part because he is one of them. At a time of peril for his industry, Lewis has managed to build what amounts to a personal empire of long-form journalism, with a Warren Buffett-like collection of brands and eye for the next big thing. “He’s got good instincts for the individual story and for the broader picture of where that story belongs,” says Vanity Fair editor Graydon Carter. “The big story of the day is the world financial crisis, and he’s the most kick-ass business writer out there.”

His aptitude for translating and enlivening financial concepts has made him an indispensable observer of the crisis: In May 2010, Politico reported that The Big Short had been name-checked on the official Senate record at least fifteen times since its publication just two months before, and that Hill staffers had been calling Lewis at home for advice. “I was watching television the other day, and Barney Frank was quoting him like he was a Nobel laureate,” Whitney tells me. This spring, Lewis was invited to Washington to speak to the Democratic Caucus. Afterward, senators came up to him, fanlike, asking for autographs. “I have to believe that’s how a lot of those senators learned about the crisis,” says Whitney.

This week, he’ll publish a follow-up, Boomerang: Travels in the New Third World, a collection of hilarious reported essays he wrote for Vanity Fair that finger Icelandic elves, greedy Greek monks, and a German obsession with shit as a few of the culprits for the European economic collapse. With the continent in an economic meltdown nobody seems to really understand, these witty ethnographic studies have been received like Rosetta stones. It will be no surprise if senators are soon consulting them, too.

Lewis will soon be moving on to other things. The success of Moneyball and The Blind Side means Hollywood is smiling on him: HBO is developing his pilot for a fictionalized series about immigrant baseball players, which was inspired by an article he wrote for Vanity Fair, ABC has optioned his fatherhood book Home Game, and Warner Bros., which has been holding onto the rights for Liar’s Poker for years, has finally hired a director and commissioned Lewis to write the script. He’s also planning on writing a movie based on his book about Billy Fitzgerald, his high-school baseball coach. And there’s a stack of new ideas, including a sequel to Moneyball, in manila folders in his office, waiting to become magazine articles and books and movies and, eventually, other people’s Las Vegas speaking engagements.

“It’s really one of the most remarkable long-form journalism careers,” says Gerald Marzorati, his former editor at The New York Times Magazine. “He’s had at least as big a career as Gay Talese or Joan Didion or Tom Wolfe. ”

If not bigger: What other journalist can claim to have changed the way the game of baseball is played, influenced resolutions like the Dodd-Frank Act, and possibly inspired Sandra Bullock to adopt a black baby?

Then again, not everybody is so impressed. “Everybody thinks he’s like this icon, like he’s just the most brilliant, intelligent person ever created,” says Leigh Anne Tuohy. “We don’t see it. We just think he’s goofy and odd.”

My talking to Michael Lewis’s subjects was actually Michael Lewis’s idea. You can’t write about a master of character studies without wondering how he might do it himself. “I wouldn’t do it,” he said, before being quickly reminded by my expression that most journalists don’t have the luxury of turning down assignments from their employers. “If you forced me to do it,” he continued, “I’d go see the people I wrote about. I’d go see the main characters, the people whose lives I kind of entered. I would go through them. I might not even talk to me,” he said, warming to the idea, which he compares to lost-wax casting: “You don’t write about the person; you write about the person’s effect.”

It was too late for that, of course. I was already sitting across from him at a place called Saul’s, where we’d come for breakfast following a two-hour hike near his home in the Berkeley Hills. But after a few phone calls, it became clear why he might favor that particular approach.

“He’s intoxicating because of his intelligence,” said Billy Beane.

“It’s a pinch-yourself honor to be written about by him,” said Meredith Whitney. “I’ve never met anyone like him. Even in the same sphere as him.”

“I think Michael Lewis is the best satirist writing in English and has been for the last couple of decades,” said Tom Bernard, who has considerably mellowed since Lewis dubbed him the “Human Piranha” and “the grand master of Fuckspeak” in Liar’s Poker, Lewis’s first book. “I think of him as the reincarnation in the United States of Evelyn Waugh.”

If he’s a satirist, he’s one who gets quite close with his subjects. “He basically had a key to our house,” says Leigh Anne Tuohy. “Whenever he came to town, we made him go to church. We said, ‘If you want to talk to us, you’re coming to church.’ ” To their dismay, Lewis, an atheist, resisted conversion. “Lord knows we tried,” says Sean Tuohy. “We had people praying for him.”

Billy Beane has similarly misty memories. “We sort of became a triumvirate, me him and Paul,” he says. “He became sort of a nonpaid colleague.”

When I sit down to write, I like to think everybody is going to love me.

And Lewis keeps in touch. In the summer, he and the Human Piranha go biking in Aspen, and when the Piranha wrote a novel, Wall and Mean, Lewis introduced him to an editor at Norton, which published it. When the Lewis family went to Miami last year, they stayed in an apartment belonging to Jim Clark, the Netscape founder and protagonist of The New New Thing. He still sees Morry Taylor, a.k.a. “the Grizz,” whose quixotic presidential campaign he covered in 1996. “The New Republic has never sold as many magazines as when Lewis was writing about me on the campaign trail,” Taylor says proudly. “And the goofy editor was yelling at Michael, ‘Hey, I sent you out to write about the campaign, why do you keep writing about the Grizz?’ Because the other people are boring, that’s why.”

Lewis recently had dinner with Taylor and his family. Afterward, the Grizz asked to speak to Lewis’s daughter Dixie, alone. Dixie came back grinning, her 4-year-old hand clenched tightly around a present Morry had given her. “It was a hundred-dollar bill,” says Lewis, cracking up. “He told her to spend it on a night on the town!”

Lewis has been criticized for falling too much in love with his subjects. But with people like these, how can he help it? “Michael Lewis is an incurable romantic,” says Taylor. “That’s why he’s been married three times.”

Until not long ago, Lewis was still simmering over an actual “lost wax” profile of him that highlighted precisely that fact, a 1997 Vanity Fair story in which the writer Marjorie Williams quoted mostly his jilted lovers. “If you’d have put me in a room with anybody from that place ten years ago, I would have taken a swing at them,” Lewis says. And today? “That writer’s now dead, so what are you going to do?”

Lewis was 36 back then, as handsome and privileged as a popular guy in a John Hughes movie. He was about to marry his third wife, the MTV correspondent Tabitha Soren, and publish his fourth book, and the Vanity Fair article appealed to peers in the industry who resented his seemingly effortless success. “I once asked him, ‘What is the worst thing that ever happened to you?’ ” one ex told Williams. “And he said, ‘Not getting elected president of the Ivy Club at Princeton.’ ”

Even Lewis will admit that he has led something of a charmed life. He was born looking like something out of a Brooks Brothers catalog, grew up in a well-to-do, generations-old New Orleans family, and has aged in that way that Robert Redford has, in that he looks now basically the same but somehow more solid. “He’s a direct descendant of Lewis and Clark,” says Taylor. “That’s on his dad’s side. On his mother’s side, Thomas Jefferson. Or whoever it was that bought Louisiana from the French. His dad is a lawyer. His grandfather was the first Supreme Court justice of Louisiana. The whole family is very southern, the hospitality, the prim and proper, all of that.”

He managed to get into Princeton despite being a far from stellar student in high school. “He had such bad grades,” says his mother, Diana Monroe Lewis, who is in fact a descendant of James Monroe. “But he always had the verbal skills,” she added. “He could talk his way out of any situation.”

He could talk his way into situations, too. After Princeton, Lewis was studying for a master’s degree at the London School of Economics and playing on their Perrier-sponsored basketball team when a distant cousin invited him to a dinner for Queen Elizabeth. By the end of the meal, he’d managed to charm the woman next to him, the wife of a Salomon Brothers managing director, into asking her husband to find him a job. It was a lucky break: The material he got working as a junior bond salesman at Salomon begat Liar’s Poker, although you do have to wonder what could have been if he’d been seated next to the Queen Mum.

“Despite the delight he takes in lampooning Wall Street,” says Tom Bernard, who worked alongside him, “as a newly minted salesman he did very well.” He put it a bit differently in the book, as the “Human Piranha”: “That is fucking awesome,” he tells Lewis after a big sale. “You are one Big Swinging Dick, and don’t let anyone tell you different.”

But Lewis hated working on Wall Street, he says. Not just the values of the place but the whole “tooth-and-claw atmosphere.” He’d intended Liar’s Poker to be a cautionary tale and was dismayed when it became something of an advertisement. “Overt ambition,” he tells me, “people who are obsessed with success at every turn … I find that off-putting.”

But also, it would seem, alluring. He seems inexorably drawn to what he refers to as the “arena of ambition”: Wall Street, Silicon Valley, Washington, professional sports. Of course, Lewis himself doesn’t suffer from any ambition deficit—no story is too big for him, and he’s always finding a way to maximize the value on the investments of his time. “He is the most opportunistic writer I know, and I mean that in the best possible way,” says Kyle Pope, who edited Lewis at Portfolio.

When he talks about ideas, Lewis can sound like a hedge-fund manager discussing a great trade. “It’s kind of amazing that Moneyball was available to be written at all,” he says, sitting in his office in a bungalow off the back of his house in Berkeley. “Billy Beane’s doing this thing that is totally original, under the noses of the mainstream media,” he said. “That amazed me that opportunity existed.” Part of the reason, he came to realize, was the relationship between sports reporters and their subjects. “It is amazing how much contempt there is for the professional media that surrounds any given enterprise,” he says. “I find it all the time. Silicon Valley entrepreneurs think the tech journalists are all stupid. The sports people think that about the sports journalists. They don’t say that to the sports journalists, because they want the sports journalists to be nice to them. But the level of contempt is very high. You need to kind of cut through that,” he says. “You’ve got to be willing to not be a member of the tribe. Like, you can think what you think about journalists, but don’t put me in that category, because I’m not that.’ ”

The places in his new book, Boomerang, were also blessedly undercovered. “I kept thinking, Why hasn’t the really big piece been done?Why is this available to do? Why is this investment opportunity available to me?”

The reason, of course, is that he is Michael Lewis. Magazines these days aren’t willing to pay just anyone to go to Europe for 10,000-word semi-satirical finance pieces, especially at Lewis’s rate—$10 a word when he left Portfolio for Vanity Fair.

And now that Europe is on the verge of collapse, Lewis couldn’t be happier, like a distressed-market investor. “The timing for Boomerang is unbelievable,” he said. “It’s going to get worse and worse and worse. I’m going to be on Jon Stewart, and Greece is going to be leaving the euro. Sometimes you get lucky in the moment. Boomerang is really going to get lucky in the moment.”

Lucky for him, anyway. The essays in Boomerang haven’t endeared him to European leaders trying to convince the world of their solvency. “Iceland won’t let him go back,” says Sean Tuohy. (Lewis on Iceland: “Icelanders are among the most inbred human beings on Earth.”) “God knows, he goes to Greece he’s going to get shot.” (Lewis on Greece: “A nation of people looking for anyone to blame but themselves.”)

And not everyone whom Lewis writes about finds it a warm, respectful experience. In February, Lewis was sued by a New Jersey–based investor named Wing Chau, who opened The Big Short to find himself playing the greedy fool to Steve Eisman’s righteous genius. By the sound of the complaint, he enjoyed the book, despite being unhappy with his role in it:“Consistent with the engaging narrative of heroes and villains Lewis set out to create, The Big Short purports to recount the thinking and conduct of a few investors like Eisman who foresaw the crash. And it purports to recount the actions and statements of the ‘villain’ CDO managers, particularly Wing Chau, who supposedly brought about the calamity.”

Even some of his boosters agree that Lewis sometimes stretches the facts. “Michael’s a great storyteller,” says his mother. “He’ll take the facts and he will—he never lies, but he tends to exaggerate a little.”

Early on, when Sandra Bullock was starting to hang around Leigh Anne, and singer Tim McGraw started inviting Sean out to ball games, Michael Lewis warned the Tuohys about letting themselves get carried away. “You’ll have the rise,” he told them, but after that inevitably comes the fall. As he knows, a winning streak can only go on so long before the backlash begins.

This summer, it seemed like it might be time for a backlash against Michael Lewis. The advance press for Moneyball reopened debate over the wisdom of sabermetrics. When he postulated, in his essay about Germany’s role in the financial crisis in the September Vanity Fair, that the country’s behavior was driven by national guilt over the Holocaust and an even more deeply rooted Scheisse fetish, you could practically hear the click of the claws snapping out across the Internet. “Lazy,” said Mother Jones. The Times Magazine called it “a lot of hot air.” “Is Michael Lewis’s writing rolling downhill?” asked The Economist headline. “I thought that was the worst piece of his career, personally,” says Taylor. Others called the story little more than an ethnic joke.

Lewis does his best to ignore what he calls “the noise.” “I’m sensitive enough to criticism that if I pay attention to it, it may make me a worse writer,” he says, maneuvering his car through the Berkeley Hills. “When I sit down to write, I like to think everybody’s going to love me,” he adds. “Or at least I don’t think anybody’s going to hate me. It’s pronoia, right, is that the word? Everybody’s out to love me, not everybody’s out to hate me? I think basically that way as I move through the world.”

But occasionally anger descends like red haze, quickly and certainly. “I am quite capable of getting in a fistfight, if the moment is right,” he says. “When I get pissed, I get really pissed. I go to that level of anger.” The paperback edition of Moneyball contains a fifteen-page retort to his critics, whom he refers to as the “Women’s Auxiliary.” But lately, he’s managed to keep his fights inside his head. “I’ll be like, ‘I just wrote a 12,000-word piece about Germany in Vanity Fair. And people are reading it.” He laughs. “You do that. Do that. I’m waiting for it.” He shakes his head. “People whose job it is to generate an instant view … You do that enough, you forget what that person who is creating things did. All you are doing is responding to the things in front of you.” It still can take him about six hours to calm down. “Engaging with it is usually a lot more trouble than it’s worth.”

Except, that is, on the occasions when it could be worth something. On the drive back to my hotel in Berkeley, he remembers that he’d digressed earlier when I’d asked him about the Wing Chau lawsuit, and he thoughtfully brings the conversation back around to it. He’d tried like hell to get Chau’s side of the story when he was reporting The Big Short, but Chau wouldn’t take his calls. The lawyers for his publisher thought that it was just a nuisance suit, he said, but Lewis had been thinking about it and he realized it was actually an opportunity. Nobody has really explored the role of CDO managers who hand-selected crappy securities for places like Merrill Lynch. But now Chau would probably be required to file paperwork explaining what it was he actually did. “There might be a very good piece inside that, actually,” he says, pulling up to the curb. “That someone can do that and generate self-righteousness is interesting. Psychologically interesting. It may not be a complete waste of time. It may just be material.”