The first time they had sex, during that initial exploration of unfamiliar flesh, John Ross uttered words to Ann Maloney that would sound to her like prophecy. “You have the body of a young girl. You need a baby.”

This compliment, though gallant, could not have been objectively true. The first time Maloney and Ross had sex, he was 54 and she was 47. Maloney may have looked good for her age, but she most certainly did not have the body of a young girl. And the subject of babies, not in wide use as a come-on in any cohort, might have struck another woman so deeply middle-aged as creepy. But Maloney had no children at the time, and she wanted them—badly. As she recalls that ancient intimacy over martinis at an Upper East Side restaurant, her voice reverberates with remembered pleasure. Her husband gazes on fondly as she describes the moment when, as she approached 50, her fantasy came true. Maloney had deferred motherhood for the typical reasons: an unhappy first marriage and a late career switch—in her case from interior designer to psychiatrist—that required years of school and training and a radical relocation from suburban Texas to New York City. When she met her future husband, Maloney was establishing her practice and building a national reputation. She was, finally, ready.

Ross had his own procreative urges. Also a shrink, also divorced, he felt that he and his first wife hadn’t raised their son, now 35, “the way I thought he should be raised. I wanted to rear a family in a better way.” As often happens between mature couples who know what they want, things progressed quickly. The two married within eighteen months of their first date. With their medical backgrounds, they were clear-eyed about this biological fact: The odds that a woman over 45 will get pregnant in the usual, no-tech way are dauntingly low. So, skipping agonizing years of “trying,” they began the process of securing a donor egg. With Ross’s sperm, Maloney’s womb, and the gametes of a much younger woman, they would build the family they both craved.

Donor eggs result in live births about 60 percent of the time, no matter how old the mother-to-be is. But clinics set various age cutoffs, and when Maloney and Ross were attempting to conceive, she was 48, which represented the outer limit. Even after NYU raised concerns about her age, Maloney says she never wondered if she was too old to have children.

Eventually, Columbia University took the couple on. A donor was identified, ejaculate dispensed into a sterile cup. Some of the resulting embryos were immediately transferred into Maloney’s uterus, the remainder sent to the deep freeze for future use. Ann Maloney gave birth to Isabella in February 2001, a blissful event followed by severe postpartum depression followed by the hormonal rages that accompany the onset of menopause. A townhouse was purchased, two flourishing practices shuffled and reshuffled to accommodate newly complicated priorities. Lily was born when her mother was 52. This time, Maloney had to be brought out of menopause with hormones before she could get pregnant.

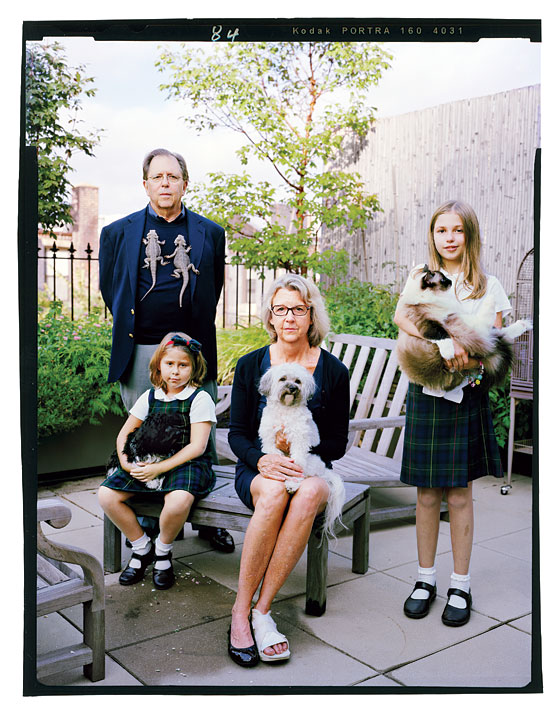

Today, Maloney and Ross, 60 and 66, inhabit their home with a rotating crew of housekeepers, a couple of fish tanks, a cockatiel, two bearded dragons, two dogs, two cats, and a dwarf hamster. Lily and Isabella are 7 and 10 and come with a docket of demands befitting their age—soccer games, birthday parties, sibling fights.

“You don’t know how high-energy, actually, both of us are,” Ross says. “I acted in 32 productions at Harvard, worked with Erik Erikson, graduated near the top of my class. We are both very intense, and also nurturers.”

You know such people. They are your colleagues and friends, your boss or your mother’s cousin. You see them on the subway—as I did recently at the Bloomingdale’s stop. From behind, the woman looked like a Manhattan-mom archetype: a slim-hipped, pony-tailed blonde in jeans struggling with a stroller. As I passed her, I saw that she had the too-tanned and haggard face of a very fit grandma. In parks and playgrounds, you note a grizzled grown-up and his dimpled charge, and you do the math and you wonder.

The age of first motherhood is rising all over the West. In Italy, Germany, and Great Britain, it’s 30. In the U.S., it’s gone up to 25 from 21 since 1970, and in New York State, it’s even higher, at 27. But among the extremely middle-aged, births aren’t just inching up. They are booming. In 2008, the most recent year for which detailed data are available, about 8,000 babies were born to women 45 or older, more than double the number in 1997, according to the Centers for Disease Control. Five hundred and forty-one of these were born to women age 50 or older—a 375 percent increase. In adoption, the story is the same. Nearly a quarter of adopted children in the U.S. have parents more than 45 years older than they are.

The baby-having drive in this set is so strong it’s recessionproof. Since 2008, birthrates among women overall have declined 4 percent, as families put childbearing on hold while they ride out hard times. But among women over 40, birthrates have increased. Among women ages 45 to 49, they’ve risen 17 percent.

Reproductive technology accounts for the sharp rise in the numbers. Women over 45 who want to carry their own babies most often use donor eggs, though egg freezing, a more cutting-edge method, offers early adopters another option, a kind of reproductive DVR for circumventing the inflexible and often inconvenient schedules handed down by Mother Nature. (Save your shows, and watch them when you have time; put your own eggs on ice, and wait for Mr. Right.) Egg freezing now gets write-ups not just in medical journals but also in Vogue, where a long feature on the technology appeared this past May between articles on avant-garde gastronomy and the fashionable art of mismatching patterns.

But just as important as those medical advances is a baby-crazed, youth-crazed culture that encourages 50-year-olds to envision themselves changing diapers when a decade ago they might have been content to calculate the future returns on their 401(k)s. Nothing—not a sports car, not a genius dye job—says “I’m young” like a baby on your hip. “He’s given the house a renewed spirit and purpose,” John Travolta told People magazine earlier this year about his new son, Benjamin. Travolta is 57. His wife, Kelly Preston, is 48.

Born before the Stonewall riots, gay men in their fifties never expected to be invited into the ranks of the conventionally domesticated. But thanks to decades of activism, they too have the option of choosing a very traditional path: first love, then marriage, then that backbreaking baby carriage. They realize “that they can have what they always thought they couldn’t have,” says John Weltman, founder and president of Circle Surrogacy, a Boston agency that matches prospective parents with surrogate mothers. “They’re seeing it happen.”

Last winter, the gossip columns reported that Stefano Tonchi, the 51-year-old editor-in-chief of W, had married David Maupin, his partner of 25 years, and that the couple was expecting twins through a surrogate. The guest list for their East Hampton baby shower was said to include Tory Burch and Martha Stewart. Now that their daughters have arrived, the couple’s acquaintances are wondering how Tonchi (who declined to be interviewed) is coping with the addition of two barfing babies to his fastidiously posh apartment.

Whatever their tastes in home décor, old parents face a version of the judgment implicit here: They have no idea what they’re in for. More than that: This is just not right. A new child may be a blessed event, but when a 50-year-old decides to strap on the Baby Björn, that choice is seen as selfish and overwhelmingly prompts something like a moral gag reflex. One post I saw on a parenting message board put it this way, and seemed to speak for many: “Just because you can,” it read, “doesn’t mean you should.”

Herewith, the results of an unscientific poll.

Should people have babies at 50? I asked my mother (who had her third and last child two days after her 32nd birthday). “No,” she answered instantly.

“Jesus,” responded a colleague—male, straight, early forties, and the father of three young kids. “Wasn’t it hard enough at 30?”

“I think it’s bizarre,” said a friend who is gay and pushing 50 of his peers on the baby-shower circuit. “Jimmy has two grandpas? It seems like more than a midlife crisis.”

I posted a variation of the question on UrbanBaby, the go-to online chat board for parenting snark. “Freakish” was one commenter’s assessment of people who have children late in life. “Unfortunate for them and the DC (Dear Child)” was another.

Concern for the misbegotten children tops the list of objections. Obstetricians, who have to deal with the fallout of these procreative impulses, are especially harsh (in private, for these people are their patients). “I see them in the hospital, all stroked out,” the result of pregnancy-induced hypertension, an OB once told me. These are cases in which baby lust seems to obliterate any sane calculus of the real dangers involved: After 35, the risk of preterm labor increases by 20 percent, and preemies can have lung problems, digestive problems, brain bleeds, and neurological complications, including developmental delays and learning issues, depending largely on their gestational age at birth. After 40, a pregnant woman is likelier to become afflicted with preeclampsia, gestational diabetes, and hypertension—the worst outcomes of which can result in the death of the fetus and occasionally the mother as well. It is also after 40 that the risk of having a child with autism increases—by 30 percent for mothers and 50 percent for fathers, says Lisa Croen, a senior scientist at Kaiser Permanente. Advanced paternal age is likewise associated with miscarriage, childhood cancer, autoimmune disease, and schizophrenia and other neuropsychiatric disorders. “Everyone wants to believe it’s not going to happen to me,” says Isabel Blumberg, an OB/GYN at Mount Sinai. (Ironically, the risk of Down syndrome among over-45 parents is low: Donor eggs are young eggs, and don’t make the mistake during cell division that leads to that condition.)

What really bugs the acquaintances of these oldest parents is their denial about their decrepitude. Everyone with kids knows that parenthood is the never-ending revelation that you can always be more exhausted. It’s squatting and standing and bending and lifting and standing up again. It’s handling poo and being smeared with goo and never, ever, ever, sleeping. How can the oldest parents possibly hack it? Babyhood is hard enough, but as they grow, children need to run around in the fresh air, ride bikes, and throw balls. How can an aged dad keep up when his physical strength is known to diminish 15 percent each decade after his 50th birthday? When he’s got even odds of eventually getting heart disease? How can a 65-year-old mother summon the stamina and mental toughness to enforce a curfew? “Children are entitled to at least one healthy, vibrant parent,” says Julianne Zweifel, a psychologist who treats fertility patients in Wisconsin. “Just because you’re alive doesn’t mean you’re healthy and vibrant.”

“Mommy, he’s not sharing.”

It’s a beautiful day at the town pool near Sea Cliff, Long Island, with summer colors as bright as a Disney movie. Kate Garros stands in the shallow end, as her daughter, Alexandra, age 7 and slick as a seal, swims up to tattle on her twin brother, John. Kate has blonde hair and a wide, friendly face; her polka-dot blue suit covers her without flattery or fanfare. The twins are hers, conceived through donor eggs with her second husband when she was 53, but chronologically she is the peer of the grandparents seated in a row on the pool deck, lavishly slathered with sunscreen. Garros paid the senior-citizen rate at the pool’s entrance.

Ally and John climb on Kate as she talks, wrapping themselves around her body and pushing into her flesh before wriggling away in different directions. We chat about schools, sports, and summer vacation as the children approach and retreat, showing off new strokes and somersaults. Ally persuades her mom to make a bridge with her arms under which she can swim. The first time goes fine, but as she leaps onto the pool deck to do it again, she accidentally steps on her mother’s finger. “Ow! That really hurts!” Kate holds up her hand and steps away from the pool’s edge. She has arthritis, and her daughter has hit a hot spot. Later, heading for the parking lot, John asks his mother a question that measures the miles between them. “Mom,” he says, “do you like Cee Lo Green?”

According to the life-expectancy charts issued by the CDC, a child born to two 50-year-old parents will lose her father when she’s 25 and her mother when she’s 30. She will grow up, says Monica Morris, with an awareness that her parents are older than other parents, and she will worry, more than her peers, about their inevitable mortality. Morris is a sociologist, and for her book Last Chance Children, she interviewed 22 adult kids of older parents. One recalled that as a girl, she would enact a nocturnal parental ritual in reverse: She, the child, would creep out from her bed to listen at her mother’s door for the precious sound of breathing. “She was just terrified,” Morris says, “that her mother would die.” That same kind of child may grow up to discover that just when she needs to prepare for grad-school exams, put in long nights at the office, or tend to small children of her own, her parents have grown frail and in need of care. Her own children may never have grandparents.

Nancy London finds that she’s in the awkward position of having to reverse herself. As a co-author of Our Bodies, Ourselves, published in 1973 (the year the U.S. Supreme Court upheld Roe v. Wade), London was among those who argued—convincingly—that biology was not destiny, that women should take control of their lives through birth control and find pleasure and independence in sex. Her 2001 book Hot Flashes, Warm Bottles attempts to provide empathic guidance to women who find themselves, as she did when she had her daughter at 44, having to deal with small children, elderly parents, and their own menopausal mood swings all at once.

But for London, 50 is too far. She now believes that biology is destiny and that a woman who delays childbearing for decades because she has other priorities isn’t living in reality. In the seventies, the Second Wave feminists wanted to “have a career, travel, have sexual adventures, whatever we thought freedom meant,” London recalls. “But then we had to find out that biology is not some patriarchal concept created to keep us barefoot and pregnant. To mother is part of our nature. To toss that out the window and say, ‘Hey, that’s not for me,’ and then at 50 to say, ‘Oops, forgot to have a baby’—something is not processed in our thinking.”

London has a suggestion. The human body has an organic deadline—menopause, which occurs around age 50—after which baby-making is no longer possible. Why not respect it? In our fifties, we take stock, get reflective, move into another phase not so defined by drama and personal drive. We do not, traditionally, mop mashed potatoes off the floor. Choosing to have children at 50 disrupts life’s natural trajectory, causing needless suffering and disharmony for both parent and child. “It’s irresponsible,” London says.

And if you meet the love of your life at 50 and the desire to start a family sets in? You can try to adopt. Or “maybe what you do together,” she says, “is grieve for your loss and find another way to serve the planet.”

I should note at this point that I realize how lucky I am. I had my first and only baby when I was 40 years old, and joyously brought her home to the brownstone-Brooklyn neighborhood where we live. Thanks purely to the fluke of my inhabiting that particular moment and our particular place of residence, my age has been an unremarkable fact of our lives. No one has doubted my mothering abilities or questioned my motivations because I had my child later than most people; lots of the moms in my daughter’s class are around my age. But it’s only because I happened to fall on the acceptable side of the line that I was spared the bigotry directed at parents who dare to cross it. Had I waited a little longer to get pregnant, or lived in an earlier era, I would have been one of the freaks.

Here is why the arguments against old parents put forth by this article thus far are actually all bunk: They rest on the assertion that people above a certain externally imposed cutoff should not have children because it is not natural—and nature is a historically terrible arbiter of personal choice. American states used to legislate against interracial couples on the basis that miscegenation was “unnatural.” Some conservatives continue to fight gay marriage and gay parenthood on the grounds that homosexuality is “unnatural.” Broad-minded people see these critiques for what they are: bias and personal distaste hiding behind an idea of natural law. And yet some of these same broad-minded people still feel comfortable using chronological age to sort the suitable potential parents from the unsuitable. That’s because those judgments, and the backlash they’re fueling, are a product of ageism, the last form of prejudice acceptable in the liberal sphere. Sitting so ostentatiously on the boundary between “youth” and “age,” 50-year-olds threaten an image we hold of good parents (i.e., the handsome, glossy-haired ones depicted in the house-paint ads). By acting young when they’re supposed to be old, they cause discomfort for the people around them. Parents like Kate Garros have felt this all too acutely. “If you don’t meet people’s expectations of what a mother looks like, they can’t hack it,” she told me.

The reason people couch their objections to older parents in concern for the children is to mask their more impolitic uneasiness about the parents themselves. But those objections are hypocritical: The number of grandparents in America who have primary responsibility for children rose 8 percent to 2.6 million people between 2000 and 2008, according to the Pew Research Center. But they are not deemed unfit caregivers simply on the basis of their age—on their ability to throw a ball or stay up late. What’s more, the available science says that for all the disdain directed at older mothers and fathers, their kids are likely to fare just fine. There are, to be sure, myriad ways to inflict grief and suffering on children (including and especially by having them too young), and the heightened dangers of a middle-aged pregnancy demand private risk calculations. But being an old parent, in and of itself, does no harm.

When a 50-year-old decides to strap on the Baby Björn, the choice prompts something like a moral gag reflex.

In 2008, Brad Van Voorhis, head of the fertility clinic at the University of Iowa, decided he wanted to measure how well children conceived through in vitro fertilization do on intelligence tests, hoping to dispel lingering concerns about their cognitive abilities. So he and his team compared the standardized-test scores of 463 IVF kids ages 8 to 17 against the scores of other kids in their classes. They found that the IVF kids scored better overall and in every category of test—reading, math, and language skills. And they found that the older the mother, the better the kid performed.

Van Voorhis guesses that the children of older mothers outperform their peers because the mothers, who’ve waited so long to have them, are more engaged. It’s a recipe for success: “Fewer kids at home, more attention to the kids they do have, and more money to devote to their education.” Other studies corroborate these findings. In research published in the journal Fertility and Sterility in 2007, Richard Paulson, head of the fertility program at the University of Southern California, found that mothers in their fifties reported less parental stress than those in their thirties and forties, the same level of mental functioning, and the same perception of fatigue. The fiftysomething women in his small national sample, incidentally, were also less likely than their counterparts to employ a nanny. They are more checked in.

Some evidence even suggests that having babies late extends a person’s life. Boston University’s Thomas Perls has been studying centenarians since 1995. He found that women who gave birth to children after the age of 40 were four times more likely to live to 100 than those who did not. His study has nothing to do with reproductive technology or adoption: It shows a connection between an unusually healthy reproductive system and longevity. But longevity is complex, and Perls hypothesizes that there’s something about living with kids—all that running around, all that responsibility, all that social connectivity in the shape of picnics and playdates—that maintains health. People who’ve made a big investment to have little kids take care of themselves, and people who take care of themselves live longer.

In Perls’s view, menopause, the definitive end of a woman’s natural fertility, can be regarded as an evolutionary relic. Ten thousand years ago, when humans died at 50 and childbirth at any age was perilous, menopause had what evolutionary scientists call “a survival benefit”; it protected the species by allowing women, in their final years, to devote themselves to their existing children and grandchildren without assuming the potentially fatal risk of pregnancy. But now the average woman lives to be 81. At 50, she’s nowhere near dead.

At no other time in human history have people expected to reach their 50th or even 60th birthday and have one of their parents at the party. We have come to sentimentalize the wedding portrait with three or four generations, but it’s that sense of entitlement that’s out of whack. A dramatically lengthened life expectancy (21 years in the U.S. since 1960) is a luxury, given to us in the developed West by modern medicine. To lose a parent at 30 is not, by any historical measure, a tragedy.

And even when a parent does die before a child reaches adulthood, that child can thrive. In a 2009 study published in the journal Developmental Psychology, researchers at Arizona State University asked 91 college students to wear monitors that tracked changes in their blood pressure, and to note whether those changes had been preceded by everyday stressors—a fight with a friend, say, or a traffic jam. Half the subjects had lost one parent before age 17. Half were from intact, two-parent homes. The psychologists found that the bereaved students who felt emotionally connected to their surviving parent coped better with life’s hassles, while those who felt neglected by their surviving parent freaked out at the slightest problem. But the most surprising data came from students whose parents were both alive and fell into a category the researchers labeled as “highly protective.” These subjects boiled over at minor setbacks almost as much as the bereaved and neglected group. Another aphorism to add to your parenting-tips collection: Helicopter parents may do more damage than ancient ones. “Evidence from both animal and human studies,” the researchers wrote, “supports the notion that moderate levels of stress in childhood are associated with better handling of stress in adulthood.”

Here’s the final point, and the trickiest. People—straight or gay; married, partnered, or single—who have babies at 50 are often wealthy. The average egg-donor cycle costs $25,000, but the cost can run as high as $35,000 for the eggs of an elite, Ivy-educated girl. A surrogate costs as much as $110,000, which insurance often does not cover. Adoption, depending on how you do it, costs between $20,000 and $40,000 out of pocket.

The resources of affluent older parents provide their children with small but significant benefits. Compared with their 30-year-old peers, 50-year-old women have “access to their own money and clout in the world,” says Elizabeth Gregory, a women’s-studies professor at the University of Houston and author of Ready: Why Women Are Embracing the New Later Motherhood. Thus established, they can chaperone the field trip without job anxiety; financially secure, they can take an extended parental leave when the baby comes.

When I spoke to the literary agent Molly Friedrich by phone, she had just returned from playing “really, really bad tennis” with her two adopted children (9 and 14, from Guatemala and Vietnam, respectively) on a local court covered with “seismic cracks and holes—exhausting and ludicrous.” She is 59 years old and adopted these two kids after her two biological children were grown, because she “couldn’t think of a good reason why not. Every decision I’ve made has been pretty impulsive, not to say reckless. We have a lot of love, we have the space, and we can carve out the time.” In this line of thinking, kids are not a crimp on a lifestyle but brought into a family to share its advantages. “My feeling is—this is going to sound insanely narcissistic—twenty years with my husband and me versus twenty years in an orphanage, there’s no comparison,” says Friedrich. “They have a much better chance flourishing with us than in the places they were born.”

The relative wealth of older parents blunts their supposed shortcomings in other ways. Research supports intuition: Rich people live longer than others. Demographers at the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services have found that the gap in life expectancy between richest and poorest Americans has widened since 1980 to four and half years from three. Rich people are likelier to have good health insurance, and insured people live longer because they can avail themselves of checkups and screening tests. Rich people are likelier not to be smokers, they’re likelier to be thin, and they’re likelier to have good cardiovascular health. (They may be able to play some catch after all.) These data point to loathsome injustices far beyond the scope of this article. But where the welfare of children is concerned, the good health that comes with wealth counts as a check in the plus column.

“There’s 50 and there’s 50,” the fertility doctors like to say, meaning there’s the overweight smoker with diabetes and there’s actress Beverly D’Angelo, who had twins as she was pushing the half-century mark. Paulson’s clinic at USC is known for helping postmenopausal women conceive. Before he’ll treat them, though, he puts them through a battery of tests. A session on the treadmill measures whether a woman’s vessels can expand to accommodate the massive increase in blood volume that comes with pregnancy. An EKG measures the health of her heart, and a psychologist probes her motivations and support system. Paulson will also create in a prospective mother an artificial menstrual cycle to see if her uterus can sustain a pregnancy. Once she clears these hurdles, she’s good to go. “They’re very young 50-year-olds,” he says. “They really are.”

They have to be. Because even for parents in perfect health, 50 is still not ideal, and doctors who earn excellent livings impregnating old women warn against the false sense of security created by the success stories. If you’re willing to carry a child who is not genetically your own, fertility treatment is an emotional roller coaster with mediocre success rates at best. (At 50, prospective parents seeking to adopt a healthy infant face even longer odds.) The University of Texas sociologist John Mirowsky has shown that the perfect age for a woman to have a baby is 30.5. By that point, she has finished her education and found an appropriate partner. She has the maturity to be a good parent, with enough years ahead of her to have more than one child without bumping up against the limits of her fertility.

“I didn’t have any grandchildren. So I decided to make my own.”

But a certain kind of woman—an ambitious woman—is just getting started at that age. And a baby will cost her. There is a direct, positive correlation between delaying childbirth and income level. According to an analysis of census data by Elizabeth Gregory, women with professional degrees who had their first child at 20 earned $50,000 less per year than those who had their first child at 35. A 2003 study of the most senior executives in ten major U.S. companies by the Families and Work Institute found that 35 percent of female executives delayed having children, compared with 12 percent of men. It also found, not incidentally, that three quarters of executive women are married to men who work full time, while three quarters of executive men are married to women who aren’t in the workforce at all. A woman who has to compete with men at work (late nights, weekend conference calls) when those men have wives at home caring for kids is exactly the kind of woman who might find herself in a fertility clinic at 48.

Cruelly, ambition in women is still conflated with selfishness, and the woman who devotes her first decades of adulthood to her career is expected to then waive her maternal impulses. (“You didn’t eat your ice cream when it was on the table. Now you don’t get any ice cream.”) Even gay men don’t face the same judgments as women who decide to become parents late in life, inoculated as they are by the current celebratory mood surrounding gay domesticity as well as history’s long wink at the frisky fertility of men. It’s one kind of punch line when Tony Randall fathers a child at 77, and another, far less kind one when Annie Leibovitz has twins through a surrogate at 56. On the parenting blogs, the cartoon persists, as hateful as the campaign against Murphy Brown: The self-centered female, drinking wine and buying Jimmy Choos for decades, who one day awakens—alone, wrapped in high-thread-count sheets—and remembers the baby she never had. She goes to her doctor and sobs. If she succeeds in achieving her heart’s desire, she’ll just hire a nanny and go right back to work and, in one blog post I saw, refuse to sit on the floor and play with blocks.

Sure, some women are materialistic bitches. But most delay children because they want the independence that comes with work as well as the nontrivial benefits of professional success: a good salary, health insurance, and a stable place in the world. The economic trend lines indicate that the ranks of these women will increase going forward, their decision to put work before childbearing for some period of time not “a lifestyle choice” but a necessity. Men remain disproportionately out of work, leaving the mortgage payments, on top of the child care, to the women in their lives. In 2010, nearly a quarter of wives earned more than their husbands, up from 4 percent in 1970. Women will wait to have children because the conflicting demands they face—have babies! Earn money!—are squeezing them like never before. “We are under unreasonable pressure,” says Angel La Liberte, who runs a California-based website for older mothers. “We are expected to manage a household. We are expected to provide an income, and we’re supposed to have children within a certain age limit.”

It is nearly impossible to have a baby at 50 by accident. “Oops” does not happen; that momentary abandonment of good sense or caution will almost never result in a pregnancy. No matter how a child is procured, whether through technology or adoption, her 50-year-old parents have likely gone through some kind of hell—paperwork, blood tests, questionnaires, waiting, visa applications, mood swings, marital discord, and recalibration of expectations—to have her. These are the most wanted of children. And their parents, some would argue, can give them something that the youngest and prettiest don’t have: the wisdom of age and an abiding sense that life is a precious gift not to be wasted.

Fiona Palin started trying to conceive ten years ago, when she was 38. She underwent six failed IVF cycles and three miscarriages—including, the final time, a miscarriage of triplets. Depressed for years, she decided to give up hope, go back to school, and become a tourism consultant. She investigated adoption. She was keeping herself busy.

Last August, when she and her husband, Nick, who is 63, decided to thaw and use their last remaining embryo, abiding in a freezer since 2002, they were done “with everything but the crying,” she says. “I thought, This won’t work. Don’t put any hopes on it.” It did, though. Fiona learned she was pregnant in the bathroom of a Ralphs supermarket in Los Angeles, where, in anticipation of a long, boozy evening with relatives, she took a do-it-yourself urine test, just to be safe. “I screamed. I was crying hysterically in the toilet. If anyone would have heard, I’m sure they would have called security. I got myself together and went outside, and Nick was there. He said, ‘What’s wrong? What’s wrong?’ and I told him, and then he started crying. So we’re crying in this parking lot of this supermarket.” According to her obstetrician, Fiona’s pregnancy was “flawless.”

On the morning I met Katherine Anna Palin, she was 1 month old. Asleep, scrunched against her father’s chest, she was downy, dewy, seemingly boneless, a miracle of the most ordinary kind. Her parents were brimming over on that sunny day, in their rental near Lincoln Center, with the baby books stacked against the walls and the breast pump lying on the kitchen counter. “I didn’t have grandchildren, so I decided to make my own,” said Nick, shaking my hand and wiping the puke off his polo shirt in a single motion.

Kiki, as she’s called, will never share toys with (or steal toys from) a sibling. She has no living grandparents. Her parents are not blind to these realities, and her mother, born and raised in Australia, already imagines the Australian girls’ boarding school to which she will send Kiki when she is a teenager—an effort in the absence of extended family to give her “sisters.”

“If you look at it from an actuarial standpoint, I might not be around when she’s 30,” Fiona says. “If you sit down and look at the cold, hard facts, this is the truth.” But Fiona shrugs it off. She and Nick are “no regrets” people, a couple who vowed to climb the Great Wall of China while they were still healthy enough to do so, and then did.

“I’m very hormonal still, at the moment,” Fiona says. “And every now and then I just burst out crying. I am so happy. I can’t believe it. I’m just so blessed. And I just wish this on everyone I know.”