A little after 11 p.m. CST on November 6, I was huddled in the bowels of the monstrosity that is McCormick Place, the sprawling convention center in which Barack Obama held his Election Night party in Chicago, gamely trying to sober up after one too many tumblers of Buffalo Trace, when a text message hit my phone that spoke volumes about the victory that the TV networks had just declared for the president over Mitt Romney: “Reality wins,” it said.

There were several ways to read this message. The most obvious was in reference to the reality that the plethora of public polls that so many conservatives had decried for months as deliberately skewed had been proved correct. Another was more partisan: that Obama’s reelection was a triumph of facts and reason over the humbug and make-believe-ism that Romney had been peddling. Given that the text in question came from a poll-obsessed borderline pinko (and, even worse, a Brit), both these interpretations were perfectly plausible. But it was a third sense in which the verdict rang true that struck me as most meaningful: The reality that prevailed last Tuesday was that of the emerging new American electorate.

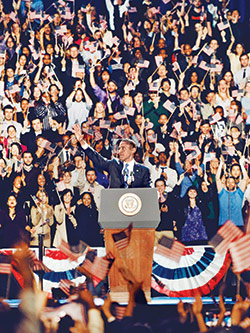

Just as he was in 2008, Obama in 2012 was the proximate beneficiary of that nascent transformation. Taking the stage a bit past midnight with his wife, Michelle, and their girls, the president wore a look of infinite satisfaction, justifiable pride, and even a hint of humility, and then proceeded to deliver his best speech of the campaign: mature and generous, passionate and unifying, shot through with poetry that carried echoes of his past—of 2008 (eight invocations of hope, three more of hopefulness), of his roof-raising 2004 convention keynote (“We remain more than a collection of red states and blue states; we are, and forever will be, the United States of America”)—and prose that promised a revival of the post-partisan approach to the challenges the country faces that made him so appealing to so many in the first place.

Those challenges are enormous, and in some cases require immediate action: to wit, the looming fiscal cliff. For Obama, addressing them carries no small degree of risk, but also offers him the opportunity to build on the achievements of his first term and join the ranks of our most successful presidents. For his Republican counterparts, however, the situation is more urgent—and more dire. Having failed to dislodge an incumbent whom much of the party regarded as both eminently beatable and basically illegitimate, and having lost seats in both chambers and seen cultural liberalism (with the legalization of same-sex marriage in three states and the legalization of cheeba in two) on the march, the GOP finds itself facing something akin to an existential crisis.

The full sweep and scale of these implications weren’t remotely clear to the thousands packed into McCormick Place. All they knew was that, against all forecasts to the contrary, the hour hadn’t run late, nails hadn’t been bitten, the finish hadn’t been photo; Election Night had instead been a vintage No Drama Obama affair. But when it came to explaining what happened, the crowd itself provided a clue, for here you had Obama Nation in all its Technicolor glory: black and white, yellow and brown, every hue but gray—a tableau at stark variance with what you saw at any Romney rally, where the throngs were as blindingly alabaster as Joe Biden’s choppers.

That the essence of Team Obama’s reelection strategy was to capitalize on his strength with what National Journal’s Ronald Brownstein calls “the coalition of the ascendant” had long been clear. Back in May, I wrote a cover story for this magazine laying out Chicago’s plan to focus laserlike on four key voting blocs: African-Americans, Hispanics, college-educated white women, and voters aged 18 to 29. At bottom, the Obaman theory of the case was that, despite the fragility of the recovery and the doubts many voters had about POTUS’s capacity to put America on the path to prosperity, the deft exploitation of coalition politics, together with the ruthless disqualification of Romney as a credible occupant of the Oval Office, could secure the president a second term. That in 2012, in other words, demographics would trump economics.

And so it did, as a glance at the exit polls confirms. Contrary to the assumptions of the Romney campaign, the electorate that turned out last Tuesday was more diverse than 2008’s, not less. Nationally, the white vote fell from 75 to 72 percent, while the share made up by blacks rose from 12.2 to 13 percent, by Hispanics from 8.4 to 10, by Asians from 2.5 to 3, by women from 53 to 54, and by 18-to-29-year-olds from 18 to 19 percent. Obama’s claim on each of those groups was overwhelming: 93 percent of African-Americans, 71 percent of Latinos, 73 percent of Asians, 55 percent of the ladies, and 60 percent of the kids. And that all made the difference in the battleground states. Had it not been for Obama’s vast advantages with Hispanics, he would not have carried Colorado, Florida, or Nevada, and the same was true when it came to African-Americans in Virginia and Ohio. And had it not been for his margins with young voters and college-educated women, the races in Iowa, Wisconsin, and New Hampshire would have been razor-close rather than five-to-seven-point strolls in the park.

Now, make no mistake, Obama’s victory was by no means a landslide, a term impossible to apply to a contest in which an incumbent garners a lower percentage of the popular vote, a smaller number of raw votes, and fewer electoral votes than he snagged the first time around. But equally unmistakable was that Obama’s win was comprehensive and decisive. And taken together with the broad repudiation of Republicans, it endows the president with political capital to spend and more legislative leverage than he has had since 2009.

How Obama will now try to work his will is the subject of wide cross-party conjecture. On the right, it has always been an article of faith that, freed from the constraints imposed by the need to seek reelection, Obama would suddenly and wantonly lurch to the left, governing as the socialist/communist/fascist/anarcho-syndicalist/Black Panther he most surely is deep down in his heart of hearts. But this assessment is more than merely baseless and downright dopey. For all the effects of last Tuesday, the central fact of divided government remains unchanged. Which means that governance from the center—“building consensus and making the difficult compromises,” as Obama put it in his speech—will be required for anything to get done for at least the next two years.

And getting shit done—and not just any shit, but big shit, significant shit, the kind of shit that scholars will scrutinize with care and ideally marvel at—is what Obama has always been about. This is a president unusually focused in the present on what his legacy will be in the future. With Obama’s reelection, one foundational element of that legacy has been secured: the Affordable Care Act, which, had he been defeated, would not only likely have been repealed but retrospectively reduced to one of the causes of his loss. Now, with a second term ahead of him, among Obama’s paramount goals, say his advisers, is to add another glittering trophy to his mantle: at least one more domestic-policy reform tantamount in importance to near-universal health care.

The shiniest such prize would be the achievement of a grand bargain on entitlements and tax reform: a bipartisan agreement that would put the nation’s fiscal house in order for years, and maybe decades, to come. The extent to which Obama pines for this was illustrated by his ardent pursuit of such a megadeal in 2011, which ultimately fell apart when House Speaker John Boehner proved unable to move the tea-party faction in his caucus to accept new revenues.

But now, with the potentially disastrous consequences of the so-called fiscal cliff looming large and with the Republicans’ collective bell having been deafeningly rung by the voters on Election Day, the prevailing circumstances are considerably riper for (grand) bargaining than they were back then. That Boehner, to begin with, is ready to deal was screamingly apparent from the conciliatory tone and softened substantive posture he adopted late last week. And while the Senate minority leader, Mitch McConnell, driven by his own fear of being primaried from the right in 2014, assumed a more typically recalcitrant stance, the presence of sane conservatives such as Lamar Alexander, Bob Corker, Mark Kirk, and Rob Portman will likely be sufficient to counteract the hard-right elements in the upper chamber and make legislating possible.*

Taxes remain a tricky issue with Republicans, to be sure. Having campaigned relentlessly on raising rates for the wealthy, Obama continues to insist that any deal do that. And though Boehner says he’s open to new revenues, he remains opposed to hiking rates. In truth, the speaker may be engaging in Kabuki here. If nothing is done, all of the Bush tax cuts would expire on January 1—which would almost certainly be followed by a restoration of the cuts for earners making less than $250,000. This would be Nirvana for Republicans: spared voting for a tax increase and then allowed to vote, in effect, for a new tax cut. Democrats, meanwhile, would get exactly what they wanted in the first place. A nifty solution all around, no question.

To bring home a grand bargain, Democrats will have to compromise, too. But among the party’s congressional leaders, “the fact that there is going to have to be entitlement reform has been internalized,” says one of the savviest Democratic lobbyists in the capital. And while there will no doubt be some resistance on the left, this person adds, “Obama doesn’t give a damn about those people—he will happily throw them under the bus. That’s what reelection really means for him: He no longer has to worry about his base, about labor, about his left flank.”

For Obama, the political appeal of striking a grand bargain is easy to see, for it would make an ideal bookend to health-care reform—the latter a long-held liberal dream, the former a centrist fantasy so delicious it might bring Pete Peterson to climax. But it is also essential to the country’s economic health, and not just in terms of taming our deficit, but in freeing up resources for the kinds of investment in human capital and infrastructure that are critical to America’s global competitiveness and domestic prosperity (and that should be priorities for any sane progressive, unless they believe that a government that boils down to nothing but a wealth-transfer system from the young to the old is somehow desirable).

Because of the impending fiscal cliff, we will know very shortly whether a grand bargain is in the cards. Either way, the question is, what happens then? And the answer is in plain sight: immigration reform. Indeed, Senate Democrats are already talking about moving on legislation shortly after Obama’s inaugural. During the campaign, the president described the lack of action on this front as one of his biggest first-term failures and pledged to take up the cause “in the first year of my second term.” But the action of consequence here is taking place on the other side of the aisle, where, in the space of 24 hours late last week, comprehensive immigration reform was endorsed loudly by Boehner, Rupert Murdoch, and Sean Hannity (who, like Obama on the topic of gay marriage, proclaimed he had “evolved” on the issue).

It would be difficult to envision, without the aid of psilocybin, a more vivid sign of the GOP’s dawning recognition of the peril it is now facing. With Democrats having gained a potent hold on the coalition of the ascendant, Republicans find themselves in a situation like the one their rivals met in the wake of the 1988 election: markedly out of step with the country, shackled to a retrograde base, in the grip of an array of fads and factions, wedded to an archaic issues agenda. As Matthew Dowd, George W. Bush’s chief strategist in 2004, put it on Good Morning America, the GOP has become “a Mad Men party in a Modern Family America.”

And so, like the Democrats in 1988, the task before the Republicans now is to undertake a root-and-branch redefinition of their party—and not just as a matter of image or “branding,” but on substance and policy. The Daily Caller’s Matt Lewis argued last week that what Republicans need is “modernization, not moderation,” and while I might object that they actually need some of both, an important point lies here. The project the GOP must embark on need not and should not entail a wholesale abandonment of conservative principle. But there is nothing necessarily conservative about ultra-restrictionist positions on immigration, as Bush 43 (who won north of 40 percent of Latinos in 2004, compared with Romney’s 26 this year) would tell you. There is no necessary incompatibility between being pro-life and pro-contraceptive; to the contrary. There is nothing conservative about denying the science of climate change; better to admit the problem is real and advocate market-oriented solutions rather than government-imposed regulations.

Pulling off the Republican modernization project will require institutional resolve and policy innovation, but also something else: individual leadership of the kind that Bill Clinton brought to the Democratic Party a little more than twenty years ago. Who will be the Republican Clinton, the champion of the GOP’s Third Way? Chris Christie? Jeb Bush? Marco Rubio? Bobby Jindal? It’s too early to say, but the maneuverings of these men and others will be fascinating to behold in the days and months ahead.

The stakes for both sides as we forge ahead are immense. For Republicans, a failure to adapt the new demographic realities would risk not just irrelevance but extinction; as Lewis puts it, “a modern political party cannot exist if it concedes the young, the urban, and the educated.” For Obama, the challenge that awaits is to become something more than a transformational historical figure—a great president. It would be easy to predict that, as each side pursues its ends in competition with the other, both projects will end in tears. But what if these projects prove to be as much complementary as competitive? What if each side, for reasons of its own, edges toward the middle and they wind up meeting there to get some business done? I know it sounds crazy. But crazier than Obama winning every battleground state but one? I think not. So bring on the black swans, baby.

*This article has been corrected to show that Mitch McConnell is the Senate minority leader, not the majority leader.