“To talk of diseases is a sort of Arabian Nights entertainment,” ran the epigraph to The Man Who Mistook His Wife for a Hat, Oliver Sacks’s fourth book and his first best seller—the one that made him famous, in 1985, as a Scheherazade of brain disorder. A sensitive bedside-manner neurologist, he had previously written three books, none of which had attracted much notice at all. The Man Who Mistook would mark the beginning of another career, and a much more public one, as perhaps the unlikeliest ambassador for brain science—a melancholic, savantlike physician disinterested in grand theories and transfixed by those neurological curiosities they failed to explain. Sacks was 52 years old and cripplingly withdrawn, a British alien living a lonely aquatic life on City Island, and for about ten years had been dealing with something like what he’d later call “the Lewis Thomas crisis,” after the physician and biologist who decided, in his fifties, to devote himself to writing essays and poetry.

“In those days, he was a complete recluse. I mean, there was nobody,” recalls Lawrence Weschler, a friend and essayist who once planned to write a biography of Sacks. “He was in a kind of rictus of shyness.” Sacks was struggling with writer’s block, wrestling with accusations of confabulation as well as the public’s general indifference to his first books, and would spend hours every day swimming in Long Island Sound, near the Throgs Neck Bridge, miles each way and often at night. “I feel I belong in the water—I feel we all belong in the water,” he’s said, and later echoed: “I cease to be a sort of obsessed intellect and a shaky body, and I just become a porpoise.”

W. H. Auden had become a friend, too, after he’d reviewed Sacks’s first book, the Victorian-ish survey Migraine, in 1971. Auden had also admired his second book, Awakenings, which detailed the miraculous recovery, then tragic relapse, of the near-catatonic patients given the experimental drug L-dopa. The book sold only modestly when published and attracted, he says, no medical reviews. Auden thought Sacks was capable of more. “You’re going to have to go beyond the clinical,” he told him. “Be metaphorical, be mythical, be whatever you need.”

The uncanny case studies of The Man Who Mistook were the mythic course that Sacks has followed ever since (his new book, Hallucinations, is another mesmerizing casebook of neurological marvles). Histories of such unfamiliar or forgotten disorders, tales of damage told in such picaresque and nondiagnostic ways, the stories of The Man Who Mistook struck early readers as landing oddly between science and fairy tale. (A man so unable to distinguish between objects he tried to lift his wife onto his head; a 49-year-old whose memory stalled at 19; a patient who thought Sacks was a delicatessen customer one minute and looked like Sigmund Freud the next.) “They come together at the intersection of fact and fable,” Sacks wrote in its grand preface. “But what facts! What fables! To what shall we compare them? We may not have any existing models, metaphors, or myths. Has the time perhaps come for new symbols, new myths?”

Sacks lives and works on a trapezoidal block in what used to be the heart of Greenwich Village and is now more truly a province of imperial NYU—lives in one apartment, in one building, and works in a second building, just next door, so that his walk to work crosses no curbs, which are tricky for him. He turns 80 in July, is blind in one eye and made nearly so, in the other, by a cataract. Last year, he tripped over a pile of books in his office and broke a hip. He has also, to count only those injuries he’s detailed in his genre-eluding writing career—you catch brief striptease glimpses of memoir among case histories—two shattered legs, a replaced knee, and a collapsed foot. For a time, he was sure he would die in a motorcycle accident. He keeps a collection of canes by the door, taxonomized with colored rubber bands. “This is my John the Baptist staff,” he says, shaking the tallest one.

He is now probably the most famous, and most beloved, brain doctor at work today. He does not publish scientific papers, do research, or advance arguments about theoretical questions, but he has made his name as a teller of other people’s stories, stories that remind us that even in a scientific age, the world remains mysterious, especially when we set about examining ourselves. Nearly 30 years after The Man Who Mistook, we live in its Gnostic universe, in thrall to brain science—its strangeness and its poetry as much as its clinical insights. Evolutionary psychology is a scrapbook of fables said to be woven into the fabric of our minds, and an entire field of fiction has grown weedy with Sacksian curiosities: Ian McEwan writes a novel featuring De Clérambault’s syndrome and another about Huntington’s disease, Rivka Galchen about Capgras syndrome, Jonathan Lethem about Tourette’s, Mark Haddon inspired by autism. Marco Roth called the genre the “neuronovel,” and the British novelist A. S. Byatt has suggested we should start looking for the meaning of poetry in fMRI scans. And why not? We’re already looking for the meaning of life in them.

Once a conspicuous loner, Sacks is now a remarkably recognizable, avuncular public figure. He has been played by Robin Williams in Awakenings, in a performance that came seventeen years after the publication of Sacks’s book; satirized by Bill Murray in The Royal Tenenbaums; and lionized by Richard Powers in The Echo Maker. He is, himself, an even more curious character.

Sacks has been getting migraines, the subject of his first book, since the age of 3 or 4, accompanied always with visual hallucinations. (“I usually ignore it, but if it’s a peculiarly pretty one, I relish it,” he says.) These “hallucinations in the sane” are the main subject of Hallucinations, which also surveys drug-induced ones, which Sacks has also experienced. He has written about face-blindness, which he has, and place-blindness (difficulty remembering spaces), which he says he also has, and deafness, which he increasingly has. He lost his stereoscopic vision in 2006 from ocular melanoma, and he has written about that, too, in The Mind’s Eye, his eleventh book. He’s returned several times to the subject of his third book, A Leg to Stand On, which recounts his own experience of growing disassociated from one of his legs while it healed in a cast—a kind of reverse phantom-limb syndrome. “I’m an honorary Tourette’s because I tend to jerk,” he’s said. “I am also an honorary Asperger. And I’m an honorary bipolar. I suspect we all have a bit of everything.”

Sacks’s most notable problem, though, is what his friends tactfully call his “shyness,” and which he calls a “disease.” In his telling, his childhood was virtually friendless through middle adolescence; he doesn’t understand what people could possibly like about him; and he’s spent most of his adulthood in a state of acute, even paralytic loneliness, rescued only by work. “I had never been in a situation of such safe intimacy with other human beings,” he has said of the time ministering to the semi-catatonic patients of Awakenings.

“I once heard a radio program about people who’d been evacuated in the war as children, as I was,” Sacks says. “And one of the men there, who’d had rather a bad time, now seemed to be fine, but said he felt he was deficient in the three B’s: belief, belonging, and bonding. And I would say that a bit for myself. I’m a friendly guy, but there’s always a certain, almost uncrossable distance.” Later, a little sadly, he goes further. “I never initiate contact. It’s a little bit like some of my Parkinsonian patients, who can’t initiate movement but can respond to music or a thrown ball.”

He has been in psychoanalysis, continuously and with the same Freudian interlocutor, for 46 years—remarkable for a materialist neurologist. “We were both young men, and now we’re old men. There’s a longitudinal study for you,” he says. The two remain on formal terms: “He’s still Dr. Shengold, and I am still Dr. Sacks,” he says. “I think that a patient can become a friend, but that one shouldn’t be a doctor to a friend—there is a distance, which paradoxically allows closeness, as I feel with my own patients.”

Sacks says his shyness simply “doesn’t occur” in those interactions, which may be one reason he is so good with his patients and another reason he so loves them. In his work as a physician, the social landscape is unusually even-planed, for him and for them, and he has an uncanny ability to put his patients at ease—with sustained attention; curiosity and empathy; and a physician’s bag, stuffed with balls, a reflex hammer, and magazines, that could serve a clown. “Among other things, I’m a good and sometimes involuntary imitator,” Sacks says a little mischievously.

It is hard to resist the impression, when visiting him, that you are on a house call, in part because he routinely refers to himself as a “case.” Uncomfortable as it makes me to play doctor, I do take notes. His right eye is a boiling red, and his fly is left unzippered. He lifts up his pants to show the scar from that long-ago broken leg. Apologizing for having only one working hearing aid, he sits down, wedged between two special pillows, at cross-purposes to me: “I may seem to be turning away from you, but really I’m turning toward you.” Looking mostly at the floor just beyond his feet, he speaks at a deliberate pace, meandering from abstract questions on neurology to particular episodes and patients.

He moves in the opposite way when asked about himself, drifting into characterizations that present his own life at a safe distance. “I think there was probably a rather long lost period in which I functioned. I passed exams, I had a good memory, I was clever,” he says. He describes himself as a graphomaniac (having published now a dozen books, with just as many unpublished or discarded) and a babbler (“Things gush out of me, for better or for worse, incontinently”). But the feeling you get in his audience is of fastidious control, a man keeping the world at a safe distance—as though the wilted-flower persona is a genuine but therapeutic performance, benefiting his patients, his readers, and Sacks himself. “I’m sorry I’ve been a little evasive,” Sacks tells me at one point, offering one of many apologies for running off track. “But, what the hell, one has to be.”

His office is a converted two-bedroom and fans out from a central living room, now an open workspace for Sacks’s personal staff, who are, among the sea of people kept at arm’s length, those closest to him. One is Hailey Wojcik, a young woman with a dyed-pink streak in her hair who helps manage Sacks’s curiously active website (“As some of you asked after our last newsletter, how come the famously computer-illiterate Dr. Sacks has all this social media???”), and the other is Kate Edgar, a longtime collaborator who began as a sort of assistant and is now something like a best friend, first reader and editor, and stage manager. She is the dedicatee in Hallucinations, the one who deciphered his handwritten, water-soaked third manuscript; the one who accompanied him to the doctor when he learned he had cancer; and the one who abruptly cuts in when I ask Sacks if we might set up an additional meeting: “No, no, we have to keep him writing.”

To the right is Sacks’s room, where he’ll work longhand, see the occasional patient, and sometimes spend the night. To the left is a small seventies-era Formica kitchen, which holds a hobby collection of chemistry-themed kitchenware. When he offers me a glass of water, it was in a glass frosted with a periodic-table element. On the cabinets appear an array of crude black-and-white portraits, photocopy cutouts like you might see mounted to poster board at a science fair. They’re reproductions of drawings of Sacks’s “chemical heroes,” which he pasted up while working on his “memoir of a chemical boyhood,” Uncle Tungsten, and hasn’t touched in the decade since. “He’s really like a little boy, you know,” Edgar says.

Sacks grew up in “a large, rambling, untidy house” in Jewish northwest London just before the war. His father was a forbidding house-call-style G.P., devoted to conversational medicine, who read the Talmud at night, told Oliver to never trust a stethoscope, and three times won a fifteen-mile swimming race off the coast of the Isle of Wight. His mother worked at the Marie Curie Hospital and was among the first female surgeons in all of London.

Sacks would occasionally stumble into the surgical theater his parents shared elsewhere in the house—“a mystical room that emitted strange lights and sometimes noises and smells”—to discover his mother performing obstetric surgery. From time to time, she would show him “malformed fetuses,” some of them stillborn and others that she had drowned at birth—“Like a kitten,” she once said. Beginning at 11, Oliver was directed to dissect them; at 14, she brought him to the Royal Free Hospital and instructed him to autopsy part of the corpse of a girl his own age.

England was oppressive to Sacks—he’d later call it rigid and constricting, especially its medical culture. “I felt in a sense—it’s a terrible thing to say—that London was infested by my parents in various ways,” he tells me. “I imagine people might say to my parents, We saw your son in the delicatessen on Yom Kippur, We saw him in the swimming pool, or whatever. This is probably extremely unfair to them. But we all have to make a break, and for me I think it had to be to another country.”

On a 1960 trip to Canada at 27, in which he traveled by motorcycle, fought fires in British Columbia, and contemplated joining the Royal Canadian Air Force, he sent a one-word telegram back to England: staying. He chased his way to San Francisco, where sex, drugs, and liberated desire were just beginning to crack open the city—and made a kind of pilgrimage to the Jekyll-and-Hyde poet and gay bohemian antihero Thom Gunn.

Gunn had been a sort of idol for Sacks even before they’d met: “I felt unformed, like a fetus in comparison.” Sacks’s middle name is Wolf, and probably his favorite of Gunn’s poems is “Allegory of a Wolf Boy.” “This corresponded with a certain duplicity I felt in myself,” he wrote, “a need to have different selves for day and night. By day I would be the genial, white-coated Dr. Oliver Sacks, but at nightfall I would exchange my white coat for my motorbike leathers and, anonymous, wolflike, slip out of the hospital to rove the streets.”

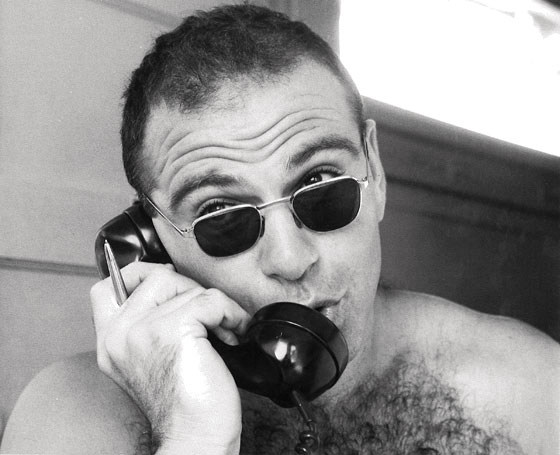

In 1962, he took a residency at UCLA, where he became a regular at Muscle Beach and set a California state weightlifting record with a 600-pound power lift: “I was known as Dr. Squat,” he says, “which rather pleased me.” And he continued to motorbike, riding solo and loaded with amphetamines as far as the Grand Canyon, stopping only for gas. One day, a patient paralyzed from the neck down and blind from neuromyelitis optica heard Sacks was a biker, and asked to come along for a ride; with the help of weightlifting friends, he abducted her from the hospital, strapped her against his own torso, and rode up and down Topanga Canyon.

Sacks calls these the “lost years,” and he writes in depth about them for the first time in Hallucinations. “I was nowhere and nothing in the sixties and very pessimistic about the future,” he tells me. “I was somehow on the periphery of things, or I felt I was. But there was, obviously, hunger for much more. And a lonely sort of compensation in drugs, lonely and often risky and dangerous.”

The drug memoir buried inside the book is eye-opening for anyone who knows the genial picture he’s cultivated for himself as a terminal wallflower. “I started with cannabis,” he writes, then moved on to LSD, morning-glory seeds, and a synthetic belladonna-like drug his friends from Muscle Beach recommended called Artane. “Just take twenty of them—you’ll still be in partial control,” they told him, and he did, then hallucinated so fully a visit from two friends that he cooked them an egg breakfast. When he realized his mistake, he ate all three plates, then heard his parents descending in a helicopter.

“The only time I feel free and happy is when I’m writing,” he tells me, using the present tense and speaking of the ferment of his life in the sixties as though it were the very recent past. “The idle times are dangerous for me. If I don’t take drugs, I brood or I lie in bed, or I eat too much,” he says. “I think Sherlock Holmes was very similar. When he wasn’t hot on the case, he would shoot up cocaine.” While back in London for his 32nd birthday, Sacks stole morphine and needles from his parents’ drug cabinet. “At a certain point, he just looked at himself in the mirror and said, ‘You’ve got to stop doing this,’ ” Weschler says. “ ‘If I keep this up, I’ll be dead in six months.’ ”

That self-intervention seems to be also, functionally, the end of his sex life—a near-total withdrawal from the social world. Sacks had described himself as having been “celibate” now for a period of decades, after moving to New York from California in 1965 when, he writes in Hallucinations, a “love affair had gone sour,” in what might be the first reference in his work to his own romantic life. “I lived alone, I’ve always lived alone,” he says. “I am, I believe the phrase is—one speaks of people as being ‘married to their work.’ ” The drugs had seemed to halfway solve the mind-body problem for him, and recovery meant a kind of relapse. “I’ve never, as they say, shared my life with anyone,” he says. “You’ll have to ask my analyst about that.”

New York in the mid-sixties was a psychoanalytic city, Freud in ascendance and Woody Allen in the wings. The arriviste Sacks was an exile in neurology, doubly an exile at an out-of-the-way “chronic hospital” in the Bronx, and triply an exile as a neurologist who found his discipline “mechanical” and “veterinary” and hoped to humanize it by importing lessons from psychoanalysis. Fifty years later, with Freud given way to psychopharmacology and neurology conquered by fMRI, he is just as much an outlier.

“Here, it’s been such an odd life,” Sacks says. “I remember one of my former professors from UCLA meeting me in 1977 and saying, ‘You have no position,’ ” he recalls. “But when he met me again in 1992, he said, ‘You’ve climbed to the top of the ladder.’ Now I think these were both wrong. I’ve never actually taken any notice of the ladder. I’ve skirted universities. I’ve been a sort of solo physician.”

Of course, there have been appointments (Beth Abraham, Albert Einstein, Columbia and, just this year, NYU) and honors (American Academies of Arts and Sciences and Arts and Letters, a Guggenheim fellowship, a position called “Columbia Artist” that the university created for him, funded in part by the Sainsbury supermarket family). But to hear Sacks tell it, his most important work has been inside nursing homes, most notably the Little Sisters of the Poor; even those doctors who’ve shared appointments with him at one or another area hospital say they could go years without seeing him on campus. “He’s in his own orbit,” one of them told me; another said he’d caught only a glimpse of Sacks, just once, during a neurology conference, in the swimming pool. These days, he sees a dwindling number of patients, referred by like-minded neurologists or by themselves, by letter, eager to commune with the legendary devotional doctor.

But to many psychiatrists and neurologists, devotion isn’t medicine, and even some of Sacks’s admirers acknowledge that his storyteller case history isn’t, actually, science. One called his work “liturgical,” another wondered whether he had ever actually improved the lives of his patients, and a third described his writing as diverting memoir. Many of his friends agree that he has made, at most, a trivial contribution to brain science.

When you ask Sacks about the extra-medical appeal of his writing, he takes it in stride, and tends to say the stories work as tributes to the marvelous adaptability of the human mind. “I think it’s important that nature can put a positive spin on so many awful-seeming situations,” he says. “People are scared of hallucinations—the very word immediately makes people aware of dementia or insanity. One of my more conscious motives is to provide some reassurance.”

“One of the key notions for Oliver is that the disease does not have the patient; the patient has the disease,” says Weschler, speaking especially of Sacks’s Awakenings experience at Beth Abraham—where “it was bumper cars of dereliction. And he would walk through and the place would just brighten up,” Weschler remembers. “The great moment of his genius was not giving those people the drugs; it was walking into that home for the incurable, that warehouse, and having the moral audacity to imagine that some of those patients were different from the other ones and that they were in fact alive.”

The writing was audacious from the very beginning. Most writing about the brain might as well have been about the colon, Sacks thought, it so missed the point. What he wanted to fashion was a “neurology of identity”—attentive to the nerve basis of disorders like face-blindness and phantom limb but focused much more sharply on the experience of affected patients, who built their identities in part through their battles with dysfunction. As he had done: a man eager to see his own life as something more than a footnote to a list of disorders and dysfunctions, who turned his congenital shyness and pathological inhibitions into a semi-shamanic clinical persona. We may be our brains, he wanted to say, but we also shape them as we backpack through the world with all our trinket-y neuroses. Neuroscience and evolutionary psychology offer insight, he suggested, but often at the cost of identity—we can find meaning in their discoveries, but only by acknowledging that one is primarily a species and only very trivially a person. In both his practice and his writing, he hoped to reverse that, to treat neurological disorder not as an extractable affliction but a mesmerizing, meaning-giving, and often benign peculiarity.

The result was an elaborate and idiosyncratic case-history archive, a folklore of mental disorder as rich and varied as Freud’s, but de-Freuded—wiped dry of any mention of sex and the implication that patients may be in some way responsible for their suffering. In fact, they seem often not to be suffering at all, but, with Sacks—like Sacks—marveling at their own disorders. “I am sometimes moved to wonder whether it may not be necessary to redefine the very concepts of ‘health’ and ‘disease,’ ” he wrote in An Anthropologist on Mars. “While one may be horrified by the ravages of developmental disorder or disease, one may sometimes see them as creative too.”

When I meet Sacks a second time, it is in his apartment, which overlooks a building-site stretch of Eighth Avenue and where he keeps a small farm of ferns, a particular love in his Victorian sideline of botany. He is squeezing me in before lunch with Robin Williams, now a friend who once rhapsodized about Sacks to Charlie Rose and whose cuddly portrait in Awakenings will surely, and spookily, outlive the standoffish doctor himself.

Sacks has now spent 50 years attending to patients damaged in ways that make it difficult for others, even doctors, to acknowledge their full personhood—those with Tourette’s, Asperger’s, the deaf, the blind, the hallucinatory and the self-disassociated. But perhaps his profoundest work has been with a population that goes nearly unnamed in his writing, though it supplies so many of the cases he writes about—and of which he himself is now, finally, truly a part. Neurological function declines over time, and many of the patients experiencing the most fantastical neurological symptoms are those typically dismissed, simply, as demented. Even as Sacks ages into the ranks of the very old, a remarkable number of his patients are older still than him; many of them approaching 100, birthdays he roots for. Often they persevere in the lonely carrels of nursing homes, navigating lives distorted by brain dysfunction in ways they’re terrified to acknowledge, worried they’ll be written off by physicians less sensitive than Sacks. He is like a village doctor, and the village is old age.

Nearing 80 and retreating from regular practice, he remains a hero to his patients and those suffering from similar disorders, and the way they worship him is a bracing suggestion that sometimes the dignity of real engagement can be more vital than therapy. “It teaches us that we are all flawed, and we find ways consistent with humanity to live with our illness, not just by popping pills but by somehow coming to terms with the illness,” says the chemist Roald Hoffmann, a Polish-born Holocaust refugee who’s become close with Sacks over the last fifteen years. “I think that we are all survivors.”

The night before, Sacks says, pushing a flyer across the broad worktable between us in his living room, he had been to a performance of Mozart’s Requiem by a chorus of medical students, and he remains entranced by it. “They were all young and dedicated, and I was carried away,” he says. “Thinking that I would like a performance of it in front of me as I was dying.”

We had talked quite a lot, in our earlier meeting, about his health, weight, and well-being, and it felt like he was doing me the favor of picking up the thread of that theme. “None of my inner organs are talking to me too much,” he said. “I’m aware of being what they call a cancer survivor, with luck I won’t hear from that.” Then he talked about his oldest friend, Eric Korn, an antiquarian bookseller in London now lost almost entirely to dementia, and paused for a long while remembering his shock at the death of Gunn, who died in 2004 at 74, “with an autopsy full of hard drugs.” Finally, he said, looking straight at me for the first time, “I don’t know whether there are any good ways to die.”