Even comedians—who rarely shut up—had to surrender whenever Patrice O’Neal began to talk. He’s the guy they would call on the long drive home from Magooby’s Joke House who loved to discuss—at length—whether Jay-Z would ever cheat on Beyoncé, or the various options for black reparations, or the best adjectives for different smells of pussy. He was a master at introducing subjects that you never even knew you had an opinion about—like whether you’d be willing to have sex with a girl who had no nose. Even though O’Neal was usually doing 90 percent of the talking, listening had the feel of conversation, in part because he was famously picky about whom he’d talk to, and in part because he always implicated you in his investigations. Whether the topic was crass or ridiculous, he demanded a response. The transformative power of the ugly truth was, for O’Neal, a form of grace.

If O’Neal was known for working his conversations offstage, he was equally well known for taking big risks with his audiences. “If you watched Patrice, all his shows were different and he didn’t write any of his material down,” says Bill Burr, a comic who came up with him in Boston. “He got to it in a new way every night. As long as I knew him, he was always working on trying to attain a level of freedom onstage where he could just go up there and talk to the crowd. To me, that was the Pryor school of stand-up comedy.” Of the many things O’Neal’s peers admired about his performances—the assertions he got away with, the sly surprise of his punch lines, the seamlessness with which he skated between warmth and disgust—what excited them most was the way his shows built as his attention moved among his listeners, sparking off their fears and desires and stirring them up.

“When you question a lot, you are wrong a lot—so wrong—but he’d present the case like a champion,” says Keith Robinson, a comedian and former roommate. “I’m arguing, and at the same time thinking, How this dude is working this!” O’Neal was always maneuvering to make room for the man he was still discovering himself to be—a seeker with competing appetites and sorrows; a half-domesticated feminist super-misogynist; an iconoclastic black man who defended the freedom of white racists on Fox News; a brilliant 325-pound jock philosopher from the hood whose favorite books were Sun Tzu’s The Art of War and Skinny Bitch: A No-Nonsense, Tough-Love Guide for Savvy Girls Who Want to Stop Eating Crap and Start Looking Fabulous!

“He was an artful dodger who kept researching himself,” says Robinson. And he expected others to make the same effort. His fiancée, Vondecarlo Brown, said it wasn’t unusual for him to lay into a cashier at Marshalls about her bad attitude; Brown would return from her shopping 40 minutes later to find the duo strategizing about ways the cashier might pursue her dreams. Talking led to what Patrice called “the reveal”—whatever tender or humiliating fact an honest conversation might unearth. Civilians didn’t always have the stomach for it, but comedians usually appreciated the insight. As comic Amy Schumer explained, “The only things he would say were things I didn’t see about myself.”

I’d been researching a book on stand-up for years, and people kept telling me I needed to speak with Patrice, but I always found a reason to put it off. To begin with, his reputation preceded him. He was six-foot-five, extremely loud, a bully, and an expert at leveraging white guilt. Once, at the HBO offices, I overheard his blowtorch of invective when noise in the lobby interrupted his meeting. He had reduced Lisa Lampanelli, an insult comic, to tears. Last year, we finally exchanged numbers, after which he casually eviscerated a young publicist nearby (“Shut your hole,” he said, with a purity of contempt that was striking, even though I was a comedy survivor by then). All of this convinced me that I needed more preparation. I never pursued Patrice O’Neal, and then he was dead.

This past December, at the Park Avenue Christian Church’s funeral for Patrice Lumumba Malcolm O’Neal, the comedians sat quietly. Some wore suits. Others spruced up in their own ways—baseball hats clenched in hands, T-shirts tucked in, slacks instead of jeans. Chris Rock and Kevin Hart wore sneakers, but they were there, along with Wanda Sykes and Artie Lange. Headliners spend a lot of time on the road; it was unusual to see so many of them gathered in one place. In the dim church light, they looked especially wan.

A pro who had known O’Neal for about twenty years later confessed that he’d had to work up the courage to make an appearance because he could hear Patrice’s voice booming, “What the fuck are you doing here?” Another stayed home because he imagined Patrice rising from the casket to lob a similar rebuke. O’Neal would have enjoyed the discomfort—discomfort was one of his favorite tools. At the same time, he would have appreciated the consideration; he gave serious thought to when and where he chose to show up.

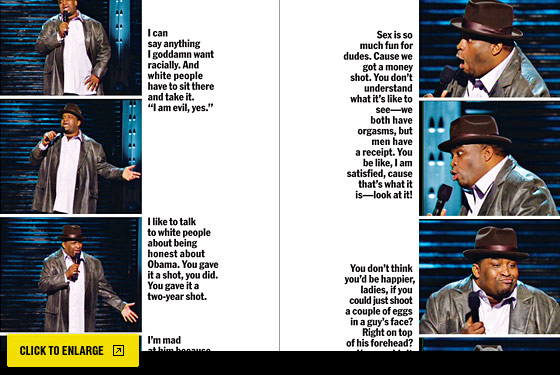

Patrice O’Neal’s Socratic Method: Thecomedian holds forth in two memorable riffs recorded the yearbefore he died.

Jim Norton stood. The third mike of radio’s “The Opie & Anthony Show,” Norton had clocked in thousands of hours of conversation with Patrice both on and off the air. They’d toured together and done TV shows together and gotten prostitutes together. Norton also heard Patrice ridiculing him as he approached the lectern—“Shut up!”—but he found the familiar blast of insult reassuring. For the nearly six weeks that Patrice had been in a coma following a stroke last fall, the “O&A” show had become a cross between a hospital waiting room and a coffee shop. Comedians kept stopping by and calling in with their favorite Patrice stories; after he died, the stories continued to pour in. Comics spoke about the thrill of witnessing someone’s first takedown by Patrice and the suitcase full of dildos he brought hookers on his trips to Brazil. They also rehashed the highlights of his bridge-burning career—his lousy attitude when he auditioned for Chris Rock; his unwillingness to keep his schedule open for Spike Lee; his refusal to travel to L.A. for additional work on The Office, where he had a recurring role.

At the church, Norton read a few of the hundreds of e-mails sent in by “O&A” listeners. One wrote, “I never had someone make me laugh so hard, while saying things I couldn’t agree with less.” Another woman introduced herself as a friend of Eddie Brill’s, the former booker for David Letterman, who’d met Patrice after he opened for Denis Leary at Carnegie Hall in 2004. He’d stared at her nipples and said, “Well, at least one of them is happy to see me!” The woman explained that she was undergoing treatment for breast cancer. When Patrice seemed to doubt her, she found herself flashing him to prove it; he had roared with laughter and enveloped her in a bear hug. When Norton had visited Patrice in the hospital, he told him how many people were asking after him. “Of course,” said Norton, “he couldn’t respond, and I realized, in all the years I’ve known him, this is the first time I’ve ever dominated a conversation with Patrice.”

Colin Quinn went next. “That was very nice, what Jim said,” he began somberly. Then he paused, and the comics, suddenly alert, sat up a bit straighter for what they hoped was coming. “ ‘Eddie Brill’s a friend?’ Why would you include that? You irrelevant idiot.” People laughed and shifted in the pews; they were loosening up. Quinn recalled how even on his own TV show, Tough Crowd With Colin Quinn, the network frequently gave him can-you-shut-up-Patrice? notes. “You couldn’t shut Patrice up any more than you could shut off a river,” he said. “Patrice is the only guy I can imagine trying to meet God as an equal. If I could somehow be looking at him in Heaven right now, and watched him meet God, I know I’d be thinking the same thing everybody else would be thinking. ‘Uh-oh, God shouldn’t have said that. Now he’s going to get hammered by Patrice.’ ”

Other performances followed. Wil Sylvince, O’Neal’s longtime roommate, spoke about how Patrice disabused him of stereotypes of overweight men: He didn’t smell, didn’t leave food lying around, and always had women. Kevin Hart, who now fills stadiums, remembered a night at the Comedy Cellar when Patrice and the other big-shot comics tossed telephone books at him. As Robert Kelly approached the podium, he imagined what Patrice would have said—“Speak from your heart, asshole!”—so he did. Rich Vos followed, scoring points off both Kelly and “Lil Kev,” then preempting ridicule about his own stalled career. “I’ll be selling my DVDs and CDs on the church steps after the service,” he said, waiting a beat before adding, “just as Patrice would have wanted it.” O’Neal, a terrible self-promoter, hated merchandise.

The funeral was in many ways just the kind of room Patrice liked to work in—with people he loved, stripping away one another’s pretensions to get to a more honest place, and ultimately on his terms. Not surprisingly, this dynamic had eluded him in Hollywood, and he had repeatedly tried to re-create it on cable, the web, and radio. He operated in what a former manager called “Patrice time”—at his own pace and on the assumption that others would eventually catch up. At one point, he’d come up with an idea for a show: The Patrice O’Neal Show, Starring Other People. The Park Avenue Christian Church was as close as he was going to get, but he wasn’t there to see it.

Patrice was not regarded as a man of many secrets. No topic seemed off-limits: his laziness; his loneliness; his threesomes; he’d even discussed his terror of prison, where he’d spent time on a statutory-rape conviction when he was a teenager. But many of the comics at the funeral were caught off-guard when Vondecarlo’s 12-year-old daughter, Aymilyon, in her bright-pink dress and rhinestone headband, spoke without a trace of irony about the man she liked to call Mr. P. It was clear from her description of the things he’d taught her—to try new things, to laugh when she was angry, and to argue for her opinion—that she, too, had known the same Patrice. This surprise guest was a classic Patrice closer: evidence that required you to reconsider everything that came before it. At a funeral that resembled a roast, the reveal wasn’t the mention of sex tourism or a breast-cancer flasher, but that he had been a father, too.

By November 2010, when O’Neal finally taped his first hour-long special, Elephant in the Room, at NYU, his health was failing and he knew his time was running out, but he acted as though he had plenty. He looked over the assembled and smiled his charmingly demonic gap-toothed grin. He didn’t open with a foolproof bit. Instead, he warmly objectified a black woman in his line of sight. “I am thanking one in particular pair of titties,” he said, delighting in another eyeful, then making a point of the televised context of the show: “Thank you, audience coordinator, for putting those titties up in the front row.” Then he grunted. So begins the Comedy Central special that he hoped would broaden his appeal.

He next bestows his approval on a black man’s date: “Congratulations to you, my friend!” he says. “Look at that white woman you’re with!” He invites the audience to consider this fine specimen: “Black women get mad at that. But that is top-shelf white woman right there.” He’s arranging and rearranging members of the audience on various sides of an argument that they don’t quite know they’re in yet.

“You know how you tell how pretty a white woman is? The value?” he asks. “You look at her and then wonder how long they would look for her if she was missing.” He points to the evidence already at hand: “C’mon, take a look. Take a look! Look at this! Look!” Everyone is laughing, but you can hear uneasiness. He appeases it by enlisting a black woman to exploit the prejudices he’s now juggling. “I saw you look mad, sweetie,” he says as if he’s talking only to her. “If you was missing, how long you think they would look?” He reports back to the crowd, mimicking her mournful shrug. He lets the sorry truth land: “White woman’s life is valuable.” He then asks the audience to help him remember the point he was originally getting at: “What’s his name—Joran van der Sloot? We find out he was a serial kill—man, he kills women, that’s what he do,” he says. “What’s the girl in Aruba?”

“Natalee Holloway!” people shout out.

“But the one—he just killed the girl in Peru, what’s her name?”

Silence.

“Exactly!” he says. The audience cracks up and breaks into applause, simultaneously chagrined and excited to have sprung that trap he’s set for them.

All this, he explains, is why he’s taking a white baby along when he goes sailing, just in case the boat sinks, to be sure that someone will come looking for him: “I’ma dress the baby real white, too. I’ma put sweatpants on it, and a pair of Ugg boots, and I’ma take a picture,” he says, snapping the photo with his imaginary iPhone. “ ‘If you don’t come get me, this white baby going down!’ ”

O’Neal believed that stand-up—if it was any good—had to take prisoners, that it was always at someone’s expense. And if anybody was going to be uncomfortable, it wasn’t going to be him.

The only place Patrice O’Neal was ever comfortably second-seated was during the early years, as a passenger in other comics’ cars—as long as they were going his way. Bill Burr took him to the open mike at Nick’s Comedy Stop in his red Ford Ranger; Robert Kelly drove him in his gray Nissan 280-ZX to the one at Stitches, another Boston club. Owing to his size, O’Neal would have to move his leg whenever Kelly would shift into fifth gear. O’Neal preferred Dane Cook’s turquoise Lincoln Town Car with the whitewall tires—young bucks, Pimp A and Pimp B. But their coolness was just a pose. “There was a lot of sensitivity,” says Cook. “I remember an eager Patrice.”

O’Neal grew up in Roxbury, Massachusetts, in a private house across from the projects, and he attended a suburban school, mostly white. At West Roxbury High, he played football well enough to earn an athletic scholarship, which he declined in order to study the performing arts at Northeastern. He worked as a bouncer at the Comedy Connection before climbing onstage—and then quickly went from holding doors for other comics to being one of the most promising among them.

O’Neal got laughs faster than most beginners do, but he was more interested in how stand-up could work for him. Gary Gulman still remembers one surefire bit of Patrice’s (“I’m the leader of the fat people, I’m Malcolm XXL”). “Some guys would hold on to that joke for their entire career. It’d be the name of their album and special, they’d have T-shirts,” Gulman says. “That was not his thing.” O’Neal allowed himself to have moods onstage. He’d change the wording of a perfect sequence from one night to the next, explaining, “I want to say it how I mean it, and maybe I meant it differently than I did yesterday.” Bill Burr recalls, “Patrice was like a musician, trying to free himself.”

Dane Cook remembers one discussion they had about people-pleasing. Patrice wondered if the desire to be liked onstage might be coming from the need to protect a belief in oneself as a nice guy offstage. What if you weren’t that guy at all?

For comics to truly realize themselves as performers, they must learn to traffic in their vulnerabilities, but the stakes were particularly high for Patrice. By the time he was 17, he had been convicted of a sex crime against a white woman—a stigma that so scarred him that he didn’t discuss it publicly for decades. According to his story, he and some friends met up with two 15-year-old girls and they ended up having sex together. The boys bragged about the encounter, and another boy used the gossip to blackmail the white girl for a blow job. As rumors spread, the girl started saying she’d been raped—first by her blackmailer, then by the original group. O’Neal and his best friend, the only two who admitted having sex, were convicted of statutory rape, for which they served 60 days in an assessment center that summer.

O’Neal would remain haunted by the swiftness with which—on the word of a woman—his identity could be obliterated by a stereotype. In the 2005 “O&A” interview where he went public with the experience, O’Neal noted that there was no room for the uncomfortable truth in the story: white girls who want to have sex with black boys. What had saved him was that the girl, too, was unimportant in the wider world: “I am a giant nigger in Boston. If this girl had been the mayor’s daughter, if she had been some white girl out there doing some George Bush’s daughter shit, and it came out that she gave all these niggers some pussy? You wouldn’t know me.”

The interconnections among victimization, accountability, race, and desire proved to be rich imaginative terrain. In one popular early bit about littering, he says, “I’m afraid if I toss a can of soda over my shoulder, it will fly over a bush and land on some dead white woman’s head, with my fingerprints on the can. Now I’m the Pepsi Cola Rapist—’cause I’m lazy.” He explained that he always made sure to create a ready-made paper-trail alibi for himself, buying something every fifteen minutes and demanding a time-stamped receipt.

O’Neal’s work fought back not by running from the stereotypes but by refashioning them and trying them on, to see what fit—and what didn’t—and he coaxed his audiences to do the same. Could women really deny that they wore sexy clothing at work to turn men on? Didn’t all men have “rape-y” thoughts? O’Neal was determined that his comedy be something scary and exciting that he and the audience were creating together—they wouldn’t be able to pretend they hadn’t been a part of it afterward.

He found his ideal audience in 2002 at the comedians’ table at the Comedy Cellar in New York. The Cellar is a workout club where pros try out material in fifteen-minute sets. Before and after going on, they often hung around the table in the back of the restaurant upstairs—gossiping and eating and arguing. Colin Quinn compared it to the Round Table at the Algonquin—if the table were a mosh pit. “Ripping down is love in comedy,” says Dane Cook. “It can be very cold. It’s a weird hazing that comics do to keep each other on point.”

“We teased him forever,” says Keith Robinson. “We beat him out of himself.” But Patrice gave as good as he got, then gave some more. “When Patrice was around, you had to raise your game,” says Rich Vos. Bill Burr prepared for even casual encounters with his old friend: “I’d come up with a dozen insults, do two or three, and he’d swat you to the ground.”

The conversation became the genesis for Quinn’s show, Tough Crowd. Patrice was one of the regulars from the start. Quinn would introduce topics—race, religion, sex, politics—and the other comics would bat them around. The stand-up Laurie Kilmartin, who wrote for the show, admired O’Neal’s swagger—to get a word in “you just had to wait for him to run out of breath,” she says—but she admired his range even more. “He had the ability to go other places other comics couldn’t go because he didn’t show a lot of bitterness, he showed a lot of curiosity,” she says. “He would keep the ball in the air.”

After two seasons, Comedy Central canceled the show. For O’Neal, its ideal conditions would prove hard to replicate: work that felt like play, raised his visibility, and paid him to be himself. By this time, however, O’Neal had assembled a respectable résumé: the festivals (Aspen, Montreal); guest spots on television (Chappelle’s Show, Arrested Development, and more); and movies (25th Hour, Head of State). The half-hour specials came easily: Showtime, Comedy Central, HBO. The development deals didn’t pan out, but that wasn’t unusual. Meanwhile, the archive of Patrice stories grew—the lucrative offers shunned, the budgets stretched by his time-sucking monologues, the verbal pummeling of executives.

He was also making enemies among his peers. The less frequent guests on Tough Crowd had found him bullying. At the Cellar, he derided Lisa Lampanelli so viciously that she avoided the table altogether. “I wasted more tears on this guy than an ex-boyfriend,” she told me. “It takes a coward to be a fucking asshole in real life,” she said, before repeating a remark made recently by a New York club owner: “Now I’m going to have to say I liked him because he’s dead?”

But likability didn’t rank high on Patrice’s list of values. In 2006, he was invited to host VH1’s Web Junk 20, a video-countdown show. “I don’t do ‘Hurry up,’ ” he said on the first day of production, and proceeded to abuse everyone on the set. During the shoots for subsequent episodes, the allotted four hours frequently turned to eight. The crew sometimes laughed so hard that they felt physically sick.

One career strategy in stand-up is that TV brings you popularity, which brings you freedom to do your real work. But Web Junk fans who came to his live performances found an angry Socrates holding forth on race and sex, driving people from the room on a regular basis. What happened to the funny black guy wisecracking about masturbating-cat videos? In 2007, he declined to renew for a third season—even when VH1 offered to quadruple his salary.

Patrice wasn’t primarily after money; he hoped to inspire some kind of personal reckoning. “And so?” was a favorite retort. “Fix yourself,” he’d say. “You’ll feel better, you’ll see.” He didn’t make it easy. Dante Nero, who sometimes opened for him, recalled one college gig when a young woman yelled, “Say something funny!” during one of Patrice’s philosophical disquisitions. “You didn’t hear anyone else laughing?” O’Neal began. “Is it because you weren’t laughing? You the type of person who wants everyone to be miserable if you’re miserable?” Then he turned to her friends: “Why do you hang out with her?” The girl stood up to leave, demanding her boyfriend join her, but he sat there, frozen, and O’Neal zeroed in on him—as an ally. “If you stay, it’ll be over,” O’Neal said encouragingly. “Ride it out.” The audience started to weigh in. The girl began to cry.

“Patrice kept going and going, twisting the knife,” said Nero. “I give them a piece of candy to get it down. But Patrice thought, ‘It got to be Buckley’s’ ”—the cough syrup—“ ‘a nasty lesson should taste nasty, and you don’t get a piece of candy afterward.’ ” The mixed metaphors here are telling; whether O’Neal was a healer or an assassin could be difficult to say. Between 2006 and 2008, he ministered to the lovelorn on “The Black Philip Show”—originally subtitled “Bitch Management”—which he co-hosted with Nero on SiriusXM. On this send-up of Dr. Phil, his advice is by turns poetic and appalling. One moment Patrice is patiently explaining to a heartbroken 20-year-old that he needs to sort through his pain because “sorrow carries over to the next relationship,” and the next he’s berating a female caller for what he considers her inflated sense of self: “Tell me why I shouldn’t call you a bitch, bitch?” Throughout, his conviction that men must fight to figure out how to meet their needs is blisteringly clear.

Vondecarlo, who is a singer, compares their courtship to the way he broke down an audience. In this case, the set lasted nearly ten years. “He said I suffered from Pretty Girl Syndrome,” she says. O’Neal accused her of treating her hotness as a substitute for personality; he refused to sleep with her for months. On “O&A,” the porn stars and Penthouse Pets dreaded being booked with Patrice. He’d badger them for not having opinions and zoom in on every little thing—including a tiny pimple on one girl’s butt.

Gino Tomac, O’Neal’s writing partner, learned that simply agreeing didn’t let him off the hook: He had to prove he’d reckoned with Patrice’s reasoning. Tomac remembers an endless treatise on the precise differences between “yep” and “yeah” and “yes.” The writer described the collaborative process as “brutal” and “painful” and “torture.” He also said he’d give anything for the chance to do it again. Their 2007 web series, “The Patrice O’Neal Show, Coming Soon!” couldn’t find a sponsor because there wasn’t a group it didn’t offend.

In 2010, Neal Brennan, the co-creator of Chappelle’s Show, wrote a pilot with a character inspired by Patrice—harsh and philosophical, in a warm way. Brennan phoned him and cut to the chase: “Are you going to be a dick?”

“How you going to be asking me if I’m going to be a dick?” Patrice said. Then he launched into a two-hour meditation on his philosophy of being a dick. “Neal,” Patrice said finally, “I can’t promise you that I won’t be a dick.”

Three remarkable interviews with fellow comedians Ron Bennington, Paul Provenza, and Marc Maron between 2007 and 2010 map O’Neal’s empathetic imagination at work. They also document a middle-aged comic original taking stock of his creative needs in a business that had, for the most part, failed to meet him at his best. He knew he was enormously talented and that his stand-up was important. He remained both wounded and mystified by his irrelevance in the broader culture, and he also realized he had adjustments to make. He apologized to a few people in the industry he felt he’d treated badly and decided not to take on work he’d sabotage, then recommitted to his own course, as he had always done. “I’m not finished offending people,” he said. “I’ll be an unedited racist, unedited sexist, piece of garbage till I die.”

The respect of other comedians had sustained him during the difficult times: “They’ll tell the truth. Even if they don’t like me as a person, my worst enemy won’t say I suck as a comic.” But he had plenty to say about comedians who cared more about being liked than committing to their particular point of view: “Do you have a life philosophy? Do you have anything that says goddamn ethic? Any ethic, you piece of shit? If you don’t, don’t talk to me. I don’t even have to say sheep.”

O’Neal was also trying to reconnect with the purity of his early years in stand-up—when the crowd wasn’t the means to some bigger end but a group of other human beings in the room. “I am trying to work my way through all these obstacles to get back to the audience,” he said.

By 2011, O’Neal’s new approach was bearing fruit: He finally taped a Comedy Central hour, which he promoted on Jimmy Fallon’s show—his first network appearance in four years. He also recorded his first CD. The business was changing, slightly, too—evidenced by FX’s partnership with Louis C.K. John Landgraf, the network’s president, during his first meeting with O’Neal, gave him a development deal on the spot. “I didn’t want to cast Patrice in a sitcom,” said Landgraf. “I wanted to create The Patrice O’Neal Show. It took him a while to believe we meant it.” FX didn’t bail after O’Neal rejected their first script. Perhaps equally significant, Patrice didn’t bail when they passed on the draft he and Gino Tomac came up with.

But if O’Neal’s star was rising again, his health, which had never been good, was in jeopardy. He tried juicing and being a vegan, but could not lose the weight. Vondecarlo regularly woke during the night to check that he was breathing. He spoke to his friends of losing interest in sex, and of the fear of losing her because of it. “I’m 40,” he’d said onstage, “and that’s young in everyone-else years, but in black years—high blood pressure, diabetes—if you did a black-to-white-life ratio, I’m a 177-year-old.”

The Comedy Central roasts are cheesy, pretaped affairs with a mixture of top-flight comics, hacks, and faltering celebrities, but they can substantially boost a comic’s visibility. Patrice hadn’t done one since the salad days of Tough Crowd; he wasn’t interested in roasting people he didn’t know. But that summer, O’Neal agreed to do the Charlie Sheen roast because he respected Sheen for going against the machine, and he wanted to tell him in the way that held the most meaning for him—face-to-face.

No one liked to follow Patrice, so he was last in the lineup, as usual. When the moment finally came for O’Neal to perform, the comedians watching understood what it meant when he looked at his set list and shook his head. Patrice was going to be Patrice again—this time in front of millions of viewers. By the time he got up to speak, he had been in the room for three hours and had to address what was actually going on.

“I had all this planned shit, but I didn’t know William Shatner was going to be a quasi—like an old racist man,” he started, each insult bringing with it another nuance of his take on the differences between celebrity and true performance: He bemoaned the fact that Mike Tyson no longer scared white people; ridiculed Jackass’s Steve-O’s cynical use of his own recovery; and sent Anthony Jeselnik, an up-and-comer, back to his booster seat. “He had to go from his guts,” recalled Robert Kelly, amped up all over again by the memory of how well Patrice had done. “You take away the script from any other comic—take away the piece of paper—they’re finished! They’re you! They are anybody else!”

It’s one of the highs that stand-up can deliver—making the most of what you’ve been given, bringing it to bear in the here and now, and showing people what you’ve got—which, for Patrice, was the searing need for people to own up to themselves. Even in the edited version that aired, the shock in the room is palpable. Patrice was incredulous. “How can I be too mean after all this shit?” he asked. In Patrice’s view, brutal honesty was a form of love, and roasting as close as comedy got to Utopia. How could the audience not be grateful for the gift of it? A lot of the evening’s earlier insults hadn’t even been true.

Everyone agreed that Patrice had killed; he was pleased but not surprised. “What I been practicing my whole life is to be okay in the moment of possible failure,” he said after the show aired. “I came through, for myself.”

William Shatner later told me that after the taping, he and his wife ran into Patrice at the garage and talked about his diabetes as they waited for the valet. “It was a strange place to have a conversation about life and death,” Shatner said, “but it was presaged by his clarity at the roast.”

Shatner and his wife reminded him that diabetes wasn’t like cancer and there were things he could do to save himself. Patrice was moved—these two old white people sharing their knowledge. At the end of the conversation, the three of them cried. “He knew that he was dying, that he was a dying man, and in a way, he wanted to die,” said Shatner. “That’s what I saw. That’s why we cried.”

In the last interview he ever did, weeks before the stroke that eventually killed him, O’Neal spoke to fellow comedian Jay Mohr about the business, which was playing heavily on his mind again. His special hadn’t changed anything much, and the heat from the roast hadn’t been transformative, other than helping him finally sell out a weekend at Carolines. He had another meeting with FX—now about an animated series, but the project that most appealed to him was one that required his friends coming to him—to his condo in New Jersey, where he would interview them. Mohr urged him to agree to the next roast, but O’Neal knew the moment was singular and that it was done. What about a podcast? Patrice didn’t want to communicate in a virtual reality. He needed the audience’s energy. “I’m dying inside,” he told Mohr. “But never onstage.”

Mr. P, the only live album O’Neal ever recorded, took place at the DC Improv on a Friday night in the spring of 2011 and was released this February, two months after his death. Many working comics believe it will rank as one of the top 25 comedy albums of all time. He loved performing in D.C., where people heard about the show the way he most respected—by word-of-mouth. If, as O’Neal said, what fed your integrity was your journey to find your people, he found them that night at the Improv.

Melba Davis, the manager of the club, was there; she scheduled herself to work whenever Patrice performed. She loved talking to him backstage and watching him continue the conversation onstage—whether he was chiding her for not having sex while she still could, or taunting the women at the front table, who were acting like they didn’t need men. “His how-dare-he was exciting,” she said. “He demanded you go with him.”

But O’Neal believed that he was only as good as the crowd made him, and that night, they were willing to be taken as far as he wanted to go. On the CD, the laughter keeps getting louder, and Patrice’s own laugh is as loud as anyone’s. After a gorgeous bit on revolutionary leaders, he discovers that a young black man in the crowd is named Tolu: You can feel the terrible thrill move through the audience at what’s coming next—O’Neal seizing the reveal, hilariously and mercilessly riffing on the burden of an African name that’s been chosen by somebody else. It’s a spontaneous moment, full of anger and love, and as close as you can get to the conversation you never had with the comedian Patrice Lumumba Malcolm O’Neal.

This possibility of communion is what live stand-up gave back to Patrice. He’d explained it to Mohr this way: “The audience has to give when they are in the crowd. When I do shows and I see you, I know that you’re giving. Even if you’re not giving, I’m going to fucking see you.”

From the Archives

O’Neal’s New York Diet