On a sweltering, oppressively humid August afternoon in Brooklyn, as some poor lady across the street yells at her shirtless son to getbackoverhereyou while pushing a stroller through the front doors of the Applebee’s across from the Atlantic Center, as a construction worker blankly looks on while gnawing on a bagel sandwich and smoking a cigarette, as a half-clothed homeless man pours a bottle of some indeterminate liquid on his head to stay cool … it’s impossible to believe that Jay-Z is going to be here in about a month and a half. This place is about as glamorous as stepping in chewing gum on the subway platform.

The construction on Barclays Center has been going 24/7 for about a month now to prepare for the big opening night, September 28, the first of eight Jay-Z concerts to open up the Brooklyn building, but all told, it’s pretty quiet this Sunday. It’s so hot that most of the laborers are sitting around dumping water on each other, the massive crane above the structure’s oval roof is idle, and the Modell’s across the street, with all the Brooklyn Nets gear, is mostly empty and sad. (Though not nearly as sad as the lonely shelf of Linsanity jerseys.) There are people bustling around, through Buffalo Wild Wings and Men’s Wearhouse and that terrifying Target, in a fashion more Times Square than Downtown Brooklyn. There have been complaints about Barclays Center construction, but the much larger issue is the narrowing of streets, turning that gnarled Fourth Avenue–Flatbush Avenue–Atlantic Avenue intersection into a sweaty game of urban Twister.

Other than the Modell’s—the official sporting-goods retailer of the Brooklyn Nets, and the spot where the team debuted its spiffy new circular-B logo back in April—the only signs that the neighborhood is preparing for the franchise’s arrival are a billboard featuring the team’s newly acquired shooting guard Joe Johnson (not, notably, their prime off-season target, Dwight Howard, who was recently traded to the Los Angeles Lakers), proclaiming HELLO BROOKLYN, and a corporate rental building on Sixth Avenue and Atlantic called Atlantic Terrace. There’s a sign on the side of the building from Ingram & Hebron Realty, the brokers. WANTED, it says. SPORTS BAR/LOUNGE. CLOTHING. MARKETPLACE. FITNESS. HEALTHCARE. RESTAURANT. 2,000–11,200 SFT AVAILABLE. WE WANT TO HEAR ABOUT YOUR USE! The retail space right now sits empty.

The sides of Barclays Center, with their imposing, metallic, strangely toaster-looking exteriors, are essentially completed. It’s the entrance that still needs the most work. The building’s giant overhang, an immense oculus, is coming together to the point that you can see where the LCD display screen that will flash tonight: heat at nets is going to go. The new subway portal, with an escalator from the Atlantic Avenue–Flatbush Avenue megastation to the building’s main entrance plaza, has taken shape; had I been able to sneak past the security guard at the gate of the construction site, I might have been able to run down its stairs. I just would have had to stomp through a lot of mud to get there. One thing you can see, though, from the street, one thing that’s definitely done: the opulent chandeliers from one of the stadium’s swankier luxury suites. The space looks amazing, and it’s not even Barclays Center’s most famous feature. That would be the Jay-Z–inspired Champagne room called the Vault. The Vault is the exclusive club within the exclusive club that has eleven suites that cost $550,000 a year (with a three-year minimum purchase) but have no view of the court. (You do get eight tickets in the first ten rows for every Barclays Center event, were you to choose to actually leave your suite and use them.) Those luxury chandeliers, you can see them from the street. They’re ready.

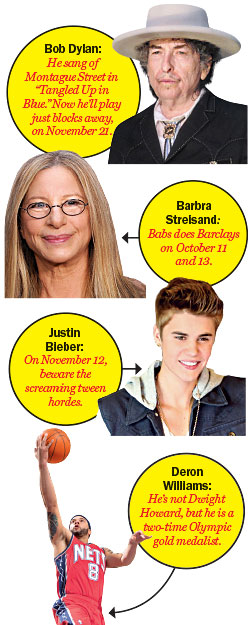

The Atlantic Yards–Barclays Center project has been so tortured, controversial, drawn-out, and infuriating in the making that it’s easy to forget that the building itself is real: that the project is not just happening, it’s almost completed. The staff of the Brooklyn (that’s right, Brooklyn) Nets has already moved into spiffy offices in Metrotech (just two buildings down from the much-maligned real-estate developer Bruce Ratner’s offices in the complex he built), and the arena itself is already open for private tours to prospective luxury-box season-ticket holders and sponsors. You can already buy tickets to see Barbra Streisand, Bob Dylan, or Justin Bieber. This is no longer a public debate, or a public outrage, or a theoretical construct, or an example of private might overcoming public interest. That battle is over, and Bruce Ratner won it. It is now part of the new Brooklyn reality. It is the centerpiece of how the borough, and the city, will be seen for generations to come. It is undeniably here.

So, now what?

Controversial real-esate developer Bruce Ratner owns 55 percent of Barclays Center and 20 percent of the Brooklyn Nets. Russian industrial magnate Mikhail Prokhorov owns 80 percent of the Nets and 45 percent of Barclays Center. The rapper Jay-Z owns only a fraction of one percent of both operations, but provides A-list star power.Photo: Terrence Jennings/Sipa Press/Newscom (Jay-Z, Ratner); Simon Dawson/Bloomberg via Getty Images (Prokhorov)

Standing on the corner of Dean Street and Atlantic Avenue last November, under a massive crane (the operator winked at us when we walked past him), Bruce Ratner ponders his creation. Ratner knows what everyone thinks of him. He’s the guy who doesn’t even like basketball and simply used public sentiment for a sports franchise in Brooklyn to line his pockets with public funds and residential high-rises that may or may not ever be built. He’s Bruce Ratner: He’s the bad guy. These are not even claims Ratner denies, at least not all that strongly. He certainly admits to not being a basketball fan, though he will later tell me he can’t wait to see “Barbra and Dylan.” (He’s less sure about Bieber.) Ratner doesn’t worry about his personal legacy; once, during another meeting, he pointed to famous buildings nearby and noted that no one knows the names of the people who built them. The world is a “long, big place,” he said. One hundred years from now, “Brooklyn is going to be an epicenter of this country, and this place will be at the middle of that. No one will care what we had to do to make it happen.”

Ratner’s vision for Barclays Center is, if nothing else, grand. What he and his Avengers-style business partners—Nets majority owner and Russian industrial magnate Mikhail Prokhorov and partial Nets owner (one fifteenth of one percent, anyway) and megawatt franchise ambassador Jay-Z—imagine is nothing less than the literal and symbolic centerpiece of a new, 21st-century Brooklyn, one that’s as gleaming and modern as the shiny new structure itself. “People will know this arena from Brooklyn, and people will know Brooklyn from this arena,” Ratner says. He describes the project as “another leap forward” for the borough.

At one of the countless local public events that Ratner and his organization have held over the past two years (the woman who cuts my hair in Brooklyn Heights says that her salon has been visited by a Nets representative “at least three times”), ubiquitous Brooklyn borough president Marty Markowitz started talking about the Brooklyn Dodgers. Every time Markowitz is at a Nets event, he brings up the Dodgers and Ebbets Field and bringing sports “back to Brooklyn, where they belong!” The Ebbets Field connection is obviously vital for Markowitz, who was 12 years old when the Dodgers moved to Los Angeles, the absolute perfect age to develop a lifelong obsession with returning pro sports to one’s home borough. When the Nets deal was first announced, Markowitz was ebullient. “It corrects the great mistake of 1957, when the Brooklyn Dodgers moved to La-La Land,” he said. “This is redemption. This is Brooklyn getting its respect back.”

But Markowitz is the only one involved with this deal who seems to have an emotional attachment to the Brooklyn Dodgers. Barclays Center is not something meant to eradicate the ghosts of the past; it is a project entirely based on Brooklyn’s future. The Mets steeped Citi Field in sepia-toned childhood remembrances; Fred Wilpon was trying to re-create the Ebbets Field of his youth, to the point that some fans wondered whether that stadium was for the Mets or for the Dodgers. That is not what Barclays Center is. Barclays Center is the anti–Ebbets Field. Barclays Center has no use for your nostalgia.

The Nets organization has placed its bets on a Brooklyn that has more to do with Manhattan sky-rises and global branding than Duke Snider and Spaldeens. The venture is, in every possible way, a real-estate developer’s gamble, an attempt to get in on the ground floor of a property in an area thought to be blessed with massive growth potential. Ratner, like many a developer before him, is hoping to use the stadium to vault a city, or in this case a borough, to a higher level of Big Time … then reap the benefits in the form of basketball and concert-attendance receipts and escalating property values. The aim, that is, to both spur the creation of the new Brooklyn and profit from it.

“Barclays Center is bigger than basketball,” Brett Yormark, CEO of the Brooklyn Nets and Barclays Center, proclaims. This is the mantra you hear repeated over and over from Yormark & Co. The Nets aren’t the sole part of this deal. They might not even be the centerpiece.

Yormark is considered one of the more successful marketing executives in sports, which is particularly impressive considering how long he’s been plying his trade in East Rutherford. Yormark made his name with NASCAR as a vice-president of marketing (he’s the reason the circuit’s championship is the “Nextel Cup” rather than the “Winston Cup,” in a $750 million marketing deal that remains the biggest in U.S. sports history) and moved on to get “innovative” with the Nets in New Jersey (he devised the promotion of promising to pay fans’ tolls if they attended a game). He is originally from Springfield, New Jersey, but has the air, clothing, and cadence of a Wall Streeter, not a hair or a thread out of place, shoes so cleanly waxed they reflect a shine off the windows. I find it impossible to imagine Yormark, with his impeccable suits and matching cuff links, walking through Metrotech every day, and I tell him so. “I’m trying harder and harder to fit into the community,” he says with a grin. “This is a rapidly changing area.”

Ratner & Co. are betting New York can support two major event venues. To that end, they’ve upgraded the Nets and booked top musical acts, plus boxing, the circus, and Disney on Ice.Photo: Torsten Blackwood/AFP/Getty Images/Newscom (Dylan); Chris Pizzello/Invision/AP (Streisand); Archivo Agencia el Universal/Newscom (Bieber); Jesse D. Garrabrant/NBAE via Getty Images (Williams)

In Brooklyn, Yormark is certainly selling a lot more than just pro basketball. The Nets ownership group—sorry: “Brooklyn Sports & Entertainment,” and it’s worth noting that Yormark always, always includes the “entertainment” when discussing the Nets’ business plan—has certainly booked the place so far, signing deals to host the Coaches vs. Cancer Classic (previously at MSG), the Atlantic-10 postseason tournament (previously in Atlantic City), and three other college-hoops tourneys. It also has deals with Oscar de la Hoya’s Golden Boy Entertainment to host boxing, Live Nation concert promotions (which features Knicks owner Jim Dolan on its board of directors, by the way), and the Ringling Brothers and Barnum & Bailey Circus. Within the first six months, Barclays Center will host not just Jay-Z, Streisand, and Dylan, but Rush, Journey, the Who, Neil Young, Andrea Bocelli, Leonard Cohen, and Disney on Ice. (And of course Bieber, who has taken to wearing Brooklyn Nets gear on Jimmy Fallon.)

Essentially, Ratner and his partners are betting that New York is the one city in America that requires two major event venues. Ratner believes the whole area is underserved. “The Garden has so many events booked, whether it is the Westminister Dog Show or St. John’s games or three professional sports teams. Truthfully, they do not have a lot of available dates. I think there’s a clear demand.”

That’s why Ratner and Yormark downplay the importance of the Nets to the bottom line; if the team ends up stinking, or the Brooklyn “brand” doesn’t take off the way they’re expecting, they insist they can do just fine bringing in shows the Garden can’t book. That would be an accomplishment. The Garden, for example, derives the vast majority of its income from sports, not other events. (One thing Ratner can bank on, regardless of how the team fares, is a decent cache of cable-TV money. The Nets reportedly have a deal with the yes Network that currently pays them $20 million per season, and will increase from there, until the deal expires in 2032.)

Just the same, it would help if the Nets are good. That fate is hardly assured. Since he bought the team, almost every move Prokhorov—whose infrequent appearances at Nets games and occasional side projects of, say, running for president of Russia have done little to reassure fans that he’s anything but an absentee owner who still doesn’t quite understand how NBA salary caps and roster construction work—has made has proved wrong. He seemed to think the NBA was like Major League Baseball, and that the Nets would be the new Yankees: Whoever was willing to pay the most would win. That might work in Russia (ironically enough), but in the NBA, the superstars rule. For everything the Nets owner said the basketball team was going to be, it became the opposite. Prokhorov thought he had a chance at LeBron James or Chris Bosh or even Amar’e Stoudemire for 2011; he ended up with Travis Outlaw and Johan Petro. He went after Tyson Chandler and Nene last off-season; he ended up with Kris Humphries. The Nets haven’t finished over .500 in six seasons.

This year, the team’s most coveted off-season acquisition was Howard, at the time the Orlando Magic’s superstar center. Although Howard has told his representatives that the only team he’d sign a long-term contract with is the Nets, the team was not able to trade for him, despite arguably offering a better package to Orlando than the Lakers put forward. At the beginning of June, general manager Billy King, who admitted to me back in November that “I don’t really know this area at all, to be honest with you,” basically had three players on his roster and was in danger of opening the building with a team that was actually worse than last year’s, which was 22-44 and irrelevant all season. To King’s credit, he traded for Johnson, a solid player who’s nevertheless overpaid. That, along with the re-signing of small forward Gerald Wallace and about $75 million, persuaded All-Star and Olympic point guard Deron Williams to stick around. (Howard will still be a free agent at the end of the season, but the Nets no longer have the salary-cap space to land him.)

Even without Howard, the Nets are now at least a respectable team, and possibly playoff caliber. Still, the failure to get Howard leaves them well behind the league’s elite teams (Miami, Oklahoma City, Chicago, San Antonio) and without the kind of superstar sizzle that a team with a new home and new stadium desperately seeking relevance would find ideal. (While Williams is a terrific player, his jersey isn’t even in the top fifteen in sales; the Knicks, if you count Jeremy Lin, had three players in the top fifteen.) It took teams like the Arizona Cardinals, Los Angeles Clippers, and New Orleans Hornets years to overcome a negative first impression, and some still haven’t gotten there. The New Jersey Nets were perpetual losers; the Brooklyn Nets have to be something different, instantly.

Thus, the total rebrand. The Nets are trying to make you forget they ever were in New Jersey. Everything about the team now screams premium. The centerpiece is Jay-Z, who has been intimately involved in glitzing up the operation, from polishing the logo to redesigning the uniforms to choosing which forks are used in the private suites. The Nets are rebranding with Jay-Z class. They are more about the ambience than the food. (Though—and Ratner wants to make sure you know this—they are bringing in all sorts of Brooklyn cuisine to the concessions.)

In addition to the Vault, there’s also the Legends Lounge on the Main Concourse and the signature Barclays Center feature, the “Loft Suites.” These are private boxes like any other private box at an arena, but with fewer seats (ten), thus making it (theoretically) more affordable for smaller businesses. (By “theoretically,” I mean “$275,000 for the season.”) The loft-suite licenses also provide “use of the suite on nonevent dates.” The team says over 80 percent of its corporate boxes have been sold already. The one corporate box that’s off-limits? The “Prokhorov Suite,” sitting at the center bowl of the arena, larger than any other private box and reserved for the mercurial Russian owner. (Prokhorov told me back in November that he plans on attending a quarter of the regular-season games and “all the playoff ones.”* He also made sure that I heard him call Dolan “that little man.”) The Nets frequently note that a minimum of 2,000 seats a game will cost $15 or less, at least for the first season. Still, it’s clear that the Nets did not move to Brooklyn to be Pepsi to Jim Dolan’s Coke: They want to be Veuve Clicquot.

Ratner & Co. believe Brooklyn as a whole is already well on its way to super-premium status and will never go back. They believe Ratner has built exactly the sort of architectural showpiece and modern sports-and-entertainment megaplex that the newly gentrified Brooklynites want. They believe that Prokhorov and his staff will eventually lure someone like Howard to pack the joint to capacity for Nets games. They believe Jay-Z will persuade the biggest names in the music business to play his home arena, or fill the place himself eight times a year, if need be. They believe that the idea of Brooklyn itself—the Brooklyn brand, the actual word Brooklyn—has commercial power. As Yormark puts it: “I often tell people, ‘Shame on us if we do not leverage this. It comes for free. You do not have to pay for it, and to some degree we inherit it.’ From a marketer’s perspective, just the diversification of Brooklyn itself is a marketer’s dream.”

They’re also counting on simple logistics. “Brooklyn has the same advantage as Manhattan: urban mass transportation,” says Harvey Schiller, CEO of GlobalOptions Group and former chairman and CEO of YankeeNets, the short-lived organization that once ran the Yankees and Nets as one business and launched the yes Network. “You have a feeder system of 12 to 15 million people in the area who don’t have to drive to get there.”

But what if Ratner and his partners are wrong? What if the new titanium-coated Brooklyn is a developer’s narcissistic fantasy, and nothing more? Even in Brooklyn Heights, the borough’s most expensive neighborhood, no one fetishizes being ostentatious with one’s wealth; they’re all spending their money on the illusion of healthy food, and preschool. Jay-Z may be Brooklyn’s own, but the Loft Suites are Manhattan in every way. “From my experience, people who enjoy Brooklyn enjoy it because it’s not Manhattan,” says Tony Ponturo, CEO of Ponturo Management Group, a sports and entertainment consulting firm. ”If you feel no pride of ownership as a Brooklynite, then it’s not going to work. You have to at least make sure they’re putting something into the community that makes it feel right.”

One can argue that Brooklyn will never reach the gilded state Ratner imagines. As high as rents are going, as expensive as Brooklyn preschools are becoming, Brooklyn has a natural ceiling on it: It is never going to be Manhattan, and how could it be? It’s not in the borough’s DNA. Ratner & Co. made their bet on Brooklyn at the height of the economic boom; they’ve been working on this project since 2003. But the borough, and the world, look different now. Everything, everywhere, feels more precarious and less bulletproof. Perpetual unlimited growth seems like a long-forgotten fever dream.

Also, there is the issue of traffic. At a “public meeting” called the “Barclays Center Traffic Mitigation Plan Public Meeting,” the Nets made their parking strategy as clear as possible: Please do not drive, Nets fans. The goofy traffic consultant and civic curio Gridlock Sam, who has worked as a paid adviser on the project, flat-out said, “Don’t even think of driving to the arena. We will maximize transit and encourage sustainable transportation choices.” There will be only 541 allotted parking spots near the arena, with 612 more, amazingly, for people who are redirected off the BQE and parked in garages so far away that they will be bussed to the arena. Yes, they’ve certainly made plenty of public-transit options available—from a new LIRR and subway entrance to empty buses being available and waiting after games to extra Q and 4 trains running postgame to 400 bike-parking spaces—but still. People love cars, even in this town. The nightmare situation involves random Barclays Center patrons driving up, through, and around Park Slope and Cobble Hill all night looking for free parking.

*This article has been corrected to show that a conversation the author had with Prokhorov about his game attendance took place in November, not December.

Barclays Center, in a worst-case scenario, could end up being for Ratner what Shea Stadium was for Robert Moses (and not just because since the original Frank Gehry design was scrapped, the building is hardly architecturally distinguished). What happens if the Nets are good for a year or two and then fall off a cliff, because of salary-cap issues, because of front-office mistakes, because Prokhorov gets bored and moves on to something else? The Nets certainly weren’t good for most of their 35 years in Jersey and are far from a sure thing now. Look at the Edward Jones Dome in St. Louis, or the Palace in Detroit, or Power Balance Pavilion in Sacramento, buildings constructed with the idea of Instant Urban Status that almost never reach full capacity, albatrosses, cursed by teams that can’t contend and ownerships that constantly shift hands. At one point, those buildings and their teams were the hot new item in town, with their own slick new logos and stadiums. Then a few years passed and the teams floundered and everyone moved on to the hot next thing or, worse, moved on to nothing at all. “There’s a low tolerance for a sports fan to pay a premium for a losing team,” says Ponturo. “If the team doesn’t deliver, you can just as easily have a 60 percent full arena that’s brand-new as you can an old arena.” Ultimately, sports franchises and stadiums are toys for rich people. If they make money, great. If not, they can afford the loss and sell it to the next guy once they get bored. (Some have argued that Prokhorov has already lost interest.) And then what? What happens when the Nets flip this house?

Because if you think there was public outcry when apartments were razed and homeowners were evicted for the building of this new arena … wait until you see the uproar if Barclays Center isn’t a success. If it doesn’t revitalize Brooklyn. (And by the way, isn’t a lot of Brooklyn being revitalized without it?) If it is just another half-full arena smack in the middle of a residential area. Ratner and Prokhorov & Co. can always bail out, but we’ll all still live here.

And yet, and yet … dammit, I can’t help but be excited, regardless. It is cool that there’s a new NBA team in town, one that’s a twenty-minute walk from Brooklyn Heights, a ten-minute walk from Park Slope, a fifteen-minute subway ride from Wall Street. LeBron James will play more games here. There will be an All-Star game here; there might be an NBA Finals here. There is now a second Madison Square Garden—okay, a newer, tackier, less-iconic one—right smack in the middle of a city center (or at least what the Nets hope is a city center).

You’ll love Deron Williams; the Nets will likely win more games than they lose. Your kids will enjoy the circus, and go nuts if elephants march across the bridge. Bob Dylan’s playing just down the street from Junior’s.

Barclays Center didn’t come free. The way Ratner muscled his way into Brooklyn’s heart may never be forgotten, and we may all be a lot less excited about this in five years. Or maybe Ratner is right, and sooner or later nobody will remember how we got here. Eventually, everything new just becomes part of our daily life. All that’s certain now is that Barclays Center is real, and opening very soon now. What more can you do? Play ball.