The question came by e-mail last summer. Did I know who her husband was, and would I be interested in telling his story? Did I know who Bill Levitt was? Of course! I’d been living in his world all my life. It was the grid of identical houses we passed on the way from La Guardia to my aunt’s house in Hicksville, where I could imagine going out for milk and returning to the wrong living room and the wrong family and spending the rest of my life in a place that was not quite mine. And it was the dozens of copycat tracts that sprang up in the wake of Levitt’s innovations. I’d read lots about Levitt. He was a giant, responsible for the sameness of enormous swaths of American landscape.

But that seemed like a long time ago—could his widow really still be alive and well? I shouldn’t have been surprised. New York apartments are filled with relics and witnesses who played a role in events that happened long ago. I thought of Soong Mei-ling, Madame Chiang Kai-shek, haunting the Upper East Side decades after her husband slipped the coil—in 2003, I remember walking by the funeral home where her body lay.

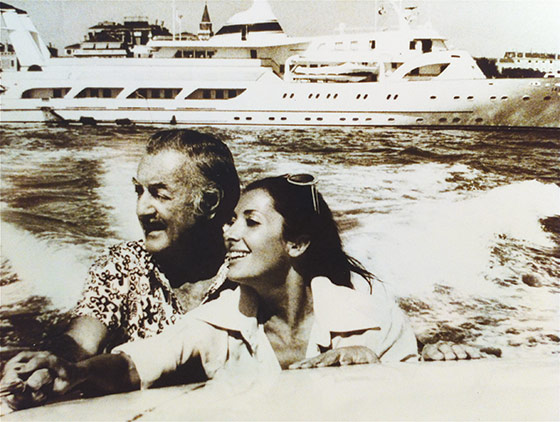

I was intrigued—Simone Levitt was a living link to a world that I’d thought was gone. I went to see her in July, then kept going back. When she was 40 years old, Simone lived in a 30-room mansion in Mill Neck, Long Island, surrounded by an extensive staff, and spent holidays on one of the largest yachts in the world, which was named for her: La Belle Simone. Now 84, she lives alone in a rented one-bedroom apartment on the East Side. On the days I visited, she had a maid to serve lunch, keeping up appearances.

One reason Simone had reached out to me was that she was, perhaps, a little lonely. But she also had a hunger to tell her husband’s story, which was glorious and tragic in equal measure, and which was her story too—she had unfinished business with the man, which I could help her with. She seemed to need a witness to this reckoning. “My husband always said he wanted to be the poorest man in the cemetery,” she told me, laughing. “Guess what? He was!”

The walls were covered with pictures of the Levitts with the most famous people in the world, movie stars, presidents. If she had not once been half of a storied power couple, you’d figure Simone had once owned a great deli.

An elegantly petite woman, Simone speaks with a lyrical French accent. She told the story of her husband in a roundabout way, each episode set off by a whisper or a sigh. She’s as old as my grandmother ever got, yet you can still see what a beautiful girl she must’ve been in the forties. “My father liked the horses,” she said. “My mother played poker. She was one of the only women in Paris allowed to play with men. But she saved our lives during the war. That’s how we ate. She played poker. Or baccarat. I would know when she won by her face. Are we gonna eat today? She died at 48. She never made it to America after the war. I came from a middle-class Jewish-Greek family. Then the war. I was in jail. I was with the orphans. I almost went to Auschwitz. I was a survivor. At 11, I was raped by a French policeman. That’s why I was afraid of men. To me, a man represented a gun.”

She lived with relatives in Brooklyn after the war and married a man she met on a ship headed back to France. He had money and took Simone to Rome, where she opened an art gallery. It became a salon for wealthy Americans abroad.

It was through her gallery that she met Levitt. Of course, she knew him by reputation: builder of Levittown, at the time one of the richest men in America. He bought so much art on so many occasions it became clear it was not just paintings he was interested in. Simone was married, and Bill was married—his second wife—so she ignored his advances at first. “I had three daughters. I’m not gonna fool around,” she explained. “But he was madly in love, he worshipped the ground I walked on, he followed me and he followed me and I succumbed. Because power. It was overwhelming. I was fascinated by his power, by his knowledge. His ugly teeth … as I fell in love with him, they began to look like pearls.”

In a manner that seems aristocratic and antique, Levitt actually asked for Simone’s hand from her husband—and he assented. Her first marriage was tired and chaste, and when I asked Simone about just how the separation was arranged, she smiled and told me her first husband saw the logic in it right away—he wouldn’t even take the money Levitt offered. “He said, ‘Simone, if I was Bill Levitt, I would have also done the same.’ ”

After he had popped the question, Bill took Simone to the Dorchester in London. “It was very proper,” she told me. “We had a big suite with two bedrooms, two bathrooms, and he greeted me with a bucket of Champagne, with caviar, set me down, gave me a little pin with a real emerald, a pussycat, then takes me by the hand to his room. So I say to myself, ‘Uh-oh, come on, you’re in for it sooner or later.’ I had already said I would marry him. I went in, he opened his closet. He said, ‘I want you to see what kind of a crazy man you’re marrying. What kind of clothes I wear.’ He was impeccable, a beautiful dresser. We open the closet, and there is a jaguar coat he had made for me. I felt like a queen. It’s like leopard, but even more rare.”

Simone stood as she talked about the coat, telling me how it wore to tatters over the years. “For sentimental reasons, I finally made a jacket [out of it],” she said, “then the jacket wore off, so I made beaver sleeves. Finally, what was left of it, I made a vest. I just had it touched up.”

Ducking out of the room, she reappeared with the tattered skin of an animal that must have run free an eon ago. It was very soft. She stroked it and I stroked it and she smiled as she stroked it. It’s one of the few items salvaged from the wreck of her old life.

“Bill was at his peak” when they got married, Simone said. “He had just sold his company for $65 million. He was in love, and there was no stopping him. Oh my God, so many stories on the boat and the crew and the captain and we would dive for fresh sea urchins and lobsters. We used to cut them when they were still alive. Don Hewitt of 60 Minutes got married on La Belle Simone. And everybody wore my clothes, Eugenia Sheppard and all these people, because it was unexpected. My captain married them. We owned the 34th floor of the Sherry-Netherland. All we did was use it to change our clothes.”

It makes sense that Bill Levitt grew up in Brooklyn. It takes a figure of the stoops and the pavement to create the dream and nightmare of suburbia. He attended P.S. 44 and Boys High, but was restless, with neither the patience nor temperament for school. “I got itchy,” he once said. “I wanted to make money. I wanted a big car and a lot of clothes.” Even then, he was a dandy, a man in worsted and silk, dressing not for the life he had but for the life he wanted. He was narrow-shouldered and more curious-looking than handsome, with sleepy eyes and the beady cast of an extra in a Frank Capra movie. He was five-eight but seemed bigger, more alive than he had any right to be.

On the boat, Bill would sit at the piano and play while Simone sang. The song on the radio, the song in his head. “Richie, he had this quality,” Simone said, closing her fingers around my wrist. “He was a wonderful man.”

In 1927, Bill went to work for his father, who practiced law in the city. “His father was a very short man called Abraham,” she told me, though she’d never met him. “He ended up taking care of the shrubberies; he used to give pennies on the street to kids.” Around the time Bill quit school, his father came into possession of land on the South Shore of Long Island. This had to do with a land deal the old man made to a developer that went bad. The property was covered with half-built houses, making it hard to sell. The only way out was ahead—finish the work, sell the development. The Levitts realized a huge profit, and the old man threw in with his boy as a homebuilder. Bill was the motor of the operation, the talker, salesman, schemer. At 22, he was president of Levitt & Sons, where he was joined by his kid brother Alfred, the artist in the family. He’d been studying art at NYU, a science-fiction freak and spare-time doodler who’d never built a thing. But it was Alfred, with his own dream of country plush, who designed the homes. He drew the first house: six rooms, two baths. An English Tudor, the McMansion of its day. It was built in 1929 and sold that August, three months before the stock market crashed. Levitt & Sons built high end in those years—only rich people could afford country life. The early developments were on the North Shore of Long Island. Bill Levitt, a salesman with antecedents in Russia, gave the developments Waspy names: The Strathmore. By 1934, Levitt & Sons had sold over 250 houses for close to $3 million—nothing compared with what they would do a few years later.

When I asked Simone how her husband had made his breakthrough, she became serious, somber, speaking of Bill as you might speak of an enigmatic historical figure, someone in a book who can be puzzled over but never fully understood. “Bill Levitt was a brilliant man,” she said again and again. “Brilliant!”

The heady moment came in the forties, she explained, because of the deprivation and scarcity of the Second World War. In other words, the same calamity that had robbed Simone of everything and put her on the street would make Levitt rich. After Pearl Harbor, if you built homes, you either had to hang it up or improvise. For Levitt, it meant the only kind of housing acceptable during the war: rental homes for officers.

So the firm signed a deal to build Navy houses in Norfolk, Virginia. In the manner of a riverboat roustabout who says he can love every woman in the course of a night, Bill agreed to finish the job in a year. It did not take long to realize it had been a stupid boast. In a boom, a developer might build 750 houses in four years; Bill promised them in one. In a fit of panic, he began to innovate. “It’s a known fact that he used Henry Ford’s method,” Simone told me. “Like [Ford] did cars, Bill did houses.”

Levitt divided home building into 27 distinct tasks, then trained 27 teams that went lot to lot, each executing a single job. In the past, house construction had been a craft, done over the course of months by a handful of men. Levitt turned it into an industry. And by the end of the war, Levitt & Sons had built close to 2,500 structures for the government.

Levitt performed his military service in the Seabees, the Navy construction division. He was stationed in Hawaii, and asked every soldier and sailor the same question: What will you do after the war?

Time and again, he got variations of a Hollywood answer: marry my girl, have a family, buy a house at the bend in the river where the cotton trees grow. But as a builder, he knew there were no houses near the bend in the river, nor on the lakeshore, nor in the forest glade. Few houses had been built during the Depression, virtually none during the war. While stationed in Oahu, as if in a flash, Levitt recognized this tremendous unmeetable need, this horde of potential consumers rushing toward a product that did not yet exist: cheap houses, bullet-size portions of the dream. It was then, as the transports filled with home-going doughboys, that he sent the telegram to his father that was overheard and repeated until it became a Long Island legend: Look for land.

The land Levitt found was in the largely empty farmland of Hempstead, Long Island, and Levitt amassed thousands of acres. His timing could not have been more perfect. Sixteen million G.I.’s were returning from the war, many needing a place to live. There were abundant hard-luck stories of couples living with parents, sleeping in back rooms, or, worse, in tents, boxcars, or the fuselages of old Army bombers. What’s more, the federal government had passed the G.I. Bill, which, among other benefits, gave ex-soldiers access to cheap loans. Perhaps most important, the banks were rolling out a product that was just as world-changing as the smartphone: the 30-year fixed mortgage. It made buying a house, which, for most Americans, had been a carrot on a stick—always chased but hardly ever caught—suddenly seem like no big deal.

Levitt broke ground in Hempstead in 1947. His method was the one he’d pioneered in Norfolk—the modern suburb, with its rows of cookie-cutter sameness, is, like so many modern institutions, a relic of the Second World War. He laid the building materials every hundred feet, the 27 teams with their 27 tasks moving across the waste. It took thirteen minutes to dig a foundation. Then came walls, the roof, a refrigerator. By 1948, the Levitts were finishing 30 houses a day. One day in 1949, Levitt wrote 1,400 contracts. He worked the desk himself, says Simone. “He was a humble man. As brilliant as he was, he would stand there, take the hundred dollars, thank the customers, and wish them good luck.”

Four years after breaking ground, the last house in the development sold—number 17,447. By then, the village had changed its name from Island Trees to Levittown. You can hold up the pictures side by side: Hempstead before William Levitt and after. In the first picture, featureless flatland punctuated by the occasional barn. In the second, a geometric swirl, everything as numbingly neat as circuits in a transistor radio. By the mid-fifties, there were 70,000 people in Levittown, and the green country of old German farmers had been turned into the Long Island of Joey Buttafuoco and my aunt Renee.

Then came the backlash. By the fifties, Levittown was being denounced for its bland sterility: little houses, little people, little dreams. Levitt is considered the father of modern suburbia, which also makes him the father of little boxes, ticky-tacky and all the same. He became associated with the worst sins of modern culture as a result. Homogeneity, intolerance. The original standard lease agreement explicitly required renters to sign a notorious clause: “THE TENANT AGREES NOT TO PERMIT THE PREMISES TO BE USED OR OCCUPIED BY ANY PERSON OTHER THAN MEMBERS OF THE CAUCASIAN RACE.” Asked to change this practice, Levitt insisted black inhabitants would scare away whites, and where would we be then? “We can solve a housing problem, or we can try to solve a racial problem,” he explained, “but we cannot combine the two.” Accused of racism, Levitt pointed out, persuasively, that when he built his first North Shore developments, he, grandson of a rabbi, excluded Jews. In other words, Levitt was not a racist; he was a businessman.

Whenever I met Simone, the text was Bill Levitt but the subtext was food—great spreads of smoked fish and bagels, pasta salad, little tuna sandwiches, the sort of tiny pickles that have confused me since I was a child. She fed me like it was the last time I would eat. Because of her childhood, she told me with a whispery sigh, because of ancient days on the streets of Paris, when she searched the gutters for cigarette butts, which she sold to buy bread. At one point, she quoted Gone With the Wind, taking on the southern lilt of Scarlett O’Hara, saying, “I tell you, Richie, I am like that girl at the end of that movie: ‘I will never be hungry again!’ ”

When Simone met Bill, he was at the peak moment of his life, having sold his company and amassed one of the world’s great fortunes. He frequented her gallery, buying up whatever she got in, as if throwing money from the back of a train. In him, Simone saw not merely a wonderful man but safety, freedom, and a final hedge against oblivion. In fact, Levitt was already an hour past prime, having made his last deal and achieved his last success. Simone was signing on for the third act, pulling up a chair in time to watch the sun go down. Their love affair began a moment before his tragic decline.

Telling me the story of her love and its aftermath, Simone was fully an actress. She wore scarves when we met, printed garments that covered her head and showed her face, and deployed a whole arsenal of gesture and intonation, younger incarnations of which were the ones that had captivated Levitt. When Simone married Bill, she took on his money and took his homes but most important she took his story, which, when they met, promised to be nothing but a fairy tale from start to finish.

By the end of the fifties, he was among the most successful men in the country. Having gone on to build developments in Bucks County, Pennsylvania, and Bowie, Maryland, he was also among the richest. For a moment, he seemed to stand for the best of capitalism. Having helped so many people live the American Dream, Levitt seemed, on the surface, to be living his own. But in the sixties, the trajectory of his life began to change. It started with his father, Abraham. He’d grown old by the sixties, slow-footed, watery-eyed. At Levittown, he’d been passionate about the landscaping. He’s considered a pioneer of the modern lawn, a reason rolling weedless perfection became the green screen of suburbia. He died in 1962. After that, the family came apart. Bill and Alfred’s mother died. The brothers became estranged. Alfred quit the firm.

And with the family out of the company, Levitt decided to get out, too. In 1968, he sold the firm to ITT—the International Telephone & Telegraph Company, which was the glamour company of its era. The price was $92 million, $62 million of which went to Bill, who was paid in stock.

Simone was Bill Levitt’s prize, what he reached for when he finally decided it was time to cash out. There was the yacht and the house, and then there was the ingénue. For ten or twelve years, the Levitts lived as well as anyone ever has. “He came from Brooklyn, a poor little boy, and got himself an empire,” Simone told me. “He built the most beautiful home, had the pride of giving, fell in love, gave me the biggest, most beautiful yacht in the world. He had a Rolls-Royce, a chauffeur. He bought me a 1929 Ford for my birthday. He celebrated my anniversary every month for ten years. I had to beg him to stop.”

What about the estate in Mill Neck?

“It was impressive,” said Simone. “Off the bay. A beautiful mansion. Seventy-five acres. We had our own superintendent, our own nursery, vegetables, chickens, eggs. When you came to visit, we would fill your car with gasoline, put lettuce and flowers in your trunk.”

Simone loves literature, has read everything. Now and then, as I lingered in her doorway, she pressed a book into my hands, a text meant to elucidate her own story. (Upstairs, at this moment, Simone’s copy of The Paris Wife sits, waiting to be read.) She knew the sad fate of Anna Karenina and Madame Bovary. She knew about third acts and second chances and poignant last-minute turns of plot. For this reason, she was not ruinously surprised to discover that things were not quite as they seemed with Bill. In fact, as Simone was turning like the bride atop the wedding cake, the ITT stock was losing value—some 90 percent in the four years after the sale. The corporation was failing, taking Levitt’s fortune with it.

But it took Bill too long to notice. Perhaps this was the fatal weakness of the Brooklyn mind. No matter how smart, the outer-borough boys always put too much faith in the storied concerns of capitalist America. “[He’d been] mesmerized [by ITT],” Simone told me. “He was very impressed by these people, and they could do no wrong. And he put all of his eggs in one basket, which was a huge mistake.” Worse still: Levitt, who, as part of the sale, agreed not to build houses in the United States for ten years, had borrowed millions against the stock to finance overseas projects. As the stock lost value, he had to make up the difference to the banks. By the mid-seventies, he was in the sort of trouble only a gold strike can fix. Which is why he tried, rather insanely, to build houses first in Nigeria, then Iran. Each plan, sold with great fanfare, ran into reality: ayatollah, oil crisis. This man, who rode the historical winds to fame and fortune, was plunged to Earth by those same forces. Pilots call it a wind shear: One minute, you’re soaring; the next, they’re picking up your remains with tweezers.

The decisive blow came in Venezuela, where Levitt lost millions when a change in oil prices made the government cut back on mortgage guarantees. “It was the day before Thanksgiving,” Simone told me. “I had 22 people over for dinner. I hear [Bill] on the phone asking them to wait one more day, please, we’re having company. In the car [later], he said, ‘Honey, they’re going to come to appraise the paintings.’ ”

Levitt tried to shelter Simone as his business fell apart, but desperate men have a way of letting the world in. One night, in Las Vegas, where the Levitts were attending an Alan King charity ball, Bill told Simone to wear her best jewels—he’d given her millions in diamonds and rubies over the years. She assumed he wanted to show her off.

On the way back to the room, Bill asked Simone to share a nightcap. It was a strange drink she later suspected was a Mickey Finn. And then it was late and everything was spinning. He told her to forget about putting the jewels in the safe at the registration desk as she’d done previously. “Before we went up, Bill said, ‘Let’s not go through the casino because there’s gambling and people are drunk,’ ” Simone told me. “ ‘There’s a sign that said BOLT YOUR DOORS. Let’s bolt our doors.’

“In the morning, I’m in the bathroom brushing my teeth and I say, ‘Honey, don’t forget the jewelry.’ And he said, ‘What jewelry?’ He told me not to put it in the safe! I said I took it off and put it right there. There was no jewelry.”

At the time, Simone believed the diamonds and rubies that had disappeared from her bedside had been stolen by a hotel employee or other intruder as they slept. But suddenly, as she spoke to me, a doubt appeared, a further mystery. “Something was put in my drink,” she said. “Whether something was put in Bill’s … until this second, I assumed he had it too! Because the minute I hit the pillow … but in the morning, come to think of it, he said ‘your jewelry’ as if he wasn’t surprised. All of a sudden, this is hitting me. Why wasn’t he surprised? Why wasn’t he upset for me?” She’ll never know.

By the late eighties, Levitt was out of everything: money, patience, ideas. When he could not pay his debts, he sold the yacht and the house in Mill Neck. Simone sighed as she catalogued each loss, eyes sparkling. She told me that her early travails “taught me how to survive. I don’t get excited; I don’t feel sorry. My brain goes immediately to ‘What am I going to do? How do I solve it?’ So when Christie’s took everything, I have no self-pity. I sold everything that was left to my neighbors. I sold everything and brought the checks to Bill to make him happy.”

Near the end, Levitt pitched two new developments in Florida meant as a retirement community for graying denizens of Levittown. He took money but never finished building, using the cash to pay his debts. When caught dipping into a charitable foundation set up years before, he was prosecuted by the New York attorney general’s office. He was ordered to pay back $11 million—money he did not have. In short, in addition to financial ruin, he suffered humiliation.

“You know what that’s like, when you really get a lot of luck and then it starts going wrong,” Simone told me. “If he’d had time, it would have gone back up, but he didn’t have time. So Venezuela went to pieces, and before you knew it, that was it. That’s when he began … not to give up, but he had no choice. There were terrible articles, and he would say, ‘Ah, Simone, it’s yellow journalism. You can’t believe what you read. Do you trust me?’ And finally, by the time my friend [told me the truth], they closed up the electricity, the phones, [and] he was under Valium.”

It was only at the end, when every step came to seem like a step down, that Simone began to look out for herself. “Before we sold the boat, he bought me a 27-carat diamond that was unbelievably beautiful. And that ring, I will never forget it. By that time, I knew we were in bad trouble. Sitting in the kitchen in a condominium—after this mansion, we rented a condominium—he says, ‘Honey, give me that ring, I’ll make it up eight times for you.’ And I remember saying, ‘Darling, I’ve given you back everything you’ve ever given me. But this ring, I’d rather swallow it.’ After he died, I sold it—this is how I’ve made my life. I sold that diamond at Sotheby’s, and I demanded a million, but it only sold for $800,000. That’s how I made my life again.”

In his final years, when he was wracked and busted, nothing but a name, a legend and a dollar or two, a reporter took Levitt out to Levittown, a ruin coasting beneath the elms. The town had changed. People had added floors and wings to their ranches and Cape Cods, lean-tos, overhangs, dormers, garages. They’d busted out of their boxes. Sparkle and fancy flourished, demonstrating the quality of soul that strives for individual expression. Perhaps Levitt just wanted to see it again, to remind himself it’s real, it’s happened, I did it, it’s here. He was like God drifting through his garden in the cool of the evening, but a suburban God, the only God we deserve, an ailing, faded deity who has lost everything.

William Levitt died on January 28, 1994, in North Shore University Hospital in Manhasset, Long Island. The official cause was kidney disease. He was 86 years old and unable to pay for his care.

Simone turned out stronger than Bill. Eventually, after one too many failures, he lay lifeless at the bottom of his string. He ended in a haze. But Simone always comes back, jaguar coat and all. She is poor, she is rich, then poor again, but that was far from the end. I realized that, as much as the story she’d told me was about a tragic man, it was also one of triumph—her triumph. Because she’d kept going, living richly, making things. For years, she was a friend and muse to Janet Brown, a well-known Long Island fashion designer, with whom she’d lived for a decade. Now Brown was gone too—but that opened the door for the next thing. And anyway, her story, the one she’d just told me, was more valuable than any jewel. No husband could take it away.

When I asked about her state of mind—what does that kind of loss of wealth and status feel like?—she smiled the way Ruth Madoff might smile if she became a Buddhist. “We had a life that was unimaginable,” she told me. “But I’m happy with today. Look, I told my daughter—she bought a new apartment—‘Nicole, don’t be cynical. You’re forgetting to enjoy today. Don’t say you can’t wait for it to be finished. Don’t do that. Squeeze everything out of the moment. Don’t look for tomorrow.’ I don’t look back. If I do, I never regret. I appreciate. I believe that nothing is forever. The painting on this wall, in another five years maybe it’ll be on someone else’s wall. My rings and jewelry, the shirt I have on, it will be on somebody else. Nothing and nobody lasts forever. Everything changes hands.”