After I was expelled from boarding school, kicked out one month shy of graduation for boozing and for a condition that might best be labeled “extreme chronic malingering,†I was sent to an old-fashioned psychiatrist on the Upper East Side. This was the early eighties, or halfway between the respective heydays of Holden Caulfield and Prozac. Though the idea of the adolescent hallowed by his suffering had stiffened into a cliché, it wasn’t yet the fashion to put a problem child on meds. I still remember walking into the churchly lit office, with its framed poster of William Jennings Bryan’s “Cross of Gold†speech. To that point, my notion of therapy was informed by little more than Judd Hirsch in Ordinary People.

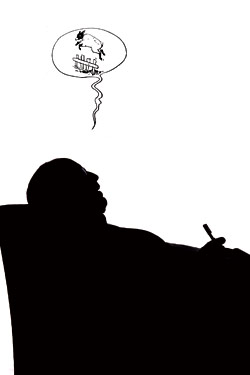

The doctor was a middle-aged man with a low-slung, do-si-do voice, cowled eyelids, and a silver Cross pen poised above a yellow legal pad. I regarded him as little more than an agent of my parents, and so, aside from a twice-weekly deconstruction of Hubie Brown’s Knicks, refused to engage him. What followed was an old-fashioned Freudian face-off: I sat in a stone-cold silence that he declined to break, a magisterial reticence no doubt meant to open a crawlway to my unconscious mind. We were all but motionless in an all-but-airless room, repaying each other’s muteness in kind. It’s no wonder what eventually happened. The doctor fell asleep.

His eyelids would droop, his head loosen, his chin loll slightly forward, and then—a telltale jerk back into some semblance of attentiveness.

Thirty years and four shrinks later, I’ve come to recognize these signs. I have consulted four therapists in my life, and all four have fallen asleep on me. The ritual—forms, waiting rooms, Kleenex—starts up again, only each time with my own special twist: I pay someone to explore my unconscious mind and instead they sink into theirs. So consistently did I lose wakeful contact with my shrinks that I began to suspect—honest to God—that feigning sleep was a technique for provoking patients to confront their fears of abandonment. “Once in a 40-year career,†said a friend’s shrink, an ancient and cheerful Jungian, when I asked him if he’d ever drifted off while on the clock—making me, I suppose, the Ted Williams of narcissistic monotony.

A little while ago, at a dinner party, I met a prominent analyst, a Kleinian. He is the first therapist I’ve known socially, and I confided in him. “I’d like to go back into therapy, but all four therapists I’ve seen in my life have fallen asleep.†He didn’t laugh. Nor did he ask me how I felt. Instead he took it in, turned it over in his mind, then said, very carefully, “Well, the common denominator here is you.â€

The comment lingered, as any stab wound to the chest would. Then, a week later, he e-mailed me a PDF. “In the past I noted a tendency in myself to become drowsy with two patients,†wrote the analyst Edward S. Dean in a now-infamous 1957 paper. “At times this drowsiness became so strong that I desired more than all else that the hour end, that I be rid of the patient and could take a brief nap. I was surprised to observe that as soon as the patient left, I became instantly fresh and alert.â€

The sleeping analyst is not common, but it is not unheard of, and Dean’s paper has been cited in most treatments of the subject since. And no wonder: He taught the analyst to interpret his own sleepiness not as malpractice, or even an embarrassing if inevitable bêtise, but as evidence of the patient’s “tenacious and insuperable resistances.†Explicitly following Dean’s lead, successive analysts have generated a composite portrait of the sleep-inducing patient as a kind of negatively charged superhero. He can be so powerfully dissociative, “the analyst feels depleted or half-alive, and thus disorientated and out of touch with the basis of what is most alive, or would be most alive at that time if the patient were truly there.†Typically he suffers from “passive-obsessional and narcissistic character disorders, [using] isolation, inactive rumination, concealment and displacement of affects to control and dull into passivity the patient himself as well as others.â€

Therapy is unlike any other social situation. It is a highly ritualized encounter designed to take the immense dead weight of the past and budge it, inch by galling inch, in the direction of change. But therapy is also like any social situation. It is a kind of performance in which we seek to convince, to charm, and, if necessary, to put on the cap and bells of our suffering, to sustain the attention of another. Over the years, my feelings about therapy hardened. But the Kleinian, and his forwarded paper, have made me reconsider. I’ve now gone four for four. Are my own powers of resistance so enormous that the composite portrait of me, as an isolated, narcissistic evader, is unavoidable? Can an abandonment of minimal professional duty—to stay heedful of what a patient says, no matter how stonewalling—really be answered with an evasion, a theory, a cliché? Who are the bullshit artists here? Them or me?

I went back to see them to try to find out.

Returning to an old therapist is like finding an old mirror in the attic. You dust it off, smile at the frame’s filigree, then recoil in horror to discover its reflection still retains your childhood face. My maiden therapist, dating back to the Hubie Brown years, refused to return my phone calls. As one of the first American analysts to plead guilty to insider trading (a patient of his was the wife of a noted financier), he was no doubt unnerved by the sound of a journalist on his answering machine. That his voice, meanwhile—the Eeyore-like cadence—could sit so unceremoniously on an outgoing message, and still be so provocative to the recesses of my memory, gave me an uncomfortable foretaste of the experience to come.

Therapist No. 2’s office is still tucked in the same small complex on the fringes of a college town, where suburbia melts into farm country. NPR murmured on a dual-cassette boom box, which sat on the floor next to an empty Poland Spring cooler, which was tucked beneath a framed Georgia O’Keeffe poster—everything just as I’d left it twenty years earlier. During my therapy, I used to play the manipulative child, confronting my therapist with the latest anti-Freud aperçu from one of my comp-lit professors, a veteran Freud-basher of some renown. She would sigh and say, “Your professor needs to update his ideas about therapy. We have.â€

Obscurely compelled, I suppose, to repeat past behavior, I had stopped by my old professor’s office en route. “Freud happened to be a physician, the same way Schopenhauer happened to be an idealist philosopher,†he said, tilting back in his beat-up brown leather chair. “His work is a brilliant interpretation of the self and the world, but it fails as a therapy. But he was a physician—and so Freud believed he had to cure people.†Not Freud’s problem alone, I thought, driving at a homicidal speed, trying to make my appointment on time. Would I bother recounting my previous night’s dream to a stranger if I didn’t think it would make me better? Admittedly, “cured†is out of the question, I thought, seated in my old therapist’s waiting room. So if not cured, what? Go ahead, say it. Say the word “journey.†I hate the word “journey.â€

“Hello, Stephen.†She stands in the doorway, a tiny woman in muted lamb’s wool, a look of friendly anticipation on her face. I cannot quite grasp how satisfying it is to see her. She is older, of course, but it comes back to me in an instant—her patience, her measured but palpable concern, her frequent if gentle skepticism, her wonder while staring at the towering ramparts of my neurosis. Seated, she asks me why I’ve come. “I’m on a kind of … journey,†I say, wishing at that moment a grand piano would, taking mercy on us both, fall through the ceiling. But soon enough our conversation becomes free-flowing and frank. As we talk—I tell her about my marriage, my children—I think, This is like therapy, and yet not like therapy. It’s like Moses Malone and Jabbar playing a charity pickup game. The moves are creaky, yet strangely familiar.

When I first met this therapist, I was a nihilist bristling with a hostility I mistook for confidence and a nervous laugh that sounded like a bagful of frenzied grackles. A tree with pasted-on leaves, as the poet Anne Sexton once wrote about a friend, though she added: “you’ll root / and the real green thing will come.†I feel like a different being now. And yet she still insists I suppress a deep and mostly unconscious rage against my mother. I disagree with this—resistance!—and we go back and forth, but without any of the old aggressive friction. Then I ask her: Do you remember falling asleep during our sessions? And the conversation goes dead. Her chin retracts; her eyes lose focus.

Nothing more, nothing less, therapy is the art of teaching someone to overhear himself. This woman taught me to overhear myself and begin to live beyond the service of my infantile needs. She dared me, by asking simple but, in retrospect, quite cunning questions, to think of my would-be existential jailers—my parents, my teachers, my friends, my enemies—as my fellow inmates. But now she answers the question of her sleep haltingly, to put it mildly. “You were so … heavily defended. When a patient is defending against me … my insights … can be anesthetizing … I’m being excluded … repelled … I can get sleepy.†The Dean defense! The sky-hook of snoozing analysts! I can’t help laughing, and I can’t help noticing, for the first time in years, how my laugh still sounds like a bagful of imprisoned birds.

Browsing through the literature on sleepy analysts, I was struck by how united the analytic community is in interpreting its own sleep. Variations of the Dean defense abound. And yet analysts stand utterly divided on what the sleepy patient might signify. Is it primary narcissism, hallucinatory regression, a desire to retreat into a womblike state? Freud thought each of these at different times; he even thought it could be a repetition of our infantile withdrawal from the pain of our own childbirth. Or maybe it’s a hostile urethral (no joke) reaction to the analyst? Or maybe the desire to be united with the good mother, or a regression to the infant’s inability to accept the nursing breast? The disdain its critics feel for psychoanalysis is not hard to fathom. You pay a handsome sum to sit across from a real, living, breathing human being who, when confronted with your agony, presents you with a toneless expression and the gelid “And how do you feel about that?†Meanwhile, in his notebook, he jots: “Patient exhibits hostile urethra …â€

Back in New Haven, passing the hulking Gothic enclosures designed to protect Yale students from, seemingly, everything, I am in a morbid way. It’s true, grad school bestows freedom upon its attendees to luxuriate in the best of what’s been thought and said (and in beer). But over time, you’re in danger of becoming a lifer—part veal calf, part hothouse flower. At Yale, I had a swank fellowship, met literary critics I’d worshipped since childhood, read English Romantic poetry, studied Latin and Greek, and I went to the gym ceaselessly. The weightlifting could stand in for the entire experience. I piled higher and higher weights on top of my meager frame, lying on a bench, beet-faced, pushing them off me, and as I did, I only seemed to get weaker. In grad school, I read more and more books, and as I did, I only seemed to get stupider. In therapy, I added more and more sessions, and as I did, I only seemed to get sicker.

My therapist here was a Freudian who pushed me to take more sessions, to become a fully subscribed, five-day-a-week head case. I remember him only indistinctly, as a tweedy-shabby figure, a lifetime of neurotic confession—oh, city of thwarted glory!—clinging to him, the way a lifetime of johns clings to a prostitute. Does it come across how much I looked forward to this reunion? And yet the man who greets me at the door of his office is … Judd Hirsch. Circa Ordinary People. Seriously. An evidently humane and friendly middle-aged Jewish man in chinos and a button-up oxford. He is genuinely puzzled when I tell him how bitterly I recall our working relationship. “Really?†he says. “You speak of transference. Well, there is countertransference. And I remember you fondly.â€

Asked about falling asleep during our sessions, he replies, “Oh, after lunch, glucose in the bloodstream, insulin, tryptophan …†I press him, and he says, “Well, why did the English take their tea in the afternoon?†Pressed, he says the question of his sleep “clearly distressed you.†To a man with a hammer, Mark Twain wrote, everything looks like a nail. Sitting across from my old doctor, in the late afternoon, in an old New England mansion, with its soughing radiators and pockets of gray light, it’s hard not to think of psychoanalysis not only as a dying art but as a ball-peen to the right eye.

Soon after moving from New Haven to New York City, my wife and I made fast friends with a woman who was French, in the film business, and beautiful. If someone were bullshitting her, I reasoned, it would have to be exquisite bullshit. So when my wife learned that she was pregnant with what would become our first daughter, and I flew into a panic, I called our new acquaintance for her shrink’s phone number. She referred me to an elderly man, deep in his seventies, with an M.S.W. and a shingle in the West Village. I remember carefully scanning his face for evidence of stupor, even as I labored to stay vividly and emotionally present. He fell into the deepest sleep, snoring like a bass clarinet. I was left to decide whether to wake a kindly old man or tiptoe silently from his office.

The morning I returned to him, for this latest and last of my therapeutic journeys, I stumbled upon a poem by John Betjeman called “Loneliness.†(“What misery will this year bring / Now spring is in the air at last? … But church-bells open on the blast / Our loneliness, so long and vast.â€) A grim meditation on death, but what a relief, I thought, that someone once called it loneliness, and not depression—to be alleviated by intimacy, not medicine or pity. I had forgotten how on his bookshelves, aside from the usual shrinky tomes, sat volumes by Berryman, Lowell, and Sexton. He is thinner now, less robust. I ask him about falling asleep, and he says, cheerfully, “I have no memory of that whatsoever.†This is surprising, considering he passed out cold, I exited quietly, and we later spoke about it intensively. “What did I say?†he asks. That I had been locking him out with emotionally evasive speech. “What did you say?†he asks. That that was a bullshit answer. He pauses. He smiles. “Good for you.â€

When I tell him why I’ve come, he thinks for a moment. Then he adds, “This event that you speak of. It happened to me. Twice.â€

“You’re joking. Now I feel more like a journalist than a patient.â€

“I prefer ‘analysand.’ â€

“Okay, then, analysand. Though that sounds so Freudian.â€

“I hold nothing against Freud.â€

“Really? Nothing?â€

“No. He wasn’t a very good analyst, but he was a remarkable thinker.â€

“He fell asleep on his patients. Excuse me, analysands. On Helene … â€

“Deutsch?â€

“Thank you, yes, Helene Deutsch.â€

“Was he facing her? Or behind?†he asks. Oddly suggestive, but it allows me to play the A student. “Behind. She knew he had fallen asleep because she saw his cigar drop to the carpet.â€

He laughs, a light, high, and dry nicker. “Ah, that is wonderful.â€

“So, about falling asleep …â€

He smiles.

“Would you like to lie on the couch, and we can talk about it?â€

“Seriously?â€

“Yes!â€

“In order to talk about your sleeping analysts, I have to lie on the couch?â€

“I’m not going to blackmail you,†he says, but very coyly. I had thought the back of my head would never touch the miserable doily again. Yet here I am, staring at a Friedrich wall unit.

“One was my supervising analyst; one was my training analyst.†Having gotten me where he wants me, he digs right in. “Here is what happened: With my supervising analyst, I was talking along, and I was suddenly aware she was sleeping. And then she woke up, and this is what she said. She said, ‘What have I missed?’ My training analyst, meanwhile, fell asleep with some frequency. I’d just talk louder, and he’d wake up. I’d say, ‘Did you have a nice nap?’ And he would say, ‘Yes, thank you.’ †How very tidy.

“Did you feel like there was something about what you were saying, or how you said it, that made them fall asleep?†I ask. “Possibly. How can you know those things for sure? It didn’t really bother me. It was part of the relationship, of getting to know each other over the years. He was the founder of modern psychoanalysis. This was a very honest person.â€

I did what anyone would have done next: I ran home to Google “modern psychoanalysis founder.†I learned that in the fifties, a man named Hyman Spotnitz began shifting American analysis away from rigidly formulaic diagnoses and toward a more supple understanding of the individual transference. Against the authority of the analyst as a bearer of reality, to which the analysand need be reconciled, Spotnitz promoted the idea of two people, alone in a room, talking. (He expanded that by promoting “group therapy†in the sixties.) Spotnitz believed that neurosis, along with most forms of mental illness, originate in the pre-Oedipal, preverbal, even possibly prenatal stage of life. He believed in the transference, and also in the countertransference—that by joining in with and encouraging the patient’s fantasy of the analyst, the two people, alone in a room talking, could come to understand the shape and nature of the patient’s neurosis.

Hyman Spotnitz founded modern psychoanalysis. He was my analyst’s training analyst, and he fell asleep with some frequency. So this sympathy, this lack of judgment; it is classically Spotnitzian! It is all part of the method! Like the bus driver handing me a voucher, he’s encouraging me to transfer! Could it be that even the stories of his analysts falling asleep are only technique? This sympathy, only one more cunning induction to join? “It must have been hurtful,†my analyst continued during our meeting. “I was the fourth one. I don’t know, now that we’re talking about it, that it had anything to do with your conscious. I think it may have been with your unconscious. Analysts are trained to listen to the unconscious. In the analytic situation, we get back to preverbal times. One often can find words for something that didn’t have words. They often say, ‘Tell me what you don’t know.’ â€

The Friedrich air conditioner, an old warhorse, juddered painfully. If nothing else, I have mastered this repetition: of lying in an office, pondering psychoanalysis. I’ll tell you what I don’t know: I still don’t know whether I am being helped or fleeced like a little baby lamb. “We’re always working in this room,†he murmured, as the final minutes drained from the hour. “Both your unconscious and conscious, and my unconscious and conscious, are together in this room with us. This is a remarkable room, in one way. A lot goes on in here that wouldn’t go on anywhere else.â€

Thirty years and four shrinks later, and what have I learned? My personality seems to come with two presets: stentorian bore and class cutup, neither of which exactly enchants the mental-health professional. “Character isn’t fate,†I say to my friend Adam, now living in England, over the phone. “Isn’t this the very American lie that sends us crawling back to the shrinks?â€

“I suppose.â€

“To see how the little, invisible filaments that weave together the individuals in a family into a single unit—how over time they turn to iron ore and become your character? I mean, to somehow exit the labyrinth of the group mind that conceived you? To move toward enlightenment and a hair further toward mitigated misery …â€

“We’re on metaphor four, here, Steve.â€

“To penetrate the self and transcend it …â€

“Steve, hang on a sec. Zzzzzzzzz.â€

By this time, the jig is up; you see what I’m about. Admit it: Like my friend Adam, you’re getting sleepy … very, very sleepy. The problem is, of course, just as the problem is in my therapy, between the yuks and pseudo-insight, I’ve revealed nothing of substance. If I’m entitled to keep the Gothic particulars of my self-dispossession quiet, well, then, you’re entitled to the Dean defense. But to break the spell, I will tell you a story:

In 1963, a young and very unmarried girl in Poughkeepsie discovered, to her mounting terror, that she was pregnant. Her father was an IBM executive—this was when IBM executives were confined by sumptuary bylaw to wear white shirts and blue suits—and her mother was from the proper South. The household was run on the fifties model: The father was an authoritarian, everyone else toed the straight and narrow, and God forbid the neighbors found out. The young woman dropped out of college, and conveniently disappeared, to the Inwood House for wayward girls in lower Manhattan. The Inwood was then located in a large brownstone and run like a dormitory, with about twenty girls in residence at a time. There was a nurse and a Friday clinic, and, in offices across the street, a weekly group-therapy session. In November, the president was shot, and West 15th Street filled with pregnant girls, listening to the radio and smoking.

In January, she gave birth to a boy, and with a social worker holding her hand, she cabbed it up the FDR, to an adoption agency on the Upper East Side. On his 14th birthday, she wrote a letter to her son via Ann Landers—“Going into your teen years, I wanted you to know you had been loved, and are lovedâ€â€”that Ann Landers did not print. The young woman was my mother, the baby boy was me. I first heard this story in my late thirties, sitting with her in a small picnic area overlooking the Hudson River. That is my preverbal, prenatal story; my ancient prehistory. After I heard it for the first time, I boarded a train in Westchester and returned to the city. And then something peculiar happened. I fell asleep—not just asleep, but into the deepest sleep of my life. When I woke up, the train was empty, sitting idle in Grand Central. The platform was empty, too. I had slept through the thronging of passengers exiting a crowded New York commuter train and then slept for an additional half-hour in the deserted car. No conductor was in sight; no one; not a soul.

I have never felt so cleansed by sleep; I’ve also never felt so alone. What could it mean? I haven’t the slightest idea. But I have decided, for now, to leave that stone lying at the base of its Sisyphean incline. Instead of gearing up again—forms, waiting rooms, Kleenex—I called my biological mother and told her about my four therapists and how they had fallen asleep on me. She laughed and laughed and laughed, then said, “Did you ever think it means maybe you don’t need therapy?â€