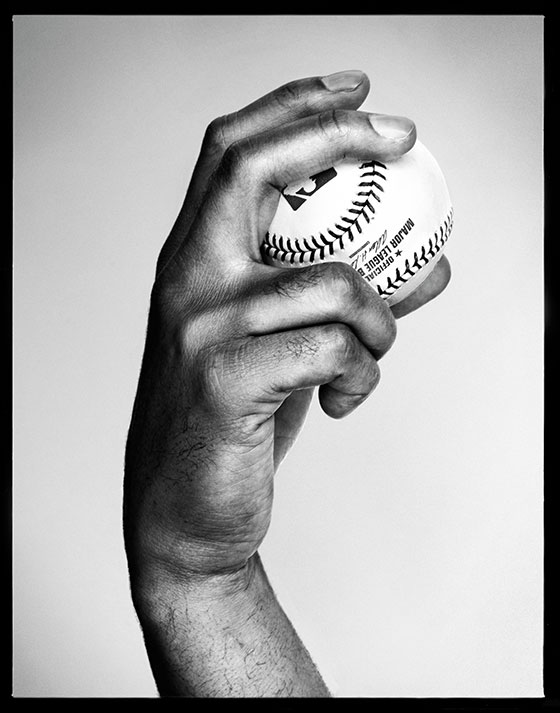

As anyone who follows baseball knows, Mariano Rivera has built his career on one pitch. A cut fastball, or “cutter,” it travels at 90 or 92 miles an hour, and then, a few feet before it reaches home plate, it moves half a foot off course, a trick of physics that looks like telekinesis. Rivera’s cutter is virtually unhittable, by consensus and by the numbers, but the wasteland of broken bats that litter the plate when he is on the mound is all the proof anyone needs. A Rivera inning has thus been compared to a horror movie: The excitement is sharpened, not dulled, by the fact that everyone—the players, the ticket holders, and Rivera himself—knows exactly what’s coming. Consistency and predictability may be the dullest of virtues, but in Rivera, the anchor reliever for a nearly two-decade Yankees dynasty who will retire at the end of this season at 43, consistency itself is manifest as a superpower.

Three months into his final season, Rivera’s hagiography is already being written. He has, for seventeen years, been the Yankees’ closer, the specialist who arrives in the ninth inning to protect a tight lead, and at this he is better than anyone else who has ever played the game. With 21 saves so far this season, he is pitching as well as he ever has, at an age when other ballplayers have long since withered, and after a long winter recovering from surgery for a torn ACL, an injury that cut short his 2012 season and has ruined many players much younger than he. His teammates speak of him as a giant, and they express gratitude for the privilege of merely being able to walk in the clubhouse where he has walked; atop the Yankees’ Olympus, populated by Ruth, DiMaggio, Gehrig, and Mantle, there’s already a name tag on Rivera’s throne. Sportswriters see him as a mystery, for while other closers have had brilliant seasons, even stretches of three or four, no one else has ever been as good for as long, not nearly. In trying to explain his unprecedented and ruthless two decades of dominance, they’ll cite Rivera’s natural athleticism and the simplicity of his mechanics and they’ll mention the advantages of having been tutored and coddled during his long career by the rich, paternalistic Yankees organization. Rivera acknowledges these things with gratitude—all true, he says. But in his view, his greatness has no earthly source.

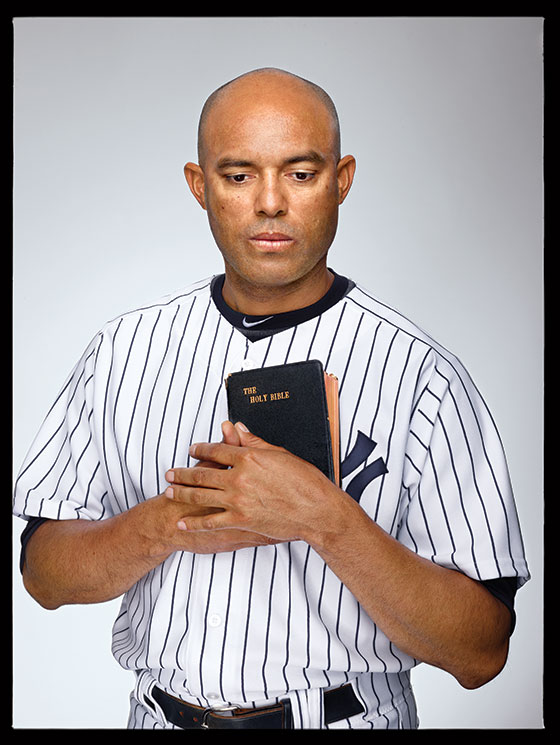

“Everything I have and everything I became is because of the strength of the Lord, and through him I have accomplished everything,” he tells me as we sit shoulder to shoulder in the Yankees dugout on a temperate, breezy spring day last month. “Not because of my strength. Only by his love, his mercy, and his strength.” It is the first of several conversations about God I have with Rivera, over several weeks, and in each meeting I find myself struck by how eager he is to put baseball aside and speak openly, and at length, about his faith. Even as Rivera denies that his talent belongs to him, I steal a look at his magic right arm. “You don’t own your gifts like a pair of jeans,” he says.

By that reasoning, I venture, you might say that even the cutter doesn’t belong to you.

“It doesn’t,” he answers, nodding emphatically. “It doesn’t. He could give it to anyone he wants, but you know what? He put it in me. He put it in me, for me to use it. To bring glory, not to Mariano Rivera, but to the Lord.”

Sportswriters often discount athletes’ religiosity as a sideshow, and the secular viewers of cable TV may prefer the bloodless scrutiny of slo-mo video than to give credit to divine causes, but the full story of Rivera’s career is unmistakably a story about faith. On the mound, Rivera is implacable, a warrior with the Buddha’s face. But talking about faith with Rivera is like opening a bottle; years of feeling come out. He speaks less like a theologian than like an enthusiastic believer, channeling all his considerable charisma, curiosity, and preternatural seriousness into the conveyance of passion. His is not a questioning faith but a conviction, invulnerable to attacks from skeptics and doubters, and so his answers to existentially vexing questions can sound to some uncomfortably neat. But Rivera isn’t worried about rationalist complaints because it is in certitude that he finds his strength.

Baseball is full of nutters and head cases, and closers are among the nuttiest of them all—the game’s wildest men and drama queens, the gloaters and the long-haired fist pumpers. Closers employ all kinds of mental tricks to shut down the voices in their heads: They pretend they’re back in the minors where nothing really counts, or they visualize blondes behind home plate. But Rivera doesn’t need tricks. His eye is on a bigger prize, which is to say Heaven, and that has a way of placing more quotidian anxieties about stats, standings, and contract deals into perspective. “At the end!” he says with so much suppressed excitement I think he might explode. “That’s where I want to become a giant. That’s where it counts. It doesn’t matter now.” The certain knowledge that God is at his side, even on the mound, gives Rivera a kind of mental equilibrium that most players (and most people) can only yearn for, a profound mixture of fatalism and personal responsibility best captured by the AA mantra, the “Serenity Prayer”: “God grant me the serenity to accept the things I cannot change, courage to change the things I can, and wisdom to know the difference.” Rivera likes to win—“everybody does,” he says—and he believes that giving his life to Christ puts him on the right team. “As long as you cross the [finish] line with the Lord, you’re a winner.”

His faith does not relieve the pitcher of his responsibilities; he is no puppet, and God isn’t calling the pitches, Rivera tells me, laughing at the suggestion. The fact that his gifts come from God increases his obligation to honor them with the hard work and discipline for which he is famous, he says. When Rivera botches a save, it’s his failure—but it’s also part of God’s mysterious plan. “You have to do your part,” he says. “And he will do everything else. You have to be there. Sometimes it doesn’t go your way, but it doesn’t mean that he’s not in control. Sometimes it doesn’t go my way. I have lost the World Series. I have lost games in the regular season. I have lost games in the playoffs.”

It’s a two-tiered system, in which God controls ultimate outcomes from Heaven while down in the stadium Rivera takes perfect aim to win. Too many people claim a religious faith only when it’s convenient, Rivera says, when they want something or when they’re in a particular bind. “When you’re talking about the Lord, it’s your creator. Everything. Your lord. Your master. Your owner. Your everything. I do believe that if you call God our Lord, it means he rules over you. And sometimes we don’t let him do that. We don’t let that happen. We call him Lord, yes, but on circumstance. Not on everything. And how come if he’s our Lord, we don’t allow him to rule over everything?” The question is rhetorical. “Sometimes, we want to take charge, and that’s when everything goes wrong. I can tell you. When you think, Oh, I have it. I’m in control. Guess what? You are not.”

“God allows me to perform without putting too much stress on myself,” says Rivera’s teammate and fellow Christian Andy Pettitte. For Rivera, more crucially, his faith in a perfect, ordered universe permits him to fail. Jorge Posada, the former Yankee catcher who is one of Rivera’s closest friends, believes that Rivera’s mental agility in the face of disappointment is the best evidence of the strength of his faith—better than the tattered Bible he carries with him always or the Bible verse (Philippians 4:13: “I can do all things through Christ who strengthens me”) the folks at Nike have embroidered discreetly on his cleats (so discreetly that even up close I have to strain to see it). “People have to fail, and through his faith he’s able to do that a lot better than most,” Posada told me. “It’s so hard in the game of baseball, you are failing a lot. He’s a freak of nature. He’s able to put his failures behind him so quick.” Posada is thinking of two spectacular failures in particular, when Rivera lost the lead in the fourth game of the 1997 division series against the Indians and blew the seventh game of the 2001 World Series against the Arizona Diamondbacks. “I asked him, ‘How did you bounce back from ’97, how did you bounce back from 2001?’ ” Posada marveled. “I can’t do that. I still think about the mistakes we do in life.”

Rivera loves the Gospel, but when it comes to baseball, he takes an Old Testament view. If winning is an honor to God, then perhaps creating a paralyzing fear in opponents is an even greater one. In the Yankee dugout, I ask Rivera what part of the Bible he likes the best. He answers immediately: He relates to the Hebrew Bible’s King David, the poor shepherd boy who saved his people by throwing a rock at the head of a monster. He was, Rivera says in his quiet, Spanish-inflected voice, “a killer.” David grew up into the rich and powerful King of Israel, a man who was a lover, a poet, and a warrior, who pleased God, the Bible says, even as he failed to live up to his commandments. “This was a man, yes, who made a lot of mistakes, but he always knew who his source was,” Rivera tells me. David fell in love with Bathsheba as he spied her bathing and then, wanting her, sent her husband, Uriah, into battle, knowing he would meet his death. The illicit union produced a son, and God expressed his disapproval by making that baby sick. When the baby was ailing, the great king wept and fasted. But when he died, David stopped grieving, to the surprise of his servants, got up, and went back to work. “The baby dies,” Rivera says. And King David? “Wakes up. Wash it off. Shave. Eat. Get ready. And move forward. Never look back. Never ask once again.”

I ask Rivera how it felt to lose the 2001 series, and he answers that God was in charge that day as he is on all others. “I did my best. I did everything within my power. I did everything within my power to win that game for us. Guess what? Didn’t happen. And you think I’m going to start like a child, Oh oh oh, I be crying? No, I did my best. My best wasn’t enough that day. I looked my boss into his eyes, and I said, ‘Boss, I did my best and my best wasn’t enough today.’ I can sleep comfortable and move forward.”

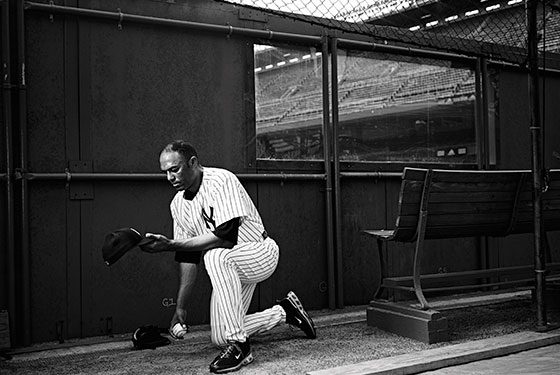

From his spot in the shade, Rivera contemplated the ancient story of David as he gazed upon the field, where his teammates were beginning batting practice. He had to go to work—bosses matter to him, as do punctuality and politeness.

There are those who feel that America’s pastime is like a religion, its parks, cathedrals, and its players like actors in a Passion play. “I don’t think that way,” Rivera says. “You get paid to play this game, and you have to produce, otherwise you won’t get paid. So it is a job.” When asked about his impending retirement, a crisis point in the life of any pro athlete, he says, “I can’t wait.”

When the season ends, after what he hopes will be his sixth World Series win, Rivera will devote himself to working in an actual church—his church, the wreck of a long-ago Presbyterian congregation purchased from the City of New Rochelle in 2011 and renovated, he says, at a cost of $2.5 million. It doesn’t look like much now—a stone shell with a shingled roof surrounded by heaps of dirt—but Rivera says it will be open for business in a month or two. New stained-glass windows were recently installed, he says, and inside the sanctuary, “that church is glowing, a kind of yellow-goldish color because the sun hits the stained glass and it looks, oh my God, fantastic.” The church is named Refugio de Esperanza, or Refuge of Hope. Clara, Rivera’s wife, will be its pastor. She is not yet ordained, but then that is not so unusual for a church like this one.

The Riveras already have a Christian-Pentecostal congregation waiting in the wings, a group of several dozen people who have been worshipping weekly at their home in Purchase for years, an organic outgrowth of an informal Bible study they started with a few other couples. “My house is kind of small,” he explains. “We only fit like 50 people, 60 people tops. Forty, average. We have whites, we have blacks, we have Hispanics. We’ll have all kinds. It don’t matter. As long as you love Christ, we in it. And if you don’t love him, we will work with you so we put you on the right path.” During the season, Rivera often worships in a Sunday-morning “Baseball Chapel,” led in the clubhouse by pastor George McGovern, but he comes to Clara’s services when he can, according to friends, sitting in the back row with his hand in the air, tears streaming down his cheeks.

But when Rivera says “church,” as in “My plan after baseball is to focus on church,” he means something much bigger than a new space to pray in. What he has in mind is a brotherhood (and sisterhood) of Christ, a spiritual and material outreach without boundaries, giving help to whoever needs it wherever they are, in the form of school supplies, haircuts, hot meals, Thanksgiving turkeys, toys at Christmas, college scholarships, bed sheets and bath soap for Sandy victims, and on and on. (The Mariano Rivera Foundation already donates between $500,000 and a million dollars each year.) He wants to keep funding church start-ups, as he’s already done in Mexico, the Dominican Republic, California, and Florida, not to mention New York. “In Panama, we have done I don’t know how many,” he says. Here, he wants to buy the building next to the church in New Rochelle and make it into an after-school program for at-risk kids. He and Clara are even talking about starting a seminary. Refuge of Hope, then, is more than a bricks-and-mortar retirement hobby; it’s a dream of a network of congregations and charities and pastors of the kind that used to be called, quaintly, a denomination.

This is not as outlandish as it sounds. Rivera is part of a huge, transnational religious movement, in which Latinos are turning away from religion in its institutionalized, hierarchical forms, especially Catholicism, and embracing the more intimate, do-it-yourself Pentecostal church. Like the vibrant tent revivals of the nineteenth-century American frontier, this is a grassroots phenomenon, fueled by transient populations of migrant workers, who are seeking a more emotional and immediate connection with God than what’s on offer in more established congregations. House churches like the Riveras’ are commonplace, and so are women pastors. Pentecostalism puts its focus on the Holy Spirit, the part of the Trinity that dwells within people and acts like an inner guide; it’s an emotional faith. At a typical Hispanic Pentecostal church you won’t see congregants passively listening to a minister sermonize, and you probably won’t see the lyrics to a hymn printed on a drop-down video screen. You’ll see lots of people underlining in their Bibles, and when they sing, they’ll be on their feet, praying with their whole body. Pentecostals tend to believe in healing, visions, and miracles, and some describe being baptized by the Holy Spirit, known as “speaking in tongues,” which looks to an outsider like nothing more than a protracted orgasm, with keening and babbling and uncontrolled shuddering or twitching. “I haven’t been baptized with the Holy Spirit,” Rivera says. “But I have seen it, and it’s beautiful. That’s what I want.”

Rivera hears the spirit talking to him “all the time,” he says—in dreams, in songs, and through the Bible. He also hears the spirit in prayer. When he reaches the mound, he always turns his back to the catcher for a minute and gazes down at the ball in his hand, and at that moment, he’s praying “that God watch not only me but my teammates. That no one get hurt,” he says. “The key is your heart,” Rivera says. “God don’t hear words.” Here he brings his hands up near his ears and, with his famous long fingers, makes jabbering mouth motions. “He goes direct to your heart and sees what is there.”

At one of our meetings, as sports reporters milled about the Yankees dugout, we found ourselves discussing Saint Augustine’s Confessions—the testimonial, written around 400 A.D., of a wayward young man who, weeping under a fig tree, hears a voice commanding him to read the Bible, a moment that changes him forever. “Saint. Saint,” Rivera repeated. “What is that?” Rivera was pretending not to understand: He has a reformer’s disdain for Catholicism’s hierarchical embellishments, including its catalogue of saints, which, he says, encourages men to worship other men. “When I read the Bible, I read that the Lord is jealous. He’s alone.” But when Augustine wrote his Confessions, I say, the Catholic Church was the only game in town. No, Rivera says. There was a church before that: the church of Jesus.

Like many Evangelicals, Rivera knows the Bible backward and forward, but he doesn’t use it like a hammer. His presence in the clubhouse is light and teasing—protective of younger pitchers, flirtatious with older women, warm with the numerous Yankees serfs who hang around waiting to fetch water and pack bags—and he sees it as his job to guide others, not to force them. “He’s not one of those people,” says Posada, who is Catholic. “If you sit down with Mariano for a long time, you’re going to hear a lot of quotes and a lot of things that the Bible says, but he doesn’t preach.” He does, however, believe the Bible is the Word of God, which makes him inflexible on certain matters. According to the second Book of Samuel, David had a best friend, a soul mate, whose name was Jonathan and whose love he treasured “passing the love of women.” Did you know, I asked Rivera during our first interview in the dugout, that some modern scholars argue that David and Jonathan may have been lovers?

“Lovers, meaning, lovers what?” he asked.

“Sexually,” I said.

Rivera threw his head back and laughed. Well, he said, the Bible doesn’t say that. Men can love each other, he said, looking out at his teammates on the field, and even lay down their lives for each other, without it being a sexual thing. On the question of homosexuality in sports, he gave a politician’s answer, accommodationist-sounding but firm in its conviction. “You want to be that, hey, you be it. If that’s going to make you happy, you be it. I do respect that. But I don’t share it,” he said. “If it’s the right thing to do—the Bible doesn’t tell me that.”

The next day, the locker room was dim and quiet, and I found Rivera sitting on a folding chair, tying his shoes. From behind, he looked like a movie still: the shaved head, the lanky frame, the No. 42 emblazoned on his back. When he turned around, he gave me his famous high-school-boyfriend smile, shook my hand, then ran off somewhere. I dawdled around his locker and wondered what it must be like, for a man like him, in a locker room like this, full of egotists and sinners, some of whom likely tolerate his saintliness and the adulation of the press only because of his extraordinary human ability. About steroids, Rivera says, “God has given you everything you need. ”

Rivera believes, along with most conservative Evangelicals, that the only way to Heaven is through Jesus. But what about the Jews, the atheists, the hedonist rookie, the lapsed journeyman, and the agnostic reporters who worship Rivera but not his God? Within minutes, Rivera unexpectedly came bouncing back and I ask: Would a loving God really condemn good people for not believing in him?

God doesn’t accept excuses, he says. “Someway, sometime, you’ve heard about Jesus. Even if you live in China, you would have heard. The Bible says we’re all going to be judged.” About his teammates in particular, Rivera says, “Christ came for the sinners, not for the saved. You don’t go to the doctor if you’re healthy.”

Every converted Christian has a once-was-lost-now-am-found narrative, and Rivera is no exception. Most stories about his early years draw on a kind of romanticized poverty, in which he learns from his father working on a fishing boat about respect and determination and in his spare time plays baseball, using a mitt improvised from a milk carton (in one version I heard, from a minor-league friend, it was the crushed cardboard from a case of beer). In truth, back then, Rivera loved soccer much more than baseball and when asked recently could not name a single major-league pitcher from his boyhood.

Rivera hints at a dark period during his late teenage years, about which he will say very little: “I was doing the wrong things. It was just bad. If I kept going that way, I would have been dead,” he says. “The crowd I was hanging with wasn’t the right crowd. And with that, I’ll leave it like that.” It was around that time his cousin Vidal introduced him to the idea of an unmediated faith, which spoke to him in a way his childhood Catholicism had not. “He started talking about Christ and relationship and what he did for us on the Cross, and I said, ‘Wow.’ I was intrigued. I started reading the Bible and searching and find out who Christ was and is.”

When he was 20, the Yankees signed Rivera for $3,000, and he commenced the vagabond life of a minor-league player, living in Tampa, Greensboro, and Columbus over the next five years and traveling home to Panama in the winter to see his family and Clara, whom he knew from childhood and married in 1991. In those years, Rivera may have had his distractions, but to those around him, he seemed already completely focused on getting to the major leagues. Wherever Rivera sat on the bus was the quiet section, remembered his occasional roommate in the minors, Ron Frazier, and when the other guys went out after games to drink and play pool and chase girls, Rivera stayed in and got his rest. “I was one of those guys who drank beer and played pool,” says Frazier, now a high-school teacher on Long Island. “He would talk to me. He would say, ‘You got to keep your priorities straight.’ I just knew then and there he had it right.”

Nothing about Rivera’s major-league start, however, portended his awesome career. He had an operation on his elbow in 1992, and a full recovery was uncertain. And even though his fastball gained tremendous velocity in 1995, reaching around 95 miles an hour, he was far from a sure thing. He was called up that spring, when he was already 25 years old, an age at which many pitchers are beginning a decline they can only forestall with pitcherly savvy. “Another shabby outing by another young pitcher,” wrote Jack Curry in the New York Times in June. Even Rivera’s voice comes down through the decades as wavering, the sound of a rookie trying to act brave. “When I got in there, I had to be in control. I tried to be in control,” he told reporters in September after facing off against the A’s. Today, Rivera has disdain for the word trying, a verb he thinks indicates a less-than-total commitment. During one of our conversations, I was fiddling with my voice recorder and apologized for making him wait. “Don’t say, ‘Sorry, sorry,’ ” he told me, teasing. “Just get it done.”

In 1996, he earned a permanent spot in the Yankees bullpen, and the team won the World Series; by the next year, he was working full time as their closer. But off the field, life was a work-in-progress. He still had not given himself to God. “The commitment level as a younger man sometimes is a little bit different, a little bit difficult,” says Pettitte, who was Rivera’s peer in the minors and has watched his faith mature. “Sometimes you’re a little more distracted and not as focused on what you want your walk to be.” And maintaining a long-distance relationship with his wife and children (the oldest of three sons, Mariano Jr., was born in 1994) was tough on the family. While he played in the minors—and for his first several years in the majors—Rivera thought of himself as “living” in Panama with a job that took him frequently out of town, almost like the migrant workers who share his faith. For Clara, coming from a close-knit Panamanian family, Westchester, and the world of professional baseball, was an entirely alien universe. “I won’t say she was lonely,” Rivera says. “But we didn’t have no one here. No one.”

One day, soon after Rivera’s debut, from their apartment in New Rochelle, Clara reached out to a woman she’d heard about through relatives, a leader in a Pentecostal denomination called the Church of God of Prophecy. This woman and her husband became Clara’s American support system, and soon Mariano’s as well—they prayed together, read the Bible, and even helped the Riveras set up their house. Rivera calls them “his spiritual parents”; the wife he calls “Mami.” It was Mami who eventually brought Mariano to God. “It was personal. Beautiful,” Rivera says. Today, whenever the Riveras go on vacation, they do so with 40-odd people, including parents both biological and spiritual. “I’m always with my family,” Rivera says. “Where I go, my family goes.”

We are sitting together during our final meeting, once again huddled in the Yankee dugout. I had come to see these conversations as a kind of Bible study, but this time, he seemed distracted. It was nearly a hundred degrees in the sun, and the season had settled into the long, hot stretch when opening day is long behind you and the playoffs are still more than a hundred games away. “I’m tired,” he said as he scooched up next to me on the bench, then inched rightward to get a better view of the opposition while they took their practice swings.

When I ask him what brought him to God, he says that, like everyone, he’s vulnerable to temptation. “When we’re still alive, when we’re still breathing, we will go through temptations,” he told me. “The thing is how we’re going to get through it. Again, we all fail. We all fall short.” But his view of his own born-again experience isn’t transactional: A person gives himself to God because he understands at his deepest core that he needs salvation. “Lord, here I am” is how he describes the moment. “I’m a sinner. I’m a sinner. Guess what. I’m surrendered to you. I don’t want to do it no more—whatever I’m doing that doesn’t please you, take it away from me. I surrender to you. Come, dwell in me.”

Rivera found his cutter shortly after being born again, and this, he says, is no coincidence. The story has been told before, but it bears repeating here. In the spring of 1997, Rivera was a conventional fastball pitcher, hurling heat straight at the plate and mixing that up with breaking and off-speed pitches. But during pitching practice one day, he suddenly found that he could not make his fastball stay on course. He had been having a tough spring, he says, thinking too much and feeling pressure to always be perfect. And here was this ball, out of nowhere, seemingly with a life of its own, and Rivera completely unable to control it. The bullpen catcher thought he was messing around, and the mystified pitching coach worked with Rivera for weeks, trying to help him get the ball to settle down. But he couldn’t. Or it wouldn’t. And so finally, according to Sports Illustrated, Rivera said, “I’m tired of working at this, let’s let it happen.” To me, he said only this: “In God is purposes.”

As part of his farewell tour, Rivera has been visiting with small groups of people connected with opposing ball clubs on the road—thanking hot-dog vendors and the group-sales guy for working hard. I saw him do this at Citi Field, on Memorial Day, before the first game of the Yankees’ series against the Mets. “It’s an honor and a privilege,” he began.

For seventeen years, Rivera has been perhaps baseball’s humblest hero, always thanking God in an understated way. He’s not in the news for beating up his model girlfriend or falling out with his agent—in fact, he’s hardly in the news at all. He doesn’t bad-mouth the people who write him checks. He has off days, but never slumps.

And now, in this victory lap, his discomfort with the spotlight shows. It is easier for him to be history’s greatest closer than it is for him to reveal himself, because he sees that making a display of his humility puts that all-important humility in doubt. Having lived in New York for nearly twenty years, he knows, on some level, that the fans, and even his teammates, are drawn more to his superstardom than they are to his innermost thoughts; the beliefs are of interest only because he’s so great. “I don’t want people to think that I do [church work] because I want attention,” he told me. “I don’t ever want that. I do it because it comes from my heart and not for the publicity.”

At Citi Field that day, the event had a staged feeling; it was heartfelt but also for show. The Mets returned the honor the following evening, asking him to throw out the first pitch—an exceptional, gracious gesture for an active pitcher on an opposing team. Later that night, he entered the game to pitch for real, with the Yankees ahead 1-0 in the ninth. The lowly Mets struck quickly, getting three consecutive hits off Rivera and stealing the game. It was the worst outing of Rivera’s career. And it was humbling. It may have been part of God’s plan, but with reporters later that night, the pitcher took full responsibility.